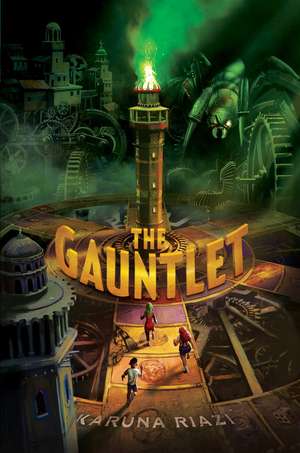

The Gauntlet

Autor Karuna Riazien Limba Engleză Paperback – 19 apr 2018 – vârsta până la 12 ani

Nothing can prepare you for The Gauntlet…

It didn’t look dangerous, exactly. When twelve-year-old Farah first laid eyes on the old-fashioned board game, she thought it looked…elegant.

It is made of wood, etched with exquisite images—a palace with domes and turrets, lattice-work windows that cast eerie shadows, a large spider—and at the very center of its cover, in broad letters, is written: The Gauntlet of Blood and Sand.

The Gauntlet is more than a game, though. It is the most ancient, the most dangerous kind of magic. It holds worlds inside worlds. And it takes players as prisoners.

Preț: 51.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 78

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.93€ • 10.37$ • 8.22£

9.93€ • 10.37$ • 8.22£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 05-19 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781481486972

ISBN-10: 1481486977

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (spfx: metallic stock)

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1481486977

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (spfx: metallic stock)

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Salaam Reads / Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Karuna Riazi is a born and raised New Yorker, with a loving, large extended family and the rather trying experience of being the eldest sibling in her particular clan. Besides pursuing a BA in English literature from Hofstra University, she is an online diversity advocate, blogger, and publishing intern. Karuna is fond of tea, baking new delectable treats for friends and family to relish, Korean dramas, and writing about tough girls forging their own paths toward their destinies. She is the author of The Gauntlet and The Battle.

Extras

The Gauntlet

![]()

FARAH HAD HER BACK pressed against the seat of the living room sofa, keeping a wary eye on the door as more party guests filed in while she played marbles with Ahmad.

“My turn, Farah apu!” Ahmad shouted with seven-year-old enthusiasm, startling strangers. “My turn!”

He sat beside her on the floor, a box of chenna murki placed in front of him. He offered her a bite of the soft, tender, marble-sized morsels of sweet cheese, which he’d chomp by the handful. “Want one?” he asked, offering her a piece.

Farah wrinkled her nose at the treat. She didn’t do sweets, not even the Bangladeshi kind that the rest of her family devoured. She liked to think of herself as a bit of a rebel, at least in this small way.

“Don’t you want to try some of the snacks Ma made? Samosas or pakoras. Or do you want to talk to Essie and Alex?” Farah asked. She was always in convincing mode when it came to Ahmad. “We haven’t seen them in a while.”

“He wants to play with you, Farah, that’s all,” Essie said, looking down at Farah from her seat on the sofa.

Farah’s only other friend, Alex, was seated in an armchair nearby, running a hand through his thick curls, his nose firmly planted in a book. He hadn’t spoken a word to her, or anyone else, since the quiet greeting he’d spared when he came through the door. While Alex had never been a big talker, this indifference was new.

Today was the first time Farah had seen either Essie or Alex in months. It felt as though their friendship had been . . . not dented, not shattered, nothing so terrible and threatening and nearly beyond repair. Just a little loosened out of its socket.

“Let’s play. You and me,” Ahmad said. “You can have the good marbles this time.”

Farah smiled at him. Ahmad was only seven, she had to remind herself when she got frustrated. Just as she had lost friends in their move from Queens to the Upper East Side, he had lost his friends too. Friends for Ahmad were harder to come by, given his issues. Even on her birthday, when she felt the universe owed her gentle understanding that she didn’t always want to play with her baby brother, she couldn’t deny him and his gap-toothed smile.

“Okay, one more game,” she said, drawing a chalk circle on the floor.

He arranged the marbles in a plus sign. “Me first.”

“Of course.”

He pressed his knuckle to the floor and shot a finger forward. His favorite cat’s-eye marble struck the others, expertly scattering them. Three flew out of the circle, and one hit a nearby shoe.

Aunt Zohra.

She hovered over Farah and Ahmad for a moment, then picked up the box of sweets from the floor, popping a few chenna murki into her mouth.

“My cheese marbles!” Ahmad shouted, leaping for the box.

Aunt Zohra’s thin lips formed what passed for a smile. On anyone else it might be a grimace. She was scarecrow thin and fence-post tall. She wore a salwar kameez without any embroidery, unlike the fancy, glittering mirrors that adorned Farah’s own sky blue hem and long sleeves. She handed Ahmad the box, and he greedily scooped up more sweets.

“Why don’t you join your guests, Farah?”

“I would, but . . .”

“I’m winning, Zohra Masi,” Ahmad explained.

“Ahmad,” Aunt Zohra said gently, “I need to celebrate with the birthday girl, and so do the others. We must not keep her guests waiting.” Aunt Zohra was pretty good with Ahmad, considering how infrequently Farah and Ahmad saw her; Aunt Zohra mostly kept to herself. And even when she visited the family, she didn’t talk much. Her mind always seemed to be elsewhere.

“They’re not really my guests. Mostly aunties, and kids from my new school. I’d rather stay here.” Farah thought that Aunt Zohra might understand. After all, she wasn’t much for socializing either.

Aunt Zohra flashed Farah another smile. “Well, it is your birthday. You should have some fun. My gift for you is waiting upstairs. We can open it after the party. I think you’ll find a good use for it though. Better than I ever did.”

“Is the present in your room, Zohra Masi? Can I get it? Can I open it?” Ahmad aimed a kick at Farah’s shin, which, from years of practice, she dodged. Today’s tantrum was nothing new. Trying to avoid just this scenario, Baba and Ma gave Ahmad gifts even on Farah’s birthday to keep his antics to a minimum.

He balled up his fists and bellowed, “Please! Please! Let me open it, Farah apu.” When he reached this point of excitement, you couldn’t even see his eyes anymore. He squeezed them so tight, folding them away in the same manner he might if he were wishing on birthday candles or trying to compress himself out of existence.

For a second, Farah thought his disappearing wouldn’t be such a bad thing: calling down a goblin king to whisk him off into the deep, dark depths of a fairy labyrinth or sidestepping himself into another dimension.

Still, it was Farah and Ahmad, Ahmad and Farah. She didn’t know what life would be without him.

“It’s a present for me. For my birthday. You got your present earlier. Those shiny new marbles,” Farah said. She knew that Ahmad’s ADHD meant he couldn’t always control himself. Baba said Ahmad had moments where he was trapped in his own overwhelming emotions, like being lost in a frustrating maze, and Farah had to be patient until he found his way out again.

Baba was in the dining room with Uncle Musafir talking about the new offices his software business would be settling into. He did not have to deal with Ahmad or his mazelike mind right this second.

“Ahmad, I have something to show you,” Aunt Zohra said, flashing her Turkish puzzle rings. They glimmered in the light, delicate on Aunt Zohra’s long, lanky fingers.

His eyes grew big. They had never played with Turkish puzzle rings before, but as a game-loving family, they had of course heard of them. Each ring was made up of interlocking thinner rings, forming a beautiful intricate design, like a series of golden waves. Aunt Zohra winked at Farah over his head.

“Wait! My marbles first!” Ahmad skittered away like one of his precious marbles, darting under a nearby couch to retrieve them. Aunt Zohra trailed after him. Farah felt a guilty, giddy rush of relief.

Aunt Zohra coaxed Ahmad out and toward the kitchen, where Ma was no doubt keeping busy. Farah watched her mother work through the pass-through window: She stirred the pots brimming with simmering sauces and curries and steaming rice, picked up each spice jar carefully lined up on the counter, and sprinkled the bright, colorful aromatics over the food.

The front door opened and closed, and more and more of the kids from her new school filed in through the doorway. Most of them were accompanied by their mothers, with a few harried-looking nannies bouncing younger siblings on their hips and locating odd corners to deposit overflowing diaper bags. They waved and said nice, polite, meaningless things.

Farah knew she should go greet her guests. It was the right thing for a good Bangladeshi girl to do. But most of these kids were still strangers to her, and she was a stranger to them. On her birthday, she wanted to avoid having the kind of small talk that happens between not-really-friends. She especially didn’t want to discuss her scarf. It was a question that Farah had never heard at her old school. She hadn’t been the only hijaabi in her class in Queens. There, everyone had known the proper name for it and did not try to tug at the end or ask how her hair looked underneath it or if she even had hair. Now she went to a school in downtown Manhattan, where she was the only hijaabi in her class.

Farah moved herself to sit on the couch by Essie, who had busied herself with a game on her phone. Last year Farah would have had no problem breaking the silence and suggesting a fun thing to do. Now she felt unsure. Should she suggest they play Monopoly? They had spent hours playing board games last year. But today the suggestion felt little-kiddish. What if her friends didn’t enjoy board games anymore? Should she ask about school? Or would that only bring attention to the fact that she wasn’t there? And anyway, no kid wanted to talk about school. Farah’s thoughts were interrupted by Essie. “Let’s do something. . . . I’m bored,” she said.

“Me too,” said Farah. She immediately felt awful. This was her party, and her friends were already bored.

“Can we open some of your presents?” offered Alex, looking up from his book. “Maybe you got something cool.”

“My mom probably won’t want me opening any gifts until after the party. It would look rude taking them off the table around all the guests.”

“What about the gift your aunt got you? Didn’t she say it was upstairs?” asked Essie.

Farah thought back to the presents Aunt Zohra had given her over the years: a set of fruit patterned knives from the local BJ’s for Farah to “learn her colors,” clothes in the wrong size and in odd, erratic patterns from unfamiliar Bengali boutiques back in Dhaka. The kind of presents you’d expect from an absentminded grandmother at Christmas, ones offered without any particular meaning or thought.

“It’s nothing exciting, I’d guess,” she said. “But we might as well check it out.”

Farah, Alex, and Essie grabbed some snacks and headed upstairs, Essie balancing two plates piled high with samosas, fried vegetable pakoras, and one or two overly syrupy sweets that would no doubt spoil their appetite, Alex taking up the rear and anxiously peering over his shoulder to make sure their escape wasn’t noticed.

Farah’s aunt was staying in a guest room, and when they opened the door, they found Ahmad holding a square package wrapped in plain brown paper.

“That’s my gift!” Farah ran in and took it out of his hands. “How did you escape Aunt Zohra?” Not that Farah needed an answer. Ahmad was really good at wandering off without detection. It was one of the reasons Farah kept such a close eye on him whenever they went out.

Ahmad stood up on the bed and started jumping. “Open it! Open it!”

Farah didn’t know what was inside. Still, she was overcome by a feeling of something new, something strange, something hovering in the air, as fragrant and weighty as the steam off Ma’s cooking pots. It piqued her curiosity. She peeled back the paper, pushing away Ahmad’s greedy hands as she worked. Soon a polished wooden corner emerged.

Finally, the entire thing slid out of the paper into Farah’s hands. She held it up to the light as Alex craned his head over her shoulder.

It was a game. A board game, most likely. It had the same square shape of a regular game box, but it was sturdier, antique-looking. The dark wood was emblazoned with carved images: palaces with domes and elegant spirals and high arches, a fearsome spider with its fangs horrendously large and carefully rendered, an elegantly curved lizard, a sparkling minaret, and a wasp-waisted hourglass—and at the very center of its cover, in broad letters, was written THE GAUNTLET OF BLOOD AND SAND.

Essie’s eyes widened as she leaned forward to look, her mouth a small O of delight and excitement.

“Wow,” Alex breathed.

Ahmad jumped up and down with excitement. “I want it, Farah apu,” he said. “I want it!”

“What is it?” Essie said.

Farah’s hand paused over the wooden cover. “I . . . don’t know what this is.”

Before she even finished the sentence, the game started to vibrate.

CHAPTER ONE

FARAH HAD HER BACK pressed against the seat of the living room sofa, keeping a wary eye on the door as more party guests filed in while she played marbles with Ahmad.

“My turn, Farah apu!” Ahmad shouted with seven-year-old enthusiasm, startling strangers. “My turn!”

He sat beside her on the floor, a box of chenna murki placed in front of him. He offered her a bite of the soft, tender, marble-sized morsels of sweet cheese, which he’d chomp by the handful. “Want one?” he asked, offering her a piece.

Farah wrinkled her nose at the treat. She didn’t do sweets, not even the Bangladeshi kind that the rest of her family devoured. She liked to think of herself as a bit of a rebel, at least in this small way.

“Don’t you want to try some of the snacks Ma made? Samosas or pakoras. Or do you want to talk to Essie and Alex?” Farah asked. She was always in convincing mode when it came to Ahmad. “We haven’t seen them in a while.”

“He wants to play with you, Farah, that’s all,” Essie said, looking down at Farah from her seat on the sofa.

Farah’s only other friend, Alex, was seated in an armchair nearby, running a hand through his thick curls, his nose firmly planted in a book. He hadn’t spoken a word to her, or anyone else, since the quiet greeting he’d spared when he came through the door. While Alex had never been a big talker, this indifference was new.

Today was the first time Farah had seen either Essie or Alex in months. It felt as though their friendship had been . . . not dented, not shattered, nothing so terrible and threatening and nearly beyond repair. Just a little loosened out of its socket.

“Let’s play. You and me,” Ahmad said. “You can have the good marbles this time.”

Farah smiled at him. Ahmad was only seven, she had to remind herself when she got frustrated. Just as she had lost friends in their move from Queens to the Upper East Side, he had lost his friends too. Friends for Ahmad were harder to come by, given his issues. Even on her birthday, when she felt the universe owed her gentle understanding that she didn’t always want to play with her baby brother, she couldn’t deny him and his gap-toothed smile.

“Okay, one more game,” she said, drawing a chalk circle on the floor.

He arranged the marbles in a plus sign. “Me first.”

“Of course.”

He pressed his knuckle to the floor and shot a finger forward. His favorite cat’s-eye marble struck the others, expertly scattering them. Three flew out of the circle, and one hit a nearby shoe.

Aunt Zohra.

She hovered over Farah and Ahmad for a moment, then picked up the box of sweets from the floor, popping a few chenna murki into her mouth.

“My cheese marbles!” Ahmad shouted, leaping for the box.

Aunt Zohra’s thin lips formed what passed for a smile. On anyone else it might be a grimace. She was scarecrow thin and fence-post tall. She wore a salwar kameez without any embroidery, unlike the fancy, glittering mirrors that adorned Farah’s own sky blue hem and long sleeves. She handed Ahmad the box, and he greedily scooped up more sweets.

“Why don’t you join your guests, Farah?”

“I would, but . . .”

“I’m winning, Zohra Masi,” Ahmad explained.

“Ahmad,” Aunt Zohra said gently, “I need to celebrate with the birthday girl, and so do the others. We must not keep her guests waiting.” Aunt Zohra was pretty good with Ahmad, considering how infrequently Farah and Ahmad saw her; Aunt Zohra mostly kept to herself. And even when she visited the family, she didn’t talk much. Her mind always seemed to be elsewhere.

“They’re not really my guests. Mostly aunties, and kids from my new school. I’d rather stay here.” Farah thought that Aunt Zohra might understand. After all, she wasn’t much for socializing either.

Aunt Zohra flashed Farah another smile. “Well, it is your birthday. You should have some fun. My gift for you is waiting upstairs. We can open it after the party. I think you’ll find a good use for it though. Better than I ever did.”

“Is the present in your room, Zohra Masi? Can I get it? Can I open it?” Ahmad aimed a kick at Farah’s shin, which, from years of practice, she dodged. Today’s tantrum was nothing new. Trying to avoid just this scenario, Baba and Ma gave Ahmad gifts even on Farah’s birthday to keep his antics to a minimum.

He balled up his fists and bellowed, “Please! Please! Let me open it, Farah apu.” When he reached this point of excitement, you couldn’t even see his eyes anymore. He squeezed them so tight, folding them away in the same manner he might if he were wishing on birthday candles or trying to compress himself out of existence.

For a second, Farah thought his disappearing wouldn’t be such a bad thing: calling down a goblin king to whisk him off into the deep, dark depths of a fairy labyrinth or sidestepping himself into another dimension.

Still, it was Farah and Ahmad, Ahmad and Farah. She didn’t know what life would be without him.

“It’s a present for me. For my birthday. You got your present earlier. Those shiny new marbles,” Farah said. She knew that Ahmad’s ADHD meant he couldn’t always control himself. Baba said Ahmad had moments where he was trapped in his own overwhelming emotions, like being lost in a frustrating maze, and Farah had to be patient until he found his way out again.

Baba was in the dining room with Uncle Musafir talking about the new offices his software business would be settling into. He did not have to deal with Ahmad or his mazelike mind right this second.

“Ahmad, I have something to show you,” Aunt Zohra said, flashing her Turkish puzzle rings. They glimmered in the light, delicate on Aunt Zohra’s long, lanky fingers.

His eyes grew big. They had never played with Turkish puzzle rings before, but as a game-loving family, they had of course heard of them. Each ring was made up of interlocking thinner rings, forming a beautiful intricate design, like a series of golden waves. Aunt Zohra winked at Farah over his head.

“Wait! My marbles first!” Ahmad skittered away like one of his precious marbles, darting under a nearby couch to retrieve them. Aunt Zohra trailed after him. Farah felt a guilty, giddy rush of relief.

Aunt Zohra coaxed Ahmad out and toward the kitchen, where Ma was no doubt keeping busy. Farah watched her mother work through the pass-through window: She stirred the pots brimming with simmering sauces and curries and steaming rice, picked up each spice jar carefully lined up on the counter, and sprinkled the bright, colorful aromatics over the food.

The front door opened and closed, and more and more of the kids from her new school filed in through the doorway. Most of them were accompanied by their mothers, with a few harried-looking nannies bouncing younger siblings on their hips and locating odd corners to deposit overflowing diaper bags. They waved and said nice, polite, meaningless things.

Farah knew she should go greet her guests. It was the right thing for a good Bangladeshi girl to do. But most of these kids were still strangers to her, and she was a stranger to them. On her birthday, she wanted to avoid having the kind of small talk that happens between not-really-friends. She especially didn’t want to discuss her scarf. It was a question that Farah had never heard at her old school. She hadn’t been the only hijaabi in her class in Queens. There, everyone had known the proper name for it and did not try to tug at the end or ask how her hair looked underneath it or if she even had hair. Now she went to a school in downtown Manhattan, where she was the only hijaabi in her class.

Farah moved herself to sit on the couch by Essie, who had busied herself with a game on her phone. Last year Farah would have had no problem breaking the silence and suggesting a fun thing to do. Now she felt unsure. Should she suggest they play Monopoly? They had spent hours playing board games last year. But today the suggestion felt little-kiddish. What if her friends didn’t enjoy board games anymore? Should she ask about school? Or would that only bring attention to the fact that she wasn’t there? And anyway, no kid wanted to talk about school. Farah’s thoughts were interrupted by Essie. “Let’s do something. . . . I’m bored,” she said.

“Me too,” said Farah. She immediately felt awful. This was her party, and her friends were already bored.

“Can we open some of your presents?” offered Alex, looking up from his book. “Maybe you got something cool.”

“My mom probably won’t want me opening any gifts until after the party. It would look rude taking them off the table around all the guests.”

“What about the gift your aunt got you? Didn’t she say it was upstairs?” asked Essie.

Farah thought back to the presents Aunt Zohra had given her over the years: a set of fruit patterned knives from the local BJ’s for Farah to “learn her colors,” clothes in the wrong size and in odd, erratic patterns from unfamiliar Bengali boutiques back in Dhaka. The kind of presents you’d expect from an absentminded grandmother at Christmas, ones offered without any particular meaning or thought.

“It’s nothing exciting, I’d guess,” she said. “But we might as well check it out.”

Farah, Alex, and Essie grabbed some snacks and headed upstairs, Essie balancing two plates piled high with samosas, fried vegetable pakoras, and one or two overly syrupy sweets that would no doubt spoil their appetite, Alex taking up the rear and anxiously peering over his shoulder to make sure their escape wasn’t noticed.

Farah’s aunt was staying in a guest room, and when they opened the door, they found Ahmad holding a square package wrapped in plain brown paper.

“That’s my gift!” Farah ran in and took it out of his hands. “How did you escape Aunt Zohra?” Not that Farah needed an answer. Ahmad was really good at wandering off without detection. It was one of the reasons Farah kept such a close eye on him whenever they went out.

Ahmad stood up on the bed and started jumping. “Open it! Open it!”

Farah didn’t know what was inside. Still, she was overcome by a feeling of something new, something strange, something hovering in the air, as fragrant and weighty as the steam off Ma’s cooking pots. It piqued her curiosity. She peeled back the paper, pushing away Ahmad’s greedy hands as she worked. Soon a polished wooden corner emerged.

Finally, the entire thing slid out of the paper into Farah’s hands. She held it up to the light as Alex craned his head over her shoulder.

It was a game. A board game, most likely. It had the same square shape of a regular game box, but it was sturdier, antique-looking. The dark wood was emblazoned with carved images: palaces with domes and elegant spirals and high arches, a fearsome spider with its fangs horrendously large and carefully rendered, an elegantly curved lizard, a sparkling minaret, and a wasp-waisted hourglass—and at the very center of its cover, in broad letters, was written THE GAUNTLET OF BLOOD AND SAND.

Essie’s eyes widened as she leaned forward to look, her mouth a small O of delight and excitement.

“Wow,” Alex breathed.

Ahmad jumped up and down with excitement. “I want it, Farah apu,” he said. “I want it!”

“What is it?” Essie said.

Farah’s hand paused over the wooden cover. “I . . . don’t know what this is.”

Before she even finished the sentence, the game started to vibrate.