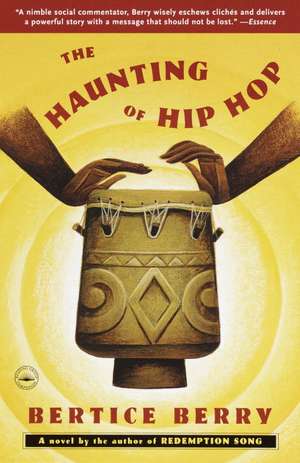

The Haunting of Hip Hop

Autor Bertice Berryen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

In ancient West Africa, the drum was more than a musical instrument, it was a vehicle of communication–it conveyed information, told stories, and passed on the wisdom of generations. The magic of the drum remains alive today, and with her magnificent second novel, Berry brings those powerful beats to the streets of Harlem.

Harry “Freedom” Hudson is the hottest hip hop producer in New York City, earning unbelievable fees for his tunes and the innovative sound that puts his artists on the top of the charts. Harry is used to getting what he wants, so when he’s irresistibly drawn to a house in Harlem, he assumes he’ll be moving in as soon as the papers can be drawn up. The house, after all, has been abandoned for years. Or has it?

Rumors are rife in the neighborhood that the house is haunted; that mysterious music, shouts, and sobbing can be heard late at night. Ava, Harry’s strong-willed, no-nonsense agent, dismisses it all as “old folks” tales–until she opens the door and finds an eerie, silent group of black people, young and old, gathered around a man holding an ancient African drum. They are waiting for Harry and bear a warning that touches his very soul: “We gave the drum back to your generation in the form of rap, but it’s being used to send the wrong message.”

The Haunting of Hip Hop is a reminder of the importance of honoring the past as a means of moving safely and firmly into the future. It is sure to raise eyebrows and stir up controversy about the impact, good and bad, of rap culture.

Preț: 90.52 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.33€ • 18.83$ • 14.56£

17.33€ • 18.83$ • 14.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767912129

ISBN-10: 0767912128

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 135 x 221 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Harlem Moon

ISBN-10: 0767912128

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 135 x 221 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Harlem Moon

Notă biografică

BERTICE BERRY is a comedian and inspirational speaker and holds a Ph.D. in sociology. She has about two hundred speaking engagements per year.. She is the author of two novels (Redemption Song and The Haunting of Hip Hop) and four works of nonfiction. She lives in southern California, where she is raising her sister’s three children.

Extras

prologue

No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at least finding

the other end of it about his own neck.

–The L i fe a n d T i m e s o f Fre d e r i ck D o u gl a s s, 1 8 8 1

Ngozi sat behind his wife, Bani. His legs were wrapped around hers. She leaned back, and he rubbed her large belly. “She will deliver soon,” his mother said. Ngozi nibbled Bani’s ear and then whispered into it. “We will have joy. Don’t worry.” His wife had wept for most of her pregnancy. She felt that something terrible was going to happen. Ngozi tried to persuade Bani differently. On nights like this one, calm and still, Ngozi would rub her belly and speak to his unborn son. “Yo Tayembé. Yo Tayembé, and then you say ‘Ye oh Ye Ba Ba,’ ” he said to Bani’s stomach.

Bani laughed when Ngozi first did this. “The child cannot hear you, and you know he cannot respond.”

“Yo Tayembé, I’m calling you, son. ‘Ye oh Ye Ba Ba. I hear you, Papa,’ ” he said again. “How do you know he cannot hear me?” Ngozi asked.

“How do you know it’s a boy?” his wife responded.

“Woman,” Ngozi said playfully, “did I not tell you that you would be my wife? Did I not tell you that I would bring you happiness? Have I been wrong? I also told you that you were with child. I knew the moment it happened.”

Bani laughed. “Your mother was right to give you a woman’s name. You have the thoughts of a woman.”

Ngozi smiled. He’d heard this many times before. Never was he offended. “Yo Tayembé. Yo Tayembé,” he called to the child. “Someday you’ll answer me and my stubborn wife. Bani, you’ll remember this moment.”

Bani was soon lulled into a sweet sleep. She would not wake up and feel Ngozi’s arms wrapped tightly around her as she had on past mornings. Instead she would come to know the reason why she had been crying. Her husband, her love, would be gone from her forever.

When Ngozi saw that Bani was deeply asleep, he quietly moved himself from their embrace. He had to find the piece of wood his mother told him to look for. He had to make the drum for his unborn son. But he was making it for the son he would never see.

The drum had always been important to his people, but this one would be special. It had to be. Ngozi’s mother had told him everything she had seen. Her visions started on the day he was born. On that day the memory of her grandfather appeared to her. “Name him Ngozi, for he will be a blessing.”

Ngozi’s mother laughed and said, “The others will think me crazy. Ngozi is a name for a girl child, she who is a blessing.”

“Yes,” the spirit memory of her grandfather said. “He will be a blessing, but he has been chosen to give birth.” And then he was gone.

His mother had many visions after this one, but the last one, the most important one, she shared with him just before he was captured. She told him how to make the drum, what materials to use, and when to use them. The drum would be the last thing he made. “You will make this drum for your son, but you will not see him play it,” she said. “Your life here will be short, but your task is great. The drum will keep you connected to your people and your purpose. You must do it, son, and you must do it right.”

Ngozi was searching for just the right piece of wood for the body of the drum. Just as he bent down to touch the hollowed log that almost spoke his name, he heard something behind him. Before he could turn to see what it was, Ngozi was attacked by human hands, connected to an unnatural evil. He was carried away into the thing that his mother had spoken of. Some called it slavery; he called it death. Unfortunately for Ngozi’s son, and many sons to follow, the magic of his drum would not be heard. It would be several generations before that power would be felt. Once that drum was found and played, however, it would send the wrong message.

Chapter 1

The Birth of Freedom

And before I be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave and go home to my Lord and be Free.

–Neg ro s p i r i t u a l

Harry “Freedom” Hudson saw the old house and wondered why it had come to mean so much to him. He’d driven by this place many times, and it always reached out to him and called him back. Something in the boarded up corner house wanted him there, even in the midst of all the gentrification and the onslaught of yuppies. It was white flight in reverse. The park across from the brownstone was filled with children, mostly white; an odd thing in Harlem. Harlem belonged to him, to his people now. As he slowed and pulled up to the curb, he had a feeling that one day he’d own this house. What he didn’t know was that this brownstone would come to own him.

Freedom, as he was known by the hip-hop world, was born Harry Hudson on the coldest October night New York had experienced in over one hundred years. “I’m not going to let the Devil steal my joy,” his mother, Earlene, had said as she tried to start the engine of her old Chevy. The pain came suddenly and passed just as quickly. By the time she reached the hospital, she could feel Harry trying to make his way here. She drove up to the emergency room, blowing her horn and screaming in the Southern accent that had long been replaced by Brooklynese. The emergency room attendants who ran out to help her were shocked to see the crown of the boy’s head on her seat.

“That boy always knew how to make his own way,” Harry’s mother would say later.

Harry never knew his father, and was raised by his mother and grandmother, who instilled in him a fierce independence. As a young boy, Harry always felt, even if it was not apparent to those around him, that he’d been born to do something major. He had no idea what that something was, but he knew he had to be ready. Thankfully, he was good at just about everything he put his hands to. Not just good; he mastered any area of study quickly, but he got tired of it quickly, too.

Harry finally found his “freedom” in music as a hip-hop producer, and it was his style, or “stylo” as he called it, that everyone wanted. Freedom was being pulled in so many directions now that he had little time to create. But he wasn’t convinced that the record companies truly wanted or understood his creativity. They just wanted more of what had made them rich and him famous; the phat sound that put all of his artists on the charts and brought renewed prestige to a sinking music corporation. KMB Records paid him the crazy fees he asked for. Freedom laughed at the fact that his fees were based on whether or not he wanted a job. If he didn’t really want the work, he charged a higher price. He’d gotten joy out of charging mad fees for tunes he made up on the spot and rejoiced when he charged people who didn’t remember that they’d once told him he would never get work in the recording industry. When he first started out, he heard every rejection for every reason possible.

Initially, the industry people told Freedom that his sound was too repetitive, then they said his music didn’t have a hook. After a while, Freedom ignored the criticism and just did what he felt. “Go with your heart,” his mother had always told him. And it worked almost all of the time. Almost.

Freedom had many women in his life, but he only allowed his mother and grandmother into his heart. To say that Freedom was unlucky in love would be like saying Phyllis Hyman could sing. Both statements were true, but were grossly understated. Phyllis Hyman did more than sing. She ripped out your heart with every note and phrase. Phyllis made you feel all her sadness, and she made you feel like it was yours. But she warned you just the same. “Be Careful How You Use My Love” was the song Freedom thought of whenever he thought about the concept of love. There was a wall around his heart that was as ancient as the pain of black men. He wore that wall like a stick on a kid’s shoulder, daring anyone bad enough to knock it off. Freedom loved women; he just didn’t know how to be in love with them. He’d allowed himself to fall in love once, a very long time ago, but had no intention of making that mistake again.

Freedom was raised by women before psychologists had a chance to declare that not having a father was dysfunctional. For Freedom, it was heaven and he loved the balance provided by his mother and grandmother. Still, something was missing.

Shy, self-conscious, and an only child, Harry had very few playmates, so he filled the gap by creating his own imaginary ones. But to Harry these playmates sometimes seemed real, like long-gone relatives come back to play.

His grandmother was never bothered by these “playmates,”but his mother didn’t like it. “Stop talking to yourself, son, and go out and play,” she’d tell him.

“Leave him alone, gal,” his grandmother would argue, “he’s talking to his people.”

Sometimes at his mother’s request, Harry would try to shut out the voices he heard--deep, lilting voices that told him stories and sang him songs. One day a voice called him to the window.

“Yo Tayembé,” he heard the voice say. Harry didn’t know the meaning of these words. They sounded familiar to him, but he couldn’t exactly remember where he’d heard them.

“Yo Tayembé,” the voice said again. Young Harry walked toward the window looking for the source of the voice, but didn’t see anyone. He climbed into the window seat and threw open the window and stuck his head out. Still, he saw nothing. Quietly but suddenly a wave of sadness enveloped him, and he began to cry.

“Where is my father?” Harry said aloud. Just as he said this, his mother entered the room. “Where is my father?” he repeated as he turned to her from the window seat.

“He’s gone and he’s been gone for a long time. Now come down from there,” she said, trying to remain calm.

Harry wanted to do what his mother said, but became dizzy and lost his footing. His mother rushed to him and pulled him back in. “Ye oh Ye Ba Ba,” he chanted before losing consciousness.

From then on Harry’s mother forbade even the mention of an invisible playmate. Earlene argued for days with her mother, before she told her about the incident at the window. Harry’s grandmother responded as Earlene assumed she would, by going into a mode of prayer and fasting, saying that little Harry was under spiritual attack. Finally, though his grandmother was too proud to verbalize it, she silently relented and decided to go along with her daughter. Grandma would no longer indulge her grandson and his belief in his imaginary playmates.

Around this time Harry started communicating without speaking. He would play drumbeats on any surface with any object. In school he’d use his pencil and beat out rhythms on his notebook. At first, he played so softly that no one noticed. But the playing was accompanied by what appeared to be daydreaming, and it grew louder.

“Hey, Little Drummer Boy,” his fifth-grade teacher yelled. The entire class laughed at the name and began to use it with a vengeance as children do. “Drummer” was slowly replaced with “Dumber,” and so he was known throughout his school career as the “Dumber Boy,” which put him just above the most unpopular boy who everyone called “Stinkweed.”

Despite his nickname, Harry continued to play his beats, luxuriating in the steady waves of music ever present in his head. One day he felt the rhythm in his heart swirl and dash whenever a certain little girl was around. Stacey Brown. For days he let her name move around in his brain, dancing in be-tween beats. Stacey–“ba ding ding”–Brown, he would think, was cute–“ra dat dat”–smart, and popular. He didn’t care that the

main reason the other boys liked her was because she developed early.

“Hey, Harry,” she whispered as she passed him one day in the hall. He usually heard his name from older adults, rarely from children, so when she spoke to him, he couldn’t believe it, and couldn’t respond. For weeks after Stacey first said his name, the shy Harry allowed himself to dream about what he’d overheard other boys say they were doing with girls. Harry imagined what it would feel like to kiss Stacey and touch her all over. Then he imagined doing “it.”

Finally, after a great deal of mental preparation, Harry worked up the nerve to ask Stacey to the movies. He approached her at the end of their sixth-period class. “Stacey,” he stammered, “would you ...would you . . .” Harry was so taken with her he was unable to complete his sentence. Instead, he began to tap out beats on the books he’d been holding.

Stacey had liked Harry, but popular girls like to stay popular. Talking to Harry when no one was looking was one thing, but just as he began to drum, a group of her friends walked up and created within her the need to be nasty. “Spit it out Drummer Boy, or should I say Dumber Boy?” and without any concern for Harry’s feelings, she ran off.

Harry stood frozen in the hall, and remained in the same spot until the school building closed. During those painful two hours, Harry made plans to take revenge on Stacey and all the other women he would ever come into contact with. “Someday, they’re gonna want to be with me, and I’ll be the one to run away.”

It would take Freedom his entire life to realize that too often childhood wishes become the motivation for the misbehavior of adults.

No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at least finding

the other end of it about his own neck.

–The L i fe a n d T i m e s o f Fre d e r i ck D o u gl a s s, 1 8 8 1

Ngozi sat behind his wife, Bani. His legs were wrapped around hers. She leaned back, and he rubbed her large belly. “She will deliver soon,” his mother said. Ngozi nibbled Bani’s ear and then whispered into it. “We will have joy. Don’t worry.” His wife had wept for most of her pregnancy. She felt that something terrible was going to happen. Ngozi tried to persuade Bani differently. On nights like this one, calm and still, Ngozi would rub her belly and speak to his unborn son. “Yo Tayembé. Yo Tayembé, and then you say ‘Ye oh Ye Ba Ba,’ ” he said to Bani’s stomach.

Bani laughed when Ngozi first did this. “The child cannot hear you, and you know he cannot respond.”

“Yo Tayembé, I’m calling you, son. ‘Ye oh Ye Ba Ba. I hear you, Papa,’ ” he said again. “How do you know he cannot hear me?” Ngozi asked.

“How do you know it’s a boy?” his wife responded.

“Woman,” Ngozi said playfully, “did I not tell you that you would be my wife? Did I not tell you that I would bring you happiness? Have I been wrong? I also told you that you were with child. I knew the moment it happened.”

Bani laughed. “Your mother was right to give you a woman’s name. You have the thoughts of a woman.”

Ngozi smiled. He’d heard this many times before. Never was he offended. “Yo Tayembé. Yo Tayembé,” he called to the child. “Someday you’ll answer me and my stubborn wife. Bani, you’ll remember this moment.”

Bani was soon lulled into a sweet sleep. She would not wake up and feel Ngozi’s arms wrapped tightly around her as she had on past mornings. Instead she would come to know the reason why she had been crying. Her husband, her love, would be gone from her forever.

When Ngozi saw that Bani was deeply asleep, he quietly moved himself from their embrace. He had to find the piece of wood his mother told him to look for. He had to make the drum for his unborn son. But he was making it for the son he would never see.

The drum had always been important to his people, but this one would be special. It had to be. Ngozi’s mother had told him everything she had seen. Her visions started on the day he was born. On that day the memory of her grandfather appeared to her. “Name him Ngozi, for he will be a blessing.”

Ngozi’s mother laughed and said, “The others will think me crazy. Ngozi is a name for a girl child, she who is a blessing.”

“Yes,” the spirit memory of her grandfather said. “He will be a blessing, but he has been chosen to give birth.” And then he was gone.

His mother had many visions after this one, but the last one, the most important one, she shared with him just before he was captured. She told him how to make the drum, what materials to use, and when to use them. The drum would be the last thing he made. “You will make this drum for your son, but you will not see him play it,” she said. “Your life here will be short, but your task is great. The drum will keep you connected to your people and your purpose. You must do it, son, and you must do it right.”

Ngozi was searching for just the right piece of wood for the body of the drum. Just as he bent down to touch the hollowed log that almost spoke his name, he heard something behind him. Before he could turn to see what it was, Ngozi was attacked by human hands, connected to an unnatural evil. He was carried away into the thing that his mother had spoken of. Some called it slavery; he called it death. Unfortunately for Ngozi’s son, and many sons to follow, the magic of his drum would not be heard. It would be several generations before that power would be felt. Once that drum was found and played, however, it would send the wrong message.

Chapter 1

The Birth of Freedom

And before I be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave and go home to my Lord and be Free.

–Neg ro s p i r i t u a l

Harry “Freedom” Hudson saw the old house and wondered why it had come to mean so much to him. He’d driven by this place many times, and it always reached out to him and called him back. Something in the boarded up corner house wanted him there, even in the midst of all the gentrification and the onslaught of yuppies. It was white flight in reverse. The park across from the brownstone was filled with children, mostly white; an odd thing in Harlem. Harlem belonged to him, to his people now. As he slowed and pulled up to the curb, he had a feeling that one day he’d own this house. What he didn’t know was that this brownstone would come to own him.

Freedom, as he was known by the hip-hop world, was born Harry Hudson on the coldest October night New York had experienced in over one hundred years. “I’m not going to let the Devil steal my joy,” his mother, Earlene, had said as she tried to start the engine of her old Chevy. The pain came suddenly and passed just as quickly. By the time she reached the hospital, she could feel Harry trying to make his way here. She drove up to the emergency room, blowing her horn and screaming in the Southern accent that had long been replaced by Brooklynese. The emergency room attendants who ran out to help her were shocked to see the crown of the boy’s head on her seat.

“That boy always knew how to make his own way,” Harry’s mother would say later.

Harry never knew his father, and was raised by his mother and grandmother, who instilled in him a fierce independence. As a young boy, Harry always felt, even if it was not apparent to those around him, that he’d been born to do something major. He had no idea what that something was, but he knew he had to be ready. Thankfully, he was good at just about everything he put his hands to. Not just good; he mastered any area of study quickly, but he got tired of it quickly, too.

Harry finally found his “freedom” in music as a hip-hop producer, and it was his style, or “stylo” as he called it, that everyone wanted. Freedom was being pulled in so many directions now that he had little time to create. But he wasn’t convinced that the record companies truly wanted or understood his creativity. They just wanted more of what had made them rich and him famous; the phat sound that put all of his artists on the charts and brought renewed prestige to a sinking music corporation. KMB Records paid him the crazy fees he asked for. Freedom laughed at the fact that his fees were based on whether or not he wanted a job. If he didn’t really want the work, he charged a higher price. He’d gotten joy out of charging mad fees for tunes he made up on the spot and rejoiced when he charged people who didn’t remember that they’d once told him he would never get work in the recording industry. When he first started out, he heard every rejection for every reason possible.

Initially, the industry people told Freedom that his sound was too repetitive, then they said his music didn’t have a hook. After a while, Freedom ignored the criticism and just did what he felt. “Go with your heart,” his mother had always told him. And it worked almost all of the time. Almost.

Freedom had many women in his life, but he only allowed his mother and grandmother into his heart. To say that Freedom was unlucky in love would be like saying Phyllis Hyman could sing. Both statements were true, but were grossly understated. Phyllis Hyman did more than sing. She ripped out your heart with every note and phrase. Phyllis made you feel all her sadness, and she made you feel like it was yours. But she warned you just the same. “Be Careful How You Use My Love” was the song Freedom thought of whenever he thought about the concept of love. There was a wall around his heart that was as ancient as the pain of black men. He wore that wall like a stick on a kid’s shoulder, daring anyone bad enough to knock it off. Freedom loved women; he just didn’t know how to be in love with them. He’d allowed himself to fall in love once, a very long time ago, but had no intention of making that mistake again.

Freedom was raised by women before psychologists had a chance to declare that not having a father was dysfunctional. For Freedom, it was heaven and he loved the balance provided by his mother and grandmother. Still, something was missing.

Shy, self-conscious, and an only child, Harry had very few playmates, so he filled the gap by creating his own imaginary ones. But to Harry these playmates sometimes seemed real, like long-gone relatives come back to play.

His grandmother was never bothered by these “playmates,”but his mother didn’t like it. “Stop talking to yourself, son, and go out and play,” she’d tell him.

“Leave him alone, gal,” his grandmother would argue, “he’s talking to his people.”

Sometimes at his mother’s request, Harry would try to shut out the voices he heard--deep, lilting voices that told him stories and sang him songs. One day a voice called him to the window.

“Yo Tayembé,” he heard the voice say. Harry didn’t know the meaning of these words. They sounded familiar to him, but he couldn’t exactly remember where he’d heard them.

“Yo Tayembé,” the voice said again. Young Harry walked toward the window looking for the source of the voice, but didn’t see anyone. He climbed into the window seat and threw open the window and stuck his head out. Still, he saw nothing. Quietly but suddenly a wave of sadness enveloped him, and he began to cry.

“Where is my father?” Harry said aloud. Just as he said this, his mother entered the room. “Where is my father?” he repeated as he turned to her from the window seat.

“He’s gone and he’s been gone for a long time. Now come down from there,” she said, trying to remain calm.

Harry wanted to do what his mother said, but became dizzy and lost his footing. His mother rushed to him and pulled him back in. “Ye oh Ye Ba Ba,” he chanted before losing consciousness.

From then on Harry’s mother forbade even the mention of an invisible playmate. Earlene argued for days with her mother, before she told her about the incident at the window. Harry’s grandmother responded as Earlene assumed she would, by going into a mode of prayer and fasting, saying that little Harry was under spiritual attack. Finally, though his grandmother was too proud to verbalize it, she silently relented and decided to go along with her daughter. Grandma would no longer indulge her grandson and his belief in his imaginary playmates.

Around this time Harry started communicating without speaking. He would play drumbeats on any surface with any object. In school he’d use his pencil and beat out rhythms on his notebook. At first, he played so softly that no one noticed. But the playing was accompanied by what appeared to be daydreaming, and it grew louder.

“Hey, Little Drummer Boy,” his fifth-grade teacher yelled. The entire class laughed at the name and began to use it with a vengeance as children do. “Drummer” was slowly replaced with “Dumber,” and so he was known throughout his school career as the “Dumber Boy,” which put him just above the most unpopular boy who everyone called “Stinkweed.”

Despite his nickname, Harry continued to play his beats, luxuriating in the steady waves of music ever present in his head. One day he felt the rhythm in his heart swirl and dash whenever a certain little girl was around. Stacey Brown. For days he let her name move around in his brain, dancing in be-tween beats. Stacey–“ba ding ding”–Brown, he would think, was cute–“ra dat dat”–smart, and popular. He didn’t care that the

main reason the other boys liked her was because she developed early.

“Hey, Harry,” she whispered as she passed him one day in the hall. He usually heard his name from older adults, rarely from children, so when she spoke to him, he couldn’t believe it, and couldn’t respond. For weeks after Stacey first said his name, the shy Harry allowed himself to dream about what he’d overheard other boys say they were doing with girls. Harry imagined what it would feel like to kiss Stacey and touch her all over. Then he imagined doing “it.”

Finally, after a great deal of mental preparation, Harry worked up the nerve to ask Stacey to the movies. He approached her at the end of their sixth-period class. “Stacey,” he stammered, “would you ...would you . . .” Harry was so taken with her he was unable to complete his sentence. Instead, he began to tap out beats on the books he’d been holding.

Stacey had liked Harry, but popular girls like to stay popular. Talking to Harry when no one was looking was one thing, but just as he began to drum, a group of her friends walked up and created within her the need to be nasty. “Spit it out Drummer Boy, or should I say Dumber Boy?” and without any concern for Harry’s feelings, she ran off.

Harry stood frozen in the hall, and remained in the same spot until the school building closed. During those painful two hours, Harry made plans to take revenge on Stacey and all the other women he would ever come into contact with. “Someday, they’re gonna want to be with me, and I’ll be the one to run away.”

It would take Freedom his entire life to realize that too often childhood wishes become the motivation for the misbehavior of adults.

Recenzii

"A nimble social commentator, Berry wisely eschews cliches and delivers a powerful story with a message that should not be lost."

--Essence

"In this poignant and educational 'ghost' story, Berry drives home the importance of making sure the richness of ancient Africa's drums lives in the music today."

--Heart & Soul

--Essence

"In this poignant and educational 'ghost' story, Berry drives home the importance of making sure the richness of ancient Africa's drums lives in the music today."

--Heart & Soul

Descriere

Harry "Freedom" Hudson, a hot hip-hop producer, is used to getting what he wants. When he's drawn to a house in Harlem, he assumes he'll be moving in soon. Ignoring rumors the house is haunted, his agent, Ava finds an silent group of black people in the house, gathered around a man holding an ancient African drum. They've been waiting for Harry, and they bear a warning for him.