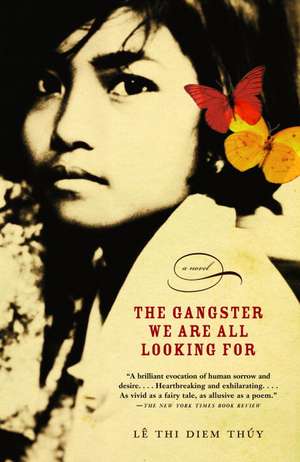

The Gangster We Are All Looking for

Autor Thi Diem Thuy Le THUY LEen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2004

In 1978 six refugees—a girl, her father, and four “uncles”—are pulled from the sea to begin a new life in San Diego. In the child’s imagination, the world is transmuted into an unearthly realm: she sees everything intensely, hears the distress calls of inanimate objects, and waits for her mother to join her. But life loses none of its strangeness when the family is reunited. As the girl grows, her matter-of-fact innocence eddies increasingly around opaque and ghostly traumas: the cataclysm that engulfed her homeland, the memory of a brother who drowned and, most inescapable, her father’s hopeless rage.

Preț: 88.04 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.85€ • 17.59$ • 13.91£

16.85€ • 17.59$ • 13.91£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375700026

ISBN-10: 0375700021

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 126 x 209 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0375700021

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 126 x 209 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

lê thi diem thúy [pronounced LAY TEE YIM TWEE] was born in Vietnam and now lives in western Massachusetts.

Extras

suh-top!

Linda Vista, with its rows of yellow houses, is where we eventually washed to shore. Before Linda Vista, we lived in the Green Apartment on Thirtieth and Adams, in Normal Heights. Before the Green Apartment, we lived in the Red Apartment on Forty-ninth and Orange, in East San Diego. Before the Red Apartment we weren’t a family like we are a family now. We were in separate places, waiting for each other. Ma was standing on a beach in Vietnam while Ba and I were in California with four men who had escaped with us on the same boat.

Ba and I were connected to the four uncles, not by blood but by water. The six of us had stepped into the South China Sea together. Along with other people from our village, we floated across the sea, first in the hold of the fishing boat, and then in the hold of a U.S. Navy ship. At the refugee camp in Singapore, we slept on beds side by side and when our papers were processed and stamped, we packed our few possessions and left the camp together. We entered the revolving doors of airports and boarded plane after plane. We were lifted high over the Pacific Ocean. Holding on to one another, we moved through clouds, ghost vapors, time zones. On the other side, we walked through a light rain and climbed into a car together. We were carried through unfamiliar brightly lit streets, and delivered to the sidewalk in front of a darkened house whose door we entered, after climbing five uneven steps together in what had become pouring rain.

In 1978, an elderly couple in San Diego decided to sponsor, through their church group, five young Vietnamese men and one six-year-old girl from a refugee camp in Singapore. Mr. Russell was a retired Navy man. He had once been stationed in the Pacific and remembered the people there as being small and kind. When Mr. Russell heard about the Vietnamese boat people, he spent many sleepless nights staring at the ceiling and thinking about the nameless, faceless bodies lying in small boats, floating on the open water. In Mr. Russell’s mind, the Vietnamese boat people merged with his memories of the Okinawans and the Samoans and even the Hawaiians.

One night, Mr. Russell fell asleep and dreamed that the boats were seabirds sitting on the waves. He saw a hand scoop the birds up from the water. It was not his hand and it was not the hand of God.

The birds went flying in all directions across the blinding blue sky of Mr. Russell’s dream, but finally he saw them fly in only one direction and that was toward the point where in the dream he understood himself to be waiting, somewhere beyond the frame.

The original plan was that my father, the four uncles and I would live with the elderly couple, but as our papers were being processed Mr. Russell died and there was some question as to where we would be sent. Tokyo? Sydney? Minneapolis?

Mr. Russell had told Mrs. Russell his dream about the birds. After his death, she considered the dream and decided that we should move in with their son, Melvin.

Ba said it was no one’s fault that we lasted only one season at Mel’s place.

When Mel approached us at the airport, we heard a faint rattling: a ring full of gold and silver keys hang- ing from his belt. With each step Mel took, the ring swung and rattled by his side. The keys were new to him. Mel was tall and thin, but the ring looked fat, important. Mel caught the ring and pushed it into his pocket. This silenced the keys for a moment. He shook everyone’s hand—including mine—and laughing nervously said, “Welcome to America.”

He then waved his hand in the air and when I followed it with my eyes, I saw a poster of a man and a woman at the beach, lying on striped towels, sunning themselves between two tall palm trees. Above the palm trees were large block letters that looked like they were on fire: SUNNY SAN DIEGO. The man was lying on his stomach, his face buried in his folded arms. The woman was lying on her back, with one leg down and the other leg up, bent at the knee. I looked through the triangle formed by the woman’s tanned knee, calf and thigh and saw the calm, sleeping waves of the ocean. My mother was out there somewhere. My father had said so.

After Mel and his mother took us to the room in Mel’s house where Ba, the four uncles and I would all be sleeping, they wished us goodnight and left us alone, closing the door quietly behind them. They stood in the hallway and we could hear them talking. Even without understanding a word of what they were saying, the tone of their voices troubled us. Had we been able to understand, we might have heard the following:

“I feel like I’ve inherited a boatload of people. I mean, I’ve been living here alone and now I’ve got five men I’ve never met before, and what about that little girl?”

“Dear, you know your father wanted them here.”

“Here in America, sure, but not here with me.”

“Well, it’s worked out that way. If your father were here—”

The woman started to cry.

“I’m sorry, Mother. I’m so sorry.”

We heard their footsteps move down the hallway toward the living room.

Inside the bedroom, we all remained quiet in our places. Ba was standing with his back against the door. The four men were sitting on the two bunk beds and I was sitting on the double bed, my knees pulled up near my chest.

One of the uncles took a deep breath and lay down on the bed. He was still wearing his shoes and let his feet hang off the edge of the bed so he wouldn’t get the covers dirty.

Ba stepped forward and explained to the four men and me that Mel had bought our way into the United States. He said that Mel was a good man. We heard without really listening. We nodded. Ba said that Mel had let the people at the airport gates know that it was O.K. for us to be here. “If it wasn’t for him,” Ba said, “they would have sent us back the way we came.”

We each thought of those long nights floating on the ocean, rocking back and forth in the middle of nowhere with nothing in sight. We remembered the ships that kept their distance. We remembered the people leaning over the decks of the ships to study us through their binoculars and not liking what they saw, turning away from our boat. If it was true that this man Mel could keep us from floating back there—to those salt-filled nights—what could we do but thank him. And then thank him again. Only why did it seem from the tones of the voices in the hallway as if something was wrong?

Ba said that we had to be patient.

Two of the uncles nodded. One closed his eyes. One lay down and turned toward the wall. I wrapped my arms around my knees and studied my bare feet. They were very clean; not a speck of sand or salt on them.

Ba said whatever we might come to think of Mel, we should always remember that he opened a door for us and that this was an important thing to remember.

There were things about us Mel never knew or remembered. He didn’t remember that we hadn’t come running through the door he opened but, rather, had walked, keeping close together and moving very slowly, as people often do when they have no idea what they’re walking toward or what they’re walking from. And he never knew that during our first night in America, as he and his mother sat on the living room couch holding on to each other and crying because Mr. Russell was gone, Ba had climbed out the bedroom window and was sitting in the shadow of the palm trees on the front lawn of the house, staring at the moon like a lost dog, and also crying.

. . .

The ring of gold and silver keys that rattled beside Mel opened the doors to condominiums, duplexes, and town houses in various states of neglect. Mel was not good with tools and, since a bicycle accident in early childhood, was generally rather fearful, a fact that had always pained him, especially around his father. In exchange for letting us live with him—an arrangement he reluctantly agreed to, to satisfy what his mother called his father’s “dying wish”—Mel employed Ba and the four uncles as his crew of house painters and general maintenance men. He was relieved not to have to climb shaky ladders or crawl through dark, narrow spaces to see about small broken things.

When the white walls in one of his properties had faded or become dirty with the grubby prints of people’s lives rubbing up against them, he sent Ba and the four uncles in with directions to “touch them up,” “make like new,” “make white again.”

On almost every day of the week, you could find them working: five small-boned Vietnamese men climbing ladders in empty rooms, painting the white walls whiter.

“So much white is unlucky.”

“Layers of white bury you.”

“In between the first coat and the third—”

“Death could slip in and—”

“Press you up against the wall and—”

“Wrap you up in coats of white.”

“Dressing you for your own funeral.”

. . .

Of all the men, Ba knew the most English; he had picked some up from the Americans during the war. The uncles asked Ba to ask Mel why the walls had to be so white. Ba didn’t know the word “so.” His question came out like this:

“Why white?”

Mel said, “It’s clean.”

That was the end of the conversation.

When Ba told the uncles what Mel had said, they stared at him blankly.

“No,” they said, turning to the white walls. “We don’t understand.”

They picked up their paintbrushes and rollers and rags and went back to work.

Ba tried to tell them again, the way Mel had told him, in that voice that shines bright in your face like a flashlight aimed at your eyes when you’re sleeping. It’s a voice that doesn’t explain, though it often says things in tones that make you wonder. My Ba does not have such a voice. Ba’s voice echoes from deep down like a frog singing at the bottom of a well. His voice is water moving through a reed pipe in the middle of a sad tune. And the sad voice is always asking and answering itself. It calls out and then comes running in. It is the tide of my Ba’s mind. When I listen to it, I can see boats floating around in his head. Boats full of people trying to get somewhere.

. . .

Mel had stopped going to church years ago but after his father’s death, he started going again. Every Sunday morning he would drive to his parents’ house to pick up his mother and accompany her to church. During our first month at Mel’s, Ba and the four uncles and I would all pile into the car and go with them. But after a couple of Sundays in a row during which the uncles either slept through the sermon or stared at the floor absentmindedly, picking dried paint off their hands and fingernails, it was decided that we should stay at the house while Mel and his mother went to church.

After church, Mel would bring his mother by to visit with us.

We would all gather around the coffee table in the living room, Mel seated on the lounge chair in the corner, reading the Sunday paper, Ba, the four uncles and I taking turns smiling at Mrs. Russell, who sat on the couch and smiled patiently back at us.

“Now, what’s happening in the world?” she’d ask Mel.

“Oh, the usual,” he’d answer.

Mrs. Russell’s face was always made up, and when I leaned in reluctantly to kiss her, it smelled of sweet powder and rouge. She wore necklaces and earrings with bright purple and red stones. Some of the earrings were in the shape of flowers and some hung like clusters of lights shining from either side of her face.

From that house of bachelors, Mrs. Russell chose my Ba and me as her favorites. Perhaps she sensed we’d once had a woman in our lives. She bought me pastel-colored dresses to wear to school and smaller versions of those necklaces and earrings she liked to wear. The jewelry came cushioned on cotton squares inside little white boxes that rattled hollow when she shook them.

On Sunday afternoons that first winter, she would take my Ba and me for long drives up into the mountains. After the telephone wires and the streets of the city had slowly given way to treetops and gravel roads, we would get out of the car and find ourselves surrounded by snow. A small woods stood before us, and the road fell away in the distance behind us. There was nothing up there but snow and sky. And it seemed that all we ever did was walk in circles, making footprints in the soft snow.

After the third trip to the mountain, I asked Ba why Mel’s mother was always taking us up to the snow.

He said, “Maybe she thinks we think it’s magic, the way she can take us to a snowy place that’s so near a hot city.”

“Why doesn’t she take us to the beach?” I asked.

Ba shook his head. “No. Not possible. There’s no reason for us to go there.”

“But Ma’s there,” I said.

“No, she’s not,” Ba said, leaning down to zip up my jacket.

“You told me she was at the beach,” I said.

“Not the beach here. The beach in Vietnam,” Ba said.

What was the difference?

The grandmother brought a small camera with her on these trips. She liked looking at things through it. On our very first trip to the mountain, she took a photograph of Ba and me standing in front of Mel’s blue car.

In the photograph, Ba is wearing brown pants and a turquoise velour sweatshirt. His hair is parted on the side and pushed back behind one ear. I am wearing blue jeans and a yellow-and-red striped sweater that you can’t see because it’s under the ivory-colored sweater the grandmother had pulled from the trunk of the car, shaking the dust off before helping me into it. Before we took this picture Ba brushed my bangs across my forehead so they wouldn’t fall in my eyes.

In this photograph, my Ba and I hold hands and lean against the blue car. We are looking at the camera, waiting for that flash that lets us know something has happened inside the body of the camera, something that makes it remember us, remember our faces, remember our clothes, remember the blurred shape of our hands captured in that second when we shivered, waiting.

After the grandmother took this picture, she led us toward the woods.

. . .

That first day on the mountain, I made a game of following in my Ba’s footsteps so I left no tracks of my own in the snow. When I stopped and looked back in the direction we had come from, I could see only my Ba’s footprints and the grandmother’s. The footprints began at the car, which looked, from a distance, like a shining blue box that had dropped from the sky.

I watched Ba walking slowly toward the woods. He had his hands behind his back and was staring at the ground. The grandmother walked ahead of him. She was looking through her camera at the sky, at the tops of trees and, sometimes, back at us.

I ran after them.

In the thickest part of the woods, she stopped walking and turned to face us. She was smiling and I remember how her head shook slightly, sending the shiny balls on her earlobes swinging like searchlights.

She laid her palm against the trunk of a tree and with her finger traced some letters that had been carved there. She was smiling and crying at the same time.

I closed my eyes. When I opened them, Ba was squatting in the snow with his eyes closed and his hands to his ears the way I used to squat in the shadow of the fishing boats at home when we played hide-and-go-seek, my eyes shut tight so no one could see me. I ran over to Ba and threw my arms around his neck and climbed onto his back.

“Where’s my Ba?” I asked, pretending he was a big rock. “I wonder where my Ba is hiding in all this snow.”

The big rock stood up and became a tree. The tree tried to shake off all the snow that had gathered on its branches. I held on tightly and the tree became a wild horse whose neck I clung to as it went running across the fields. The horse ran and ran and ran. And as it ran, it asked itself, “I wonder where my little girl has disappeared to.”

I put my hands in front of my Ba’s eyes and wiggled my fingers like ten squirming fish out of water. I said, “Ba! Ba! Here I am! I’m right here!”

We galloped out of the woods, stamping designs into the snow. We shouted each other’s names and let them echo all around. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the woods getting smaller. When Ba stopped running to catch his breath, I heard the light crunching of the grandmother’s steps, somewhere far behind us.

Ba and I envied the four uncles. They were never invited to come with us on the mountain drives. They spent their Sunday afternoons walking around the neighborhood, looking for signs of other Vietnamese people. It took them a while but they finally found some other Vietnamese men at a pool hall. Every Sunday after that, they would return to the pool hall.

While Ba and I were following the grandmother around in the snow, the uncles were smoking cigarettes, drink- ing iced coffee, shooting pool and learning to watch and then bet on football games with their new Vietnamese brothers. They had such a good time they wouldn’t come home until late on Sunday nights. Ba and I would wake up early on Monday mornings and find the uncles asleep on their bunk beds.

Often they would still have their coats on and one uncle, sleeping on a top bunk, never managed to kick off both his shoes. Ba would lift me up and I would wiggle the shoe from side to side until I could pull it off the uncle’s foot. Then I would fish under the bed for the shoe that had been kicked off the night before. I would pair the shoes and leave them in the middle of the room, with their toes pointing toward the door.

Weekday mornings, after I’d brushed my teeth and washed my face, Ba would hand me one of the pastel-colored dresses the grandmother had given me. I’d pull the itchy, rustling dress over my head and let it hang for a moment around my neck, a huge flower whose petals were bunched and whose center had been replaced by my frowning face.

“I don’t want to wear American dresses,” I’d say to Ba.

Ba lowered the edges of his mouth and raised his eyebrows at the same time, like a clown about to cry. He shrugged his shoulders at me and reached under the bed for my school shoes, a pair of clear plastic sandals—also from the grandmother—that let the playground pebbles get stuck between my toes every time I kicked at the dirt.

I’d run around the room and let the dress rise up and down around my neck, like rooster feathers ruffling before a cockfight.

“Who wants to wear American dresses? Who?” Running in small circles I’d chant a litany of “Who? Who? Who?”

Ba would sometimes join me by standing on one leg and kicking back with the other, with his hands cupped under his armpits and his elbows jutting out like wings. Tilting his head to one side, he’d furrow his brow and chant, “Who? Who? Who?”

“Who’s there?” one of the uncles would ask, in a sleepy voice.

I’d run out of the room pulling the dress on in the hallway. From inside the room, I could hear Ba’s voice, reassuring. “It was only the girl, dancing.”

“Cooing like a common pigeon,” another of the uncles would complain.

“Every morning that girl runs around like a headless chicken,” said another.

“Isn’t she late for school?” asked yet another.

I’d stand in the hallway, leaning casually against the wall, my legs crossed at the ankles. After a minute, Ba would come out of the room, quietly closing the door behind him. He’d hand me my plastic sandals. I’d sit down on the floor of the hallway and slip them on. As I tightened the buckles, I could hear the uncles rolling around in their beds, groaning, trying to find the comfortable spot they’d lost upon waking.

Ba and I would tiptoe to the front door. Mel often slept until noon, so we all had to be quiet when leaving the house.

We’d stand on the sidewalk and Ba would comb my hair with his fingers. Then he’d pull two barrettes out of his shirt pocket, push my hair away from my eyes, and gently snap the barrettes in place.

As we walked toward the school, he’d often tell me not to make so much noise in the morning.

Once, he told me Mel had complained to him that he could hear me “chattering in his sleep.” When Ba told me that, I said, “Dumb birds chatter. I don’t chatter.” Ba squeezed my hand and didn’t say anything.

A block away from my school, Ba and I would stop at a red-and-white sign on the street corner and I’d put my arm around the post. We did this every morning. Ba would stand beside me and wait while I then wrapped one leg around the post and hung my head as far as it would go to one side.

I liked looking at things from this angle. Everything was upside down. I would look at the long gray chain-link fence that surrounded my school playground. I imagined how all the children standing with their feet pressed firmly against the ground, and their heads pointing toward the top of the chain-link fence, would slowly slip into the pale blue sky. I imagined the children floating, their dresses ballooning out around them as the wind ruffled their hair across their faces. I’d look over at Ba, also upside down, and I would imagine him floating too, with his hands folded across his chest.

While the blood was rushing to my head, Ba was studying the letters on the sign. He practiced reading the word. He would slowly part his lips and then close them, making this sound: “Suh-top!” “Suh-top!” “Suh-top!”

I was the only Vietnamese student at my school. On the first day of class, the teacher introduced me to the other students by holding a globe in one hand as she gave it a spin with the other, and then pointing with her finger at an S-shaped curve near a body of water.

Was that where I had come from?

As I stood before them in a dress the color of an Easter egg, with my feet encased in clear plastic sandals, the other students looked at the globe and then back at me again. Some whispered behind their hands. Some just stared. I imagined the stripes on my underwear flashing on and off, like traffic signals, under the dress.

At recess that first day of school, as I stood in the shadow of a big electrical box on the edge of the playground, I missed my older brother. Could he see me standing here? Was he wondering why I wasn’t playing with the other children? Wasn’t I exactly like our limp-footed schoolmaster in Vietnam? The one who used to stand in the doorway of the schoolhouse and watch his students run up and down the beach yelling,

“Hey! Who can run faster than me?”

“Who can jump higher than this?”

“Who can swim past the horizon and back before the end of recess?”

When the loud bell rang at the end of recess the students at my American school formed a line at the edge of the blacktop. In a line, my class walked into a big room with rows of plastic green mats on the floor. The mats were in groups of two or three, separated by shelves of children’s toys. Everyone lay down on a mat with eyes shut until we were given a signal to open our eyes again.

“Go to sleep now,” the teacher would say. “If you can’t sleep, close your eyes and try to rest. Close your eyes. That will help.”

Ever since my brother left, I’ve had a hard time taking naps. At school in America, I lay on the green mat and stared at the white ceiling. Sometimes I would see a blond baby doll lying beside me on the shelf of toys. I would entangle my fingers in her coarse hair and lie still, listening to the other students breathe. While the doll’s blue eyes were dutifully closed behind long brown lashes, I stared at the ceiling and studied the shapes I saw there: a chair, a tree trunk, the face of an old man, a sliver of moon.

I began to play with the ceiling, a game that I used to play with the sky when I was lying in the fishing boat on the sea. At that time, I thought that everyone and everything I missed was hovering behind the sky. The game involved looking for a seam to the sky, a thread I could pull. I told myself that if I could find the thread and focus on it hard enough with my eyes, I could tear the sky open and my mother, my brother, my grandfather, my flip-flops, my favorite shells, would all fall down to me.

Before I could find the thread that would split the ceiling wide open, a student wearing a cape and holding a silver stick with a shiny star at its tip would come around to wake us. The star-holder shuffled quietly among the sleeping bodies, touching the star to one after another. The sleeping students stirred and woke. But when the star-holder came to wake me, I always sat up before he could touch me. Once, I forgot that my fingers were still entangled in the doll’s hair. As I sat up, her body jerked forward with me, knocking the plastic fruit off the shelf. Apples and oranges bounced onto the floor. That day, the star-holder hurried past me.

“Shhhh!” My teacher said, pressing a long finger against her fish lips. “Shhhh!”

Over the years, Mr. and Mrs. Russell had collected small glass figures of animals, mainly horses. The animals had skinny glass legs you could see through, as through a clean window. After Mr. Russell’s death, Mrs. Russell decided that her son Melvin should have some of these glass animals, along with a number of other things that had once belonged to his father.

One Sunday afternoon Mel and his mother pulled up to the house and Mel called for Ba and the uncles to come out and help him. A glass display cabinet was wedged in the open trunk of Mel’s car. After directing a couple of the uncles to maneuver the cabinet carefully out of the trunk, Mel told Ba and the other uncles to get the three cardboard boxes sitting on the backseat and then he waved for everyone to follow him. With his mother holding the front door open, Mel led the uncles and Ba up the five uneven steps and into the house. They carried the cabinet and the three boxes down the long hallway and around to the back of the house, to a room that was Mel’s office. I followed behind them, my hands tucked in the back pockets of my jeans.

Mel’s office was a small and crowded room. Half-emptied boxes lay on the floor. Shelves bowing under the weight of books and files lined the walls, and in the cen- ter of the room was a large square desk, its top covered with pens, papers, receipt books, a tray of keys and spare change. Behind the desk was a leather swivel chair.

Mel directed the uncles to place the glass cabinet in the far corner of the room, so that while sitting at his desk, he could look up and see into the cabinet.

As we stood watching, Mel and his mother unpacked the contents of the three cardboard boxes and placed them carefully inside the glass cabinet. First we saw five pieces of blue-and-white china. Then came some red leather-bound books. Mel spun the wheels on a toy fire truck before placing it inside the cabinet. His mother unwrapped a pipe that still had tobacco in it and handed it to Mel. Mel lay the pipe down on its side gingerly. The last to come out were the glass animals. There were about twenty of them and they were lined up in pairs, like animals in a parade.

We were invited to look into the glass cabinet. As we stood peering in at the contents, the old woman told Mel to tell Ba to tell the four uncles and me that the things inside were not for touching.

Ba didn’t tell us anything; he just asked us, “Do you understand?” and the four uncles and I said, “Yes.” We had all sensed that the things in the cabinet were valuable, not because they looked valuable to us but because they had been separated from the disorder of the rest of the room and the rest of the house.

As we were leaving Mel’s office, I noticed a golden brown butterfly lying atop some papers on his desk. I reached to touch it. Instead of the powder that usually comes off of butterfly wings, my fingers brushed across cold glass. Pausing in the doorway, I glanced over my shoulder toward the desk. What was that?

. . .

At the beginning and the end of every school day, two older students stood in the middle of the street across from the school entrance; they carried signs they crossed like sabers in battle. This meant the cars—all of them, every one of them, even the big yellow buses—had to stop so the children could cross the street to go to school or cross the street to leave school and go home, wherever home might be.

Each afternoon I would run past the crossed signs to meet whichever uncle had come to walk me back to Mel’s house. As the uncle and I passed the red-and-white sign at which Ba and I paused every morning, I’d brush my fingers against the post and whisper, “Hi.”

The uncle would let me into the house and I would race down the hallway to our room and change out of the itchy dress into my jeans and a T-shirt. I usually had an hour alone before Ba or one of the other uncles would come home and start dinner.

At first I used to spend the hour coloring or studying the reading book with pictures of the boy, the girl, and their dog, Spot, who liked to chase after the bouncing ball. But after the day we had watched Mel fill his cabinet, I would sneak into Mel’s office and spend the hour visiting with the butterfly and the glass animals.

The butterfly was golden brown and I found it lying as before inside the thick glass disk atop the stack of letters and rent receipts on Mel’s desk. When I picked up the disk, I saw that the butterfly was trapped in a pool of yellow jelly. Though I turned the glass disk around and around, I could not find the place where the butterfly had flown in or where it could push its way out again.

I held the disk up to my ear and listened. At first all I heard was the sound of my own breathing, but then I heard a soft rustling, like wings brushing against a windowpane. The rustling was a whispered song. It was the butterfly’s way of speaking, and I thought I understood it.

I cupped the disk in my palms and, gazing down at the butterfly, carried it over to the window overlooking the back garden. When I held it up to the sunlight, the disk glowed a dazzling yellow and at the center of the yellow was the rich earthen brown shape of the butterfly.

I carried the disk back to the desk and put it back atop the stack of letters and rent receipts. It pressed down on the paper the same way my Ba’s heavy head pressed down on the pillow at night, full of thoughts that dragged him into nightmares when all he wanted was a dream as sweet and happy as the taste of jackfruit ice cream.

When Ba and I lay down to sleep one night, I whispered into Ba’s ear, “I found a butterfly that has a problem.”

“What is the problem?” Ba asked.

“The butterfly is alive . . .”

“Good,” Ba said.

“But it’s trapped.”

“Where?”

“Inside a glass disk.”

Ba said nothing.

“But it wants to get out.”

“How do you know?”

“Because it said this to me: ‘Shuh-shuh/shuh-shuh.’ ”

Ba sat up, shook his heavy head back and forth and tapped on the side of one ear, then the other.

“What are you doing?” I asked him.

“I must get these butterfly words out of my head before they grow bigger,” Ba said, tilting his head far to one side so the words could slip out like water.

“Ahhh . . .” he sighed, pulling on his earlobes, “empty of all butterflies. Now I can sleep.”

The next morning, I went out to where the uncles were working, in a corner of the back garden. They were trimming plants, pulling up weeds, refilling the bird feeder. When one of the uncles asked me why I looked so serious, I told him that I needed his help. All the uncles stopped what they were doing and wanted to know what was wrong.

I explained with my fingers arching and meeting in an imperfect circle that there was a butterfly trapped inside a glass disk, and that when you held the disk up to the light—my arms now reaching toward the sun—the butterfly lit up, golden brown.

I asked the uncles to help me get the butterfly out.

“Impossible!”

“That butterfly got itself into a lot of trouble flying into a disk.”

“It’s not trouble we can do much about, though.”

“Yeah, what do we know about butterflies stuck in glass. I never saw anything like it in Vietnam.”

“But doesn’t it sound terrible?” I asked.

“It must be dead now, that butterfly.”

“Can’t do much for a dead butterfly.”

“No, I heard it rustle its wings. It wants to get out!”

“Listen to me, little girl, no butterfly could stay alive inside a glass disk. Even if its body was alive, I’m sure that butterfly’s soul has long since flown away.”

“Yes, that’s how I think of it also. No soul in that glass disk.”

“If there’s no soul, how can the butterfly cry for help?” I asked.

“But what does crying mean in this country? Your Ba cries in the garden every night and nothing comes of it.”

“Just water for Mel’s lawn.”

“Nothing.”

They went back to work.

Linda Vista, with its rows of yellow houses, is where we eventually washed to shore. Before Linda Vista, we lived in the Green Apartment on Thirtieth and Adams, in Normal Heights. Before the Green Apartment, we lived in the Red Apartment on Forty-ninth and Orange, in East San Diego. Before the Red Apartment we weren’t a family like we are a family now. We were in separate places, waiting for each other. Ma was standing on a beach in Vietnam while Ba and I were in California with four men who had escaped with us on the same boat.

Ba and I were connected to the four uncles, not by blood but by water. The six of us had stepped into the South China Sea together. Along with other people from our village, we floated across the sea, first in the hold of the fishing boat, and then in the hold of a U.S. Navy ship. At the refugee camp in Singapore, we slept on beds side by side and when our papers were processed and stamped, we packed our few possessions and left the camp together. We entered the revolving doors of airports and boarded plane after plane. We were lifted high over the Pacific Ocean. Holding on to one another, we moved through clouds, ghost vapors, time zones. On the other side, we walked through a light rain and climbed into a car together. We were carried through unfamiliar brightly lit streets, and delivered to the sidewalk in front of a darkened house whose door we entered, after climbing five uneven steps together in what had become pouring rain.

In 1978, an elderly couple in San Diego decided to sponsor, through their church group, five young Vietnamese men and one six-year-old girl from a refugee camp in Singapore. Mr. Russell was a retired Navy man. He had once been stationed in the Pacific and remembered the people there as being small and kind. When Mr. Russell heard about the Vietnamese boat people, he spent many sleepless nights staring at the ceiling and thinking about the nameless, faceless bodies lying in small boats, floating on the open water. In Mr. Russell’s mind, the Vietnamese boat people merged with his memories of the Okinawans and the Samoans and even the Hawaiians.

One night, Mr. Russell fell asleep and dreamed that the boats were seabirds sitting on the waves. He saw a hand scoop the birds up from the water. It was not his hand and it was not the hand of God.

The birds went flying in all directions across the blinding blue sky of Mr. Russell’s dream, but finally he saw them fly in only one direction and that was toward the point where in the dream he understood himself to be waiting, somewhere beyond the frame.

The original plan was that my father, the four uncles and I would live with the elderly couple, but as our papers were being processed Mr. Russell died and there was some question as to where we would be sent. Tokyo? Sydney? Minneapolis?

Mr. Russell had told Mrs. Russell his dream about the birds. After his death, she considered the dream and decided that we should move in with their son, Melvin.

Ba said it was no one’s fault that we lasted only one season at Mel’s place.

When Mel approached us at the airport, we heard a faint rattling: a ring full of gold and silver keys hang- ing from his belt. With each step Mel took, the ring swung and rattled by his side. The keys were new to him. Mel was tall and thin, but the ring looked fat, important. Mel caught the ring and pushed it into his pocket. This silenced the keys for a moment. He shook everyone’s hand—including mine—and laughing nervously said, “Welcome to America.”

He then waved his hand in the air and when I followed it with my eyes, I saw a poster of a man and a woman at the beach, lying on striped towels, sunning themselves between two tall palm trees. Above the palm trees were large block letters that looked like they were on fire: SUNNY SAN DIEGO. The man was lying on his stomach, his face buried in his folded arms. The woman was lying on her back, with one leg down and the other leg up, bent at the knee. I looked through the triangle formed by the woman’s tanned knee, calf and thigh and saw the calm, sleeping waves of the ocean. My mother was out there somewhere. My father had said so.

After Mel and his mother took us to the room in Mel’s house where Ba, the four uncles and I would all be sleeping, they wished us goodnight and left us alone, closing the door quietly behind them. They stood in the hallway and we could hear them talking. Even without understanding a word of what they were saying, the tone of their voices troubled us. Had we been able to understand, we might have heard the following:

“I feel like I’ve inherited a boatload of people. I mean, I’ve been living here alone and now I’ve got five men I’ve never met before, and what about that little girl?”

“Dear, you know your father wanted them here.”

“Here in America, sure, but not here with me.”

“Well, it’s worked out that way. If your father were here—”

The woman started to cry.

“I’m sorry, Mother. I’m so sorry.”

We heard their footsteps move down the hallway toward the living room.

Inside the bedroom, we all remained quiet in our places. Ba was standing with his back against the door. The four men were sitting on the two bunk beds and I was sitting on the double bed, my knees pulled up near my chest.

One of the uncles took a deep breath and lay down on the bed. He was still wearing his shoes and let his feet hang off the edge of the bed so he wouldn’t get the covers dirty.

Ba stepped forward and explained to the four men and me that Mel had bought our way into the United States. He said that Mel was a good man. We heard without really listening. We nodded. Ba said that Mel had let the people at the airport gates know that it was O.K. for us to be here. “If it wasn’t for him,” Ba said, “they would have sent us back the way we came.”

We each thought of those long nights floating on the ocean, rocking back and forth in the middle of nowhere with nothing in sight. We remembered the ships that kept their distance. We remembered the people leaning over the decks of the ships to study us through their binoculars and not liking what they saw, turning away from our boat. If it was true that this man Mel could keep us from floating back there—to those salt-filled nights—what could we do but thank him. And then thank him again. Only why did it seem from the tones of the voices in the hallway as if something was wrong?

Ba said that we had to be patient.

Two of the uncles nodded. One closed his eyes. One lay down and turned toward the wall. I wrapped my arms around my knees and studied my bare feet. They were very clean; not a speck of sand or salt on them.

Ba said whatever we might come to think of Mel, we should always remember that he opened a door for us and that this was an important thing to remember.

There were things about us Mel never knew or remembered. He didn’t remember that we hadn’t come running through the door he opened but, rather, had walked, keeping close together and moving very slowly, as people often do when they have no idea what they’re walking toward or what they’re walking from. And he never knew that during our first night in America, as he and his mother sat on the living room couch holding on to each other and crying because Mr. Russell was gone, Ba had climbed out the bedroom window and was sitting in the shadow of the palm trees on the front lawn of the house, staring at the moon like a lost dog, and also crying.

. . .

The ring of gold and silver keys that rattled beside Mel opened the doors to condominiums, duplexes, and town houses in various states of neglect. Mel was not good with tools and, since a bicycle accident in early childhood, was generally rather fearful, a fact that had always pained him, especially around his father. In exchange for letting us live with him—an arrangement he reluctantly agreed to, to satisfy what his mother called his father’s “dying wish”—Mel employed Ba and the four uncles as his crew of house painters and general maintenance men. He was relieved not to have to climb shaky ladders or crawl through dark, narrow spaces to see about small broken things.

When the white walls in one of his properties had faded or become dirty with the grubby prints of people’s lives rubbing up against them, he sent Ba and the four uncles in with directions to “touch them up,” “make like new,” “make white again.”

On almost every day of the week, you could find them working: five small-boned Vietnamese men climbing ladders in empty rooms, painting the white walls whiter.

“So much white is unlucky.”

“Layers of white bury you.”

“In between the first coat and the third—”

“Death could slip in and—”

“Press you up against the wall and—”

“Wrap you up in coats of white.”

“Dressing you for your own funeral.”

. . .

Of all the men, Ba knew the most English; he had picked some up from the Americans during the war. The uncles asked Ba to ask Mel why the walls had to be so white. Ba didn’t know the word “so.” His question came out like this:

“Why white?”

Mel said, “It’s clean.”

That was the end of the conversation.

When Ba told the uncles what Mel had said, they stared at him blankly.

“No,” they said, turning to the white walls. “We don’t understand.”

They picked up their paintbrushes and rollers and rags and went back to work.

Ba tried to tell them again, the way Mel had told him, in that voice that shines bright in your face like a flashlight aimed at your eyes when you’re sleeping. It’s a voice that doesn’t explain, though it often says things in tones that make you wonder. My Ba does not have such a voice. Ba’s voice echoes from deep down like a frog singing at the bottom of a well. His voice is water moving through a reed pipe in the middle of a sad tune. And the sad voice is always asking and answering itself. It calls out and then comes running in. It is the tide of my Ba’s mind. When I listen to it, I can see boats floating around in his head. Boats full of people trying to get somewhere.

. . .

Mel had stopped going to church years ago but after his father’s death, he started going again. Every Sunday morning he would drive to his parents’ house to pick up his mother and accompany her to church. During our first month at Mel’s, Ba and the four uncles and I would all pile into the car and go with them. But after a couple of Sundays in a row during which the uncles either slept through the sermon or stared at the floor absentmindedly, picking dried paint off their hands and fingernails, it was decided that we should stay at the house while Mel and his mother went to church.

After church, Mel would bring his mother by to visit with us.

We would all gather around the coffee table in the living room, Mel seated on the lounge chair in the corner, reading the Sunday paper, Ba, the four uncles and I taking turns smiling at Mrs. Russell, who sat on the couch and smiled patiently back at us.

“Now, what’s happening in the world?” she’d ask Mel.

“Oh, the usual,” he’d answer.

Mrs. Russell’s face was always made up, and when I leaned in reluctantly to kiss her, it smelled of sweet powder and rouge. She wore necklaces and earrings with bright purple and red stones. Some of the earrings were in the shape of flowers and some hung like clusters of lights shining from either side of her face.

From that house of bachelors, Mrs. Russell chose my Ba and me as her favorites. Perhaps she sensed we’d once had a woman in our lives. She bought me pastel-colored dresses to wear to school and smaller versions of those necklaces and earrings she liked to wear. The jewelry came cushioned on cotton squares inside little white boxes that rattled hollow when she shook them.

On Sunday afternoons that first winter, she would take my Ba and me for long drives up into the mountains. After the telephone wires and the streets of the city had slowly given way to treetops and gravel roads, we would get out of the car and find ourselves surrounded by snow. A small woods stood before us, and the road fell away in the distance behind us. There was nothing up there but snow and sky. And it seemed that all we ever did was walk in circles, making footprints in the soft snow.

After the third trip to the mountain, I asked Ba why Mel’s mother was always taking us up to the snow.

He said, “Maybe she thinks we think it’s magic, the way she can take us to a snowy place that’s so near a hot city.”

“Why doesn’t she take us to the beach?” I asked.

Ba shook his head. “No. Not possible. There’s no reason for us to go there.”

“But Ma’s there,” I said.

“No, she’s not,” Ba said, leaning down to zip up my jacket.

“You told me she was at the beach,” I said.

“Not the beach here. The beach in Vietnam,” Ba said.

What was the difference?

The grandmother brought a small camera with her on these trips. She liked looking at things through it. On our very first trip to the mountain, she took a photograph of Ba and me standing in front of Mel’s blue car.

In the photograph, Ba is wearing brown pants and a turquoise velour sweatshirt. His hair is parted on the side and pushed back behind one ear. I am wearing blue jeans and a yellow-and-red striped sweater that you can’t see because it’s under the ivory-colored sweater the grandmother had pulled from the trunk of the car, shaking the dust off before helping me into it. Before we took this picture Ba brushed my bangs across my forehead so they wouldn’t fall in my eyes.

In this photograph, my Ba and I hold hands and lean against the blue car. We are looking at the camera, waiting for that flash that lets us know something has happened inside the body of the camera, something that makes it remember us, remember our faces, remember our clothes, remember the blurred shape of our hands captured in that second when we shivered, waiting.

After the grandmother took this picture, she led us toward the woods.

. . .

That first day on the mountain, I made a game of following in my Ba’s footsteps so I left no tracks of my own in the snow. When I stopped and looked back in the direction we had come from, I could see only my Ba’s footprints and the grandmother’s. The footprints began at the car, which looked, from a distance, like a shining blue box that had dropped from the sky.

I watched Ba walking slowly toward the woods. He had his hands behind his back and was staring at the ground. The grandmother walked ahead of him. She was looking through her camera at the sky, at the tops of trees and, sometimes, back at us.

I ran after them.

In the thickest part of the woods, she stopped walking and turned to face us. She was smiling and I remember how her head shook slightly, sending the shiny balls on her earlobes swinging like searchlights.

She laid her palm against the trunk of a tree and with her finger traced some letters that had been carved there. She was smiling and crying at the same time.

I closed my eyes. When I opened them, Ba was squatting in the snow with his eyes closed and his hands to his ears the way I used to squat in the shadow of the fishing boats at home when we played hide-and-go-seek, my eyes shut tight so no one could see me. I ran over to Ba and threw my arms around his neck and climbed onto his back.

“Where’s my Ba?” I asked, pretending he was a big rock. “I wonder where my Ba is hiding in all this snow.”

The big rock stood up and became a tree. The tree tried to shake off all the snow that had gathered on its branches. I held on tightly and the tree became a wild horse whose neck I clung to as it went running across the fields. The horse ran and ran and ran. And as it ran, it asked itself, “I wonder where my little girl has disappeared to.”

I put my hands in front of my Ba’s eyes and wiggled my fingers like ten squirming fish out of water. I said, “Ba! Ba! Here I am! I’m right here!”

We galloped out of the woods, stamping designs into the snow. We shouted each other’s names and let them echo all around. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the woods getting smaller. When Ba stopped running to catch his breath, I heard the light crunching of the grandmother’s steps, somewhere far behind us.

Ba and I envied the four uncles. They were never invited to come with us on the mountain drives. They spent their Sunday afternoons walking around the neighborhood, looking for signs of other Vietnamese people. It took them a while but they finally found some other Vietnamese men at a pool hall. Every Sunday after that, they would return to the pool hall.

While Ba and I were following the grandmother around in the snow, the uncles were smoking cigarettes, drink- ing iced coffee, shooting pool and learning to watch and then bet on football games with their new Vietnamese brothers. They had such a good time they wouldn’t come home until late on Sunday nights. Ba and I would wake up early on Monday mornings and find the uncles asleep on their bunk beds.

Often they would still have their coats on and one uncle, sleeping on a top bunk, never managed to kick off both his shoes. Ba would lift me up and I would wiggle the shoe from side to side until I could pull it off the uncle’s foot. Then I would fish under the bed for the shoe that had been kicked off the night before. I would pair the shoes and leave them in the middle of the room, with their toes pointing toward the door.

Weekday mornings, after I’d brushed my teeth and washed my face, Ba would hand me one of the pastel-colored dresses the grandmother had given me. I’d pull the itchy, rustling dress over my head and let it hang for a moment around my neck, a huge flower whose petals were bunched and whose center had been replaced by my frowning face.

“I don’t want to wear American dresses,” I’d say to Ba.

Ba lowered the edges of his mouth and raised his eyebrows at the same time, like a clown about to cry. He shrugged his shoulders at me and reached under the bed for my school shoes, a pair of clear plastic sandals—also from the grandmother—that let the playground pebbles get stuck between my toes every time I kicked at the dirt.

I’d run around the room and let the dress rise up and down around my neck, like rooster feathers ruffling before a cockfight.

“Who wants to wear American dresses? Who?” Running in small circles I’d chant a litany of “Who? Who? Who?”

Ba would sometimes join me by standing on one leg and kicking back with the other, with his hands cupped under his armpits and his elbows jutting out like wings. Tilting his head to one side, he’d furrow his brow and chant, “Who? Who? Who?”

“Who’s there?” one of the uncles would ask, in a sleepy voice.

I’d run out of the room pulling the dress on in the hallway. From inside the room, I could hear Ba’s voice, reassuring. “It was only the girl, dancing.”

“Cooing like a common pigeon,” another of the uncles would complain.

“Every morning that girl runs around like a headless chicken,” said another.

“Isn’t she late for school?” asked yet another.

I’d stand in the hallway, leaning casually against the wall, my legs crossed at the ankles. After a minute, Ba would come out of the room, quietly closing the door behind him. He’d hand me my plastic sandals. I’d sit down on the floor of the hallway and slip them on. As I tightened the buckles, I could hear the uncles rolling around in their beds, groaning, trying to find the comfortable spot they’d lost upon waking.

Ba and I would tiptoe to the front door. Mel often slept until noon, so we all had to be quiet when leaving the house.

We’d stand on the sidewalk and Ba would comb my hair with his fingers. Then he’d pull two barrettes out of his shirt pocket, push my hair away from my eyes, and gently snap the barrettes in place.

As we walked toward the school, he’d often tell me not to make so much noise in the morning.

Once, he told me Mel had complained to him that he could hear me “chattering in his sleep.” When Ba told me that, I said, “Dumb birds chatter. I don’t chatter.” Ba squeezed my hand and didn’t say anything.

A block away from my school, Ba and I would stop at a red-and-white sign on the street corner and I’d put my arm around the post. We did this every morning. Ba would stand beside me and wait while I then wrapped one leg around the post and hung my head as far as it would go to one side.

I liked looking at things from this angle. Everything was upside down. I would look at the long gray chain-link fence that surrounded my school playground. I imagined how all the children standing with their feet pressed firmly against the ground, and their heads pointing toward the top of the chain-link fence, would slowly slip into the pale blue sky. I imagined the children floating, their dresses ballooning out around them as the wind ruffled their hair across their faces. I’d look over at Ba, also upside down, and I would imagine him floating too, with his hands folded across his chest.

While the blood was rushing to my head, Ba was studying the letters on the sign. He practiced reading the word. He would slowly part his lips and then close them, making this sound: “Suh-top!” “Suh-top!” “Suh-top!”

I was the only Vietnamese student at my school. On the first day of class, the teacher introduced me to the other students by holding a globe in one hand as she gave it a spin with the other, and then pointing with her finger at an S-shaped curve near a body of water.

Was that where I had come from?

As I stood before them in a dress the color of an Easter egg, with my feet encased in clear plastic sandals, the other students looked at the globe and then back at me again. Some whispered behind their hands. Some just stared. I imagined the stripes on my underwear flashing on and off, like traffic signals, under the dress.

At recess that first day of school, as I stood in the shadow of a big electrical box on the edge of the playground, I missed my older brother. Could he see me standing here? Was he wondering why I wasn’t playing with the other children? Wasn’t I exactly like our limp-footed schoolmaster in Vietnam? The one who used to stand in the doorway of the schoolhouse and watch his students run up and down the beach yelling,

“Hey! Who can run faster than me?”

“Who can jump higher than this?”

“Who can swim past the horizon and back before the end of recess?”

When the loud bell rang at the end of recess the students at my American school formed a line at the edge of the blacktop. In a line, my class walked into a big room with rows of plastic green mats on the floor. The mats were in groups of two or three, separated by shelves of children’s toys. Everyone lay down on a mat with eyes shut until we were given a signal to open our eyes again.

“Go to sleep now,” the teacher would say. “If you can’t sleep, close your eyes and try to rest. Close your eyes. That will help.”

Ever since my brother left, I’ve had a hard time taking naps. At school in America, I lay on the green mat and stared at the white ceiling. Sometimes I would see a blond baby doll lying beside me on the shelf of toys. I would entangle my fingers in her coarse hair and lie still, listening to the other students breathe. While the doll’s blue eyes were dutifully closed behind long brown lashes, I stared at the ceiling and studied the shapes I saw there: a chair, a tree trunk, the face of an old man, a sliver of moon.

I began to play with the ceiling, a game that I used to play with the sky when I was lying in the fishing boat on the sea. At that time, I thought that everyone and everything I missed was hovering behind the sky. The game involved looking for a seam to the sky, a thread I could pull. I told myself that if I could find the thread and focus on it hard enough with my eyes, I could tear the sky open and my mother, my brother, my grandfather, my flip-flops, my favorite shells, would all fall down to me.

Before I could find the thread that would split the ceiling wide open, a student wearing a cape and holding a silver stick with a shiny star at its tip would come around to wake us. The star-holder shuffled quietly among the sleeping bodies, touching the star to one after another. The sleeping students stirred and woke. But when the star-holder came to wake me, I always sat up before he could touch me. Once, I forgot that my fingers were still entangled in the doll’s hair. As I sat up, her body jerked forward with me, knocking the plastic fruit off the shelf. Apples and oranges bounced onto the floor. That day, the star-holder hurried past me.

“Shhhh!” My teacher said, pressing a long finger against her fish lips. “Shhhh!”

Over the years, Mr. and Mrs. Russell had collected small glass figures of animals, mainly horses. The animals had skinny glass legs you could see through, as through a clean window. After Mr. Russell’s death, Mrs. Russell decided that her son Melvin should have some of these glass animals, along with a number of other things that had once belonged to his father.

One Sunday afternoon Mel and his mother pulled up to the house and Mel called for Ba and the uncles to come out and help him. A glass display cabinet was wedged in the open trunk of Mel’s car. After directing a couple of the uncles to maneuver the cabinet carefully out of the trunk, Mel told Ba and the other uncles to get the three cardboard boxes sitting on the backseat and then he waved for everyone to follow him. With his mother holding the front door open, Mel led the uncles and Ba up the five uneven steps and into the house. They carried the cabinet and the three boxes down the long hallway and around to the back of the house, to a room that was Mel’s office. I followed behind them, my hands tucked in the back pockets of my jeans.

Mel’s office was a small and crowded room. Half-emptied boxes lay on the floor. Shelves bowing under the weight of books and files lined the walls, and in the cen- ter of the room was a large square desk, its top covered with pens, papers, receipt books, a tray of keys and spare change. Behind the desk was a leather swivel chair.

Mel directed the uncles to place the glass cabinet in the far corner of the room, so that while sitting at his desk, he could look up and see into the cabinet.

As we stood watching, Mel and his mother unpacked the contents of the three cardboard boxes and placed them carefully inside the glass cabinet. First we saw five pieces of blue-and-white china. Then came some red leather-bound books. Mel spun the wheels on a toy fire truck before placing it inside the cabinet. His mother unwrapped a pipe that still had tobacco in it and handed it to Mel. Mel lay the pipe down on its side gingerly. The last to come out were the glass animals. There were about twenty of them and they were lined up in pairs, like animals in a parade.

We were invited to look into the glass cabinet. As we stood peering in at the contents, the old woman told Mel to tell Ba to tell the four uncles and me that the things inside were not for touching.

Ba didn’t tell us anything; he just asked us, “Do you understand?” and the four uncles and I said, “Yes.” We had all sensed that the things in the cabinet were valuable, not because they looked valuable to us but because they had been separated from the disorder of the rest of the room and the rest of the house.

As we were leaving Mel’s office, I noticed a golden brown butterfly lying atop some papers on his desk. I reached to touch it. Instead of the powder that usually comes off of butterfly wings, my fingers brushed across cold glass. Pausing in the doorway, I glanced over my shoulder toward the desk. What was that?

. . .

At the beginning and the end of every school day, two older students stood in the middle of the street across from the school entrance; they carried signs they crossed like sabers in battle. This meant the cars—all of them, every one of them, even the big yellow buses—had to stop so the children could cross the street to go to school or cross the street to leave school and go home, wherever home might be.

Each afternoon I would run past the crossed signs to meet whichever uncle had come to walk me back to Mel’s house. As the uncle and I passed the red-and-white sign at which Ba and I paused every morning, I’d brush my fingers against the post and whisper, “Hi.”

The uncle would let me into the house and I would race down the hallway to our room and change out of the itchy dress into my jeans and a T-shirt. I usually had an hour alone before Ba or one of the other uncles would come home and start dinner.

At first I used to spend the hour coloring or studying the reading book with pictures of the boy, the girl, and their dog, Spot, who liked to chase after the bouncing ball. But after the day we had watched Mel fill his cabinet, I would sneak into Mel’s office and spend the hour visiting with the butterfly and the glass animals.

The butterfly was golden brown and I found it lying as before inside the thick glass disk atop the stack of letters and rent receipts on Mel’s desk. When I picked up the disk, I saw that the butterfly was trapped in a pool of yellow jelly. Though I turned the glass disk around and around, I could not find the place where the butterfly had flown in or where it could push its way out again.

I held the disk up to my ear and listened. At first all I heard was the sound of my own breathing, but then I heard a soft rustling, like wings brushing against a windowpane. The rustling was a whispered song. It was the butterfly’s way of speaking, and I thought I understood it.

I cupped the disk in my palms and, gazing down at the butterfly, carried it over to the window overlooking the back garden. When I held it up to the sunlight, the disk glowed a dazzling yellow and at the center of the yellow was the rich earthen brown shape of the butterfly.

I carried the disk back to the desk and put it back atop the stack of letters and rent receipts. It pressed down on the paper the same way my Ba’s heavy head pressed down on the pillow at night, full of thoughts that dragged him into nightmares when all he wanted was a dream as sweet and happy as the taste of jackfruit ice cream.

When Ba and I lay down to sleep one night, I whispered into Ba’s ear, “I found a butterfly that has a problem.”

“What is the problem?” Ba asked.

“The butterfly is alive . . .”

“Good,” Ba said.

“But it’s trapped.”

“Where?”

“Inside a glass disk.”

Ba said nothing.

“But it wants to get out.”

“How do you know?”

“Because it said this to me: ‘Shuh-shuh/shuh-shuh.’ ”

Ba sat up, shook his heavy head back and forth and tapped on the side of one ear, then the other.

“What are you doing?” I asked him.

“I must get these butterfly words out of my head before they grow bigger,” Ba said, tilting his head far to one side so the words could slip out like water.

“Ahhh . . .” he sighed, pulling on his earlobes, “empty of all butterflies. Now I can sleep.”

The next morning, I went out to where the uncles were working, in a corner of the back garden. They were trimming plants, pulling up weeds, refilling the bird feeder. When one of the uncles asked me why I looked so serious, I told him that I needed his help. All the uncles stopped what they were doing and wanted to know what was wrong.

I explained with my fingers arching and meeting in an imperfect circle that there was a butterfly trapped inside a glass disk, and that when you held the disk up to the light—my arms now reaching toward the sun—the butterfly lit up, golden brown.

I asked the uncles to help me get the butterfly out.

“Impossible!”

“That butterfly got itself into a lot of trouble flying into a disk.”

“It’s not trouble we can do much about, though.”

“Yeah, what do we know about butterflies stuck in glass. I never saw anything like it in Vietnam.”

“But doesn’t it sound terrible?” I asked.

“It must be dead now, that butterfly.”

“Can’t do much for a dead butterfly.”

“No, I heard it rustle its wings. It wants to get out!”

“Listen to me, little girl, no butterfly could stay alive inside a glass disk. Even if its body was alive, I’m sure that butterfly’s soul has long since flown away.”

“Yes, that’s how I think of it also. No soul in that glass disk.”

“If there’s no soul, how can the butterfly cry for help?” I asked.

“But what does crying mean in this country? Your Ba cries in the garden every night and nothing comes of it.”

“Just water for Mel’s lawn.”

“Nothing.”

They went back to work.

Recenzii

“A brilliant evocation of human sorrow and desire. . . . Heartbreaking and exhilarating. . . . As vivid as a fairy tale, as allusive as a poem.”

The New York Times Book Review

“Breathtaking. . . . Flows in luminous paragraphs that mingle past and present, creating a fluid sense of time.” —Vogue

“Slender and elegant. . . . A beautifully rendered description of the personal, psychological and historical threads that link father to daughter.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

"lê captures the magical thinking of childhood with its shifting awareness of the wonders and apprehensions of life." —Village Voice Literary Supplement

The New York Times Book Review

“Breathtaking. . . . Flows in luminous paragraphs that mingle past and present, creating a fluid sense of time.” —Vogue

“Slender and elegant. . . . A beautifully rendered description of the personal, psychological and historical threads that link father to daughter.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

"lê captures the magical thinking of childhood with its shifting awareness of the wonders and apprehensions of life." —Village Voice Literary Supplement