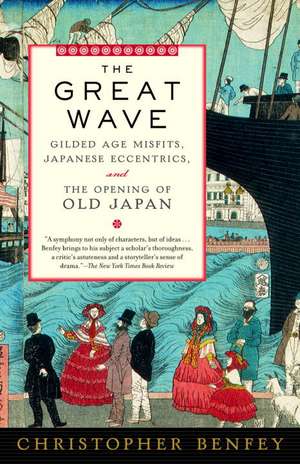

The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan

Autor Christopher E. G. Benfey, Christopher Benfeyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2004

In The Great Wave, Benfey tells the story of the tightly knit group of nineteenth-century travelers—connoisseurs, collectors, and scientists—who dedicated themselves to exploring and preserving Old Japan. As Benfey writes, “A sense of urgency impelled them, for they were convinced—Darwinians that they were—that their quarry was on the verge of extinction.”

These travelers include Herman Melville, whose Pequod is “shadowed by hostile and mysterious Japan”; the historian Henry Adams and the artist John La Farge, who go to Japan on an art-collecting trip and find exotic adventures; Lafcadio Hearn, who marries a samurai’s daughter and becomes Japan’s preeminent spokesman in the West; Mabel Loomis Todd, the first woman to climb Mt. Fuji; Edward Sylvester Morse, who becomes the world’s leading expert on both Japanese marine life and Japanese architecture; the astronomer Percival Lowell, who spends ten years in the East and writes seminal works on Japanese culture before turning his restless attention to life on Mars; and President (and judo enthusiast) Theodore Roosevelt. As well, we learn of famous Easterners come West, including Kakuzo Okakura, whose The Book of Tea became a cult favorite, and Shuzo Kuki, a leading philosopher of his time, who studied with Heidegger and tutored Sartre.

Finally, as Benfey writes, his meditation on cultural identity “seeks to capture a shared mood in both the Gilded Age and the Meiji Era, amid superficial promise and prosperity, of an overmastering sense of precariousness and impending peril.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 133.39 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.53€ • 27.74$ • 21.46£

25.53€ • 27.74$ • 21.46£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375754555

ISBN-10: 0375754555

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0375754555

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Christopher Benfey teaches literature at Mount Holyoke College, where he is co-director of the Weissman Center for Leadership. Benfey is the author of Emily Dickinson and the Problem of Others, The Double Life of Stephen Crane, and Degas in New Orleans. He lives in Amherst, Massachusetts, with his wife and two sons.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

THE FLOATING WORLD

If that double-bolted land, Japan, is ever

to become hospitable, it is the whale-ship alone

to whom the credit will be due;

for already she is on the threshold.

-herman melville, moby-dick (1851)

Imagine the following scenario. Two fatherless boys on opposite sides of the earth take to the sea within days of each other, in search of adventure and a livelihood. Their paths cross on an archipelago in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, where they encounter some of the same helpers, and hinderers. One arrives after years of wandering at the other's port of departure. The other falls just short but writes an extraordinary book that completes the journey. One deserts a whaling ship while the other is rescued by one. One discovers the joys of savage life while the other discovers the ambiguous joys of civilization. Each dreams of "opening" the other's country, and each is changed utterly in the process; their reward is gloom and isolation. Now, let us give these lost boys and Pacific drifters names and dates.

I. The May Basket

During the waning hours of a warm spring evening in 1843, in the coastal

village of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, sixteen-year-old John Mung hung a May basket on the knocker of his classmate Catherine Terry's door. A note was hidden among the buttercups:

Tis in the chilly night

A basket you've got hung.

Get up, strike a light!

And see me run

But no take chase me.

Mung, according to age-old New England custom, ran off into the enveloping night-anonymous except for that telltale fifth line. Catherine Terry had reason to believe that the basket was "hung" by none other than John Mung, whom on occasion she had smiled at demurely during recess.

One Sunday morning, during that same spring of 1843, John Mung sat in Captain Whitfield's pew in the Fairhaven Congregational Church. After the service one of the elders of the church approached Captain Whitfield and quietly suggested that Mung should sit in the section reserved for escaped slaves. Mung was distracting the other worshipers, the elder explained, and would be more at home among the Negroes in the balcony.

Two years earlier John Mung had no idea that the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, existed. He had never heard of the United States or of the English language. Rituals such as May baskets and the Christian Mass would have seemed to him impossibly foreign, and remote. In fact, no one by the name of John Mung existed in 1841. Call him Manjiro instead.

On January 5, 1841, in the Year of the Ox, the boy Manjiro, fourteen years old, boarded a boat with four other fishermen on the coast of Shikoku, the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. Manjiro, who lived with his mother in the tiny village of Nakanohama, had wandered up the coast in search of work. Captain Fudenjo of the village of Usa, near Tosa, had found Manjiro asleep on the sand and asked him to join his crew: his two brothers, Jusuke and Goemon, and another fisherman called Toraemon. In the fixed feudal order of Old Japan, peasants like Manjiro had only one name, and one life to look forward to. Like his father, who died when Manjiro was nine, and his grandfather and great-grandfather back into the mists of time, Manjiro would be a fisherman. What knocked him loose from this order established across millennia was a storm-the "great wind" called the typhoon.

Fudenjo's twenty-four-foot boat with a square sail, like all boats made in Japan, was equipped to hug the shore-to go farther out was strictly against the national laws and punishable by death. The nets came up empty for two days. On the third the crew suddenly found themselves in a school of mackerel. In their excitement they barely noticed that the wind-whipped waves had risen. They tugged hurriedly at the heavily laden nets, but by the time they had retrieved them the storm was in full force. Their efforts to gain control of the boat led to disaster; the sails were torn and the rudder split in two. Tempest-tossed, they watched helplessly as they drifted farther and farther out to sea. The next morning the color of the sea, dark indigo, confirmed their worst fears. They were caught in the Kuroshio, or Black Current, a Pacific counterpart of the Gulf Stream. The best they could hope for was an island in their path. For these five superstitious and illiterate men, the sea was boundless-until somewhere, without warning, one dropped off the edge. Through eight days of terror, they drifted in the ice-cold water, living on raw fish and on icicles plucked from the ruined rigging.

Suddenly birds wheeled on the horizon-first just a few like children's kites entangled in the sky, and then a gathering din, swooping and feeding. Below the swarm of birds was a tiny speck of bleak land, Torishima, or Bird Island, its steep volcanic cliffs jutting above the waves. The battered fishing boat capsized in the crashing surf and was smashed to pieces on the rocks. The five men dragged themselves to shore and collapsed-Jusuke's leg was badly mauled in the landing. Barely two miles in circumference and all but barren of vegetation or animal life, as the men discovered, Torishima was little more of a refuge than the drifting fishing boat. Birds, nothing but birds kept the men company. Six months of a hand-to-mouth existence out of Robinson Crusoe ensued: eating great-winged albatross that came so close that Manjiro, the most agile of the men, could kill them with a stone; scavenging for birds' eggs in the lava crevices; drinking brackish water scooped from rocks with a scallop shell. Then, as spring edged into burning summer, the birds too began to depart.

One clear morning three wavering sticks rose above the horizon. On the lookout, Manjiro tied a ragged kimono to a fragment of driftwood and waved it wildly from the shore. The apparition of a ship-huge and ungainly and indescribably odd, as it seemed to the Japanese fishermen-came steadily closer, like something dreamed in their abject desperation. Then bizarre sailors, some with light skin and some very dark, rowed in a small boat toward the island. In sign language, friendly invitations were issued, and the starved castaways were conveyed to the mother ship.

Captain William H. Whitfield, a stern New Englander with a clipped beard and piercing eyes, had brought the John Howland from her home port of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, in 1839, in search of whales in the waters east of Japan. Whaling captains had first discovered the fabled "Japan whaling grounds" twenty years earlier, as the overfished North Atlantic yielded fewer and fewer whales. Whitfield's crew had approached Torishima in hopes of finding giant sea turtles to relieve the monotony of their potatoes-and-hardtack diet. Instead they found five gaunt islanders-the Americans had no idea from whence they came and could make no sense of their language. They fed and clothed the shivering castaways, who looked at their rescuers with puzzled eyes.

Captain Whitfield then steered the John Howland on an eastward course toward the Sandwich Islands, hunting whales as he found them. Manjiro, quick-eyed and curious, was a favorite with the crew; they shortened his name to Mung, and added John in honor of their ship. Manjiro was astonished at the efficient violence practiced by these strangers. Four light whaling boats manned by six men each were lowered from the ship. With a sail or muffled oars, they approached the unwitting sperm whale and threw barbed harpoons into the domed head, holding on for dear life-the so-called Nantucket sleigh ride-as the whale tried desperately to free himself from the weapons lodged in his flesh. A boat could be dragged for miles, and at any moment the whale could dive downward or attack the boat, hurling the men into the sea. If all went well, the captured whale was butchered in the sea, and the flesh and blubber hacked into pieces and boiled down in vats on deck. These whalers, unlike the Japanese, did not eat the whale meat. The oil was what they were after, to light the houses of New England.

On November 20, 1841, the John Howland, with fourteen hundred barrels of sperm whale oil in its hold, dropped anchor in the port of Honolulu, on the southern coast of Oahu. The Sandwich Islands (later renamed Hawaii) were nominally an independent monarchy, with a king closely in league with American missionaries. With its dusty checkerboard streets lined with adobe walls, and a sprinkling of New England cottages incongruously mixed in among dingy native huts, Honolulu was part missionary town and part pleasure ground for sailors. Grogshops, brothels, and gambling dens had followed the onward march of civilization. With its strategic position along trade and whaling routes, Honolulu was the mid-ocean switching point for communications and travel in the Pacific, an obligatory stopping point for whalers, merchant ships, and naval vessels. Mail exchanged hands; newspapers were swapped; crew members could be hired and the sick or mutinous discharged.

Perched on the roof of his coral-pink church, Dr. Gerrit Parmele Judd was surprised to see his old friend Captain Whitfield, somber-clothed as always, leading five exotic strangers dressed in sailors' white duck along the main road. Dr. Judd, a Presbyterian missionary trained in medicine, was attaching the final shingles to his enormous new church, the Kaiwaiaho or "stone church." Hacked block by block by Hawaiian converts from coral reefs offshore, and built to house two thousand worshipers, the structure was the visual embodiment of Dr. Judd's far-reaching power and influence. From humble origins on the New England frontier, Dr. Judd had risen to high places. A tough-minded man with a jaw firmly clenched, he had won the confidence of King Kamehameha III and persuaded hundreds of native islanders, including the hard-drinking king, to sign a temperance pledge. Dr. Judd had also prevented Catholic priests from entering on British ships, keeping the islands pure of religious and national contamination.

Dr. Judd had seen many exotic islanders pass through the Sandwich Islands; he was particularly eager to identify the origins of Captain Whitfield's sea drifters. He spread a map of the Pacific on the ground before the fishermen, but they had never seen a map and had no idea what it signified. Then, from his house near the church, Dr. Judd brought some Japanese coins and pipes left by an earlier group of shipwrecked sailors. Manjiro and his friends smiled in happy recognition. Dr. Judd bowed low with his palms together. The men cried "Dai Nippon," and all five prostrated themselves on the ground. Satisfied that he had cracked the code, Dr. Judd quickly offered to hire Fudenjo, along with his brothers, Goemon and Jusuke, as house servants in his own household, with menial tasks such as drawing water and chopping firewood. Toraemon, more independent, found work as a carpenter and boat builder.

These arrangements left in doubt the fate of "John Mung." Captain Whitfield had been struck aboard ship by Manjiro's quick intellect and cheerful outlook. Manjiro picked up English words much faster than the other castaways. Nothing was lost on him, and for everything he sought an explanation and a name. Manjiro was particularly intrigued by the secrets of navigation and-in his broken English-asked question after question about how the ship could find its way with no visible landmarks by which to chart its course. The captain had a plan. A childless widower, he wished to take Manjiro back to Massachusetts with him, give him an education, and eventually adopt him as his son. Manjiro eagerly accepted the offer, and Captain Fudenjo gave his assent. As the John Howland made the long journey around Cape Horn in April 1843, and up the coasts of South and North America, Captain Whitfield had ample time to prepare Manjiro for what he might expect in the whaling town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts.

Spires jutting into the sky like the straight masts of ships and a bridge that broke in two so that tall ships could pass through: these were the sights that Manjiro, now sixteen years old, saw as the John Howland approached Fairhaven on May 7, 1843. The town, at the top of the jagged notch below Cape Cod known as Buzzards Bay, is true to its name: a protected harbor of deep and quiet water. A drawbridge spans the Acushnet River where it enters the harbor, connecting Fairhaven to the neighboring town of New Bedford. As Captain Whitfield explained the mechanism of the drawbridge, Manjiro, mesmerized by its operation, sketched it carefully. Then Whitfield pointed to a stone breakwater on the Fairhaven side and looming above it the proud battlements of Fort Phoenix, where the first naval engagement of the American Revolution took place.

Fairhaven, once called Poverty Point, has benefited from cycles of wealth and penury. The wealth accounts for the handsome Greek Revival houses of stone and clapboard that still line the narrow streets. The poverty accounts for the time-capsule preservation of so much of the town-money tends to mar. What wealth came to Fairhaven came from whales. Quaker shipowners in Fairhaven and New Bedford sent agents into the New England countryside to round up younger sons in search of more adventure than family farms could provide. Seasoned seamen were not fooled by the pitch; they signed instead with merchant ships bound for China or India. Only the gullible and the desperate fell for the whaler's promise of a minuscule share of the profits-minus whatever the owner claimed to have spent on the upkeep of the crew. Whaling ships were notorious for cruelty and hardship; they almost never returned with their crews intact. Even the John Howland, with an unusually civil captain, had lost eleven men, eight of whom deserted, during its three-and-a-half-year trip.

Captain Whitfield had found a son; he now went in search of a wife. He placed Manjiro temporarily in the household of a sailor friend and asked a teacher in the local school, Jane Allen, to tutor the boy after hours. After a week of tutoring sessions, Allen was so impressed with Manjiro's progress and aptitude that she enrolled him in the one-room stone school of Fairhaven. When Captain Whitfield returned with his bride, Albertina Keith, the Whitfields bought a farm on Sconticut Neck, and Manjiro joined them there as a member of the family, helping with daily chores and learning to ride a horse. Less enjoyable were the months he spent apprenticed to an impoverished cooper in New Bedford, learning the trade of barrel making. Neither the life of the farmer nor that of the tradesman appealed to Manjiro. The sea was his vocation, and somewhere in the back of his mind he retained the hope of returning to Japan to see his mother.

Those skills he had begun to learn onboard the John Howland-celestial navigation and the English language-Manjiro was able to perfect in Fairhaven, on the banks of the Acushnet River. The Christian Bible, an exotic tale of wizards and fishermen, meant little to Manjiro; his humiliation in the Fairhaven Congregational Church killed whatever enthusiasm he might have felt for the alien religion. Far more compelling was The New American Practical Navigator, by the Salem mathematician Nathaniel Bowditch, the guide to celestial navigation often called the sailor's bible. For this castaway who knew the perils of the open sea, Bowditch seemed the true savior. If Bowditch was a navigational tool on the perilous sea, Webster's Dictionary was for orientation in the world of men. These lessons-in language and navigation-proved to be the keys that opened the world for Manjiro.

From the Hardcover edition.

THE FLOATING WORLD

If that double-bolted land, Japan, is ever

to become hospitable, it is the whale-ship alone

to whom the credit will be due;

for already she is on the threshold.

-herman melville, moby-dick (1851)

Imagine the following scenario. Two fatherless boys on opposite sides of the earth take to the sea within days of each other, in search of adventure and a livelihood. Their paths cross on an archipelago in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, where they encounter some of the same helpers, and hinderers. One arrives after years of wandering at the other's port of departure. The other falls just short but writes an extraordinary book that completes the journey. One deserts a whaling ship while the other is rescued by one. One discovers the joys of savage life while the other discovers the ambiguous joys of civilization. Each dreams of "opening" the other's country, and each is changed utterly in the process; their reward is gloom and isolation. Now, let us give these lost boys and Pacific drifters names and dates.

I. The May Basket

During the waning hours of a warm spring evening in 1843, in the coastal

village of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, sixteen-year-old John Mung hung a May basket on the knocker of his classmate Catherine Terry's door. A note was hidden among the buttercups:

Tis in the chilly night

A basket you've got hung.

Get up, strike a light!

And see me run

But no take chase me.

Mung, according to age-old New England custom, ran off into the enveloping night-anonymous except for that telltale fifth line. Catherine Terry had reason to believe that the basket was "hung" by none other than John Mung, whom on occasion she had smiled at demurely during recess.

One Sunday morning, during that same spring of 1843, John Mung sat in Captain Whitfield's pew in the Fairhaven Congregational Church. After the service one of the elders of the church approached Captain Whitfield and quietly suggested that Mung should sit in the section reserved for escaped slaves. Mung was distracting the other worshipers, the elder explained, and would be more at home among the Negroes in the balcony.

Two years earlier John Mung had no idea that the town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, existed. He had never heard of the United States or of the English language. Rituals such as May baskets and the Christian Mass would have seemed to him impossibly foreign, and remote. In fact, no one by the name of John Mung existed in 1841. Call him Manjiro instead.

On January 5, 1841, in the Year of the Ox, the boy Manjiro, fourteen years old, boarded a boat with four other fishermen on the coast of Shikoku, the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. Manjiro, who lived with his mother in the tiny village of Nakanohama, had wandered up the coast in search of work. Captain Fudenjo of the village of Usa, near Tosa, had found Manjiro asleep on the sand and asked him to join his crew: his two brothers, Jusuke and Goemon, and another fisherman called Toraemon. In the fixed feudal order of Old Japan, peasants like Manjiro had only one name, and one life to look forward to. Like his father, who died when Manjiro was nine, and his grandfather and great-grandfather back into the mists of time, Manjiro would be a fisherman. What knocked him loose from this order established across millennia was a storm-the "great wind" called the typhoon.

Fudenjo's twenty-four-foot boat with a square sail, like all boats made in Japan, was equipped to hug the shore-to go farther out was strictly against the national laws and punishable by death. The nets came up empty for two days. On the third the crew suddenly found themselves in a school of mackerel. In their excitement they barely noticed that the wind-whipped waves had risen. They tugged hurriedly at the heavily laden nets, but by the time they had retrieved them the storm was in full force. Their efforts to gain control of the boat led to disaster; the sails were torn and the rudder split in two. Tempest-tossed, they watched helplessly as they drifted farther and farther out to sea. The next morning the color of the sea, dark indigo, confirmed their worst fears. They were caught in the Kuroshio, or Black Current, a Pacific counterpart of the Gulf Stream. The best they could hope for was an island in their path. For these five superstitious and illiterate men, the sea was boundless-until somewhere, without warning, one dropped off the edge. Through eight days of terror, they drifted in the ice-cold water, living on raw fish and on icicles plucked from the ruined rigging.

Suddenly birds wheeled on the horizon-first just a few like children's kites entangled in the sky, and then a gathering din, swooping and feeding. Below the swarm of birds was a tiny speck of bleak land, Torishima, or Bird Island, its steep volcanic cliffs jutting above the waves. The battered fishing boat capsized in the crashing surf and was smashed to pieces on the rocks. The five men dragged themselves to shore and collapsed-Jusuke's leg was badly mauled in the landing. Barely two miles in circumference and all but barren of vegetation or animal life, as the men discovered, Torishima was little more of a refuge than the drifting fishing boat. Birds, nothing but birds kept the men company. Six months of a hand-to-mouth existence out of Robinson Crusoe ensued: eating great-winged albatross that came so close that Manjiro, the most agile of the men, could kill them with a stone; scavenging for birds' eggs in the lava crevices; drinking brackish water scooped from rocks with a scallop shell. Then, as spring edged into burning summer, the birds too began to depart.

One clear morning three wavering sticks rose above the horizon. On the lookout, Manjiro tied a ragged kimono to a fragment of driftwood and waved it wildly from the shore. The apparition of a ship-huge and ungainly and indescribably odd, as it seemed to the Japanese fishermen-came steadily closer, like something dreamed in their abject desperation. Then bizarre sailors, some with light skin and some very dark, rowed in a small boat toward the island. In sign language, friendly invitations were issued, and the starved castaways were conveyed to the mother ship.

Captain William H. Whitfield, a stern New Englander with a clipped beard and piercing eyes, had brought the John Howland from her home port of Fairhaven, Massachusetts, in 1839, in search of whales in the waters east of Japan. Whaling captains had first discovered the fabled "Japan whaling grounds" twenty years earlier, as the overfished North Atlantic yielded fewer and fewer whales. Whitfield's crew had approached Torishima in hopes of finding giant sea turtles to relieve the monotony of their potatoes-and-hardtack diet. Instead they found five gaunt islanders-the Americans had no idea from whence they came and could make no sense of their language. They fed and clothed the shivering castaways, who looked at their rescuers with puzzled eyes.

Captain Whitfield then steered the John Howland on an eastward course toward the Sandwich Islands, hunting whales as he found them. Manjiro, quick-eyed and curious, was a favorite with the crew; they shortened his name to Mung, and added John in honor of their ship. Manjiro was astonished at the efficient violence practiced by these strangers. Four light whaling boats manned by six men each were lowered from the ship. With a sail or muffled oars, they approached the unwitting sperm whale and threw barbed harpoons into the domed head, holding on for dear life-the so-called Nantucket sleigh ride-as the whale tried desperately to free himself from the weapons lodged in his flesh. A boat could be dragged for miles, and at any moment the whale could dive downward or attack the boat, hurling the men into the sea. If all went well, the captured whale was butchered in the sea, and the flesh and blubber hacked into pieces and boiled down in vats on deck. These whalers, unlike the Japanese, did not eat the whale meat. The oil was what they were after, to light the houses of New England.

On November 20, 1841, the John Howland, with fourteen hundred barrels of sperm whale oil in its hold, dropped anchor in the port of Honolulu, on the southern coast of Oahu. The Sandwich Islands (later renamed Hawaii) were nominally an independent monarchy, with a king closely in league with American missionaries. With its dusty checkerboard streets lined with adobe walls, and a sprinkling of New England cottages incongruously mixed in among dingy native huts, Honolulu was part missionary town and part pleasure ground for sailors. Grogshops, brothels, and gambling dens had followed the onward march of civilization. With its strategic position along trade and whaling routes, Honolulu was the mid-ocean switching point for communications and travel in the Pacific, an obligatory stopping point for whalers, merchant ships, and naval vessels. Mail exchanged hands; newspapers were swapped; crew members could be hired and the sick or mutinous discharged.

Perched on the roof of his coral-pink church, Dr. Gerrit Parmele Judd was surprised to see his old friend Captain Whitfield, somber-clothed as always, leading five exotic strangers dressed in sailors' white duck along the main road. Dr. Judd, a Presbyterian missionary trained in medicine, was attaching the final shingles to his enormous new church, the Kaiwaiaho or "stone church." Hacked block by block by Hawaiian converts from coral reefs offshore, and built to house two thousand worshipers, the structure was the visual embodiment of Dr. Judd's far-reaching power and influence. From humble origins on the New England frontier, Dr. Judd had risen to high places. A tough-minded man with a jaw firmly clenched, he had won the confidence of King Kamehameha III and persuaded hundreds of native islanders, including the hard-drinking king, to sign a temperance pledge. Dr. Judd had also prevented Catholic priests from entering on British ships, keeping the islands pure of religious and national contamination.

Dr. Judd had seen many exotic islanders pass through the Sandwich Islands; he was particularly eager to identify the origins of Captain Whitfield's sea drifters. He spread a map of the Pacific on the ground before the fishermen, but they had never seen a map and had no idea what it signified. Then, from his house near the church, Dr. Judd brought some Japanese coins and pipes left by an earlier group of shipwrecked sailors. Manjiro and his friends smiled in happy recognition. Dr. Judd bowed low with his palms together. The men cried "Dai Nippon," and all five prostrated themselves on the ground. Satisfied that he had cracked the code, Dr. Judd quickly offered to hire Fudenjo, along with his brothers, Goemon and Jusuke, as house servants in his own household, with menial tasks such as drawing water and chopping firewood. Toraemon, more independent, found work as a carpenter and boat builder.

These arrangements left in doubt the fate of "John Mung." Captain Whitfield had been struck aboard ship by Manjiro's quick intellect and cheerful outlook. Manjiro picked up English words much faster than the other castaways. Nothing was lost on him, and for everything he sought an explanation and a name. Manjiro was particularly intrigued by the secrets of navigation and-in his broken English-asked question after question about how the ship could find its way with no visible landmarks by which to chart its course. The captain had a plan. A childless widower, he wished to take Manjiro back to Massachusetts with him, give him an education, and eventually adopt him as his son. Manjiro eagerly accepted the offer, and Captain Fudenjo gave his assent. As the John Howland made the long journey around Cape Horn in April 1843, and up the coasts of South and North America, Captain Whitfield had ample time to prepare Manjiro for what he might expect in the whaling town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts.

Spires jutting into the sky like the straight masts of ships and a bridge that broke in two so that tall ships could pass through: these were the sights that Manjiro, now sixteen years old, saw as the John Howland approached Fairhaven on May 7, 1843. The town, at the top of the jagged notch below Cape Cod known as Buzzards Bay, is true to its name: a protected harbor of deep and quiet water. A drawbridge spans the Acushnet River where it enters the harbor, connecting Fairhaven to the neighboring town of New Bedford. As Captain Whitfield explained the mechanism of the drawbridge, Manjiro, mesmerized by its operation, sketched it carefully. Then Whitfield pointed to a stone breakwater on the Fairhaven side and looming above it the proud battlements of Fort Phoenix, where the first naval engagement of the American Revolution took place.

Fairhaven, once called Poverty Point, has benefited from cycles of wealth and penury. The wealth accounts for the handsome Greek Revival houses of stone and clapboard that still line the narrow streets. The poverty accounts for the time-capsule preservation of so much of the town-money tends to mar. What wealth came to Fairhaven came from whales. Quaker shipowners in Fairhaven and New Bedford sent agents into the New England countryside to round up younger sons in search of more adventure than family farms could provide. Seasoned seamen were not fooled by the pitch; they signed instead with merchant ships bound for China or India. Only the gullible and the desperate fell for the whaler's promise of a minuscule share of the profits-minus whatever the owner claimed to have spent on the upkeep of the crew. Whaling ships were notorious for cruelty and hardship; they almost never returned with their crews intact. Even the John Howland, with an unusually civil captain, had lost eleven men, eight of whom deserted, during its three-and-a-half-year trip.

Captain Whitfield had found a son; he now went in search of a wife. He placed Manjiro temporarily in the household of a sailor friend and asked a teacher in the local school, Jane Allen, to tutor the boy after hours. After a week of tutoring sessions, Allen was so impressed with Manjiro's progress and aptitude that she enrolled him in the one-room stone school of Fairhaven. When Captain Whitfield returned with his bride, Albertina Keith, the Whitfields bought a farm on Sconticut Neck, and Manjiro joined them there as a member of the family, helping with daily chores and learning to ride a horse. Less enjoyable were the months he spent apprenticed to an impoverished cooper in New Bedford, learning the trade of barrel making. Neither the life of the farmer nor that of the tradesman appealed to Manjiro. The sea was his vocation, and somewhere in the back of his mind he retained the hope of returning to Japan to see his mother.

Those skills he had begun to learn onboard the John Howland-celestial navigation and the English language-Manjiro was able to perfect in Fairhaven, on the banks of the Acushnet River. The Christian Bible, an exotic tale of wizards and fishermen, meant little to Manjiro; his humiliation in the Fairhaven Congregational Church killed whatever enthusiasm he might have felt for the alien religion. Far more compelling was The New American Practical Navigator, by the Salem mathematician Nathaniel Bowditch, the guide to celestial navigation often called the sailor's bible. For this castaway who knew the perils of the open sea, Bowditch seemed the true savior. If Bowditch was a navigational tool on the perilous sea, Webster's Dictionary was for orientation in the world of men. These lessons-in language and navigation-proved to be the keys that opened the world for Manjiro.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Advance praise for The Great Wave

“The close-up brilliance of Christopher Benfey’s depiction of the early stages of the encounter between sophisticated representatives of the American Gilded Age and those of nineteenth-century Japan required an assured grasp of both cultures, their assumptions and envies, their gifts and weaknesses, their humor and lack of it. He has portrayed this mutual loss of virginity with grace, wit, and a range of reference that re-echoes the original astonishments and is a pleasure to read.”

—W. S. Merwin

Praise for Christopher Benfey

Degas in New Orleans

“Yes, Degas in New Orleans involves a haunted house, ghosts, and titillating couplings, but all elements are solidly anchored in historical events and retold by Christopher Benfey in a deft synthesis of art criticism and historical speculation....An elegant introduction to a city that remains a secretive, seductive metropolis.”

—Grace Lichtenstein, The Washington Post Book World

The Double Life of Stephen Crane

“In this astute and subtle new reading of Stephen Crane, Christopher Benfey discovers the mysterious process of a life taking shape from its art. Mr. Benfey writes beautifully and is as sharp on the social and psychological dimensions of Crane’s experience as he is on language and literary craft.”

—Jean Strouse, author of Alice James

From the Hardcover edition.

“The close-up brilliance of Christopher Benfey’s depiction of the early stages of the encounter between sophisticated representatives of the American Gilded Age and those of nineteenth-century Japan required an assured grasp of both cultures, their assumptions and envies, their gifts and weaknesses, their humor and lack of it. He has portrayed this mutual loss of virginity with grace, wit, and a range of reference that re-echoes the original astonishments and is a pleasure to read.”

—W. S. Merwin

Praise for Christopher Benfey

Degas in New Orleans

“Yes, Degas in New Orleans involves a haunted house, ghosts, and titillating couplings, but all elements are solidly anchored in historical events and retold by Christopher Benfey in a deft synthesis of art criticism and historical speculation....An elegant introduction to a city that remains a secretive, seductive metropolis.”

—Grace Lichtenstein, The Washington Post Book World

The Double Life of Stephen Crane

“In this astute and subtle new reading of Stephen Crane, Christopher Benfey discovers the mysterious process of a life taking shape from its art. Mr. Benfey writes beautifully and is as sharp on the social and psychological dimensions of Crane’s experience as he is on language and literary craft.”

—Jean Strouse, author of Alice James

From the Hardcover edition.