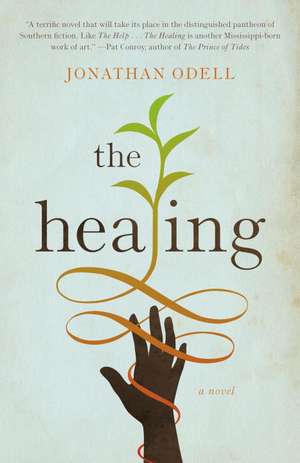

The Healing

Autor Jonathan Odellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 noi 2012

Rich in mood and atmosphere, The Healing is a powerful, warmhearted novel about unbreakable bonds and the power of story to heal.

Preț: 92.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.64€ • 18.47$ • 14.59£

17.64€ • 18.47$ • 14.59£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307744562

ISBN-10: 0307744566

Pagini: 340

Dimensiuni: 132 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307744566

Pagini: 340

Dimensiuni: 132 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Recenzii

“Compelling, tragic, comic, tender and mystical. . . . Combines the historical significance of Kathryn Stockett’s The Help with the wisdom of Toni Morrison’s Beloved.” —Minneapolis Star-Tribune

“A terrific novel that will take its place in the distinguished pantheon of Southern fiction…. Polly Shine is a character for the ages.” —Pat Conroy, author of The Prince of Tides

“A storytelling tour de force.” —Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Jonathan Odell won me over with his fresh take on an 1860's Mississippi plantation, and the connective power of story to heal body, mind and community.” —Lalita Tademy, author of Cane River

“A remarkable rite-of-passage novel with an unforgettable character. . . . The Healing transcends any clichés of the genre with its captivating, at times almost lyrical, prose; its firm grasp of history; vivid scenes; and vital, fully realized people, particularly the slaves with their many shades of color and modes of survival.” —Associated Press

“Odell gives voice to strong women at a time in history when their strength might have been their undoing. When Polly Shine's fierce knowledge comes up against Granada’s stubborn resistance, the reader is held captive as the two attempt to resolve their conflict and Granada is made to face her destiny. This moving story is a must-read for fans of historical fiction.” —Kathleen Grissom, author of The Kitchen House

“A haunting tale of Southern fiction peopled with vivid and inspiring personalities. . . . Polly Shine is an unforgettable character who shows how the power and determination of one woman can inspire and transform the lives of those around her.” —Bookreporter

“Jonathan Odell finds the right words, using the language of the day, its idiom and its music to great advantage in a compelling work that can stand up to The Help in the pantheon of Southern literature.” —Shelf Awareness

“Odell has written one of those beautiful Southern tales with unforgettable characters. Required reading.” —New York Post

“Engrossing. . . . This historical novel probes complex issues of freedom and slavery.” —Library Journal (starred review)

“When the young slave Granada Satterfield reluctantly undertakes a quest to recover her own identity, she finds that she must begin by seeking the answers to two questions: Who are my people and what are their stories? Jonathan Odell's compelling new novel The Healing is a lyrical parable, rich with historical detail and unflinching in the face of disturbing facts.” —Valerie Martin, author of Property

“Rich in character and incident.” —Publishers Weekly

“The Healing is a moving cri de coeur for all those who yearn to be free, and for the wise women among us who understand that to subjugate one person is to subjugate all of humanity."

—Robin Oliveira, author of My Name if Mary Sutter

Notă biografică

JONATHAN ODELL is the author of the acclaimed novel The View from Delphi, which deals with the struggle for equality in pre-civil rights Mississippi, his home state. His short stories and essays have appeared in numerous collections. He spent his business career as a leadership coach to Fortune 500 companies and currently resides in Minnesota.

Extras

1847

Ella was awake when she heard the first timid knock at the cabin door. Her husband, who lay beside her on the corn-shuck mattress, snored undisturbed. She kept still as well, not wanting to wake the newborn that slept in the crook of her arm. The baby had cried most of the night and had only just settled into a fitful sleep. Ella couldn’t blame the girl for being miserable. The room was intolerably hot.

Like everybody else in the quarter, Ella believed the cholera was carried by foul nocturnal vapors arising from the surrounding swamp, so she and Thomas kept their shutters and doors closed tight against the night air, doing their best to protect their daughter from the killing disease that had already taken so many.

The rapping on the door became more insistent. Ella pushed against Thomas with her foot. On the second shove he awoke with a snort.

“Thomas! See to the door,” she whispered, “and mind Yewande.”

Wearing only a pair of cotton trousers, Thomas eased himself from the bed and crossed the room. He lifted the bar and pulled open the door, but his broad muscled back blocked the visitors’ faces. From the flickering glare cast around her husband, Ella could tell one of the callers held a lantern.

“Thomas,” came the familiar voice, “get Ella up.”

Ella started at the words. It was Sylvie, the master’s cook. The woman lived all the way up at the mansion and would have no good reason to be out this time of night unless it was something bad.

“Now?” Thomas whispered. “She’s sleeping.”

“She needs to carry her baby up to the master’s house,” Sylvie said. “Ella got to make haste on it. Mistress Amanda is waiting on her.”

“What she wanting with my woman and child in the dead of night?” Ella heard the alarm rising in her husband’s voice.

“Thomas, you know it ain’t neither night nor day for Mistress Amanda. She ain’t slept a wink since the funeral. And she’s grieving particular bad tonight. Her medicine don’t calm her down no more. She ain’t in no mood to be trifled with.”

“Old Silas,” Thomas pled to another unseen caller, “you tell the mistress that Ella will come by tomorrow, early in the morning.” Then he dropped his voice to a hush. “You know the mistress ain’t right in her head.”

Old Silas had more pull than anybody with the master, but from the lack of response, Ella imagined Silas’s gray head, weathered skin stretched tight over his skull, shaking solemnly.

Thomas let go a deep breath and then turned back to his wife. Behind him, Ella could hear the talk as it continued between the couple outside.

“You know good and well she didn’t say to fetch Ella,” Old Silas whispered harshly to his wife. “Just the baby, she said. What’s in your head?”

“Shush!” Aunt Sylvie fussed. “You didn’t see what I seen. I know what I’m doing.”

Ella met them at the door holding the swaddled infant. Not yet fourteen, Ella wore a ripped cotton shift cut low for nursing, and even in the heat of the cabin, she trembled. The yellow light lit the faces of the cook and her husband.

“What she want with Yewande?” Ella whimpered. “What she going to do to my baby?”

“Ella, she ain’t going to hurt your baby,” Sylvie assured. “Mistress wouldn’t do that for the world.”

“But why—”

Old Silas reached out and laid a gentle hand on Ella’s shoulder. “I expect she wants to name your girl, is all.” His voice was firm but comforting. He spoke more like the master than any slave. “That right, Sylvie?”

“Of course!” Sylvie said, as if hearing the explanation for the first time. “I expect that’s all it is. Mistress Amanda wants to name your girl.”

“But Master Ben names the children,” Ella argued.

“You heard what the master said,” Sylvie fussed. “Things got to change. We all got to mind her wishes until she comes through this thing. No use fighting it.”

Silas’s tone was kinder. “Mistress has taken an interest in your child from the start,” he explained. “Her Becky passed the very hour your girl was born. I suppose their souls might have touched, one coming and the other leaving. No doubt that’s why the mistress thinks your child so special. Every time the mistress hears your baby cry, she asks after Yewande’s health.”

Ella pulled the child closer to her breast and set her mouth to protest.

“Ella, don’t make a fuss,” Sylvie said impatiently. “Just do what she says tonight. Anything in the world to calm her down. Nobody getting any rest until she do. Let her name your baby if she has a mind. She been taking so much medicine, she’ll forget her own name by morning.”

Ella saw the resoluteness in the faces of the couple. She finally gave a trembling nod.

As the three walked down the lane of cabins, they passed smoldering heaps of pine and cypress, attempts by the inhabitants to purify the air and keep the mosquitoes at bay. The acrid, suffocating smoke seemed to travel with the little group, enveloping them in a cloud that seared the lungs. Up in the distance, the lights in the great house came into view. No words were spoken as Sylvie, ever crisp and efficient, walked beside Ella while Silas lit the path.

It was Old Silas whom the master had first sent down to the quarters days ago with the news of Miss Becky’s death. Ella remembered how odd Silas’s little speech had been.

“Miss Becky has passed of a summer fever,” he said, “not the cholera, understand? If any of those who come to pay respects should ask you, that is what you are to say. It was a summer fever that took Miss Becky. Don’t say a word more.”

Someone had asked Silas why they had to lie. It was known to everyone on the plantation that the girl had come down with the same sickness that had killed nearly two dozen of his field hands. Sylvie had already let it be known that she had watched Miss Becky suffering in her four-poster bed, halfway to heaven on her feather mattress. Sylvie had witnessed the sudden nausea and the involuntary discharges that didn’t let up through the entire night. She had seen the girl’s eyes, once the color of new violets, go dim and sink deep into their sockets, her face looking more like that of an ancient woman exhausted by life than a twelve-year-old girl. From what Sylvie had said, Miss Becky’s dying had been no different than their own children’s.

Before answering the question, Silas jawed the chaw of tobacco to his other cheek. “He’s doing it to protect Miss Becky’s good name. Master says the cholera is not a quality disease. The highborn don’t come down with such. Especially no innocent twelve-year-old white girl.” Silas put two fingers up to his mouth and let go a stream of brown juice.

A dark laughter rippled through the survivors who stood there, all of whom had lost family or friends. What Silas wouldn’t say, Sylvie made sure the others knew. She said the master was so afraid of what his neighbors thought he had refused to send to Delphi for the doctor lest the news get out that Miss Becky had caught a sickness so foul that it was reserved for Negroes and the Irish. He had stood there and watched while the girl’s breathing became so faint it didn’t even disturb the fine linen sheet that covered her. He ranted about how Rubina, Becky’s constant companion and the daughter of a house slave, was healthy as a colt. “There is no way,” he swore, “the cholera would pass over a slave and strike down a white girl!”

Sylvie remembered the mistress’s face when her husband has said that. The cook had never seen that much agony in a white person’s eyes.

When all hope was lost, the master finally turned his back on his wife and daughter and home, leaving Becky to lie motionless, shrouded by the embroidered canopy of pink-and-white roses; Mistress Amanda to witness alone the inevitable end; and little Rubina to sob outside her dying playmate’s room. He rounded up a work gang and several bottles of whiskey, saddled his horse, and hightailed it out to the swamps to burn more Delta acreage.

“I guess that’s the white man’s way,” Sylvie had told them all, disgusted. “Lose a child, sire more land.”

That’s when the mistress’s mind finally broke. At first she wanted to have little Rubina whipped and her wounds salted, sure the girl had given her daughter the disease. But soon enough she relented. It was clear that she couldn’t hurt Becky’s friend. Mistress Amanda’s crazed search for blame finally settled on her husband. She cursed him night and day and threw china dishes against the wall. When Master Ben sent for some medicine to calm her, she swallowed all she could get her hands on. Anyway, that’s what those who worked in the house said.

Sylvie reached her arm around the young mother’s shoulder. Ella felt sure it was as much to keep her from bolting as it was to comfort her. Not that Ella hadn’t thought about running off with her baby into the darkness and hiding in the swamps, waiting out the mistress’s memory. But nobody had ever survived for more than two days out in the swamps.

Even if she did make it past two days, it was no guarantee the mistress would come to her senses. Since the day of the funeral, the mistress’s silhouette could be seen through her bedroom window at all times of night, her arms animated, her fists shaking accusingly at nobody.

Ella didn’t know what happened first, Sylvie’s grip tightening to a bruising clench or the gunshot that seemed to crack right over her head. The small procession halted and they all gazed up at the house.

“Lord, what she done now?” Sylvie said.

While they watched, Master Ben came storming down the back steps from the upstairs gallery in his nightshirt and bare feet, dragging his bed linen behind him.

“It’s about time y’all got here. She’s about to hunt you down and she’s got her daddy’s derringer.”

The group stepped aside to let him pass. “My advice,” he grumbled without looking back, “is to hurry up before she reloads.”

“God be great,” Sylvie said under her breath. “I wish she would go ahead and shoot the man so we could all get some peace.”

Ella was awake when she heard the first timid knock at the cabin door. Her husband, who lay beside her on the corn-shuck mattress, snored undisturbed. She kept still as well, not wanting to wake the newborn that slept in the crook of her arm. The baby had cried most of the night and had only just settled into a fitful sleep. Ella couldn’t blame the girl for being miserable. The room was intolerably hot.

Like everybody else in the quarter, Ella believed the cholera was carried by foul nocturnal vapors arising from the surrounding swamp, so she and Thomas kept their shutters and doors closed tight against the night air, doing their best to protect their daughter from the killing disease that had already taken so many.

The rapping on the door became more insistent. Ella pushed against Thomas with her foot. On the second shove he awoke with a snort.

“Thomas! See to the door,” she whispered, “and mind Yewande.”

Wearing only a pair of cotton trousers, Thomas eased himself from the bed and crossed the room. He lifted the bar and pulled open the door, but his broad muscled back blocked the visitors’ faces. From the flickering glare cast around her husband, Ella could tell one of the callers held a lantern.

“Thomas,” came the familiar voice, “get Ella up.”

Ella started at the words. It was Sylvie, the master’s cook. The woman lived all the way up at the mansion and would have no good reason to be out this time of night unless it was something bad.

“Now?” Thomas whispered. “She’s sleeping.”

“She needs to carry her baby up to the master’s house,” Sylvie said. “Ella got to make haste on it. Mistress Amanda is waiting on her.”

“What she wanting with my woman and child in the dead of night?” Ella heard the alarm rising in her husband’s voice.

“Thomas, you know it ain’t neither night nor day for Mistress Amanda. She ain’t slept a wink since the funeral. And she’s grieving particular bad tonight. Her medicine don’t calm her down no more. She ain’t in no mood to be trifled with.”

“Old Silas,” Thomas pled to another unseen caller, “you tell the mistress that Ella will come by tomorrow, early in the morning.” Then he dropped his voice to a hush. “You know the mistress ain’t right in her head.”

Old Silas had more pull than anybody with the master, but from the lack of response, Ella imagined Silas’s gray head, weathered skin stretched tight over his skull, shaking solemnly.

Thomas let go a deep breath and then turned back to his wife. Behind him, Ella could hear the talk as it continued between the couple outside.

“You know good and well she didn’t say to fetch Ella,” Old Silas whispered harshly to his wife. “Just the baby, she said. What’s in your head?”

“Shush!” Aunt Sylvie fussed. “You didn’t see what I seen. I know what I’m doing.”

Ella met them at the door holding the swaddled infant. Not yet fourteen, Ella wore a ripped cotton shift cut low for nursing, and even in the heat of the cabin, she trembled. The yellow light lit the faces of the cook and her husband.

“What she want with Yewande?” Ella whimpered. “What she going to do to my baby?”

“Ella, she ain’t going to hurt your baby,” Sylvie assured. “Mistress wouldn’t do that for the world.”

“But why—”

Old Silas reached out and laid a gentle hand on Ella’s shoulder. “I expect she wants to name your girl, is all.” His voice was firm but comforting. He spoke more like the master than any slave. “That right, Sylvie?”

“Of course!” Sylvie said, as if hearing the explanation for the first time. “I expect that’s all it is. Mistress Amanda wants to name your girl.”

“But Master Ben names the children,” Ella argued.

“You heard what the master said,” Sylvie fussed. “Things got to change. We all got to mind her wishes until she comes through this thing. No use fighting it.”

Silas’s tone was kinder. “Mistress has taken an interest in your child from the start,” he explained. “Her Becky passed the very hour your girl was born. I suppose their souls might have touched, one coming and the other leaving. No doubt that’s why the mistress thinks your child so special. Every time the mistress hears your baby cry, she asks after Yewande’s health.”

Ella pulled the child closer to her breast and set her mouth to protest.

“Ella, don’t make a fuss,” Sylvie said impatiently. “Just do what she says tonight. Anything in the world to calm her down. Nobody getting any rest until she do. Let her name your baby if she has a mind. She been taking so much medicine, she’ll forget her own name by morning.”

Ella saw the resoluteness in the faces of the couple. She finally gave a trembling nod.

As the three walked down the lane of cabins, they passed smoldering heaps of pine and cypress, attempts by the inhabitants to purify the air and keep the mosquitoes at bay. The acrid, suffocating smoke seemed to travel with the little group, enveloping them in a cloud that seared the lungs. Up in the distance, the lights in the great house came into view. No words were spoken as Sylvie, ever crisp and efficient, walked beside Ella while Silas lit the path.

It was Old Silas whom the master had first sent down to the quarters days ago with the news of Miss Becky’s death. Ella remembered how odd Silas’s little speech had been.

“Miss Becky has passed of a summer fever,” he said, “not the cholera, understand? If any of those who come to pay respects should ask you, that is what you are to say. It was a summer fever that took Miss Becky. Don’t say a word more.”

Someone had asked Silas why they had to lie. It was known to everyone on the plantation that the girl had come down with the same sickness that had killed nearly two dozen of his field hands. Sylvie had already let it be known that she had watched Miss Becky suffering in her four-poster bed, halfway to heaven on her feather mattress. Sylvie had witnessed the sudden nausea and the involuntary discharges that didn’t let up through the entire night. She had seen the girl’s eyes, once the color of new violets, go dim and sink deep into their sockets, her face looking more like that of an ancient woman exhausted by life than a twelve-year-old girl. From what Sylvie had said, Miss Becky’s dying had been no different than their own children’s.

Before answering the question, Silas jawed the chaw of tobacco to his other cheek. “He’s doing it to protect Miss Becky’s good name. Master says the cholera is not a quality disease. The highborn don’t come down with such. Especially no innocent twelve-year-old white girl.” Silas put two fingers up to his mouth and let go a stream of brown juice.

A dark laughter rippled through the survivors who stood there, all of whom had lost family or friends. What Silas wouldn’t say, Sylvie made sure the others knew. She said the master was so afraid of what his neighbors thought he had refused to send to Delphi for the doctor lest the news get out that Miss Becky had caught a sickness so foul that it was reserved for Negroes and the Irish. He had stood there and watched while the girl’s breathing became so faint it didn’t even disturb the fine linen sheet that covered her. He ranted about how Rubina, Becky’s constant companion and the daughter of a house slave, was healthy as a colt. “There is no way,” he swore, “the cholera would pass over a slave and strike down a white girl!”

Sylvie remembered the mistress’s face when her husband has said that. The cook had never seen that much agony in a white person’s eyes.

When all hope was lost, the master finally turned his back on his wife and daughter and home, leaving Becky to lie motionless, shrouded by the embroidered canopy of pink-and-white roses; Mistress Amanda to witness alone the inevitable end; and little Rubina to sob outside her dying playmate’s room. He rounded up a work gang and several bottles of whiskey, saddled his horse, and hightailed it out to the swamps to burn more Delta acreage.

“I guess that’s the white man’s way,” Sylvie had told them all, disgusted. “Lose a child, sire more land.”

That’s when the mistress’s mind finally broke. At first she wanted to have little Rubina whipped and her wounds salted, sure the girl had given her daughter the disease. But soon enough she relented. It was clear that she couldn’t hurt Becky’s friend. Mistress Amanda’s crazed search for blame finally settled on her husband. She cursed him night and day and threw china dishes against the wall. When Master Ben sent for some medicine to calm her, she swallowed all she could get her hands on. Anyway, that’s what those who worked in the house said.

Sylvie reached her arm around the young mother’s shoulder. Ella felt sure it was as much to keep her from bolting as it was to comfort her. Not that Ella hadn’t thought about running off with her baby into the darkness and hiding in the swamps, waiting out the mistress’s memory. But nobody had ever survived for more than two days out in the swamps.

Even if she did make it past two days, it was no guarantee the mistress would come to her senses. Since the day of the funeral, the mistress’s silhouette could be seen through her bedroom window at all times of night, her arms animated, her fists shaking accusingly at nobody.

Ella didn’t know what happened first, Sylvie’s grip tightening to a bruising clench or the gunshot that seemed to crack right over her head. The small procession halted and they all gazed up at the house.

“Lord, what she done now?” Sylvie said.

While they watched, Master Ben came storming down the back steps from the upstairs gallery in his nightshirt and bare feet, dragging his bed linen behind him.

“It’s about time y’all got here. She’s about to hunt you down and she’s got her daddy’s derringer.”

The group stepped aside to let him pass. “My advice,” he grumbled without looking back, “is to hurry up before she reloads.”

“God be great,” Sylvie said under her breath. “I wish she would go ahead and shoot the man so we could all get some peace.”