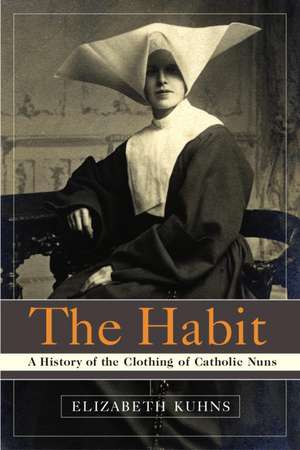

The Habit: A History of the Clothing of Catholic Nuns

Autor Elizabeth Kuhnsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2005

From the clothing seen in an eleventh-century monastery to the garb worn by nuns on picket lines during the 1960s, habits have always been designed to convey a specific image or ideal. The habits of the Benedictines and the Dominicans, for example, were specifically created to distinguish women who consecrated their lives to God; other habits reflected the sisters’ desire to blend in among the people they served. The brown Carmelite habit was rarely seen outside the monastery wall, while the Flying Nun turned the white winged cornette of the Daughters of Charity into a universally recognized icon. And when many religious abandoned habits in the 1960s and ’70s, it stirred a debate that continues today.

Drawing on archival research and personal interviews with nuns all over the United States, Elizabeth Kuhns examines some of the gender and identity issues behind the controversy and brings to light the paradoxes the habit represents. For some, it epitomizes oppression and obsolescence; for others, it embodies the ultimate beauty and dignity of the vocation.

Complete with extraordinary photographs, including images of the nineteenth century nuns’ silk bonnets to the simple gray dresses of the Sisters of Social Service, this evocative narrative explores the timeless symbolism of the habit and traces its evolution as a visual reflection of the changes in society.

Preț: 106.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.45€ • 21.35$ • 16.92£

20.45€ • 21.35$ • 16.92£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385505895

ISBN-10: 0385505892

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 142 x 212 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: IMAGE

ISBN-10: 0385505892

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 142 x 212 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: IMAGE

Notă biografică

Elizabeth Kuhns writes on Catholic traditions for a variety of publications. She is a regular contributor to Faith & Family: The Magazine of Catholic Living, and has previously worked for the Book-of-the-Month Club and the New Hampshire Humanities Council.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

Enigma

A Catholic sister wearing religious garb can board a city bus and not be surprised if the bus driver places his hand over the fare box, insisting she ride free of charge. Respect for the habit remains universal--nun imposters who panhandle in city subways bank on wearing it to collect as much as $600 per day. It also can be an easy target for lampooning--consider the popular "Fighting Nun" puppet or the "Nunzilla" windup toy.1

The nun's habit is one of the most widely known and recognizable religious symbols of our time, an icon deeply embedded in our cultural consciousness. Perhaps the habit has continued to fascinate us because of its unique blend of associations. As memoirist Mary Gordon recently wrote, "The image, the idea, of a nun brings together three powerful elements: God, women, and sex."

At the same time that the habit serves to shroud the body and to mask the individual, it also dramatically announces its wearer to the world. The habit has the glamour of fashion while being antifashion; it is the antithesis of extravagance and sexual allure, yet it impresses and arouses. The sighting of a nun in habit remains for most of us a notable event, because what the habit proclaims is something so counterculture and so radical, we cannot help but to react with awe and reverence or with suspicion and disdain. From this clothing, we immediately recognize a woman who has decided to commit her life fully to God, to renounce the possibility of bearing children, and to work within the boundaries of a community for some specific sacred purpose, frequently in neglected or controversial areas. She seems both less than female but greater than human--it was not unusual for schoolchildren of only a generation ago to believe that Sister had no hair, no legs, and no biological parents, for example.

Habit scholar Rebecca Sullivan notes that although the habit might seem like a static uniform, it has reacted to social and moral changes throughout history. It is a creative and imaginative clothing carefully constructed to impart meanings to its observers. It has also been used to instill unquestioning conformity and an identity that absorbs the self into a collective whole. Sometimes the habit replicated the clothing of the foundress of the community. It might have been designed by a bishop, or revealed in a mystical vision, or simply evolved from the peasant garb of the times. The habit embodied the mission of an order, joining together groups of women across the globe and across centuries in a common creative purpose.2

Today many people may not realize that sisters in North America who wear the habit are an exception rather than the norm. Most nuns say they have chosen to move to secular dress to serve their constituency better. But for some it has been a matter of personal autonomy, an emergence of the individual, and a reshaping of religious life. These sisters believe that secular clothing allows them to be approached as a "who" rather than a "what." Although public identifiability has long been a practice and law of the Church, they feel that the benefits gained from shedding the habit more than justify the change of attire. Some women religious have retained a symbolic ring or pendant, while others appear quite indistinguishable from laywomen, lipstick and jewelry included. But while it may seem that these sisters have become "invisible" on the streets and in parishes, they believe their actions are speaking louder than any physical symbols. And one nun notes, "They can still tell who we are. Our hair is too short, our skirts are too long, our shoes are too flat."3

It is this particular image to which many in the laity object. They do not want to see their cherished sisters as dumpy or unattractive--their plainness seems too close to the ordinary. Bonds formed with nuns in past generations were intensely visual and are not given up easily. Catholics cling to black-and-white memories of swishing skirts and tinkling rosary beads in the classroom and the kindly faces framed in fluted linen in hospital rooms. One contemporary Englishwoman reminisces, "I still have fond memories of the Faithful Companions of Jesus, at my old school, setting out in the sun and wearing floral sunbonnets over their black ones." She remembers the clothing long after she has lost connection to the person.

With their rapid disappearance, images of habit-clothed nuns have become more idealized and romanticized than ever. They are often used in the media and entertainment industries to grab attention and to sell products. Nuns in habit are irresistible subjects for journalists and advertisers, and this representation has become both piously saccharine and crassly kitsch at the same time. Cultural historian Jessica Matthews notes, "Items that can be found in specialty gift shops include nun squeaky toys, nun candles, nun puppets, nun lunchboxes, nun Halloween costumes, windup jumping nuns, strings of nun lights, postcards, comic books (Warrior Nun Areala), dolls, bookends, and coffee mugs that say 'It's a bad HABIT.' "4 Additionally, the Internet teems with pornographic nun-related merchandise.

Most women religious--those who wear the habit and those who don't--are not happy about this phenomenon, which either perpetuates negative and inaccurate stereotypes or denigrates the sacred. The image of the cranky old nun in habit is one often utilized by cartoonists in the secular media, but its continued appearance in diocesan newspapers boggles sisters' minds. In September 2001 The New World, the newspaper of the Archdiocese of Chicago, ran an ad featuring a cartoon nun wielding a ruler. Many sisters protested, resulting in the subsequent printing of a halfhearted apology from the editor. On the other hand, some Catholic newspapers revere the habit so seriously that they refuse to feature photographs of sisters wearing secular clothing. This rankles women religious across the board.

These phenomena are not limited to religious publications. Bridget Brewster, director of Communication and Development for the Sisters of St. Joseph of Tipton, Indiana, tells of an experience with her local media:

Following up a press release, the local newspaper sent a writer to do a story about the Sisters and particularly about St. Joseph Center and its use as a conference center and home for lay residents as well as Sisters. As is customary, a photographer was dispatched. I talked with the photographer at length. . . . "Please be respectful as you photograph individuals. It is my sincere hope that your photos will be an accurate and honest portrayal of the Sisters. These women are all about justice issues as well as their various ministries. Yes, they do gather for prayer daily as well as for Mass, however, that does not define them. Only two Sisters still wear a modified habit and veil and are not an accurate reflection of the Congregation. Please don't let me open the Sunday paper to find an 'icon of a nun in prayer.' " . . . The photographer understood and agreed. Well, as you have guessed, the large photo on the front page was one of the two Sisters in habit with a crucifix in the background! It is just too easy to convey a message with a veil and crucifix! . . . People simply do not want to let go of the image of the silly, innocent, naive, pure, helpless nun that is seen through the habit.

The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights was founded in 1973 by the late Father Virgil C. Blum, SJ. The Catholic League defends the right of Catholics--lay and clergy alike--to participate in American public life without defamation or discrimination. The League believes that Catholic-bashing has become commonplace in American society and regularly tracks negative images of nuns and the habit. For instance, in 1997 a coffeehouse in Nashville, Tennessee, sold a cinnamon bun designed to bear a likeness of Mother Teresa, called the "Nunbun," along with other products bearing her image. After protest from the League, the line was discontinued. In 1999 Late Night with Conan O'Brien kicked off the New Year with the host approaching an actress dressed as a Catholic nun and punching her in the face. That same year the League cited a Saturday Night Live episode featuring Rosie O'Donnell and Penny Marshall playing buffoon nuns in habit, with Marshall drinking liquor from a flask.

One of the most egregious objects of the League's protests is the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a group of habit-dressed gay male political activists and performers. Established in the heart of San Francisco's Castro neighborhood in 1979, the male "sisters" commit as individuals to vows of community service and strive to "promulgate universal joy and expiate stigmatic guilt through habitual manifestation." League president William Donohue has petitioned the Internal Revenue Service to revoke the tax-exempt status of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, explaining that: "If a group of anti-Semites were to dress as Shylock and mocked Jews, no one would excuse them because a small part of what they do is to contribute a pittance to selective charities."5 The "sisters' " response to those who ask them why they "make fun of nuns" is that "We are nuns, who continue the essential work of traditional sisters in nontraditional ways."

The habit was an object of satire in secular art and literature even in medieval times. Today, however, no portrayal of nuns frustrates Catholic sisters more than those in the 1992 film Sister Act. In the film, Whoopi Goldberg plays a Reno singer on the run from her gangster boyfriend. She hides in an urban convent, disguised as a habit-clad nun. The juxtaposition of a lounge performer and a convent is a formula that propelled Sister Act into becoming one of the hundred top-grossing films in the United States of all time. It greatly offended many nuns, not so much because of Goldberg's character but because of the portrayal of the convent nuns, who were depicted as naive and incompetent. It is a dated yet prevalent image that completely distorts what nuns really are like. Many women religious feel that Sister Act served to reinforce early stereotypes, such as those presented in The Bells of St. Mary's and The Sound of Music, perpetuating inaccurate perceptions of their lives formed in past generations. They believe these cliched images of the habit have made them seem an anachronism precisely at a time when their contributions to society are so relevant.

Nonetheless, the habit sells. Belgian Sister Luc-Gabrielle, reluctantly stage-named Soeur Sourire (Sister Smile) by record promoters, had a blockbuster hit with "Dominique" in 1963. Clad in her white Dominican habit, the "Singing Nun," whose birth name was Jeanine Deckers, reached number one on the American charts, superseding even the Kingsmen's "Louie Louie." The image of a singing nun in habit was so appealing that in 1965 MGM made a musical film about her called The Singing Nun, starring Debbie Reynolds. Ironically, Sister Luc-Gabrielle later wrote a song in 1967 that included these lyrics: To live in their midst consecrated, In shorts or dresses, blue jeans or pajamas.6

More than thirty years later, her wish has yet to come true. "The meaning of the habit shifts as the symbol is processed out of religious context and into a mass media image," says Sister Beth Murphy, OP, who has written on the topic and serves as communication coordinator for the Dominican Sisters of Springfield, Illinois. "Media images of priests and religious don't happen in a vacuum. They are complex social and cultural texts that carry diverse layers of meaning, subtly influenced by social and historical factors, among them, the experiences of real Catholic people." In 1965 nuns taught 30 to 40 percent of American Catholic schoolchildren.7 Sister Beth theorizes that perhaps the proliferation of the habit image in the media is more about touching the hearts of this affluent and educated market segment and less about anti-Catholicism or misinformation. Baby boomer Catholics want to see the image of the nun in habit, a distinct memory from their childhood. IBM recently cashed in with a commercially successful ad campaign featuring old-world Czechoslovakian nuns. In 2000 Jell-O ads depicted a sister in a traditional habit, licking her lips and staring longingly at a cup of pudding, with the tag line "I could go for something." Recently the noted purveyor of collectibles The Franklin Mint issued a commemorative plate showing nuns in black-and-white habits herding identically colored cattle through a field. The plate was titled "Holy Cow."8

In 1995 eighty women religious communications professionals formed the National Communicators Network for Women Religious (NCNWR) to address the image of sisters in the media. Other groups, such as Media Images of Religious Awareness (MIRA) and Sisters United News (SUN), also formed to try to change society's outdated and inaccurate perception of nuns. They believe that, beside the fact that few American sisters wear habits, the ideas of the unworldly, childlike nun incapable of managing her life, the tyrannical school nun, and the holier-than-thou nun all need reshaping.

Many sisters view Susan Sarandon's portrayal of Sister Helen Prejean in the film Dead Man Walking as a breakthrough, believing themselves accurately depicted in the media for the first time. Sister Helen relates that she had to explain to the film's director, Tim Robbins, that the nuns in her community, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Medaille, do not wear habits and were not originally required to do so by their seventeenth-century founder. She was adamant that her character be portrayed accurately, which included Sarandon's plain haircut and lack of makeup.9 Many women religious were overjoyed with the film, honoring both Sister Helen and Susan Sarandon for their work. Similarly, MIRA chose to honor Ann Dowd for her nonhabited portrayal of Sister Maureen Peabody in the award-winning television series Nothing Sacred.

But what about nuns who do wear habits? Mother Teresa of Calcutta, art critic Sister Wendy Beckett, and cable television personality Mother Angelica are figures whose contemporary image has been fixed in the public mind partly through their clothing. These women command respect and admiration in religious and secular circles alike. Perhaps the habit has even furthered their causes. Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity are the fastest-growing order of women religious in the world, and Mother Angelica's Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN) has become the largest religious media network in the world, transmitting programming to more than 79 million homes in eighty-one countries. In these cases, the habit is an empowering, positive symbol, and it is quite hard to imagine any other clothing that can make this kind of a statement.

Although the habit is essentially humble clothing with a simple mission, many complexities are woven into the fabric. Like the vividly colored badges worn by seventeenth-century Mexican religious sisters, the clothing of Catholic nuns is not simply a black-and-white matter. The habit is a metaphor for the Catholic Church itself, subject to the human extremes of love and hatred.

CHAPTER 2

From the Hardcover edition.

Enigma

A Catholic sister wearing religious garb can board a city bus and not be surprised if the bus driver places his hand over the fare box, insisting she ride free of charge. Respect for the habit remains universal--nun imposters who panhandle in city subways bank on wearing it to collect as much as $600 per day. It also can be an easy target for lampooning--consider the popular "Fighting Nun" puppet or the "Nunzilla" windup toy.1

The nun's habit is one of the most widely known and recognizable religious symbols of our time, an icon deeply embedded in our cultural consciousness. Perhaps the habit has continued to fascinate us because of its unique blend of associations. As memoirist Mary Gordon recently wrote, "The image, the idea, of a nun brings together three powerful elements: God, women, and sex."

At the same time that the habit serves to shroud the body and to mask the individual, it also dramatically announces its wearer to the world. The habit has the glamour of fashion while being antifashion; it is the antithesis of extravagance and sexual allure, yet it impresses and arouses. The sighting of a nun in habit remains for most of us a notable event, because what the habit proclaims is something so counterculture and so radical, we cannot help but to react with awe and reverence or with suspicion and disdain. From this clothing, we immediately recognize a woman who has decided to commit her life fully to God, to renounce the possibility of bearing children, and to work within the boundaries of a community for some specific sacred purpose, frequently in neglected or controversial areas. She seems both less than female but greater than human--it was not unusual for schoolchildren of only a generation ago to believe that Sister had no hair, no legs, and no biological parents, for example.

Habit scholar Rebecca Sullivan notes that although the habit might seem like a static uniform, it has reacted to social and moral changes throughout history. It is a creative and imaginative clothing carefully constructed to impart meanings to its observers. It has also been used to instill unquestioning conformity and an identity that absorbs the self into a collective whole. Sometimes the habit replicated the clothing of the foundress of the community. It might have been designed by a bishop, or revealed in a mystical vision, or simply evolved from the peasant garb of the times. The habit embodied the mission of an order, joining together groups of women across the globe and across centuries in a common creative purpose.2

Today many people may not realize that sisters in North America who wear the habit are an exception rather than the norm. Most nuns say they have chosen to move to secular dress to serve their constituency better. But for some it has been a matter of personal autonomy, an emergence of the individual, and a reshaping of religious life. These sisters believe that secular clothing allows them to be approached as a "who" rather than a "what." Although public identifiability has long been a practice and law of the Church, they feel that the benefits gained from shedding the habit more than justify the change of attire. Some women religious have retained a symbolic ring or pendant, while others appear quite indistinguishable from laywomen, lipstick and jewelry included. But while it may seem that these sisters have become "invisible" on the streets and in parishes, they believe their actions are speaking louder than any physical symbols. And one nun notes, "They can still tell who we are. Our hair is too short, our skirts are too long, our shoes are too flat."3

It is this particular image to which many in the laity object. They do not want to see their cherished sisters as dumpy or unattractive--their plainness seems too close to the ordinary. Bonds formed with nuns in past generations were intensely visual and are not given up easily. Catholics cling to black-and-white memories of swishing skirts and tinkling rosary beads in the classroom and the kindly faces framed in fluted linen in hospital rooms. One contemporary Englishwoman reminisces, "I still have fond memories of the Faithful Companions of Jesus, at my old school, setting out in the sun and wearing floral sunbonnets over their black ones." She remembers the clothing long after she has lost connection to the person.

With their rapid disappearance, images of habit-clothed nuns have become more idealized and romanticized than ever. They are often used in the media and entertainment industries to grab attention and to sell products. Nuns in habit are irresistible subjects for journalists and advertisers, and this representation has become both piously saccharine and crassly kitsch at the same time. Cultural historian Jessica Matthews notes, "Items that can be found in specialty gift shops include nun squeaky toys, nun candles, nun puppets, nun lunchboxes, nun Halloween costumes, windup jumping nuns, strings of nun lights, postcards, comic books (Warrior Nun Areala), dolls, bookends, and coffee mugs that say 'It's a bad HABIT.' "4 Additionally, the Internet teems with pornographic nun-related merchandise.

Most women religious--those who wear the habit and those who don't--are not happy about this phenomenon, which either perpetuates negative and inaccurate stereotypes or denigrates the sacred. The image of the cranky old nun in habit is one often utilized by cartoonists in the secular media, but its continued appearance in diocesan newspapers boggles sisters' minds. In September 2001 The New World, the newspaper of the Archdiocese of Chicago, ran an ad featuring a cartoon nun wielding a ruler. Many sisters protested, resulting in the subsequent printing of a halfhearted apology from the editor. On the other hand, some Catholic newspapers revere the habit so seriously that they refuse to feature photographs of sisters wearing secular clothing. This rankles women religious across the board.

These phenomena are not limited to religious publications. Bridget Brewster, director of Communication and Development for the Sisters of St. Joseph of Tipton, Indiana, tells of an experience with her local media:

Following up a press release, the local newspaper sent a writer to do a story about the Sisters and particularly about St. Joseph Center and its use as a conference center and home for lay residents as well as Sisters. As is customary, a photographer was dispatched. I talked with the photographer at length. . . . "Please be respectful as you photograph individuals. It is my sincere hope that your photos will be an accurate and honest portrayal of the Sisters. These women are all about justice issues as well as their various ministries. Yes, they do gather for prayer daily as well as for Mass, however, that does not define them. Only two Sisters still wear a modified habit and veil and are not an accurate reflection of the Congregation. Please don't let me open the Sunday paper to find an 'icon of a nun in prayer.' " . . . The photographer understood and agreed. Well, as you have guessed, the large photo on the front page was one of the two Sisters in habit with a crucifix in the background! It is just too easy to convey a message with a veil and crucifix! . . . People simply do not want to let go of the image of the silly, innocent, naive, pure, helpless nun that is seen through the habit.

The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights was founded in 1973 by the late Father Virgil C. Blum, SJ. The Catholic League defends the right of Catholics--lay and clergy alike--to participate in American public life without defamation or discrimination. The League believes that Catholic-bashing has become commonplace in American society and regularly tracks negative images of nuns and the habit. For instance, in 1997 a coffeehouse in Nashville, Tennessee, sold a cinnamon bun designed to bear a likeness of Mother Teresa, called the "Nunbun," along with other products bearing her image. After protest from the League, the line was discontinued. In 1999 Late Night with Conan O'Brien kicked off the New Year with the host approaching an actress dressed as a Catholic nun and punching her in the face. That same year the League cited a Saturday Night Live episode featuring Rosie O'Donnell and Penny Marshall playing buffoon nuns in habit, with Marshall drinking liquor from a flask.

One of the most egregious objects of the League's protests is the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a group of habit-dressed gay male political activists and performers. Established in the heart of San Francisco's Castro neighborhood in 1979, the male "sisters" commit as individuals to vows of community service and strive to "promulgate universal joy and expiate stigmatic guilt through habitual manifestation." League president William Donohue has petitioned the Internal Revenue Service to revoke the tax-exempt status of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, explaining that: "If a group of anti-Semites were to dress as Shylock and mocked Jews, no one would excuse them because a small part of what they do is to contribute a pittance to selective charities."5 The "sisters' " response to those who ask them why they "make fun of nuns" is that "We are nuns, who continue the essential work of traditional sisters in nontraditional ways."

The habit was an object of satire in secular art and literature even in medieval times. Today, however, no portrayal of nuns frustrates Catholic sisters more than those in the 1992 film Sister Act. In the film, Whoopi Goldberg plays a Reno singer on the run from her gangster boyfriend. She hides in an urban convent, disguised as a habit-clad nun. The juxtaposition of a lounge performer and a convent is a formula that propelled Sister Act into becoming one of the hundred top-grossing films in the United States of all time. It greatly offended many nuns, not so much because of Goldberg's character but because of the portrayal of the convent nuns, who were depicted as naive and incompetent. It is a dated yet prevalent image that completely distorts what nuns really are like. Many women religious feel that Sister Act served to reinforce early stereotypes, such as those presented in The Bells of St. Mary's and The Sound of Music, perpetuating inaccurate perceptions of their lives formed in past generations. They believe these cliched images of the habit have made them seem an anachronism precisely at a time when their contributions to society are so relevant.

Nonetheless, the habit sells. Belgian Sister Luc-Gabrielle, reluctantly stage-named Soeur Sourire (Sister Smile) by record promoters, had a blockbuster hit with "Dominique" in 1963. Clad in her white Dominican habit, the "Singing Nun," whose birth name was Jeanine Deckers, reached number one on the American charts, superseding even the Kingsmen's "Louie Louie." The image of a singing nun in habit was so appealing that in 1965 MGM made a musical film about her called The Singing Nun, starring Debbie Reynolds. Ironically, Sister Luc-Gabrielle later wrote a song in 1967 that included these lyrics: To live in their midst consecrated, In shorts or dresses, blue jeans or pajamas.6

More than thirty years later, her wish has yet to come true. "The meaning of the habit shifts as the symbol is processed out of religious context and into a mass media image," says Sister Beth Murphy, OP, who has written on the topic and serves as communication coordinator for the Dominican Sisters of Springfield, Illinois. "Media images of priests and religious don't happen in a vacuum. They are complex social and cultural texts that carry diverse layers of meaning, subtly influenced by social and historical factors, among them, the experiences of real Catholic people." In 1965 nuns taught 30 to 40 percent of American Catholic schoolchildren.7 Sister Beth theorizes that perhaps the proliferation of the habit image in the media is more about touching the hearts of this affluent and educated market segment and less about anti-Catholicism or misinformation. Baby boomer Catholics want to see the image of the nun in habit, a distinct memory from their childhood. IBM recently cashed in with a commercially successful ad campaign featuring old-world Czechoslovakian nuns. In 2000 Jell-O ads depicted a sister in a traditional habit, licking her lips and staring longingly at a cup of pudding, with the tag line "I could go for something." Recently the noted purveyor of collectibles The Franklin Mint issued a commemorative plate showing nuns in black-and-white habits herding identically colored cattle through a field. The plate was titled "Holy Cow."8

In 1995 eighty women religious communications professionals formed the National Communicators Network for Women Religious (NCNWR) to address the image of sisters in the media. Other groups, such as Media Images of Religious Awareness (MIRA) and Sisters United News (SUN), also formed to try to change society's outdated and inaccurate perception of nuns. They believe that, beside the fact that few American sisters wear habits, the ideas of the unworldly, childlike nun incapable of managing her life, the tyrannical school nun, and the holier-than-thou nun all need reshaping.

Many sisters view Susan Sarandon's portrayal of Sister Helen Prejean in the film Dead Man Walking as a breakthrough, believing themselves accurately depicted in the media for the first time. Sister Helen relates that she had to explain to the film's director, Tim Robbins, that the nuns in her community, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Medaille, do not wear habits and were not originally required to do so by their seventeenth-century founder. She was adamant that her character be portrayed accurately, which included Sarandon's plain haircut and lack of makeup.9 Many women religious were overjoyed with the film, honoring both Sister Helen and Susan Sarandon for their work. Similarly, MIRA chose to honor Ann Dowd for her nonhabited portrayal of Sister Maureen Peabody in the award-winning television series Nothing Sacred.

But what about nuns who do wear habits? Mother Teresa of Calcutta, art critic Sister Wendy Beckett, and cable television personality Mother Angelica are figures whose contemporary image has been fixed in the public mind partly through their clothing. These women command respect and admiration in religious and secular circles alike. Perhaps the habit has even furthered their causes. Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity are the fastest-growing order of women religious in the world, and Mother Angelica's Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN) has become the largest religious media network in the world, transmitting programming to more than 79 million homes in eighty-one countries. In these cases, the habit is an empowering, positive symbol, and it is quite hard to imagine any other clothing that can make this kind of a statement.

Although the habit is essentially humble clothing with a simple mission, many complexities are woven into the fabric. Like the vividly colored badges worn by seventeenth-century Mexican religious sisters, the clothing of Catholic nuns is not simply a black-and-white matter. The habit is a metaphor for the Catholic Church itself, subject to the human extremes of love and hatred.

CHAPTER 2

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"…Kuhns does a workman-like job of taking readers back to the habit's early origins, through its myriad medieval variations and up to its conflicted present."

--Publisher’s Weekly

"The author evenhandedly offers historical context and careful explanations . . . This readable overview is recommended for public and academic libraries."

--Library Journal

"A revelatory work that 'opens the nun’s closet doors for the first time,' then scans the contents for all their historical and symbolic associations."

--Kirkus Reviews

"…the door to the sister's closet has swung open..."

--Buffalo News

"…Elizabeth Kuhns' book about the history and culture of the habit is a sheer delight, wonderfully informative…."

--The Catholic Review

"An original, informative and engaging work…."

--The Catholic Advocate

"Fascinating details fill the book…."

--Our Sunday Visitor

"A welcome and important contribution to the literature on a sensitive subject that often inspires more heat than light."

--Margaret Susan Thompson, Professor of History, Syracuse University

"Elizabeth Kuhns’ readable account chronicles the development of the habit, while pointing to the important witness of the veil in the future.... Bravo."

--Raymond Arroyo, News Director, EWTNews

From the Hardcover edition.

--Publisher’s Weekly

"The author evenhandedly offers historical context and careful explanations . . . This readable overview is recommended for public and academic libraries."

--Library Journal

"A revelatory work that 'opens the nun’s closet doors for the first time,' then scans the contents for all their historical and symbolic associations."

--Kirkus Reviews

"…the door to the sister's closet has swung open..."

--Buffalo News

"…Elizabeth Kuhns' book about the history and culture of the habit is a sheer delight, wonderfully informative…."

--The Catholic Review

"An original, informative and engaging work…."

--The Catholic Advocate

"Fascinating details fill the book…."

--Our Sunday Visitor

"A welcome and important contribution to the literature on a sensitive subject that often inspires more heat than light."

--Margaret Susan Thompson, Professor of History, Syracuse University

"Elizabeth Kuhns’ readable account chronicles the development of the habit, while pointing to the important witness of the veil in the future.... Bravo."

--Raymond Arroyo, News Director, EWTNews

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

More than just an eye-opening study of the symbolic significance of starched wimples, dark dresses, and flowing veils, "The Habit" is an incisive, engaging portrait of the roles nuns have played in the Catholic Church and in ministering to the spiritual and social needs of society.