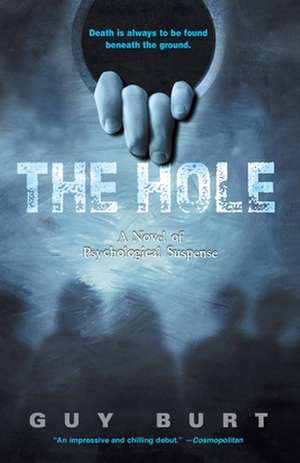

The Hole

Autor Guy Burten Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2002

–Publishers Weekly

On a spring day in England, six teenagers venture to a neglected part of their school where there is a door to a small windowless cellar. Behind the door, the old stairs have rotted away. A boy unfurls a rope ladder and five descend into The Hole. The sixth closes the door, locks it from the outside, and walks calmly away. The plan is simple: They will spend three days locked in The Hole and emerge to become part of the greatest prank the school has ever seen. But something goes terribly wrong. No one is coming back to let them out . . . ever.

Taut and eerie, suspenseful and disturbing, The Hole is a compelling novel of physical endurance, psychological survival, and unforgettable revelations made all the more stunning by its shocking end.

“A frighteningly good plot . . . Expertly borrows the horror and tension that made William Golding’s Lord of the Flies such a success.”

–Metronews

“COMPULSIVELY SINISTER.”

–The Times (London)

BB/Ballantine Books/ 44655 /$ in USA • $ in Canada

Visit our Web site at www.ballantinebooks.com

Preț: 86.21 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 129

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.50€ • 17.22$ • 13.65£

16.50€ • 17.22$ • 13.65£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345446558

ISBN-10: 0345446550

Pagini: 164

Dimensiuni: 213 x 140 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345446550

Pagini: 164

Dimensiuni: 213 x 140 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Guy Burt won the W. H. Smith Young Writers Award when he was twelve. He wrote The Hole, his first novel, when he was eighteen. He is also the author of Sophie and The Dandelion Clock. Burt attended Oxford University and taught for three years at Eton. He lives in Oxford.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

In the last Easter term, before the Hole, life was

bright and good at Our Glorious School. Charged

with the fresh self-confidence that steps in on

the brink of adulthood, we all knew our futures as

we walked out our lives under the arches and below

the walls.

The story begins, though, a little later than that; and

perhaps it is still not finished. At least, I have not yet

felt in me that the Hole is finished. But telling this story

will, I hope, move me a step further away from it, and maybe

help me to forget some of what happened.

It was a clear, unseasonably warm day when the six figures

made their way across the sun-washed flags of the quad to

the side of the English block. Down there, in the dark

hollow of a buttress, a rusted iron stairway circled its way

into the ground. One after another, they followed its spiral

and disappeared into the triangular shadow. A long time

passed, and the sun shifted in the sky and slipped its light

through different classroom windows, briefly illuminating

battered leather briefcases and untidy stacks of paper. The

accumulated and forgotten detritus of the spent term grew

warm for a while, and then a thin cloud began to draw over

from the east and the classrooms were dulled. A single

figure appeared at the head of the iron staircase and

paused, looking carefully around the deserted driveways and

empty cricket pitches. With hands hooked into the pockets of

his clean gray trousers, he set off towards the woods that

flanked the pavilion, fair hair flapping gently in the

growing breeze.

And although it was not yet apparent, this figure--dwindling

towards the late spring green of the woods--was now, from

one viewpoint, a murderer.

"It's not even as though anyone would mind," Alex said, and

went off to the small lavatory set back around the corner,

tak-ing her large and shabby knapsack with her. There was

another small room there, which had most likely served once

as a storage closet. Mike couldn't guess when this place had

last been used for anything. The smell of it was dry and

cool. There was dust between the stones of the floor that

had set, become fossilized.

Mike doubled his sleeping bag up behind his back as a sort

of cushion. The Hole was blank and harsh in the naked light of the bulb,

like a badly adjusted TV picture. Frankie was searching through her

bags for something, pulling out articles of clothing and other junk,

stuffing them back in again, working seemingly at random. There was a

faint, glassy sound of water into water, and then the hiss and roar of the huge gray cistern. Frankie triumphantly flourished an octagonal cardboard box.

"Anyone want some?" she asked happily. The others looked at her.

"What is it?" Geoff asked suspiciously.

"Turkish delight," returned Frankie. "Lovely. I got two

boxes, just in case."

"No thanks," Mike said. He wondered idly what the second box might be in case of.

"Me neither, if it's all the same to you," Geoff said. "That stuff--it tastes like . . . I don't know, it tastes . . ."

"It's rose-flavored," Frankie said.

"No, it tastes like . . ."

Alex returned, shaking her hands violently at the wrists.

"Ah, for heaven's sake!" shouted Frankie, and a small plume of white sugar powder leapt up from the box she was holding. "You got water all over me."

"Did anyone think to bring a towel?" Alex asked. Mike shook his head. It

hadn't crossed his mind.

"I have," said Liz. That followed, Mike decided. You'd never expect someone like Frankie to remember towels, but Liz would. He wasn't sure why he had this impression of her; it just seemed natural.

"Thanks," said Alex. "That water's too cold for me."

"What time is it now?" asked Frankie.

"Nine. Why do you need to know?" Geoff said. "You keep on asking me what bloody time it is."

"I'm tired. And I forgot my watch," Frankie said.

"How can you be tired?" Alex asked. "All we've done since four o'clock is sit around chatting."

"I haven't," Mike said. "I joined a rather fascinating little trip to

see some rock formations and then hiked across the moors for an hour or

two." They laughed.

"That's exactly the sort of thing Morris and friends would get up to," Geoff said.

"Thank God we didn't go," Alex said, with a shiver. "Last field trip was a nightmare. I spent the whole week soaking wet and half-blinded by rain." She pushed her hair back from her face and continued. "And I hate mountains. I'm not a mountain person. More a living-room person, I think."

"You can thank Martyn for it all," Frankie said.

"Yeah," Mike said. "Out of the field trip and into the Hole, to coin a phrase."

"I quite like it down here," Alex said. "I know it's not exactly comfortable--or big, for that matter--but you get the impression that, with a little care, it could be almost cozy. Some curtains, and tasteful rugs. You know."

"Funny," Frankie said. "Very funny. Ha ha."

By now, Mike thought, the field trip probably would have

been across a mountain or two. He'd been on the previous expeditions,

and had really rather enjoyed himself. But, of course, the chance to

become involved with one of Martyn's schemes was worth any sacrifice.

Which was why, he reflected wryly, he was stuck in a cellar under the

English block instead of above the snowline in the Peak District. Around

him the others had arranged their possessions on the floor of the

cellar. Geoff, lounging on one elbow next to him, waved a hand vaguely

over his knapsack and the untidy pile of clothing and tins of food that

was spread next to it.

"What I still don't get is how this place could just be here, but never

be used," he said. "It would make a great common room, or music room, or

something."

"Half Our Glorious School isn't used," Frankie said

dismissively. "My dad says the whole place needs a bloody good change

of management."

"Then your dad has the full support of the entire

student body," Geoff said.

"Frankie's right," Alex said. "There are

places like this all over the school. That bit behind the physics

department, for example. What's it used for? Nobody ever goes in

there."

"That's the butterfly collection," Liz said unexpectedly. Mike

always felt a lift of mild surprise when Liz spoke. "They only open it

every five years or so."

"You're joking," Geoff said, staring at her. "Butterflies?"

"Typical," said Frankie with a snort. "Betcha it's some

bequest or other. People are always bequesting things to us."

"Bequeathing," Mike said.

"Whatever." "I hereby bequeath to Our Glorious

School my entire collection of compromising photographs of the teaching

staff, to be left on permanent display in the dining rooms," Mike said.

"I'm hungry," Alex said. She took off her round wire-rimmed glasses and

started to polish them with a hanky. "How about a nearly bedtime snack?"

"Let's see what we have," Frankie said at once. Mike grinned. "Calm

down, ladies," he said. "One at a time."

"Condescending bastard," Frankie said. "This says French toast. I think I'll eat that."

"French toast?" Geoff said. "Sounds rather rude. 'Ello, darlin', how

about some French toast, then?"

Mike shuffled lower on his sleeping bag and closed his eyes against the hard light of the bulb. "I thought French toast was when you stuck your tongue out and licked the butter off," he said. Alex snorted with laughter, and then stopped herself rather guiltily.

"Disgusting, Mikey," Frankie said.

"Not as disgusting as that Turkish stuff," Geoff said. "It tastes so bloody pink, that's all."

This is how it all began. But remember, we were very young then.

I can hear Martyn saying to us, before we went down there, "This is an

experiment with real life." That was what he called it.

"Isn't that a bit ambitious?" I asked, and he smiled.

Martyn's smile was wide and easy, and it sat happily in Martyn's round fair face. Teachers knew what Martyn was. He was a thoughtful, rather slow boy who could be trusted with responsibility. He was always friendly, always willing to

chat with old Mr. Stevens about fishing or stop by to take a look at Dr.

James's garden. He was a good boy; sensible. Stanford once said, "That

boy is a damned fine head of library," which I think probably surprised

the staff as much as the pupils--Stanford not being known for tender

words about anyone.

We also knew who Martyn was, and revelled in the complete and wonderful illusion he had created. Because we knew that it

was Martyn who was behind the Gibbon incident; Martyn who orchestrated

the collapse of the End of Term Address; Martyn who was perhaps the

greatest rebel Our Glorious School had ever seen. The duplicity of Martyn's life was, in our eyes,

something admirable and enviable. Perhaps if we had taken the time to

examine this, we might have been closer to guessing what was later to

happen. But it never occurred to us that the deception might involve

more than the two layers we saw.

Strange how time changes things around us.

Strange how we change with time.

Sadly, schools deal in the sale and exchange of knowledge, not wisdom. And it was wisdom that we could have used back then, all that time ago. And we were not equipped. We were not ready.

"Isn't that a bit ambitious?" I said, and the voice was a child's

voice, trusting and entirely innocent. And the voice that answered it

was old; far too old for the round, smiling face and pale blue eyes.

"Oh, I don't think so," Martyn said to me.

From the Hardcover edition.

bright and good at Our Glorious School. Charged

with the fresh self-confidence that steps in on

the brink of adulthood, we all knew our futures as

we walked out our lives under the arches and below

the walls.

The story begins, though, a little later than that; and

perhaps it is still not finished. At least, I have not yet

felt in me that the Hole is finished. But telling this story

will, I hope, move me a step further away from it, and maybe

help me to forget some of what happened.

It was a clear, unseasonably warm day when the six figures

made their way across the sun-washed flags of the quad to

the side of the English block. Down there, in the dark

hollow of a buttress, a rusted iron stairway circled its way

into the ground. One after another, they followed its spiral

and disappeared into the triangular shadow. A long time

passed, and the sun shifted in the sky and slipped its light

through different classroom windows, briefly illuminating

battered leather briefcases and untidy stacks of paper. The

accumulated and forgotten detritus of the spent term grew

warm for a while, and then a thin cloud began to draw over

from the east and the classrooms were dulled. A single

figure appeared at the head of the iron staircase and

paused, looking carefully around the deserted driveways and

empty cricket pitches. With hands hooked into the pockets of

his clean gray trousers, he set off towards the woods that

flanked the pavilion, fair hair flapping gently in the

growing breeze.

And although it was not yet apparent, this figure--dwindling

towards the late spring green of the woods--was now, from

one viewpoint, a murderer.

"It's not even as though anyone would mind," Alex said, and

went off to the small lavatory set back around the corner,

tak-ing her large and shabby knapsack with her. There was

another small room there, which had most likely served once

as a storage closet. Mike couldn't guess when this place had

last been used for anything. The smell of it was dry and

cool. There was dust between the stones of the floor that

had set, become fossilized.

Mike doubled his sleeping bag up behind his back as a sort

of cushion. The Hole was blank and harsh in the naked light of the bulb,

like a badly adjusted TV picture. Frankie was searching through her

bags for something, pulling out articles of clothing and other junk,

stuffing them back in again, working seemingly at random. There was a

faint, glassy sound of water into water, and then the hiss and roar of the huge gray cistern. Frankie triumphantly flourished an octagonal cardboard box.

"Anyone want some?" she asked happily. The others looked at her.

"What is it?" Geoff asked suspiciously.

"Turkish delight," returned Frankie. "Lovely. I got two

boxes, just in case."

"No thanks," Mike said. He wondered idly what the second box might be in case of.

"Me neither, if it's all the same to you," Geoff said. "That stuff--it tastes like . . . I don't know, it tastes . . ."

"It's rose-flavored," Frankie said.

"No, it tastes like . . ."

Alex returned, shaking her hands violently at the wrists.

"Ah, for heaven's sake!" shouted Frankie, and a small plume of white sugar powder leapt up from the box she was holding. "You got water all over me."

"Did anyone think to bring a towel?" Alex asked. Mike shook his head. It

hadn't crossed his mind.

"I have," said Liz. That followed, Mike decided. You'd never expect someone like Frankie to remember towels, but Liz would. He wasn't sure why he had this impression of her; it just seemed natural.

"Thanks," said Alex. "That water's too cold for me."

"What time is it now?" asked Frankie.

"Nine. Why do you need to know?" Geoff said. "You keep on asking me what bloody time it is."

"I'm tired. And I forgot my watch," Frankie said.

"How can you be tired?" Alex asked. "All we've done since four o'clock is sit around chatting."

"I haven't," Mike said. "I joined a rather fascinating little trip to

see some rock formations and then hiked across the moors for an hour or

two." They laughed.

"That's exactly the sort of thing Morris and friends would get up to," Geoff said.

"Thank God we didn't go," Alex said, with a shiver. "Last field trip was a nightmare. I spent the whole week soaking wet and half-blinded by rain." She pushed her hair back from her face and continued. "And I hate mountains. I'm not a mountain person. More a living-room person, I think."

"You can thank Martyn for it all," Frankie said.

"Yeah," Mike said. "Out of the field trip and into the Hole, to coin a phrase."

"I quite like it down here," Alex said. "I know it's not exactly comfortable--or big, for that matter--but you get the impression that, with a little care, it could be almost cozy. Some curtains, and tasteful rugs. You know."

"Funny," Frankie said. "Very funny. Ha ha."

By now, Mike thought, the field trip probably would have

been across a mountain or two. He'd been on the previous expeditions,

and had really rather enjoyed himself. But, of course, the chance to

become involved with one of Martyn's schemes was worth any sacrifice.

Which was why, he reflected wryly, he was stuck in a cellar under the

English block instead of above the snowline in the Peak District. Around

him the others had arranged their possessions on the floor of the

cellar. Geoff, lounging on one elbow next to him, waved a hand vaguely

over his knapsack and the untidy pile of clothing and tins of food that

was spread next to it.

"What I still don't get is how this place could just be here, but never

be used," he said. "It would make a great common room, or music room, or

something."

"Half Our Glorious School isn't used," Frankie said

dismissively. "My dad says the whole place needs a bloody good change

of management."

"Then your dad has the full support of the entire

student body," Geoff said.

"Frankie's right," Alex said. "There are

places like this all over the school. That bit behind the physics

department, for example. What's it used for? Nobody ever goes in

there."

"That's the butterfly collection," Liz said unexpectedly. Mike

always felt a lift of mild surprise when Liz spoke. "They only open it

every five years or so."

"You're joking," Geoff said, staring at her. "Butterflies?"

"Typical," said Frankie with a snort. "Betcha it's some

bequest or other. People are always bequesting things to us."

"Bequeathing," Mike said.

"Whatever." "I hereby bequeath to Our Glorious

School my entire collection of compromising photographs of the teaching

staff, to be left on permanent display in the dining rooms," Mike said.

"I'm hungry," Alex said. She took off her round wire-rimmed glasses and

started to polish them with a hanky. "How about a nearly bedtime snack?"

"Let's see what we have," Frankie said at once. Mike grinned. "Calm

down, ladies," he said. "One at a time."

"Condescending bastard," Frankie said. "This says French toast. I think I'll eat that."

"French toast?" Geoff said. "Sounds rather rude. 'Ello, darlin', how

about some French toast, then?"

Mike shuffled lower on his sleeping bag and closed his eyes against the hard light of the bulb. "I thought French toast was when you stuck your tongue out and licked the butter off," he said. Alex snorted with laughter, and then stopped herself rather guiltily.

"Disgusting, Mikey," Frankie said.

"Not as disgusting as that Turkish stuff," Geoff said. "It tastes so bloody pink, that's all."

This is how it all began. But remember, we were very young then.

I can hear Martyn saying to us, before we went down there, "This is an

experiment with real life." That was what he called it.

"Isn't that a bit ambitious?" I asked, and he smiled.

Martyn's smile was wide and easy, and it sat happily in Martyn's round fair face. Teachers knew what Martyn was. He was a thoughtful, rather slow boy who could be trusted with responsibility. He was always friendly, always willing to

chat with old Mr. Stevens about fishing or stop by to take a look at Dr.

James's garden. He was a good boy; sensible. Stanford once said, "That

boy is a damned fine head of library," which I think probably surprised

the staff as much as the pupils--Stanford not being known for tender

words about anyone.

We also knew who Martyn was, and revelled in the complete and wonderful illusion he had created. Because we knew that it

was Martyn who was behind the Gibbon incident; Martyn who orchestrated

the collapse of the End of Term Address; Martyn who was perhaps the

greatest rebel Our Glorious School had ever seen. The duplicity of Martyn's life was, in our eyes,

something admirable and enviable. Perhaps if we had taken the time to

examine this, we might have been closer to guessing what was later to

happen. But it never occurred to us that the deception might involve

more than the two layers we saw.

Strange how time changes things around us.

Strange how we change with time.

Sadly, schools deal in the sale and exchange of knowledge, not wisdom. And it was wisdom that we could have used back then, all that time ago. And we were not equipped. We were not ready.

"Isn't that a bit ambitious?" I said, and the voice was a child's

voice, trusting and entirely innocent. And the voice that answered it

was old; far too old for the round, smiling face and pale blue eyes.

"Oh, I don't think so," Martyn said to me.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“An impressive and chilling debut.”

–Cosmopolitan

“[A] COMPELLING PSYCHOLOGICAL TALE . . . A QUICK AND INTRIGUING BOOK WITH A TRULY SATISFYING ENDING.”

–Publishers Weekly

“A frighteningly good plot . . . Expertly borrows the horror and tension that made William Golding’s Lord of the Flies such a success.”

–Metronews

“COMPULSIVELY SINISTER.”

–The Times (London)

–Cosmopolitan

“[A] COMPELLING PSYCHOLOGICAL TALE . . . A QUICK AND INTRIGUING BOOK WITH A TRULY SATISFYING ENDING.”

–Publishers Weekly

“A frighteningly good plot . . . Expertly borrows the horror and tension that made William Golding’s Lord of the Flies such a success.”

–Metronews

“COMPULSIVELY SINISTER.”

–The Times (London)