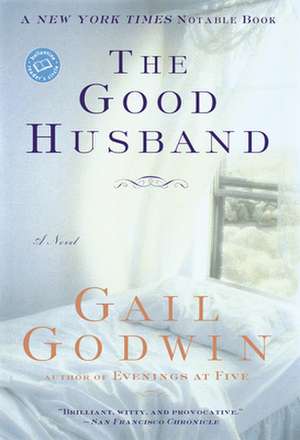

The Good Husband

Autor Gail Godwinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 1995

--San Francisco Chronicle

As a young woman, the brilliant and eternally curious Magda Danvers took the academic world by storm. Then, to everyone's surprise, she married Francis Lake, a mild, midwestern seminarian, who has devoted his life to taking care of his charismatic wife. Now, Magda's grave illness puts their marriage to its ultimate test.

Though facing her "Final Examination," Magda continues to arouse her visitors with compelling thoughts and questions. Into this provocative atmosphere comes Alice Henry, retreating from family tragedy and a crumbling marriage to novelist Hugo Henry. But is it the incandescence of Magda's ideas that draws Alice, or the secret of "the good marriage" that she is desperate to discover? For Alice, Hugo, Francis, and Magda will learn that the most ideal relationship--even a perfect marriage--doesn't come without a price....

"COMPELLING WRITING...REMARKABLY SKILLFUL...Gail Godwin shows herself to be at the height of her considerable power as a storyteller and a writer."

--The Boston Globe

"ONE OF HER FINEST BOOKS...It is not only a well-written story, but a mature and wise one, affirmative in its vision of love, unblinking in its portrayal of tragic loss."

--Atlanta Journal & Constitution

"FASCINATING...[A] BIG SUMPTUOUS BOOK...HER BEST NOVEL."

--Entertainment Weekly

"A BRILLIANTLY CRAFTED NOVEL, full of fun and mischief and resonating with wisdom and moral depth."

--New Woman

A Featured Selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club

Preț: 121.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 182

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.17€ • 23.88$ • 19.41£

23.17€ • 23.88$ • 19.41£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-17 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345396457

ISBN-10: 0345396456

Pagini: 498

Dimensiuni: 140 x 207 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Ediția:Ballantine Trad.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345396456

Pagini: 498

Dimensiuni: 140 x 207 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Ediția:Ballantine Trad.

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

Chapter 1

Magda Danvers, the week before Christmas, returned home from surgery at Catskill Hospital and telephoned to her chairman she would not be meeting her classes for second semester. “It seems the Great Uncouth has taken up permanent residence inside me,” she informed him. “Well, I always was a good student; now I must see what I can learn from my final teacher.”

She had many visitors. This was during the first stage of her dying, when she still looked and spoke like her old self. Ray Johnson, the chairman of the English Department at Aurelia College, lost no time in disseminating her audacious remark around campus, and people wanted to go over to the restored Colonial farmhouse their prized teacher shared with her husband, Francis Lake, a devoted, self-effacing man much younger than herself, and see for themselves how Magda would go about learning from her final teacher.

During the remainder of deep winter, Magda held court in her snug upstairs study, crammed with all her books, surrounded by her beloved Blake reproductions. She reclined on the worn leather sofa in a baggy sweater and old tweed trousers and red velvet carpet slippers, an afghan spread over her, her famous mahogany hair floating loose around her shoulders rather than pinned up in its usual fat twist. A fire crackled in the small fireplace, tended by her husband. At regular intervals, Francis would poke his head around the door and ask, “How is the fire doing, my love?” If she replied, “We could use a couple more logs, Frannie,” that was their signal that she was enjoying her visitor, and Francis would slip in unobtrusively and rekindle the fire. If she said, “I think we’ll just let it burn itself out,” that meant the visitor was not contributing enough to the precious time she had left in this world, and Francis was to return in three to five minutes and announce it was time for one of Magda’s obligatory reset periods in the bedroom at the other end of the hall.

Her students came. Suzanne Riley brought Magda her map of the Mountain of Purgatory, Magda’s last class assignment before entering the hospital. “I want you to have the original of this, Professor Danvers. I mad a color photocopy to hand in to Professor Ramirez-Suarez. He’ll be taking your classes second semester while…until…” The girl looked away miserably.

“It’s okay, Suzanne,” Magda soothed her. “We both know what you mean. But this is a gorgeous map. All the detail you put into these figures. I didn’t even assign figures.”

“Well, I am an arts major. At first I dreaded your assignment. You know. All that extra work. I mean, if you’re going to draw a really good map, you have to read the stuff really carefully so you’ll know what to draw. But then it was weird. I got really involved. I always know when I get involved while I’m drawing because my mouth begins to water. If that doesn’t sound too gross.”

Francis Lake poked his head briefly around the door. “How’s the fire doing, Magda?”

“Oh, pile on some more logs,” replied Magda cheerfully. “But first, come and look at this splendid drawing. I want to get it framed as soon as possible and hang it up with my Blakes so I can look at it in the time I’ve got left. A good map of Purgatory fits in perfectly with my present studies. Let’s see, where am I on the Mountain? I’d like to be as far up as the Gluttonous cornice–the warm sins are better–but I’m probably still down in lower Purgatory with the cold and proud. Where do you think I am, Frannie?”

“You’re certainly not cold and proud,” said Francis. “It is a splendid map. I’ll take it down to the framers first thing in the morning, my love.”

First, my grandmother dies, and then my girlfriend breaks up with me, and now I’m losing my favorite teacher,” blubbered the young man, clutching at Magda’s afghan. “This has been the worst year of my life. I’m like, wondering what’s the point of living.” He covered his face with a corner of the afghan, managing to tug it off Magda’s knees in the process, and began to sob in earnest.

Francis Lake’s slim figure materialized at once in the doorway. “How’s the fire doing, Magda?”

“Oh, dying, like everything else in here,” said Magda. “Could you give Rick a Kleenex so he can blow his nose before he goes?”

Ramirez-Suarez paid courtly visits. “We miss you, bright lady. My task this semester is to make Paradise as interesting as Hell. You would have done a much better job with your marvelous viveza. I have been entertaining them a little by reading passages aloud in the Italian. Oh, and I have had to supplement the text with my own notes, which I pass out to them each session. Magda, these young people have no receptivity to allusions. They don’t know who Achilles was. They can’t name the seven deadly sins. Their biblical references are almost nil. Would you believe it, many of them weren’t familiar with the Sermon on the Mount.”

Her husband, smiling, stuck his head in the door.

“Ah, Francis, I have stayed too long and tired out our dearest Magda,” said the dapper little professor, leaping out of his chair.

“I’ll be tireder if you leave me, Tony. Frannie just came to heap more logs on our fire. And then you’ll have some tea with us. After you phoned this morning, Francis went out and bought those lemon squares you like.”

“Oh, dear lady–“

“Sit down, Tony. Haven’t you heard that invalids are always supposed to have their way? You know, I think we ought to propose a new course at Aurelia. A required course, and not just for the liberal-arts majors, either. The catalog description would describe it as ‘The very minimum of people, places, and things you’d better at lest have heard of if you plan to pass yourself off as an educated person.’ And we’d stuff it into them any old-fashioned way we could: forced memorization, pop quizzes, all the dirty old tricks. A two-semester course. We could call it Allusions One, and Allusions Two…”

The chairman of English, Ray Johnson, dropped by regularly, his shining eyes behind the round glasses taking in the minute details of her decline so he could report back to others.

“Tony Ramirez-Suarez said he found you in excellent spirits the other day. You two were cooking up some amusing new course?”

“Allusions One and Two,” said Magda. “ ‘Would you rather drink from the waters of Lethe, the Pierian Spring, or Parnassus’s Waters? Why?’ ‘What did Circe do to men?’ ‘Why did Diana keep to the woods?’ ‘List the seven deadly sins and the four cardinal virtues and the four levels of meaning.’ Just the basic stuff you need if you’re going to read a poem rather than a balance sheet.”

The chairman chuckled knowledgeably. Magda’s mind definitely hadn’t succumbed to the waters of Lethe yet, but her flamboyant dark red hair, he hadn’t failed to notice, now sprouted an untidy inch or more of dead white at the parting. This shocking sign of the arrogant Magda’s deterioration somewhat tempered his resentment of her for baiting him. He could get three out of four levels of meaning, but what the devil were the four cardinal virtues? Parnassus’s waters rang a faint bell from somewhere in his academic past, but what the hell did you get from drinking them?

He changed the subject. “Poor Alice and Hugo Henry. They lost their baby.”

“Oh, no! How?”

“He got tangled in the cord and the oxygen was cut off. Apparently it was going fine until the last minute, Hugo said. He seemed quite shaken when he came to school today. It was a home birth. That Dr. Romero all the mothers love and all the obstetricians hate.”

“Oh, poor lovely Alice. And she was so happy when I was with her at your party in early December. Oh, God, there we both were, laughing and talking together, her with her healthy baby inside her and me with my undiagnosed cancer inside me, both of us oblivious to our fates…”

Francis Lake appeared in the doorway.

“Francis, Alice and Hugo lost their baby.”

“When?”

“Last Thursday,” said Ray Johnson. “But we didn’t know about it until Monday, when Hugo came to meet his classes.” The chairman then repeated the sad details to Magda’s husband.

“Oh, I’m so upset of them,” wailed Magda, clutching at her hair. “Francis, I must write them a letter immediately.”

“After you’ve rested,” Francis told her sternly. “Ray, you won’t mind waiting here until I get Magda settled in her room. Then we’ll go downstairs and have some tea. If you can spare the time.”

“Oh, I can always spare the time for one of your famous teas,” said the chairman, laughing.

January’s calendar flipped over into February, then on into March. Gresham P. Harris, president of Aurelia College, mounted the stairs behind Magda’s husband.

“Last time, we went thataway,” remarked the president lightly when Francis, at the top of the stairs, turned right, not left toward Magda’s study with the nice fire burning.

“Magda is staying in bed today.”

“Oh, I see,” said the president, preparing himself not to show anything as he followed Francis Lake toward a room at the other end of the hallway.

“Magda, Magda,” was all he said, when he saw his brilliant star lying gray and docile under the blanket in the big four-poster bed. She was small, she who three months ago would have been described by her aficionados as “statuesque,” and by her enemies (for of course she had those, too) as overweight. Since his last visit to the house, she must have dropped twenty or thirty pounds. And the wiry white stuff bursting out of her scalp belonged to someone else. Some wild old woman…or man. The glossy dark red hair that had been distinctly hers, though everyone knew it came out of a package, still lay in straggles of its former glory on either side of her pillows. It had the look of having just been brushed out for his visit, probably by Francis Lake.

The president sat down in the chair Magda’s husband placed for him on the right side of the bed. Left alone in the room by Francis in the direct range of the dying woman’s penetrating gaze, he gained a few moments of respite by plucking at the knees of his perfectly creased trousers and surveying the neat lines of his black-stockinged ankles and thep9olished black wing-tip shoes below. He was a well-groomed, fastidious man who appeared younger than his fifty-eight years. He and Magda were the same age. Years ago, they had been graduate students at the same time in Ann Arbor, but they hadn’t known each other. These days he also gave his smooth, dark hair a little help from a package. College presidents were expected to look younger now.

I, too, could be struck by cancer and waste away in a few months, the president suddenly realized. His gaze meeting Magda’s snapping dark eyes at last, he had the distinct feeling that she had read his thought word for word. It made it easier for him to speak naturally.

“Well, Magda, this distresses me. I guess I was hoping for a miracle. Now that this Gulf War is over, I’ve rescheduled our Twenty-fifth Anniversary Alumni Cruise around the British Isles for August–our first cruise ever, to honor Aurelia’s first graduating class of sixty-six. I had my heart set on your being the star lecturer. We thought we’d use a ‘literary heritage’ theme.”

“I’d be honored, Gresh, if I weren’t already booked for another journey.”

“Are you in much pain?”

“It comes and goes. It has a life of its own. I’ve named it the Gargoyle. Every day its grin stretches wider at my expense, but of course from its point of view, I’m the impediment. I’m the thing in the way of its development and growth.” She laughed weakly. “If it had a language, I wonder what it would name me.” Then she grimaced in obvious pain.

That was the sort of remark that made her the popular and compelling teacher she was. He wished he had more like her. She hadn’t come cheaply, of course, when he snared her five years ago. Better be glad she hadn’t followed up on the meteoric early brilliance of that first book, or he’d never have captured her for Aurelia. There’d been chapters of its successor, spread out between long–too long–intervals in the quarterlies, but not nearly enough to show for twenty-five years of scholarship from the precocious author of The Book of Hell: An Introduction to Visionary Mode. He still recalled how flattened with envy he had been, all those years ago back in Ann arbor, when her outrageous young triumph had flashed across the academic firmament. His own age and already published. And from the same university. (Though at least he had been in a different field: he was doing history and poly sci.) Not only published, but her picture in Time magazine. “The Dark Lady of Visions.” Her dissertation published before it had even been defended! Though later he’d heard that there had been some backlash by resentful professors that had delayed her degree for several years.

Her eyes were closed; she was focused on her pain. Her Gargoyle. An ovarian cancer that had gone too far. According to Ray Johnson, that champion disseminator of other people’s business, the word was that she’d flat out rejected chemo when that new Indian doctor Rainiwari, who could be somewhat blunt, told her what her chances were…or, rather, weren’t. “In that case,” she’d told Rainiwari, “I’d prefer to spend the time I have left studying for my Final Exam, rather than studying my disease.”

The president leaned forward and steadied himself with a hand on either of his charcoal-pinstriped knees. His first impulse had been to reach out and lay one of his hands on top of hers, which were clenched upon the blanket. But at present it seemed like an intrusion. The skin of Magda’s hands had acquired a glossy, yellowish sheen; whereas her formerly high-colored face had been dulled to a powdery gray pallor. These mysterious details of an individual’s dying: what would his own details be like?

He put his face nearer to hers. “We want to set up an endowed chair in your name,” he murmured, moved as much by the sorrowful huskiness that had crept appropriately into his announcement as by the magnanimous gift he offered.

The eyes opened. Dark, receptive pools, though ambushed by pain. Then the cracked corners of her mouth tipped upward in an irrepressible smirk. Why, she was expecting it, thought the president.

“The Magda Danvers Chair of Visionary Studies, we were thinking of calling it,” he continued. “I was talking to Ray Johnson. If we use the word ‘studies’ rather than ‘literature,’ we include the visual arts, which you’ve been doing all along anyway. It would leave things wide open for exciting linkups between departments. Our art chairman Sonia Wynkoop is having her Roman sabbatical, as you know, but I’m sure she’ll be amenable to the idea when she returns. Maybe we’d include music and science as well. Colleges that stay in business these days are getting away from the old departmental isolation. Everyone’s had their fill of the specialists, each keeping his acquirements to himself behind arcane jargons. The trend now is back to shared knowledge and cooperation. The Rounded Person.”

“A trend whose time has come none too soon, wouldn’t you say?” responded the smiling Magda, with a flash of that mocking insolence that many people, including President Gresham P. Harris, found disconcerting.

He rose, plucking at his trousers again to adjust their fall. “Well, you must rest. Keep up your strength for…for…” It was a rare occasion when he found himself at a loss for words.

“For my Final Exam,” Magda helped him out. She reached up for his hand with one of her waxy, yellow ones. The grip was weak but sure. The hand was dry, and hotter than he would have expected. “Thank you, Gresh. You’ve made me very happy about the chair.” She sounded like a mischievous little girl who’d gotten exactly what she wanted and was trying to be demure. But she closed her eyes again before he could attempt to read them.

Though he had semicommitments elsewhere, President Harris let himself be talked into having tea downstairs with Francis Lake because the poor guy looked exhausted and lonely and had obviously gone to trouble preparing it. They sat facing each other at a small table in a cozy corner of the living room where the afternoon sun played attractively on the fronds of healthy hanging plants in the deep-set windows and brought out the various patinas in the woods of some rather good Early American furniture. Boy, wouldn’t his wife Leora like to get her hands on that secretary.

Francis served him with attentive diffidence, making a little ceremony with all his paraphernalia: the strainer and the sugar tongs, the little silver pitcher of hot water. A soft-spoken, tranquil fellow, Magda Danver’s husband. Twelve years younger than she. The scuttlebutt was that, back in the sixties, Magda had stolen him out of a Catholic seminary somewhere up in the north of Michigan where she’d gone to lecture. He still had somewhat of the look of an aging choirboy. Now, that must have been an unusual courtship. But they seemed very contented in their domestic arrangement. Enviably so, his wife Leora believed. Once, at a faculty dinner party hosted by the president and his wife, Magda had made pointed innuendoes concerning their successful bed life.

“The forsythia will be out any day now,” said Francis Lake, slicing a cake with fruit on top and transferring a generous wedge to the president’s plate. “I saw some buds this morning that were about to pop.” He helped himself to a slice. “I hope she makes it to the lilac. Magda’s favorite is that deep purple lilac.” He motioned through the window at a very old lilac, whose convoluted branches were outlined in the liquid-yellow light of early spring.

“Let’s hope she does,” concurred the president. After a suitable pause, he added, “It’s going to be a big loss for all of us.”

“Yes,” replied Francis equably, still gazing out at the old lilac. What on earth will he do with himself when she’s gone? wondered the president. Ray Johnson said that Francis Lake had never even held a job. He’d been Magda’s house husband, just as some women (though that model was getting phased out rapidly now) were never anything but housewives. Francis would have her pension, of course. Which would have been considerably more if she’d died at sixty-five rather than fifty-eight.

Whereas we will save, thought the president. But, damn it, whom could he get for the Twenty-fifth Anniversary Cruise? Had to be someone of star quality. Of course there was Hugo Henry, Aurelia’s current novelist-in-residence, much more widely known than Magda, though not nearly as warm and engaging a speaker, his trusty spy Ray Johnson reported. Hugo was truculent; short men often were. Nevertheless, he could do the job. His reputation would carry him. And people like novelists, their creative aura. For the requisite bit of scholarly heft the president could get Stanforth from Columbia. Stanforth owed him several favors. But Hugo and his wife had had the disaster with their baby back in January and Alice hadn’t been seen outside the house since. It was probably still too soon to decently ask Hugo to do the cruise.

But the publicity over Magda’s endowed chair would be coming at a good time, for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first graduating class.

“I wonder, Francis, would you happen to have a recent photo of Magda in profile? We’ve got plans under way to raise some big bucks for a Magda Danvers chair, and I want to have her tintype on the letterhead we send out.”

“I was looking at some snapshots today. Does it have to be a profile?”

“Preferable. Profiles come out better on a tintype.”

Already Francis had sprung up from his chair and was rustling through a drawer of the secretary. He returned with a bulging envelope of snapshots, which he emptied out on the windowsill and began to sort through energetically, passing his selections across the table with accompanying commentaries. “That was in Paris, the summer Magda was doing her symbols of apotheosis research. It’s not very recent, but I think it’s still extremely like her, don’t you? Oh, no, here’s one. This is more recent, just before we came to Aurelia. Magda and I were accompanying the junior girls at Merrivale College on their semester abroad. I took this myself in Florence. You get a really good profile of Magda, though it’s slightly blurred, because she moved just as I clicked the shutter. She was pointing out to the girls where Dante lived…”

At this rate, I’ll be here all night, thought the president. But he took another sip of tea, surreptitiously glanced at his wristwatch, and let Francis go on a bit longer. The poor man’s face was animated with excitement and happiness. In his trip down memory lane (that old photo “still extremely like her”!), he had briefly forgotten the true state of affairs on the floor above.

Magda Danvers, the week before Christmas, returned home from surgery at Catskill Hospital and telephoned to her chairman she would not be meeting her classes for second semester. “It seems the Great Uncouth has taken up permanent residence inside me,” she informed him. “Well, I always was a good student; now I must see what I can learn from my final teacher.”

She had many visitors. This was during the first stage of her dying, when she still looked and spoke like her old self. Ray Johnson, the chairman of the English Department at Aurelia College, lost no time in disseminating her audacious remark around campus, and people wanted to go over to the restored Colonial farmhouse their prized teacher shared with her husband, Francis Lake, a devoted, self-effacing man much younger than herself, and see for themselves how Magda would go about learning from her final teacher.

During the remainder of deep winter, Magda held court in her snug upstairs study, crammed with all her books, surrounded by her beloved Blake reproductions. She reclined on the worn leather sofa in a baggy sweater and old tweed trousers and red velvet carpet slippers, an afghan spread over her, her famous mahogany hair floating loose around her shoulders rather than pinned up in its usual fat twist. A fire crackled in the small fireplace, tended by her husband. At regular intervals, Francis would poke his head around the door and ask, “How is the fire doing, my love?” If she replied, “We could use a couple more logs, Frannie,” that was their signal that she was enjoying her visitor, and Francis would slip in unobtrusively and rekindle the fire. If she said, “I think we’ll just let it burn itself out,” that meant the visitor was not contributing enough to the precious time she had left in this world, and Francis was to return in three to five minutes and announce it was time for one of Magda’s obligatory reset periods in the bedroom at the other end of the hall.

Her students came. Suzanne Riley brought Magda her map of the Mountain of Purgatory, Magda’s last class assignment before entering the hospital. “I want you to have the original of this, Professor Danvers. I mad a color photocopy to hand in to Professor Ramirez-Suarez. He’ll be taking your classes second semester while…until…” The girl looked away miserably.

“It’s okay, Suzanne,” Magda soothed her. “We both know what you mean. But this is a gorgeous map. All the detail you put into these figures. I didn’t even assign figures.”

“Well, I am an arts major. At first I dreaded your assignment. You know. All that extra work. I mean, if you’re going to draw a really good map, you have to read the stuff really carefully so you’ll know what to draw. But then it was weird. I got really involved. I always know when I get involved while I’m drawing because my mouth begins to water. If that doesn’t sound too gross.”

Francis Lake poked his head briefly around the door. “How’s the fire doing, Magda?”

“Oh, pile on some more logs,” replied Magda cheerfully. “But first, come and look at this splendid drawing. I want to get it framed as soon as possible and hang it up with my Blakes so I can look at it in the time I’ve got left. A good map of Purgatory fits in perfectly with my present studies. Let’s see, where am I on the Mountain? I’d like to be as far up as the Gluttonous cornice–the warm sins are better–but I’m probably still down in lower Purgatory with the cold and proud. Where do you think I am, Frannie?”

“You’re certainly not cold and proud,” said Francis. “It is a splendid map. I’ll take it down to the framers first thing in the morning, my love.”

First, my grandmother dies, and then my girlfriend breaks up with me, and now I’m losing my favorite teacher,” blubbered the young man, clutching at Magda’s afghan. “This has been the worst year of my life. I’m like, wondering what’s the point of living.” He covered his face with a corner of the afghan, managing to tug it off Magda’s knees in the process, and began to sob in earnest.

Francis Lake’s slim figure materialized at once in the doorway. “How’s the fire doing, Magda?”

“Oh, dying, like everything else in here,” said Magda. “Could you give Rick a Kleenex so he can blow his nose before he goes?”

Ramirez-Suarez paid courtly visits. “We miss you, bright lady. My task this semester is to make Paradise as interesting as Hell. You would have done a much better job with your marvelous viveza. I have been entertaining them a little by reading passages aloud in the Italian. Oh, and I have had to supplement the text with my own notes, which I pass out to them each session. Magda, these young people have no receptivity to allusions. They don’t know who Achilles was. They can’t name the seven deadly sins. Their biblical references are almost nil. Would you believe it, many of them weren’t familiar with the Sermon on the Mount.”

Her husband, smiling, stuck his head in the door.

“Ah, Francis, I have stayed too long and tired out our dearest Magda,” said the dapper little professor, leaping out of his chair.

“I’ll be tireder if you leave me, Tony. Frannie just came to heap more logs on our fire. And then you’ll have some tea with us. After you phoned this morning, Francis went out and bought those lemon squares you like.”

“Oh, dear lady–“

“Sit down, Tony. Haven’t you heard that invalids are always supposed to have their way? You know, I think we ought to propose a new course at Aurelia. A required course, and not just for the liberal-arts majors, either. The catalog description would describe it as ‘The very minimum of people, places, and things you’d better at lest have heard of if you plan to pass yourself off as an educated person.’ And we’d stuff it into them any old-fashioned way we could: forced memorization, pop quizzes, all the dirty old tricks. A two-semester course. We could call it Allusions One, and Allusions Two…”

The chairman of English, Ray Johnson, dropped by regularly, his shining eyes behind the round glasses taking in the minute details of her decline so he could report back to others.

“Tony Ramirez-Suarez said he found you in excellent spirits the other day. You two were cooking up some amusing new course?”

“Allusions One and Two,” said Magda. “ ‘Would you rather drink from the waters of Lethe, the Pierian Spring, or Parnassus’s Waters? Why?’ ‘What did Circe do to men?’ ‘Why did Diana keep to the woods?’ ‘List the seven deadly sins and the four cardinal virtues and the four levels of meaning.’ Just the basic stuff you need if you’re going to read a poem rather than a balance sheet.”

The chairman chuckled knowledgeably. Magda’s mind definitely hadn’t succumbed to the waters of Lethe yet, but her flamboyant dark red hair, he hadn’t failed to notice, now sprouted an untidy inch or more of dead white at the parting. This shocking sign of the arrogant Magda’s deterioration somewhat tempered his resentment of her for baiting him. He could get three out of four levels of meaning, but what the devil were the four cardinal virtues? Parnassus’s waters rang a faint bell from somewhere in his academic past, but what the hell did you get from drinking them?

He changed the subject. “Poor Alice and Hugo Henry. They lost their baby.”

“Oh, no! How?”

“He got tangled in the cord and the oxygen was cut off. Apparently it was going fine until the last minute, Hugo said. He seemed quite shaken when he came to school today. It was a home birth. That Dr. Romero all the mothers love and all the obstetricians hate.”

“Oh, poor lovely Alice. And she was so happy when I was with her at your party in early December. Oh, God, there we both were, laughing and talking together, her with her healthy baby inside her and me with my undiagnosed cancer inside me, both of us oblivious to our fates…”

Francis Lake appeared in the doorway.

“Francis, Alice and Hugo lost their baby.”

“When?”

“Last Thursday,” said Ray Johnson. “But we didn’t know about it until Monday, when Hugo came to meet his classes.” The chairman then repeated the sad details to Magda’s husband.

“Oh, I’m so upset of them,” wailed Magda, clutching at her hair. “Francis, I must write them a letter immediately.”

“After you’ve rested,” Francis told her sternly. “Ray, you won’t mind waiting here until I get Magda settled in her room. Then we’ll go downstairs and have some tea. If you can spare the time.”

“Oh, I can always spare the time for one of your famous teas,” said the chairman, laughing.

January’s calendar flipped over into February, then on into March. Gresham P. Harris, president of Aurelia College, mounted the stairs behind Magda’s husband.

“Last time, we went thataway,” remarked the president lightly when Francis, at the top of the stairs, turned right, not left toward Magda’s study with the nice fire burning.

“Magda is staying in bed today.”

“Oh, I see,” said the president, preparing himself not to show anything as he followed Francis Lake toward a room at the other end of the hallway.

“Magda, Magda,” was all he said, when he saw his brilliant star lying gray and docile under the blanket in the big four-poster bed. She was small, she who three months ago would have been described by her aficionados as “statuesque,” and by her enemies (for of course she had those, too) as overweight. Since his last visit to the house, she must have dropped twenty or thirty pounds. And the wiry white stuff bursting out of her scalp belonged to someone else. Some wild old woman…or man. The glossy dark red hair that had been distinctly hers, though everyone knew it came out of a package, still lay in straggles of its former glory on either side of her pillows. It had the look of having just been brushed out for his visit, probably by Francis Lake.

The president sat down in the chair Magda’s husband placed for him on the right side of the bed. Left alone in the room by Francis in the direct range of the dying woman’s penetrating gaze, he gained a few moments of respite by plucking at the knees of his perfectly creased trousers and surveying the neat lines of his black-stockinged ankles and thep9olished black wing-tip shoes below. He was a well-groomed, fastidious man who appeared younger than his fifty-eight years. He and Magda were the same age. Years ago, they had been graduate students at the same time in Ann Arbor, but they hadn’t known each other. These days he also gave his smooth, dark hair a little help from a package. College presidents were expected to look younger now.

I, too, could be struck by cancer and waste away in a few months, the president suddenly realized. His gaze meeting Magda’s snapping dark eyes at last, he had the distinct feeling that she had read his thought word for word. It made it easier for him to speak naturally.

“Well, Magda, this distresses me. I guess I was hoping for a miracle. Now that this Gulf War is over, I’ve rescheduled our Twenty-fifth Anniversary Alumni Cruise around the British Isles for August–our first cruise ever, to honor Aurelia’s first graduating class of sixty-six. I had my heart set on your being the star lecturer. We thought we’d use a ‘literary heritage’ theme.”

“I’d be honored, Gresh, if I weren’t already booked for another journey.”

“Are you in much pain?”

“It comes and goes. It has a life of its own. I’ve named it the Gargoyle. Every day its grin stretches wider at my expense, but of course from its point of view, I’m the impediment. I’m the thing in the way of its development and growth.” She laughed weakly. “If it had a language, I wonder what it would name me.” Then she grimaced in obvious pain.

That was the sort of remark that made her the popular and compelling teacher she was. He wished he had more like her. She hadn’t come cheaply, of course, when he snared her five years ago. Better be glad she hadn’t followed up on the meteoric early brilliance of that first book, or he’d never have captured her for Aurelia. There’d been chapters of its successor, spread out between long–too long–intervals in the quarterlies, but not nearly enough to show for twenty-five years of scholarship from the precocious author of The Book of Hell: An Introduction to Visionary Mode. He still recalled how flattened with envy he had been, all those years ago back in Ann arbor, when her outrageous young triumph had flashed across the academic firmament. His own age and already published. And from the same university. (Though at least he had been in a different field: he was doing history and poly sci.) Not only published, but her picture in Time magazine. “The Dark Lady of Visions.” Her dissertation published before it had even been defended! Though later he’d heard that there had been some backlash by resentful professors that had delayed her degree for several years.

Her eyes were closed; she was focused on her pain. Her Gargoyle. An ovarian cancer that had gone too far. According to Ray Johnson, that champion disseminator of other people’s business, the word was that she’d flat out rejected chemo when that new Indian doctor Rainiwari, who could be somewhat blunt, told her what her chances were…or, rather, weren’t. “In that case,” she’d told Rainiwari, “I’d prefer to spend the time I have left studying for my Final Exam, rather than studying my disease.”

The president leaned forward and steadied himself with a hand on either of his charcoal-pinstriped knees. His first impulse had been to reach out and lay one of his hands on top of hers, which were clenched upon the blanket. But at present it seemed like an intrusion. The skin of Magda’s hands had acquired a glossy, yellowish sheen; whereas her formerly high-colored face had been dulled to a powdery gray pallor. These mysterious details of an individual’s dying: what would his own details be like?

He put his face nearer to hers. “We want to set up an endowed chair in your name,” he murmured, moved as much by the sorrowful huskiness that had crept appropriately into his announcement as by the magnanimous gift he offered.

The eyes opened. Dark, receptive pools, though ambushed by pain. Then the cracked corners of her mouth tipped upward in an irrepressible smirk. Why, she was expecting it, thought the president.

“The Magda Danvers Chair of Visionary Studies, we were thinking of calling it,” he continued. “I was talking to Ray Johnson. If we use the word ‘studies’ rather than ‘literature,’ we include the visual arts, which you’ve been doing all along anyway. It would leave things wide open for exciting linkups between departments. Our art chairman Sonia Wynkoop is having her Roman sabbatical, as you know, but I’m sure she’ll be amenable to the idea when she returns. Maybe we’d include music and science as well. Colleges that stay in business these days are getting away from the old departmental isolation. Everyone’s had their fill of the specialists, each keeping his acquirements to himself behind arcane jargons. The trend now is back to shared knowledge and cooperation. The Rounded Person.”

“A trend whose time has come none too soon, wouldn’t you say?” responded the smiling Magda, with a flash of that mocking insolence that many people, including President Gresham P. Harris, found disconcerting.

He rose, plucking at his trousers again to adjust their fall. “Well, you must rest. Keep up your strength for…for…” It was a rare occasion when he found himself at a loss for words.

“For my Final Exam,” Magda helped him out. She reached up for his hand with one of her waxy, yellow ones. The grip was weak but sure. The hand was dry, and hotter than he would have expected. “Thank you, Gresh. You’ve made me very happy about the chair.” She sounded like a mischievous little girl who’d gotten exactly what she wanted and was trying to be demure. But she closed her eyes again before he could attempt to read them.

Though he had semicommitments elsewhere, President Harris let himself be talked into having tea downstairs with Francis Lake because the poor guy looked exhausted and lonely and had obviously gone to trouble preparing it. They sat facing each other at a small table in a cozy corner of the living room where the afternoon sun played attractively on the fronds of healthy hanging plants in the deep-set windows and brought out the various patinas in the woods of some rather good Early American furniture. Boy, wouldn’t his wife Leora like to get her hands on that secretary.

Francis served him with attentive diffidence, making a little ceremony with all his paraphernalia: the strainer and the sugar tongs, the little silver pitcher of hot water. A soft-spoken, tranquil fellow, Magda Danver’s husband. Twelve years younger than she. The scuttlebutt was that, back in the sixties, Magda had stolen him out of a Catholic seminary somewhere up in the north of Michigan where she’d gone to lecture. He still had somewhat of the look of an aging choirboy. Now, that must have been an unusual courtship. But they seemed very contented in their domestic arrangement. Enviably so, his wife Leora believed. Once, at a faculty dinner party hosted by the president and his wife, Magda had made pointed innuendoes concerning their successful bed life.

“The forsythia will be out any day now,” said Francis Lake, slicing a cake with fruit on top and transferring a generous wedge to the president’s plate. “I saw some buds this morning that were about to pop.” He helped himself to a slice. “I hope she makes it to the lilac. Magda’s favorite is that deep purple lilac.” He motioned through the window at a very old lilac, whose convoluted branches were outlined in the liquid-yellow light of early spring.

“Let’s hope she does,” concurred the president. After a suitable pause, he added, “It’s going to be a big loss for all of us.”

“Yes,” replied Francis equably, still gazing out at the old lilac. What on earth will he do with himself when she’s gone? wondered the president. Ray Johnson said that Francis Lake had never even held a job. He’d been Magda’s house husband, just as some women (though that model was getting phased out rapidly now) were never anything but housewives. Francis would have her pension, of course. Which would have been considerably more if she’d died at sixty-five rather than fifty-eight.

Whereas we will save, thought the president. But, damn it, whom could he get for the Twenty-fifth Anniversary Cruise? Had to be someone of star quality. Of course there was Hugo Henry, Aurelia’s current novelist-in-residence, much more widely known than Magda, though not nearly as warm and engaging a speaker, his trusty spy Ray Johnson reported. Hugo was truculent; short men often were. Nevertheless, he could do the job. His reputation would carry him. And people like novelists, their creative aura. For the requisite bit of scholarly heft the president could get Stanforth from Columbia. Stanforth owed him several favors. But Hugo and his wife had had the disaster with their baby back in January and Alice hadn’t been seen outside the house since. It was probably still too soon to decently ask Hugo to do the cruise.

But the publicity over Magda’s endowed chair would be coming at a good time, for the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first graduating class.

“I wonder, Francis, would you happen to have a recent photo of Magda in profile? We’ve got plans under way to raise some big bucks for a Magda Danvers chair, and I want to have her tintype on the letterhead we send out.”

“I was looking at some snapshots today. Does it have to be a profile?”

“Preferable. Profiles come out better on a tintype.”

Already Francis had sprung up from his chair and was rustling through a drawer of the secretary. He returned with a bulging envelope of snapshots, which he emptied out on the windowsill and began to sort through energetically, passing his selections across the table with accompanying commentaries. “That was in Paris, the summer Magda was doing her symbols of apotheosis research. It’s not very recent, but I think it’s still extremely like her, don’t you? Oh, no, here’s one. This is more recent, just before we came to Aurelia. Magda and I were accompanying the junior girls at Merrivale College on their semester abroad. I took this myself in Florence. You get a really good profile of Magda, though it’s slightly blurred, because she moved just as I clicked the shutter. She was pointing out to the girls where Dante lived…”

At this rate, I’ll be here all night, thought the president. But he took another sip of tea, surreptitiously glanced at his wristwatch, and let Francis go on a bit longer. The poor man’s face was animated with excitement and happiness. In his trip down memory lane (that old photo “still extremely like her”!), he had briefly forgotten the true state of affairs on the floor above.

Textul de pe ultima copertă

"Mates are not always matches, and matches are not always mates," pronounces Magda Danvers, the magnificent central figure in Gail Godwin's wise and affecting new novel. With The Good Husband, one of America's most gifted novelists creates a portrait of two marriages and four unforgettable characters that travels beyond the usual questions of love and domestic comfort to explore the most profound consequences of intimate relationships. It is also, in its deepest sense, a novel about how we influence and transform - and sometimes complete - one another. As a young woman, brilliant, charismatic, and eternally curious, Marsha Danziger transformed herself into Magda Danvers, taking the academic world by storm with her controversial treatise on visionaries, The Book of Hell. She was already a star when she came upon Francis Lake in a midwestern seminary and married him, to everyone's surprise, including their own. It was a mating that seemed perfect: Magda pursued her career, and attentive, caring Francis devoted himself to Magda. Now, Magda's grave illness puts their marriage to its ultimate test. Even as she faces her "Final Examination," Magda's genius does not desert her. From her bed she continues to arouse her visitors with compelling thoughts and questions, which will change the lives of some of them. Into the heady atmosphere of Magda's provocative repartee comes Alice Henry, fresh from her own family tragedy. Magda's room soon becomes a refuge for Alice from her crumbling marriage to brooding Southern novelist Hugo Henry. But is it the incandescence of Magda's ideas that draws Alice, or the secret of "the good marriage" that she is desperate to discover? For Alice, Hugo, Francis, and Magda will learn that the most ideal relationship - even a perfect marriage - doesn't come without a price. Gracefully written, keenly insightful, intimate in its revelations, The Good Husband reverberates with the lives of its characters, their histories, and the most urgent longings of their hearts - a triumph of the novelist's art, from the author of A Mother and Two Daughters, The Finishing School, A Southern Family, and Father Melancholy's Daughter, all of which were New York Times bestsellers.

Notă biografică

Gail Godwin is a three-time National Book Award finalist and the bestselling author of twelve critically acclaimed novels, including A Mother and Two Daughters, Violet Clay, Father Melancholy’s Daughter, Evensong, The Good Husband, Queen of the Underworld, and Unfinished Desires. She is also the author of The Making of a Writer: Journals, 1961–1963 and The Making of a Writer, Volume 2: Journals, 1963–1969, edited by Rob Neufeld. She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts grants for both fiction and libretto writing, and the Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She has written libretti for ten musical works with the composer Robert Starer. Gail Godwin lives in Woodstock, New York.