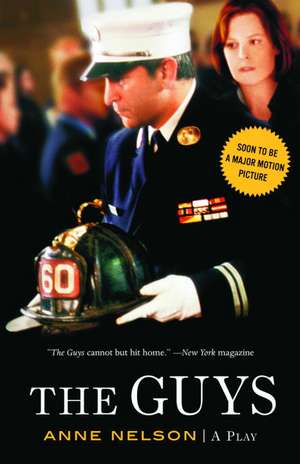

The Guys: A Play

Autor Anne Nelsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Audies (2003)

Paralyzed by grief and unable to put his thoughts into words, Nick, a fire captain, seeks out the help of a writer to compose eulogies for the colleagues and friends he lost in the catastrophic events of September 11, 2001. As Joan, an editor by trade, draws Nick out about “the guys,” powerful profiles emerge, revealing vivid personalities and the substance and meaning that lie beneath the surface of seemingly unremarkable people. As the individual talents and enthusiasms of the people within the small firehouse community are realized, we come to understand the uniqueness and value of what each person has to contribute. And Nick and Joan, two people who under normal circumstances never would have met, jump the well-defined tracks of their own lives, and so learn about themselves, about life, and about the healing power of human connection, through talking about the guys.

Preț: 76.14 lei

Preț vechi: 99.90 lei

-24% Nou

Puncte Express: 114

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.57€ • 15.18$ • 12.12£

14.57€ • 15.18$ • 12.12£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21-28 ianuarie 25

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812967296

ISBN-10: 0812967291

Pagini: 128

Ilustrații: 9 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 130 x 205 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 0812967291

Pagini: 128

Ilustrații: 9 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 130 x 205 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.14 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Extras

Preface

The Guys is based on a true experience.

I teach at the graduate school for journalism at Columbia University in New York, and I oversee some thirty international students. On the morning of September 11, 2001, we had sent them out, along with their American classmates, to cover the mayoral primary. It would be days before we knew that all of them had survived.

I had learned about the attack on the World Trade Center in a call from my father in

Oklahoma. I watched the images on television until the second tower went down. Then, numb, I turned off the television, voted, and went to my office. I remember taking out my calendar and looking at it, wondering which of the events I had planned, if any, now had any meaning. I walked over to the hospital on the next block to donate blood. The emergency personnel turned me away. They were kind, but they wanted to keep the hospital clear for the wounded. They looked over my shoulder as they talked to me, searching the traffic lanes down Amsterdam Avenue for ambulances bearing victims of the attack–those ambulances that would in fact never arrive uptown. There were far fewer wounded than anyone expected. Most of the casualties were dead.

Twelve days after the attack, my husband and I took our children to visit my sister and brother-in-law in Brooklyn. Families in New York wanted to huddle, to eat together, and to talk quietly. A friend of my sister’s called, looking for my brother-in-law, Burk Bilger, who is also a writer. The friend had met a fire captain and wanted to find someone who could help him. Burk was working on deadline, so I said I would help. The captain came over that afternoon. Once he got there, he told us his story: He had lost most of the men from his company who had responded to the alarm at the World Trade Center. The first service was only days away, and as the captain, he had to deliver the eulogy. But he couldn’t find a way to write anything. Burk put aside his project and joined us. He and I reassured the captain and started to work. Together, the three of us spent hours producing eulogies. Burk and I worked in shifts, one of us interviewing the fire captain while the other wrote. It was clear to us that the captain, like many New Yorkers that month, was quite literally in a state of shock. Suddenly, a significant number of the people he was closest to simply weren’t there. Yet in only a few days he was supposed to get up and speak before hundreds of mourners, to put something into words that would reflect their loss, as well as their esteem and affection for the fallen man.

Through the strange mathematics of chance, neither my brother-in-law nor I had lost anyone close to us in the catastrophe. But like most New Yorkers, we were stunned, grieved, uncomprehending. That afternoon turned into evening, and at last we finished the final eulogy for the services that had been scheduled. The captain thanked us, several times, and then said, “You should come to the firehouse and see what I’m talking about.”

I did, a few days later. Like most civilians, I had never ventured beyond the firehouse doors. I saw the environment described in the play–the kitchen, the tool bench, the black boots set out on the floor ready for the firefighters to jump into at a call. I saw a long row of names written in chalk on a blackboard, which listed men as “missing” even though, since it was two weeks past 9/11, those men were surely lost.

The captain and I kept in touch. More services were scheduled. He came uptown, and together we wrote more eulogies. He delivered them at the services, and I would call to find out how they went. I could tell that every step was an ordeal for him, because he, utterly unreasonably, felt responsible. Like fire captains across the city, he wanted to take care of the families of the survivors, to compensate for their loss in a way no one possibly could. He would do everything for them he could remotely think of, and then berate himself for not doing enough. At the same time, he had to look after his men at the firehouse, whose world and whose way of life had been instantly and permanently changed.

The captain impressed me deeply. I thought that I had never met anyone so generous. I realized that generosity was the essence of the job–a firefighter’s work was about saving lives, and the more often and effectively he did it, the happier he was. I also learned that like many of his counterparts, the captain had a boundless curiosity toward the world around him, including a fresh and eager appetite for the arts. That first meeting in September opened a door to the world of the firefighters, and as I continued to learn about them, my admiration grew. Over the coming weeks I read reams of press coverage on the aftermath of 9/11, but I felt as though my experience had given me a glimpse into another dimension. Three hundred and forty-three firemen lost is a number. I had had the privilege of being introduced to men–their qualities, their families, their daily life–in a way that made them real to me, and allowed me to mourn them and the others who had died.

In early October, some Argentine colleagues asked me to appear on a panel in Buenos Aires. It was my first time out of the country since 9/11, and it made for a rough trip. The journey was a bizarre inversion of the time I had spent reporting from Latin America in the early 1980s. Now the airport that was filled with soldiers and submachine guns was in the United States–JFK. When I got to Argentina, I stopped at a corner bar for an empanada, and the waiter blithely informed me that “an anthrax bomb was just dropped on New York.” He had gotten the story wrong, but it was a horrific half-hour before I found that out, a half-hour in which my only thought was that I should have been in New York with my children.

Over the next few days, I learned that the Argentines had their own perspective on the attack–or, rather, many different perspectives, ranging from the humane empathy of the many to the callous satisfaction of the few: There were some people, in some parts of the world, who saw the attack on the innocents of the World Trade Center as retribution for actions of the U.S. government. In the following days and weeks I learned, with the help of my international students, that each culture brought its own idiosyncratic interpretation to the event. Those interpretations made a jarring addition to my twenty-five years of experience in the fields of journalism, human rights, and international affairs. In my mind, the trip to Argentina came to illustrate the negative perception of Americans in other parts of the world, something Americans have difficulty understanding.

On October 18, shortly after I returned to New York, I attended a benefit dinner for my husband’s organization, the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights. Sitting at my right hand was a pleasant-looking man named Jim Simpson, who was married to a Lawyers Committee board member, Sigourney Weaver. Jim and I were on duty as spouses, and over dinner, the conversation quickly turned to September 11. He told me that he had founded a small theater and repertory company in TriBeCa, just seven blocks from the World Trade Center. The Flea Theater had been flourishing but was now in danger of going under. Because of the attack, the area had been closed off for weeks, and once it became accessible, audiences avoided it because of the smoke and debris, as well as the general pall of disaster. Businesses all over the neighborhood were dying. The Flea Theater continued to operate, but the company was playing to empty houses. One of his young actors, Jim said, wanted to do a play that spoke to the situation directly. But what could that play be?

“Antigone?” I suggested. Maybe not. What about Brecht? We talked through the classical repertory, but Jim concluded, “It has to be something new. But it doesn’t exist.”

I commiserated. At the same time, I felt paralyzed as a writer. New York was full of journalists, and they were producing miles of newsprint. I was teaching and did not have a regular outlet. Yet writing was what I did–writing was how I had always made sense of the world. I felt a building pressure to write something to help me make sense of what had happened, and was happening now. Jim and I agreed that it would be good to have a further conversation, but I didn’t really expect anything to come of it. But Jim followed up the next day with an e-mail. Somewhere along the way, I brought up the eulogies and told him how writing them had affected me. Jim encouraged me to write a play based on the experience. He suggested a “two-hander”–a play with two characters–alternating monologues and dialogue, a play that would compress the experiences and emotions of those first raw weeks into a single ninety-minute encounter.

I hadn’t written a play before, but I was motivated to capture what I had observed and experienced through my conversations with the captain. I also wanted to try to help the theater. I loved the sound of what Jim had described–a small, noncommercial space, unpretentious but beautifully designed, with a young repertory company whose members were there for the love of the craft. It was the sort of enterprise that had drawn me to New York in the first place, and part of me felt–not entirely coherently–that if we could somehow keep it alive, it would deprive the attackers of another victory.

That night I visited the firehouse again. “Look,” I told the captain. “I’ve been asked about writing a play. I’d like to try it, but I won’t if you have a problem with it. And I won’t include anything that you think would hurt anyone.”

He considered it, and looked straight at me. “Do it,” he said. As it happens, the captain is an off-off-Broadway theater buff. In keeping with his nature, he was worried about small theaters suffering from the attack and about the young actors who would be thrown out of work. And I think that he was clear from the very beginning that this might serve as a memorial of words, both to those who had died and to those who were trying to find a way to go on. I told the captain I would change names and details in the interests of people’s privacy. He wanted to remain anonymous, and I said I’d do everything I could to achieve that. But I also said I wanted to share the essence of what I’d learned.

“I want people to know about these guys,” I told him.

“Yeah,” he said. “So do I.”

I went home and started to write. I would start my days at the office, go home and, with my husband, feed our children and put them to bed, and then end up at the computer, writing into the small hours of the morning. I only wrote at night, liberated by the license of sleep deprivation. I have never written anything in such an uninterrupted fashion. No outline, few preconceptions, no notion of what would be the beginning, middle, or end. I just typed forward. I think it helped that I had no certainty it would ever be produced.

I am a compulsive note-taker at all times, and I had been one through the fall of 2001 as well. I had pages of legal pads filled with quotes, facts, and expressions that puzzled or pleased me, all in what I had come to think of as the metallic music of firehouse speech. Above all, I wanted to capture that voice, because I thought it was beautiful and because it expressed humor and compassion in such a natural and unexpected way. I tried to protect individuals from unwanted publicity by changing everything I could: names, places, physical characteristics. I fictionalized details in some places and created composite characters in others. But sometimes the material defeated my intentions.

When I came to write about the tool bench in the firehouse, nothing would do but to write about the tool bench. And so the tool bench remained.

I also thought about changing a reference to my own home state, Oklahoma. But I wanted to preserve the unspoken resonance of the Oklahoma City bombing, which had shaken us all so deeply and yet was now dwarfed by this even more catastrophic event.

A little over a week later, I e-mailed a draft of the play to Jim. I called him the next day, saying that I had to fly to Barcelona to give a lecture. I would welcome his comments so that I could work on a rewrite on the plane. “Take the weekend off,” he said.

When I got back, Jim said he wanted to produce it. I was taken aback. I called the captain, who had not expected anything to be written so quickly. He came up to my apartment, and my husband and I read the play aloud to him. “Do it,” he said. “It’s what happened.” He asked me to make two changes–nothing I would ever have expected, but points that were sensitive to firehouse culture. I made the changes instantly.

Jim had asked me if I had any problem with the idea of his wife, Sigourney Weaver, playing the role of the editor. Dream on, I thought. “No problem,” I answered. In short order, I was told that she had contacted her friend Bill Murray about playing the fire captain. The four of us met in Jim and Sigourney’s living room several times a week, with Bill and Sigourney reading over the piece, making minor adjustments, and letting it sink in. The three of them brought acute intelligence and an instant, fierce commitment to the project. I cannot remember any collaboration, at any point in my career, being as satisfying as this one. We sat in that light-flooded room over a dozen November mornings and I, as a first-time playwright, listened as they breathed life into the words of The Guys.

We all wanted the play to open soon. Jim decided to stage the piece as a workshop, with scripts on music stands, in a form that had been developed by A. R. Gurney in Love Letters. Jim is a brilliantly minimalist director, and settled on a production with few props, a set made up of little more than a pair of chairs and a table. The dominant colors were magenta and cobalt. The effect was of something glowing. I told friends not to expect any recent trends from the theater–no sex, no violence, no obscenity. The “special effects” consisted of turning the lights on and the captain putting on a hat.

Only days before The Guys was scheduled to open, I realized that we didn’t have the rights to the music for the tango and there was no time to obtain them. A tune came into my head one day on the subway, no doubt the fruit of my affection for Argentina and the music of Carlos Gardel. I jotted it down in my notebook and invited my son’s violin teacher, Nathan Lanier, to help with an arrangement. He brought some friends to the theater the next afternoon and they recorded it as a string trio. Somehow it was all in the spirit of the work.

The Guys premiered as a workshop production at the Flea Theater in New York with Sigourney Weaver and Bill Murray. It opened on Tuesday, December 4, 2001, twelve weeks to the day after the World Trade Center attack.

The Guys is based on a true experience.

I teach at the graduate school for journalism at Columbia University in New York, and I oversee some thirty international students. On the morning of September 11, 2001, we had sent them out, along with their American classmates, to cover the mayoral primary. It would be days before we knew that all of them had survived.

I had learned about the attack on the World Trade Center in a call from my father in

Oklahoma. I watched the images on television until the second tower went down. Then, numb, I turned off the television, voted, and went to my office. I remember taking out my calendar and looking at it, wondering which of the events I had planned, if any, now had any meaning. I walked over to the hospital on the next block to donate blood. The emergency personnel turned me away. They were kind, but they wanted to keep the hospital clear for the wounded. They looked over my shoulder as they talked to me, searching the traffic lanes down Amsterdam Avenue for ambulances bearing victims of the attack–those ambulances that would in fact never arrive uptown. There were far fewer wounded than anyone expected. Most of the casualties were dead.

Twelve days after the attack, my husband and I took our children to visit my sister and brother-in-law in Brooklyn. Families in New York wanted to huddle, to eat together, and to talk quietly. A friend of my sister’s called, looking for my brother-in-law, Burk Bilger, who is also a writer. The friend had met a fire captain and wanted to find someone who could help him. Burk was working on deadline, so I said I would help. The captain came over that afternoon. Once he got there, he told us his story: He had lost most of the men from his company who had responded to the alarm at the World Trade Center. The first service was only days away, and as the captain, he had to deliver the eulogy. But he couldn’t find a way to write anything. Burk put aside his project and joined us. He and I reassured the captain and started to work. Together, the three of us spent hours producing eulogies. Burk and I worked in shifts, one of us interviewing the fire captain while the other wrote. It was clear to us that the captain, like many New Yorkers that month, was quite literally in a state of shock. Suddenly, a significant number of the people he was closest to simply weren’t there. Yet in only a few days he was supposed to get up and speak before hundreds of mourners, to put something into words that would reflect their loss, as well as their esteem and affection for the fallen man.

Through the strange mathematics of chance, neither my brother-in-law nor I had lost anyone close to us in the catastrophe. But like most New Yorkers, we were stunned, grieved, uncomprehending. That afternoon turned into evening, and at last we finished the final eulogy for the services that had been scheduled. The captain thanked us, several times, and then said, “You should come to the firehouse and see what I’m talking about.”

I did, a few days later. Like most civilians, I had never ventured beyond the firehouse doors. I saw the environment described in the play–the kitchen, the tool bench, the black boots set out on the floor ready for the firefighters to jump into at a call. I saw a long row of names written in chalk on a blackboard, which listed men as “missing” even though, since it was two weeks past 9/11, those men were surely lost.

The captain and I kept in touch. More services were scheduled. He came uptown, and together we wrote more eulogies. He delivered them at the services, and I would call to find out how they went. I could tell that every step was an ordeal for him, because he, utterly unreasonably, felt responsible. Like fire captains across the city, he wanted to take care of the families of the survivors, to compensate for their loss in a way no one possibly could. He would do everything for them he could remotely think of, and then berate himself for not doing enough. At the same time, he had to look after his men at the firehouse, whose world and whose way of life had been instantly and permanently changed.

The captain impressed me deeply. I thought that I had never met anyone so generous. I realized that generosity was the essence of the job–a firefighter’s work was about saving lives, and the more often and effectively he did it, the happier he was. I also learned that like many of his counterparts, the captain had a boundless curiosity toward the world around him, including a fresh and eager appetite for the arts. That first meeting in September opened a door to the world of the firefighters, and as I continued to learn about them, my admiration grew. Over the coming weeks I read reams of press coverage on the aftermath of 9/11, but I felt as though my experience had given me a glimpse into another dimension. Three hundred and forty-three firemen lost is a number. I had had the privilege of being introduced to men–their qualities, their families, their daily life–in a way that made them real to me, and allowed me to mourn them and the others who had died.

In early October, some Argentine colleagues asked me to appear on a panel in Buenos Aires. It was my first time out of the country since 9/11, and it made for a rough trip. The journey was a bizarre inversion of the time I had spent reporting from Latin America in the early 1980s. Now the airport that was filled with soldiers and submachine guns was in the United States–JFK. When I got to Argentina, I stopped at a corner bar for an empanada, and the waiter blithely informed me that “an anthrax bomb was just dropped on New York.” He had gotten the story wrong, but it was a horrific half-hour before I found that out, a half-hour in which my only thought was that I should have been in New York with my children.

Over the next few days, I learned that the Argentines had their own perspective on the attack–or, rather, many different perspectives, ranging from the humane empathy of the many to the callous satisfaction of the few: There were some people, in some parts of the world, who saw the attack on the innocents of the World Trade Center as retribution for actions of the U.S. government. In the following days and weeks I learned, with the help of my international students, that each culture brought its own idiosyncratic interpretation to the event. Those interpretations made a jarring addition to my twenty-five years of experience in the fields of journalism, human rights, and international affairs. In my mind, the trip to Argentina came to illustrate the negative perception of Americans in other parts of the world, something Americans have difficulty understanding.

On October 18, shortly after I returned to New York, I attended a benefit dinner for my husband’s organization, the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights. Sitting at my right hand was a pleasant-looking man named Jim Simpson, who was married to a Lawyers Committee board member, Sigourney Weaver. Jim and I were on duty as spouses, and over dinner, the conversation quickly turned to September 11. He told me that he had founded a small theater and repertory company in TriBeCa, just seven blocks from the World Trade Center. The Flea Theater had been flourishing but was now in danger of going under. Because of the attack, the area had been closed off for weeks, and once it became accessible, audiences avoided it because of the smoke and debris, as well as the general pall of disaster. Businesses all over the neighborhood were dying. The Flea Theater continued to operate, but the company was playing to empty houses. One of his young actors, Jim said, wanted to do a play that spoke to the situation directly. But what could that play be?

“Antigone?” I suggested. Maybe not. What about Brecht? We talked through the classical repertory, but Jim concluded, “It has to be something new. But it doesn’t exist.”

I commiserated. At the same time, I felt paralyzed as a writer. New York was full of journalists, and they were producing miles of newsprint. I was teaching and did not have a regular outlet. Yet writing was what I did–writing was how I had always made sense of the world. I felt a building pressure to write something to help me make sense of what had happened, and was happening now. Jim and I agreed that it would be good to have a further conversation, but I didn’t really expect anything to come of it. But Jim followed up the next day with an e-mail. Somewhere along the way, I brought up the eulogies and told him how writing them had affected me. Jim encouraged me to write a play based on the experience. He suggested a “two-hander”–a play with two characters–alternating monologues and dialogue, a play that would compress the experiences and emotions of those first raw weeks into a single ninety-minute encounter.

I hadn’t written a play before, but I was motivated to capture what I had observed and experienced through my conversations with the captain. I also wanted to try to help the theater. I loved the sound of what Jim had described–a small, noncommercial space, unpretentious but beautifully designed, with a young repertory company whose members were there for the love of the craft. It was the sort of enterprise that had drawn me to New York in the first place, and part of me felt–not entirely coherently–that if we could somehow keep it alive, it would deprive the attackers of another victory.

That night I visited the firehouse again. “Look,” I told the captain. “I’ve been asked about writing a play. I’d like to try it, but I won’t if you have a problem with it. And I won’t include anything that you think would hurt anyone.”

He considered it, and looked straight at me. “Do it,” he said. As it happens, the captain is an off-off-Broadway theater buff. In keeping with his nature, he was worried about small theaters suffering from the attack and about the young actors who would be thrown out of work. And I think that he was clear from the very beginning that this might serve as a memorial of words, both to those who had died and to those who were trying to find a way to go on. I told the captain I would change names and details in the interests of people’s privacy. He wanted to remain anonymous, and I said I’d do everything I could to achieve that. But I also said I wanted to share the essence of what I’d learned.

“I want people to know about these guys,” I told him.

“Yeah,” he said. “So do I.”

I went home and started to write. I would start my days at the office, go home and, with my husband, feed our children and put them to bed, and then end up at the computer, writing into the small hours of the morning. I only wrote at night, liberated by the license of sleep deprivation. I have never written anything in such an uninterrupted fashion. No outline, few preconceptions, no notion of what would be the beginning, middle, or end. I just typed forward. I think it helped that I had no certainty it would ever be produced.

I am a compulsive note-taker at all times, and I had been one through the fall of 2001 as well. I had pages of legal pads filled with quotes, facts, and expressions that puzzled or pleased me, all in what I had come to think of as the metallic music of firehouse speech. Above all, I wanted to capture that voice, because I thought it was beautiful and because it expressed humor and compassion in such a natural and unexpected way. I tried to protect individuals from unwanted publicity by changing everything I could: names, places, physical characteristics. I fictionalized details in some places and created composite characters in others. But sometimes the material defeated my intentions.

When I came to write about the tool bench in the firehouse, nothing would do but to write about the tool bench. And so the tool bench remained.

I also thought about changing a reference to my own home state, Oklahoma. But I wanted to preserve the unspoken resonance of the Oklahoma City bombing, which had shaken us all so deeply and yet was now dwarfed by this even more catastrophic event.

A little over a week later, I e-mailed a draft of the play to Jim. I called him the next day, saying that I had to fly to Barcelona to give a lecture. I would welcome his comments so that I could work on a rewrite on the plane. “Take the weekend off,” he said.

When I got back, Jim said he wanted to produce it. I was taken aback. I called the captain, who had not expected anything to be written so quickly. He came up to my apartment, and my husband and I read the play aloud to him. “Do it,” he said. “It’s what happened.” He asked me to make two changes–nothing I would ever have expected, but points that were sensitive to firehouse culture. I made the changes instantly.

Jim had asked me if I had any problem with the idea of his wife, Sigourney Weaver, playing the role of the editor. Dream on, I thought. “No problem,” I answered. In short order, I was told that she had contacted her friend Bill Murray about playing the fire captain. The four of us met in Jim and Sigourney’s living room several times a week, with Bill and Sigourney reading over the piece, making minor adjustments, and letting it sink in. The three of them brought acute intelligence and an instant, fierce commitment to the project. I cannot remember any collaboration, at any point in my career, being as satisfying as this one. We sat in that light-flooded room over a dozen November mornings and I, as a first-time playwright, listened as they breathed life into the words of The Guys.

We all wanted the play to open soon. Jim decided to stage the piece as a workshop, with scripts on music stands, in a form that had been developed by A. R. Gurney in Love Letters. Jim is a brilliantly minimalist director, and settled on a production with few props, a set made up of little more than a pair of chairs and a table. The dominant colors were magenta and cobalt. The effect was of something glowing. I told friends not to expect any recent trends from the theater–no sex, no violence, no obscenity. The “special effects” consisted of turning the lights on and the captain putting on a hat.

Only days before The Guys was scheduled to open, I realized that we didn’t have the rights to the music for the tango and there was no time to obtain them. A tune came into my head one day on the subway, no doubt the fruit of my affection for Argentina and the music of Carlos Gardel. I jotted it down in my notebook and invited my son’s violin teacher, Nathan Lanier, to help with an arrangement. He brought some friends to the theater the next afternoon and they recorded it as a string trio. Somehow it was all in the spirit of the work.

The Guys premiered as a workshop production at the Flea Theater in New York with Sigourney Weaver and Bill Murray. It opened on Tuesday, December 4, 2001, twelve weeks to the day after the World Trade Center attack.

Recenzii

“The Guys cannot but hit home.”

—New York magazine

“A stark and simple, potent and poignant play, brimming with edgy humanity.”

—New York Post

“The Guys is not an ordinary night in the theater....What comes through is that humanity can be exalted by expression as well as the other way around.”

—The New York Times

“New York’s most cathartic theater event.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“[The Guys] goes beyond theater. It’s not just entertainment. It [is] a real, moving document.” —Robert Altman

—New York magazine

“A stark and simple, potent and poignant play, brimming with edgy humanity.”

—New York Post

“The Guys is not an ordinary night in the theater....What comes through is that humanity can be exalted by expression as well as the other way around.”

—The New York Times

“New York’s most cathartic theater event.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“[The Guys] goes beyond theater. It’s not just entertainment. It [is] a real, moving document.” —Robert Altman

Descriere

The sold-out play, soon to be a movie starring Sigourney Weaver and Anthony LaPaglia--is about a woman who volunteers to help a fire captain write tributes to the men he lost in the World Trade Center disaster--ordinary human beings who became heroes.

Notă biografică

Premii

- Audies Winner, 2003