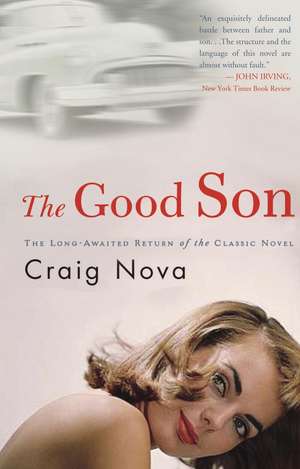

The Good Son

Autor Craig Novaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2005

Chip Mackinnon returns from World War II a changed man. After being shot down over the desert and imprisoned by the enemy, the world of privilege to which he belongs seems shallow. But in the shadow of his older brother’s death, the full weight of his father’s expectations falls on Chip. Pop Mackinnon—whose money is new but just as good as anyone else’s—has designs on the upper echelons of society. The polo ponies and expensive education he bought for his son weren’t gifts; they were an investment in the family’s future. Now it’s time for Chip to pay him back by marrying a girl who can finally bring the Mackinnons into society’s inner circle.

A shrewd and cunning man, Pop is used to getting his way—until the arrival of Jean Cooper, that is. This Midwestern beauty awakens Chip’s passions, and the two embark on an affair that threatens to destroy Pop’s social-climbing plans. A battle of wills between father and son ensues, one that tests the boundaries of their relationship and strays into the place where love turns irrevocably to hate.

Originally published in 1982 to wide acclaim, The Good Son remains Craig Nova’s undisputed masterpiece. This classic of contemporary American literature artfully explores the complicated web of emotions that exists between fathers and sons—ambition, jealousy, loyalty, love—in a tale that compels with its simple, searing honesty.

Also Available as an eBook.

Preț: 108.01 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 162

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.67€ • 21.66$ • 17.09£

20.67€ • 21.66$ • 17.09£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307236975

ISBN-10: 0307236978

Pagini: 456

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:Pbk.

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307236978

Pagini: 456

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:Pbk.

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Craig Nova is the award-winning author of ten novels. He lives in Putney, Vermont.

Extras

Chip Mackinnon

North Africa. 1942

My father is a coarse, charming man, a lawyer, and a good one, and when I was flying over the desert and the German pursuit pilot began pouring round after round into my plane (a P-40), I was thinking of how I learned to drive, and how it affected my father. The desert sky was beautiful, the bleached color you sometimes see in blue glass that has rolled up on the beach. There were pillars of smoke here and there and some fires, too, which were made pale by the sun. If I had been shooting down the German, I imagine I would have been just as zealous. I wonder what kind of car he learned to drive, a Mercedes or Dusenberg perhaps: I learned to drive a Buick.

My father's chauffeur was named Wade, and although it took a while, we became friends and went to the movies together. I liked Wade for a number of reasons, not the least of which was a sense of mystery about him. When I was young I was impressed by the knowledge that Wade had been in prison (in Wyoming), but when I got a little older I realized it wasn't the prison that made him mysterious so much as an un-named, but finally discovered regret. He understood regret. After we became friends we started going to the movie theater in a small town near where my father owns a piece of land on the Delaware River (a piece of which land and a house built for my dead brother I now own). The theater was not very large and the seats were shaggy with stuffing and sometimes Wade and I would be the only people there, staring at that screen which had a hole in the upper right hand part. The hole looked like a bat.

Wade was thirty-five when he started to work for my father, and he was a tall, thin man, with a long nose and chin, pale, tea-colored eyes. He favored a dark green sweater worn over an undershirt when he wasn't working. At other times he wore the blue trousers and jacket my father required of him. On weekends, when I was home from school, Wade drove my father and me to that land on the Delaware. Wade was a little nervous, but this was not unusual, considering the man for whom he had to work.

I like to think of the land as it is in the fall, when the leaves are gone and you can see the woods, the fieldstone that projects from the ground like the prows of speedboats, the greenish park-statue color of the lichen. We drove along the Delaware for a while and then turned where the Mongaup River passed under the highway. The ground was scaled with leaves of red and brown. We climbed a road that went through the trees and finally stopped in front of a two story clapboard house that had shutters which were painted black. There was a front porch and an elm tree before it and my father used to like to sit on the front porch and drink a mint julep. There's a new road on the land now, one that's a little straighter and doesn't wash out so easily. My father made it himself with a bulldozer he bought as army surplus. The machine was a bargain and it was still painted green. There are both cow and sheep barns, although there is no silo. The cow barn has been made into a garage with an apartment (where Wade stayed) and another outbuilding has been fixed too so that the housekeeper and her husband had their privacy.

I learned to drive in 1936 and the car was a Buick, a new one. It was black and had comfortable seats covered with a fuzzy material. The Buick had a three-speed transmission with the gearshift on the floor. The starter was on the floor, too. The paint was waxed and kept pretty much spotless, and the car had whitewall tires. Usually, when my father and I got into the backseat, after having come from the apartment in New York (in which there was an imitation Mexican garden, complete with terra-cotta tiles), my father said, "Wade, now we'll begin the process of drinking and driving, slowly along." He made Wade stop at every bar on the road, where my father drank quickly and alone. About halfway to the farm he started smoking cigars (actually you could call them "seegars" because that's what they smelled like, and he wouldn't have the windows open, either). My father enjoyed the odor. I didn't, though, and just like clockwork, about three quarters of the way to the farm, I'd get sick. These trips were usually made at night, on Friday, and my father and I sat together in the backseat. My father bore a striking resemblance to W. C. Fields, although I don't think my father was as funny. In any case, in the spring before I learned to drive, I can remember sitting in the backseat beside my father, watching his bean-bag nose, his profile against the passing lights of other cars. I began to squirm. The backseat was filled with smoke. "Wade," said my father, flicking an ash onto the floor, "Wade, stop the car. The boy's going to puke."

Wade stopped the Buick. Usually, I was able to get out of the backseat myself, but there were times when I was already gagging, and then my father opened the door, held the cigar in one hand, and helped me into the gutter or drainage ditch at the side of the road. My father enjoyed his cigar while I vomited. One night, just before I decided to learn how to drive, I was kneeling in the drainage ditch and I looked up and saw the Buick against the passing lights, saw its monstrous, high, silky shape, and the open back door, out of which came the bluish smoke of the cigar. My father didn't look at me, and Wade didn't either. Wade was a polite man. On this particular night, when I could see that phantom of the Buick, when I could taste the bile and acid while I was kneeling in the ditch (I think it was filled with some daisies and Queen Anne's lace: there was some gentle, lingering odor there), my father said, "You done?" I shook my head and heaved again, and then I climbed into the back of the car, the skunky odor there. My father must have paid a fortune for those cigars, too: he said they were made by blind men in Cuba, and I guess this was true, because the men who made them didn't always know what they were putting inside. I sat next to my father and he reached over and closed the door.

"Stop at the next bar, Wade," he said, his voice thumping like a drum, even though he wasn't that big, really. "I need a drink."

I can still name, in order, those roadhouses and taverns and saloons where my father stopped to drink. Wade and I sat in the Buick.

"How's school?" said Wade.

"Good," I said, still tasting the sour vomit.

"That's good," said Wade. "Education is what you need."

"Yes," I said.

A few years before, when Wade began to work for my father, our conversations stopped here, but after a month or so, Wade said, "Do you mind if I ask you a question?" and I said, "No," and he said, "What the hell was the Battle of Hastings?" I gave him my schoolboy's knowledge, and he nodded with a sincere reverence. There were words and phrases, events, things that he heard in conversation or saw in the paper, and he didn't know where to go to find out about them, and he had been ashamed to ask anyone his own age. So after we went through the Battle of Hastings in the parking lot, we moved onto other subjects, although I'm sure I failed him on many occasions, since I really didn't have much to say about the Manichaean Heresy, the Papacy at Avignon, the Boxer Rebellion (it is a small triumph, however, that Wade understands that the Boxer Rebellion had nothing to do with Madison Square Garden). I did give a fair account of quadratic equations, geology, Mount Everest, and Middle English (of which I recited a few lines, "The Wife of Bath"). After I had given it, Wade said, "Chip, you wouldn't put me on, would you? You wouldn't pull Wade's leg, now? Because that doesn't sound like English at all. That sounds like the talk of, you know, someone who's taken leave of his senses." "No," I said, "I'm not fooling you. Maybe it's my accent." Geography was our great triumph, and we played a game with it. I'd say "America," which ends in "A," and then Wade would have to say "Alaska," and then I'd have to say "Amsterdam," and then he'd have to say "Manchuria." Wade loved this game, and we'd play it when we sat in the parking lots while my father filled his gut with bourbon.

It was after we first played this game that Wade suggested we go to the movies in a small town near the farm. He had lost, being caught by St. Croix, not knowing of the existence of X Rock, Antarctica; Xenia, Ohio; or the Xie River; but he was not ashamed, and I was fairly sure he was in the market for a National Geographic Atlas, if only for the index. He suggested we go the next night, and we did, with me still in the backseat of the Buick and Wade driving. After we had seen our first movie, I sat up front, and we weren't so awkward anymore. We saw many movies. Wade sat next to me in the dark, with a box of stale popcorn and a bottle of cheap liquor in a paper bag, his eyes set on the screen. He couldn't stand missing a minute, not one frame, although if the picture were very bad, he didn't mind if I went to the lobby and read the day-old paper that was there. The seats in the theater were usually ankle-deep in trash, popcorn boxes, and candy bar wrappers, and Wade smoked his cigarettes in the middle of the movie, or continuously when he wasn't eating the popcorn or sipping from the bottle in the bag. He started a fire one night, and the manager had to put it out with a fire extinguisher that made a whitish foam. Wade apologized for starting the fire, but then stepped over the row of seats in front of us with his long legs, sat down, and continued to watch. The manager wanted to throw him out, but then he saw me, and knew that my father had a new chauffeur, and thought the better of it. My father made quite substantial political contributions and everyone wanted to run for the town's only salaried (and otherwise lucrative) job, that of superintendent of roads.

Wade and I went to the movies whenever we could, and we saw some terrible ones, which troubled me, if only because they didn't trouble Wade. It was not a matter of entertainment for Wade, or so it seemed. During the particularly bad ones I no longer went to the lobby and looked at the old paper, but instead watched Wade, his eyes set on the screen, his papered bottle rising and falling, his hands lighting the cigarettes and dropping the still burning matches. In those days I favored pirate films, with lots of swinging from ropes. One night there was a historical epic. In it there was a scene in a Middle Eastern harem, which had twenty-five or so women dressed in spangled tops and sultan's trousers (tight at the ankle). Wade's eyes were wide and unblinking but he stopped the bottle halfway to his lips and dropped the box of popcorn. He stared at a small, dark, attractive woman who was lounging before some man with a headdress. She looked quite appealing. Then the scene changed and Wade went back to sipping the bottle, although he didn't pick up the popcorn. After the film was over, and we were back in the car, Wade said, "Chip, that was a good film." I didn't say anything, and I forgot about the dark woman with the small lips. She turned up again, though, in a western, and Wade watched her carefully. After she left the screen, Wade took a hard pull from the bottle. He looked at me, and saw my curious expression, but we didn't speak about it. Now I never went to read the papers and could not have been dragged from the theater, since I was also looking for the "extra," that dark, taut woman with the small lips and who had above one eye a slight distortion that might have been caused by a scar. It gave her face that slight asymmetry, the touch of the freakish, which makes a woman beautiful rather than pretty. I was looking for her if only to discover the reason she had such an effect on Wade. The closest we ever came to speaking about the woman was the one time I said, "Look. It says here a cast of thousands. That looks good, doesn't it?" Wade said "Yes" and went to the liquor store to buy a bottle in a sack.

On the night I decided to learn to drive, Wade and I sat for a while in the parking lot of a roadhouse and then Wade turned in his seat and said "Morocco?" (which isn't too far from where the German pursuit pilot came up on my tail and began putting round after round into my P-40) and I said "Orinoco" and he said "Oregon" and then my father came out of the bar, his mood not much improved by the bourbon.

We continued until we came to my father's favorite part of the road, a piece about two miles long: it was cut into a cliff above the Delaware. The road wasn't much to speak of. Straight up on one side, straight down on the other, and it was crooked, filled with sharp turns, because the cliff wasn't smooth. There were a couple of guardrails, old ones made of planks that wouldn't stop a man on a bicycle, at the places where the road turned toward the precipice and the river below. One of these guardrails looked like a broken clotheshorse: a drunken policeman had gone through it while chasing a speeder.

When we came to this section of road Wade began to twist in his seat and finally my father said, "Wade, stop the car. I'll take it through the turns. You get in the back with the boy."

Wade stopped the Buick. You could see the beginning of the cliff ahead, the receding and twisting road much farther on: it was as though the first turn were a sound, a shout, and the other turns echoes of the first. Wade got out of the car and peered down at the river, which could be seen well from where he stood, although his perspective was more like one you'd have if you were looking at the river from an airplane. You could see the silken and roily water through the mist that was just above the surface. Wade stared at it, and got into the backseat.

North Africa. 1942

My father is a coarse, charming man, a lawyer, and a good one, and when I was flying over the desert and the German pursuit pilot began pouring round after round into my plane (a P-40), I was thinking of how I learned to drive, and how it affected my father. The desert sky was beautiful, the bleached color you sometimes see in blue glass that has rolled up on the beach. There were pillars of smoke here and there and some fires, too, which were made pale by the sun. If I had been shooting down the German, I imagine I would have been just as zealous. I wonder what kind of car he learned to drive, a Mercedes or Dusenberg perhaps: I learned to drive a Buick.

My father's chauffeur was named Wade, and although it took a while, we became friends and went to the movies together. I liked Wade for a number of reasons, not the least of which was a sense of mystery about him. When I was young I was impressed by the knowledge that Wade had been in prison (in Wyoming), but when I got a little older I realized it wasn't the prison that made him mysterious so much as an un-named, but finally discovered regret. He understood regret. After we became friends we started going to the movie theater in a small town near where my father owns a piece of land on the Delaware River (a piece of which land and a house built for my dead brother I now own). The theater was not very large and the seats were shaggy with stuffing and sometimes Wade and I would be the only people there, staring at that screen which had a hole in the upper right hand part. The hole looked like a bat.

Wade was thirty-five when he started to work for my father, and he was a tall, thin man, with a long nose and chin, pale, tea-colored eyes. He favored a dark green sweater worn over an undershirt when he wasn't working. At other times he wore the blue trousers and jacket my father required of him. On weekends, when I was home from school, Wade drove my father and me to that land on the Delaware. Wade was a little nervous, but this was not unusual, considering the man for whom he had to work.

I like to think of the land as it is in the fall, when the leaves are gone and you can see the woods, the fieldstone that projects from the ground like the prows of speedboats, the greenish park-statue color of the lichen. We drove along the Delaware for a while and then turned where the Mongaup River passed under the highway. The ground was scaled with leaves of red and brown. We climbed a road that went through the trees and finally stopped in front of a two story clapboard house that had shutters which were painted black. There was a front porch and an elm tree before it and my father used to like to sit on the front porch and drink a mint julep. There's a new road on the land now, one that's a little straighter and doesn't wash out so easily. My father made it himself with a bulldozer he bought as army surplus. The machine was a bargain and it was still painted green. There are both cow and sheep barns, although there is no silo. The cow barn has been made into a garage with an apartment (where Wade stayed) and another outbuilding has been fixed too so that the housekeeper and her husband had their privacy.

I learned to drive in 1936 and the car was a Buick, a new one. It was black and had comfortable seats covered with a fuzzy material. The Buick had a three-speed transmission with the gearshift on the floor. The starter was on the floor, too. The paint was waxed and kept pretty much spotless, and the car had whitewall tires. Usually, when my father and I got into the backseat, after having come from the apartment in New York (in which there was an imitation Mexican garden, complete with terra-cotta tiles), my father said, "Wade, now we'll begin the process of drinking and driving, slowly along." He made Wade stop at every bar on the road, where my father drank quickly and alone. About halfway to the farm he started smoking cigars (actually you could call them "seegars" because that's what they smelled like, and he wouldn't have the windows open, either). My father enjoyed the odor. I didn't, though, and just like clockwork, about three quarters of the way to the farm, I'd get sick. These trips were usually made at night, on Friday, and my father and I sat together in the backseat. My father bore a striking resemblance to W. C. Fields, although I don't think my father was as funny. In any case, in the spring before I learned to drive, I can remember sitting in the backseat beside my father, watching his bean-bag nose, his profile against the passing lights of other cars. I began to squirm. The backseat was filled with smoke. "Wade," said my father, flicking an ash onto the floor, "Wade, stop the car. The boy's going to puke."

Wade stopped the Buick. Usually, I was able to get out of the backseat myself, but there were times when I was already gagging, and then my father opened the door, held the cigar in one hand, and helped me into the gutter or drainage ditch at the side of the road. My father enjoyed his cigar while I vomited. One night, just before I decided to learn how to drive, I was kneeling in the drainage ditch and I looked up and saw the Buick against the passing lights, saw its monstrous, high, silky shape, and the open back door, out of which came the bluish smoke of the cigar. My father didn't look at me, and Wade didn't either. Wade was a polite man. On this particular night, when I could see that phantom of the Buick, when I could taste the bile and acid while I was kneeling in the ditch (I think it was filled with some daisies and Queen Anne's lace: there was some gentle, lingering odor there), my father said, "You done?" I shook my head and heaved again, and then I climbed into the back of the car, the skunky odor there. My father must have paid a fortune for those cigars, too: he said they were made by blind men in Cuba, and I guess this was true, because the men who made them didn't always know what they were putting inside. I sat next to my father and he reached over and closed the door.

"Stop at the next bar, Wade," he said, his voice thumping like a drum, even though he wasn't that big, really. "I need a drink."

I can still name, in order, those roadhouses and taverns and saloons where my father stopped to drink. Wade and I sat in the Buick.

"How's school?" said Wade.

"Good," I said, still tasting the sour vomit.

"That's good," said Wade. "Education is what you need."

"Yes," I said.

A few years before, when Wade began to work for my father, our conversations stopped here, but after a month or so, Wade said, "Do you mind if I ask you a question?" and I said, "No," and he said, "What the hell was the Battle of Hastings?" I gave him my schoolboy's knowledge, and he nodded with a sincere reverence. There were words and phrases, events, things that he heard in conversation or saw in the paper, and he didn't know where to go to find out about them, and he had been ashamed to ask anyone his own age. So after we went through the Battle of Hastings in the parking lot, we moved onto other subjects, although I'm sure I failed him on many occasions, since I really didn't have much to say about the Manichaean Heresy, the Papacy at Avignon, the Boxer Rebellion (it is a small triumph, however, that Wade understands that the Boxer Rebellion had nothing to do with Madison Square Garden). I did give a fair account of quadratic equations, geology, Mount Everest, and Middle English (of which I recited a few lines, "The Wife of Bath"). After I had given it, Wade said, "Chip, you wouldn't put me on, would you? You wouldn't pull Wade's leg, now? Because that doesn't sound like English at all. That sounds like the talk of, you know, someone who's taken leave of his senses." "No," I said, "I'm not fooling you. Maybe it's my accent." Geography was our great triumph, and we played a game with it. I'd say "America," which ends in "A," and then Wade would have to say "Alaska," and then I'd have to say "Amsterdam," and then he'd have to say "Manchuria." Wade loved this game, and we'd play it when we sat in the parking lots while my father filled his gut with bourbon.

It was after we first played this game that Wade suggested we go to the movies in a small town near the farm. He had lost, being caught by St. Croix, not knowing of the existence of X Rock, Antarctica; Xenia, Ohio; or the Xie River; but he was not ashamed, and I was fairly sure he was in the market for a National Geographic Atlas, if only for the index. He suggested we go the next night, and we did, with me still in the backseat of the Buick and Wade driving. After we had seen our first movie, I sat up front, and we weren't so awkward anymore. We saw many movies. Wade sat next to me in the dark, with a box of stale popcorn and a bottle of cheap liquor in a paper bag, his eyes set on the screen. He couldn't stand missing a minute, not one frame, although if the picture were very bad, he didn't mind if I went to the lobby and read the day-old paper that was there. The seats in the theater were usually ankle-deep in trash, popcorn boxes, and candy bar wrappers, and Wade smoked his cigarettes in the middle of the movie, or continuously when he wasn't eating the popcorn or sipping from the bottle in the bag. He started a fire one night, and the manager had to put it out with a fire extinguisher that made a whitish foam. Wade apologized for starting the fire, but then stepped over the row of seats in front of us with his long legs, sat down, and continued to watch. The manager wanted to throw him out, but then he saw me, and knew that my father had a new chauffeur, and thought the better of it. My father made quite substantial political contributions and everyone wanted to run for the town's only salaried (and otherwise lucrative) job, that of superintendent of roads.

Wade and I went to the movies whenever we could, and we saw some terrible ones, which troubled me, if only because they didn't trouble Wade. It was not a matter of entertainment for Wade, or so it seemed. During the particularly bad ones I no longer went to the lobby and looked at the old paper, but instead watched Wade, his eyes set on the screen, his papered bottle rising and falling, his hands lighting the cigarettes and dropping the still burning matches. In those days I favored pirate films, with lots of swinging from ropes. One night there was a historical epic. In it there was a scene in a Middle Eastern harem, which had twenty-five or so women dressed in spangled tops and sultan's trousers (tight at the ankle). Wade's eyes were wide and unblinking but he stopped the bottle halfway to his lips and dropped the box of popcorn. He stared at a small, dark, attractive woman who was lounging before some man with a headdress. She looked quite appealing. Then the scene changed and Wade went back to sipping the bottle, although he didn't pick up the popcorn. After the film was over, and we were back in the car, Wade said, "Chip, that was a good film." I didn't say anything, and I forgot about the dark woman with the small lips. She turned up again, though, in a western, and Wade watched her carefully. After she left the screen, Wade took a hard pull from the bottle. He looked at me, and saw my curious expression, but we didn't speak about it. Now I never went to read the papers and could not have been dragged from the theater, since I was also looking for the "extra," that dark, taut woman with the small lips and who had above one eye a slight distortion that might have been caused by a scar. It gave her face that slight asymmetry, the touch of the freakish, which makes a woman beautiful rather than pretty. I was looking for her if only to discover the reason she had such an effect on Wade. The closest we ever came to speaking about the woman was the one time I said, "Look. It says here a cast of thousands. That looks good, doesn't it?" Wade said "Yes" and went to the liquor store to buy a bottle in a sack.

On the night I decided to learn to drive, Wade and I sat for a while in the parking lot of a roadhouse and then Wade turned in his seat and said "Morocco?" (which isn't too far from where the German pursuit pilot came up on my tail and began putting round after round into my P-40) and I said "Orinoco" and he said "Oregon" and then my father came out of the bar, his mood not much improved by the bourbon.

We continued until we came to my father's favorite part of the road, a piece about two miles long: it was cut into a cliff above the Delaware. The road wasn't much to speak of. Straight up on one side, straight down on the other, and it was crooked, filled with sharp turns, because the cliff wasn't smooth. There were a couple of guardrails, old ones made of planks that wouldn't stop a man on a bicycle, at the places where the road turned toward the precipice and the river below. One of these guardrails looked like a broken clotheshorse: a drunken policeman had gone through it while chasing a speeder.

When we came to this section of road Wade began to twist in his seat and finally my father said, "Wade, stop the car. I'll take it through the turns. You get in the back with the boy."

Wade stopped the Buick. You could see the beginning of the cliff ahead, the receding and twisting road much farther on: it was as though the first turn were a sound, a shout, and the other turns echoes of the first. Wade got out of the car and peered down at the river, which could be seen well from where he stood, although his perspective was more like one you'd have if you were looking at the river from an airplane. You could see the silken and roily water through the mist that was just above the surface. Wade stared at it, and got into the backseat.

Recenzii

“An exquisitely delineated battle between father and son . . . The structure and the language of this novel are almost without fault.” —John Irving, New York Times Book Review

“[Nova’s fiction] is so powerful, so alive, it is a wonder that turning its pages doesn’t somehow burn one’s hands.” —New York Times

“Nova’s novels deserve to be ranked among the best fiction of the past two decades.” —Washington Post

“[Nova’s fiction] is so powerful, so alive, it is a wonder that turning its pages doesn’t somehow burn one’s hands.” —New York Times

“Nova’s novels deserve to be ranked among the best fiction of the past two decades.” —Washington Post

Descriere

Originally published in 1982, this highly acclaimed novel explores the forces that unite and divide fathers and sons in a classic tale of ambition, loyalty, and love.