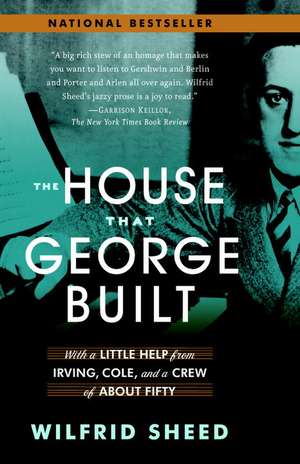

The House That George Built: With a Little Help from Irving, Cole, and a Crew of about Fifty

Autor Wilfrid Sheeden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2008

It began when immigrants in New York’s Lower East Side heard black jazz and blues–and it surged into an artistic torrent nothing short of miraculous. Broke but eager, Izzy Baline transformed himself into Irving Berlin, married an heiress, and embarked on a string of hits from “Always” to “Cheek to Cheek.” Berlin’s spiritual godson George Gershwin, in his brief but incandescent career, straddled Tin Pan Alley and Carnegie Hall, charming everyone in his orbit. Possessed of a world-class ego, Gershwin was also generous, exciting, and utterly original. Half a century later, Gershwin love songs like “Someone to Watch Over Me,” “The Man I Love,” and “Love Is Here to Stay” are as tender and moving as ever.

Sheed also illuminates the unique gifts of the great jazz songsters Hoagy Carmichael and Duke Ellington, conjuring up the circumstances of their creativity and bringing back the thrill of what it was like to hear “Georgia on My Mind” or “Mood Indigo” for the first time. The Golden Age of song sparked creative breakthroughs in both Broadway musicals and splashy Hollywood extravaganzas. Sheed vividly recounts how Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers, Jerome Kern, and Johnny Mercer spread the melodic wealth to stage and screen.

Popular music was, writes Sheed, “far and away our greatest contribution to the world’s art supply in the so-called American Century.” Sheed hung out with some of the great artists while they were still writing–and better than anyone, he knows great music, its shimmer, bite, and exuberance. Sparkling with wit, insight, and the grace notes of wonderful songs, The House That George Built is a heartfelt, intensely personal portrait of an unforgettable era.

A delightfully charming, funny, and most illuminating portrait of songwriters and the Golden Age of American Popular Song. Mr. Sheed’s carefully chosen depictions and anecdotes recapture that amazingly creative period, a moment in time in which I was so fortunate to be surrounded by all that magic.”

–Margaret Whiting

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 113.97 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.81€ • 22.83$ • 18.04£

21.81€ • 22.83$ • 18.04£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812970180

ISBN-10: 0812970187

Pagini: 335

Ilustrații: CHAPTER-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812970187

Pagini: 335

Ilustrații: CHAPTER-OPENING PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Wilfred Sheed is the author of six novels, two of which, Office Politics and People Will Always Be Kind, were nominated for National Book Awards. He has written three collections of criticism, one of which was nominated by the National Book Critics Circle. Among his other books is a notable memoir of Clare Boothe Luce, who told him that Irving Berlin was the vainest man she ever met and George Gershwin one of the most basically modest. He lives with his wife, Miriam Ungerer, in North Haven, New York

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

The Road to Berlin

There are several ways of defining and measuring an era, but an excellent place to start is by checking out the media of the day and what they could or could not do at the moment. For example, when sound recording first came along, the singers belted into it as if performing to an empty stadium. The name that springs to mind is Caruso, the world’s biggest voice. But with the coming of microphones in the 1920s, singing became more personal, and the name became Bing Crosby, the world’s friendliest voice. So songs became brisker and less operatic, to suit not only the mike but the piano rack and the record cabinet. In short, the familiar thirty-two-bar song, which now seems to have been fixed in the stars, was actually fixed by the practicalities of sheet-music publishing and confirmed by the limitations of ten-inch records.

Or one might define an era in terms of women’s fashions and the consequent rise of impulse dancing on improvised dance floors. You can’t really jitterbug in a hoopskirt or bustle. Swing follows costume, and the big news was that by the 1910s skirts had become just loose enough and short enough to liberate the wearer from the tyranny of twirling through eternal waltzes in ballrooms as big as basketball courts, and freed her to do fox-trots and anything else that could be done in short, quick steps on, if necessary, living room floors with rugs rolled up. So that’s what the boys wrote for next. By the 1920s, the whole lower leg could swing out in Charlestons and other abandoned exercises. Songwriters celebrated that with a decade of fast-rhythm numbers. This has always been a dancing country, and never more so than in the Depression, when people trucked their blues away in marathons, or in seedy dance halls. “Ten Cents a Dance” was better than no income at all. And the Lindy Hop was as good as a gym class too.

And so on, through the arrival of women’s slacks in the late 1930s and their increased popularity in World War II for both work and play— Rosie the Riveter could jitterbug on her lunch break without leaving the floor. All she needed was a beat. Which brings us with a final bump and a grinding halt to rock and roll and the totally free-form dancing of today, which can be done with no clothes at all to a beat in your own head while you’re watching something else on television.

The huge, nonnegotiable gap between then and now is that in the past, music and dancing had always been disciplined by something or other. There had always been rules for doing it right, and even the wildest flights of swing and swing dancing had rested on a bed of piano lessons and dance lessons, and dress codes as well. Cab Calloway in a zoot suit was still a dressy man, a dandy; Cab Calloway in jeans or shorts over his knees would not have been dressed at all in the old sense. Going out dancing used to be an event, like going to church. Today all that remains are the rituals of prom night, which must seem weirder every year.

The era might also be measured in demographics or political cycles or even weather patterns. But the brilliant strand of music that, running through Irving Berlin and George Gershwin, has become the music of the standards began with a bang—with pianos being hoisted into tenements, a magnificent and noisy event, and it ended with guitars being schlepped quietly, almost parenthetically, into ranch houses and split-levels to herald the arrival of the great non-event that has been with us ever since.

But first the bang, then the whimper. There was no way of receiving such an impressive object as a piano quietly in such close quarters. Whether it bounced up the staircase or jangled its way over the fire escape and in through the window, the neighbors knew about it all right, and would be reminded again every time Junior hit the keys and shook the building. Short of a Rolls-Royce or carriage and horses, there was never such a status symbol, with the consequence that although “all the families around us were poor,” said Harry Ruby, “they all had pianos.” For such important matters, time-payments were born.

So the parents went into hock and found room for the damn thing someplace, and artistic Darwinism did the rest. You buy a piano for Ira Gershwin, and George is the one who plays it, although sometimes you had to live through a week of hell to learn this. As anyone knows who has ever housed a child and a piano, every tot who walks through the door will bang the bejesus out of the new toy for a few minutes, get bored, and come back, and back again, and bang some more, but then successively less and less until the dust starts to move in and claim it. . . . Unless the child finds something interesting in the magic box, a familiar tune that stammers to life under his fingers, or a promising and unfamiliar one; a chord that sounds good, and rolls out into a respectable arpeggio as well, with, saints be praised, a bass line that actually works for a bar or two—after which a gifted kid with an instrument is like a teenager with his first car and a tank full of gas. Where to, James: Charleston, Chattanooga, or Kalamazoo? Two-steps, or concertos, or parts unknown?

“Well, he’ll probably settle down eventually,” hoped the parents who had only bought the thing for the sake of respectability and maybe for some civilized graces around here. It speaks wonders for those parents in that era that they knew that being a famous lawyer or doctor wasn’t enough in life. If you weren’t a person of cultivation, you were still a bum.

But some of the kids insisted on being bums anyway, and sometimes the piano only made them worse. There were low-life uses for the instrument as well as high, and all the classical music lessons the parents could shout for weren’t always enough to keep Junior out of the gutter, especially once ragtime had come along, in Frank Loesser’s phrase, “to fill the gutters in gold.” Talk about subversive —not even Elvis Presley rolling his hips had as many parents and preachers up and howling and sending for the exorcism unit as ragtime did. After all, not too many kids have hips like Elvis’s, but anyone who could play “Chopsticks” or whistle “The Star-Spangled Banner” could syncopate, and in no time, as Irving Berlin bragged in two of his hits, “Everybody’s doing it” in one form or another, from “Italian opera singers” learning to snap their fingers, to “dukes and lords and Russian czars,” who settled for throwing their shoulders in the air and no doubt rolling their eyes. And there was no place to hide from it, even in an ivory tower. In fact, it would become a staple of B-movie musicals to show a professor at first frowning mightily as he hears the kids jazzing up a well-known classic, only to furtively wind up, beneath the gown or the desk, tapping his own foot too, as if the body snatchers had seized that much of him. And if the “professoriate” and the “long hairiate” couldn’t stand up to it, the kid at the keyboard wasn’t even going to try. Because this is where ragtime belonged, its birthplace, its office and its home, and the great Scott Joplin was still making tunes out of it, which maybe they could use in place of Czerny’s finger exercises while no one was listening.

“What’s that you’re playing? That’s not what you’re supposed to be playing.” Someone was always listening, and one imagines a thousand fights a day over this as George or Harold or Fats would stray once more from his scales and his Bach-made-easy and start to vamp the music of his pulse, the music of the streets.

Well, just because everybody was doing it didn’t make it right. But remember: There was no other living music around except the music of the streets; there were no radios or records, or even talking pictures. Unless your parents took you to the theater, like Jerome Kern’s, or to concerts, like no one I can think of, “good” music only existed in the form of hieroglyphs on a page, which meant that in effect it was a dead language, and a growing child could not survive on dead languages alone. So they listened instead to the sounds that seeped out of the vaudeville house rear windows and under the doors of taverns, and to the riffs of the barrel organs and ice cream trucks playing “Nola” and “The Whistler and His Dog,” and from the upstairs windows of the tenements themselves, where seditious neighbors had actually acquired the latest sheet music and couldn’t wait to bang it out on their new pianos, for the rest of the community to swing to and curse.

But perhaps the most effective medium for spreading the new music around were the average absentminded whistlers and hummers whose names were legion in those days, and still semi-legion when I was growing up in the 1940s and ’50s. In fact, I have a vague feeling I was one myself. Anyway, you had little choice about it. If you knew the music, you whistled it, as if all the backed-up melody in your head was forcing its way out through your mouth like steam from a kettle. And this medium was no respecter of class or location either. As late as the 1950s, you could still hear respectable bankers and businessmen in stark colors and homburg hats whistling their way to work like newsboys or Walt Disney’s dwarves. The very last time I heard a recognizable tune being whistled all the way through, it turned out to be coming from a natty distinguished senior in the next booth of a men’s room who was whistling while he whatever. By that point in time, this man’s whistling had become the only sound in a quiet building, like a trumpet blowing “Taps” over an empty battlefield, but imagine how that whistle sounded for the first time, back in the days when the natty old man was still a scruffy old boy adding his two cents’ worth to the noise of the whistling businessmen and the cheerful whine of the calliopes and the soughs of violins being scraped on street corners.

And then imagine how it all sounded to that other small boy trying to get serious at the piano, but tempted like sin by the sounds of freedom outside, all of which, from the barrel organ to the guy on the corner trying to make a buck from his fiddle or harmonica, was at that moment syncopated. And it all went into Junior’s ears and hands and came out again, jumbled perhaps with Mr. Mozart’s music or whoever was on the rack that day for him to torture, and maybe with some verbal help from the wise guy next door, the result might be a song that someday might sell like hotcakes and cross the ocean too, until the whole world was playing and whistling it and some of the bums whose parents had despaired of them became very rich indeed, and the parents frowned and learned to tap their feet too, and moved uptown, where, thanks to their one very shrewd investment in a musical black box, they’d never have to work again. The piano lessons might have been wasted, but the hooky lessons were pure gold.

Or were the piano lessons really wasted? One of the proudest claims made for the American standards is that they were good music written by real musicians, however they got there, whether by studying at the best schools, like Kern and Rodgers, or by just listening, like Irving Berlin. Berlin never did learn the piano, but could spot a wrong note on the next block.

The school of “just listening” received an endorsement from the arrival of jazz in those years. The best jazz musicians created intricate harmonies without benefit of pencil or paper—disciplines that could take years to master at school. Classical lessons were still useful because they taught good from bad and what was good about good.

But playing hooky was vital—not just at the piano, playing Chopin and Brahms in ragtime, but playing hooky from the piano, just walking around and listening to the music of the city itself, which was experiencing a creative transformation right under these players’ ears.

The same wave of good luck that had brought so many eastern European Jews to New York had also brought enough Southern blacks to mount a Harlem renaissance, and just like that, two of the principal ingredients had arrived. The standards have actually been referred to as a Jewish response to black music, but this definition is a loaded compliment that neither party has rushed to claim. With such praise, Jews never know whether to take a bow or duck. In a safe house like this book, it is the highest compliment I can think of. But in the mouth of a WASP supremacist like Henry Ford, “Jewish” meant un- American and subversive, so don’t wave that compliment around or it might explode; and for blacks it just meant more of the minstrel-show syndrome. There go those darkies, making music again, haven’t they got a great sense of rhythm? As outsiders, both Jews and blacks had been positively expected to entertain, but when they did so, it automatically became a second-class thing to do. Show biz in general was the ultimate club that accepted Groucho Marx and invited his scorn.

Music is not produced by whole groups, but by one genius at a time, and it may be significant that the two families that gave us Irving Berlin and George Gershwin both fled Russia on the same great wave of czarist pogroms, only to find American black people not only singing about a similar experience, but using the Hebrew Bible as their text.

Blacks, too, had been to heaven and back. They had found the promised land in the form of emancipation, and for a few giddy years the taste of freedom had been all the milk and honey they needed. But when they (and the white man) woke up, they realized nothing much had changed. The slaves had been moved to another part of the ledger. They would still be working for the boss, the pharaoh, but they would have to look for their own food and lodging now and pay for it out of their still-empty pockets. And somehow the boss seemed to have multiplied to include any white man who wanted a shoe shine or simply a glass of water. Just say the word “boy” to any African American, even today, and he’ll remember.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Road to Berlin

There are several ways of defining and measuring an era, but an excellent place to start is by checking out the media of the day and what they could or could not do at the moment. For example, when sound recording first came along, the singers belted into it as if performing to an empty stadium. The name that springs to mind is Caruso, the world’s biggest voice. But with the coming of microphones in the 1920s, singing became more personal, and the name became Bing Crosby, the world’s friendliest voice. So songs became brisker and less operatic, to suit not only the mike but the piano rack and the record cabinet. In short, the familiar thirty-two-bar song, which now seems to have been fixed in the stars, was actually fixed by the practicalities of sheet-music publishing and confirmed by the limitations of ten-inch records.

Or one might define an era in terms of women’s fashions and the consequent rise of impulse dancing on improvised dance floors. You can’t really jitterbug in a hoopskirt or bustle. Swing follows costume, and the big news was that by the 1910s skirts had become just loose enough and short enough to liberate the wearer from the tyranny of twirling through eternal waltzes in ballrooms as big as basketball courts, and freed her to do fox-trots and anything else that could be done in short, quick steps on, if necessary, living room floors with rugs rolled up. So that’s what the boys wrote for next. By the 1920s, the whole lower leg could swing out in Charlestons and other abandoned exercises. Songwriters celebrated that with a decade of fast-rhythm numbers. This has always been a dancing country, and never more so than in the Depression, when people trucked their blues away in marathons, or in seedy dance halls. “Ten Cents a Dance” was better than no income at all. And the Lindy Hop was as good as a gym class too.

And so on, through the arrival of women’s slacks in the late 1930s and their increased popularity in World War II for both work and play— Rosie the Riveter could jitterbug on her lunch break without leaving the floor. All she needed was a beat. Which brings us with a final bump and a grinding halt to rock and roll and the totally free-form dancing of today, which can be done with no clothes at all to a beat in your own head while you’re watching something else on television.

The huge, nonnegotiable gap between then and now is that in the past, music and dancing had always been disciplined by something or other. There had always been rules for doing it right, and even the wildest flights of swing and swing dancing had rested on a bed of piano lessons and dance lessons, and dress codes as well. Cab Calloway in a zoot suit was still a dressy man, a dandy; Cab Calloway in jeans or shorts over his knees would not have been dressed at all in the old sense. Going out dancing used to be an event, like going to church. Today all that remains are the rituals of prom night, which must seem weirder every year.

The era might also be measured in demographics or political cycles or even weather patterns. But the brilliant strand of music that, running through Irving Berlin and George Gershwin, has become the music of the standards began with a bang—with pianos being hoisted into tenements, a magnificent and noisy event, and it ended with guitars being schlepped quietly, almost parenthetically, into ranch houses and split-levels to herald the arrival of the great non-event that has been with us ever since.

But first the bang, then the whimper. There was no way of receiving such an impressive object as a piano quietly in such close quarters. Whether it bounced up the staircase or jangled its way over the fire escape and in through the window, the neighbors knew about it all right, and would be reminded again every time Junior hit the keys and shook the building. Short of a Rolls-Royce or carriage and horses, there was never such a status symbol, with the consequence that although “all the families around us were poor,” said Harry Ruby, “they all had pianos.” For such important matters, time-payments were born.

So the parents went into hock and found room for the damn thing someplace, and artistic Darwinism did the rest. You buy a piano for Ira Gershwin, and George is the one who plays it, although sometimes you had to live through a week of hell to learn this. As anyone knows who has ever housed a child and a piano, every tot who walks through the door will bang the bejesus out of the new toy for a few minutes, get bored, and come back, and back again, and bang some more, but then successively less and less until the dust starts to move in and claim it. . . . Unless the child finds something interesting in the magic box, a familiar tune that stammers to life under his fingers, or a promising and unfamiliar one; a chord that sounds good, and rolls out into a respectable arpeggio as well, with, saints be praised, a bass line that actually works for a bar or two—after which a gifted kid with an instrument is like a teenager with his first car and a tank full of gas. Where to, James: Charleston, Chattanooga, or Kalamazoo? Two-steps, or concertos, or parts unknown?

“Well, he’ll probably settle down eventually,” hoped the parents who had only bought the thing for the sake of respectability and maybe for some civilized graces around here. It speaks wonders for those parents in that era that they knew that being a famous lawyer or doctor wasn’t enough in life. If you weren’t a person of cultivation, you were still a bum.

But some of the kids insisted on being bums anyway, and sometimes the piano only made them worse. There were low-life uses for the instrument as well as high, and all the classical music lessons the parents could shout for weren’t always enough to keep Junior out of the gutter, especially once ragtime had come along, in Frank Loesser’s phrase, “to fill the gutters in gold.” Talk about subversive —not even Elvis Presley rolling his hips had as many parents and preachers up and howling and sending for the exorcism unit as ragtime did. After all, not too many kids have hips like Elvis’s, but anyone who could play “Chopsticks” or whistle “The Star-Spangled Banner” could syncopate, and in no time, as Irving Berlin bragged in two of his hits, “Everybody’s doing it” in one form or another, from “Italian opera singers” learning to snap their fingers, to “dukes and lords and Russian czars,” who settled for throwing their shoulders in the air and no doubt rolling their eyes. And there was no place to hide from it, even in an ivory tower. In fact, it would become a staple of B-movie musicals to show a professor at first frowning mightily as he hears the kids jazzing up a well-known classic, only to furtively wind up, beneath the gown or the desk, tapping his own foot too, as if the body snatchers had seized that much of him. And if the “professoriate” and the “long hairiate” couldn’t stand up to it, the kid at the keyboard wasn’t even going to try. Because this is where ragtime belonged, its birthplace, its office and its home, and the great Scott Joplin was still making tunes out of it, which maybe they could use in place of Czerny’s finger exercises while no one was listening.

“What’s that you’re playing? That’s not what you’re supposed to be playing.” Someone was always listening, and one imagines a thousand fights a day over this as George or Harold or Fats would stray once more from his scales and his Bach-made-easy and start to vamp the music of his pulse, the music of the streets.

Well, just because everybody was doing it didn’t make it right. But remember: There was no other living music around except the music of the streets; there were no radios or records, or even talking pictures. Unless your parents took you to the theater, like Jerome Kern’s, or to concerts, like no one I can think of, “good” music only existed in the form of hieroglyphs on a page, which meant that in effect it was a dead language, and a growing child could not survive on dead languages alone. So they listened instead to the sounds that seeped out of the vaudeville house rear windows and under the doors of taverns, and to the riffs of the barrel organs and ice cream trucks playing “Nola” and “The Whistler and His Dog,” and from the upstairs windows of the tenements themselves, where seditious neighbors had actually acquired the latest sheet music and couldn’t wait to bang it out on their new pianos, for the rest of the community to swing to and curse.

But perhaps the most effective medium for spreading the new music around were the average absentminded whistlers and hummers whose names were legion in those days, and still semi-legion when I was growing up in the 1940s and ’50s. In fact, I have a vague feeling I was one myself. Anyway, you had little choice about it. If you knew the music, you whistled it, as if all the backed-up melody in your head was forcing its way out through your mouth like steam from a kettle. And this medium was no respecter of class or location either. As late as the 1950s, you could still hear respectable bankers and businessmen in stark colors and homburg hats whistling their way to work like newsboys or Walt Disney’s dwarves. The very last time I heard a recognizable tune being whistled all the way through, it turned out to be coming from a natty distinguished senior in the next booth of a men’s room who was whistling while he whatever. By that point in time, this man’s whistling had become the only sound in a quiet building, like a trumpet blowing “Taps” over an empty battlefield, but imagine how that whistle sounded for the first time, back in the days when the natty old man was still a scruffy old boy adding his two cents’ worth to the noise of the whistling businessmen and the cheerful whine of the calliopes and the soughs of violins being scraped on street corners.

And then imagine how it all sounded to that other small boy trying to get serious at the piano, but tempted like sin by the sounds of freedom outside, all of which, from the barrel organ to the guy on the corner trying to make a buck from his fiddle or harmonica, was at that moment syncopated. And it all went into Junior’s ears and hands and came out again, jumbled perhaps with Mr. Mozart’s music or whoever was on the rack that day for him to torture, and maybe with some verbal help from the wise guy next door, the result might be a song that someday might sell like hotcakes and cross the ocean too, until the whole world was playing and whistling it and some of the bums whose parents had despaired of them became very rich indeed, and the parents frowned and learned to tap their feet too, and moved uptown, where, thanks to their one very shrewd investment in a musical black box, they’d never have to work again. The piano lessons might have been wasted, but the hooky lessons were pure gold.

Or were the piano lessons really wasted? One of the proudest claims made for the American standards is that they were good music written by real musicians, however they got there, whether by studying at the best schools, like Kern and Rodgers, or by just listening, like Irving Berlin. Berlin never did learn the piano, but could spot a wrong note on the next block.

The school of “just listening” received an endorsement from the arrival of jazz in those years. The best jazz musicians created intricate harmonies without benefit of pencil or paper—disciplines that could take years to master at school. Classical lessons were still useful because they taught good from bad and what was good about good.

But playing hooky was vital—not just at the piano, playing Chopin and Brahms in ragtime, but playing hooky from the piano, just walking around and listening to the music of the city itself, which was experiencing a creative transformation right under these players’ ears.

The same wave of good luck that had brought so many eastern European Jews to New York had also brought enough Southern blacks to mount a Harlem renaissance, and just like that, two of the principal ingredients had arrived. The standards have actually been referred to as a Jewish response to black music, but this definition is a loaded compliment that neither party has rushed to claim. With such praise, Jews never know whether to take a bow or duck. In a safe house like this book, it is the highest compliment I can think of. But in the mouth of a WASP supremacist like Henry Ford, “Jewish” meant un- American and subversive, so don’t wave that compliment around or it might explode; and for blacks it just meant more of the minstrel-show syndrome. There go those darkies, making music again, haven’t they got a great sense of rhythm? As outsiders, both Jews and blacks had been positively expected to entertain, but when they did so, it automatically became a second-class thing to do. Show biz in general was the ultimate club that accepted Groucho Marx and invited his scorn.

Music is not produced by whole groups, but by one genius at a time, and it may be significant that the two families that gave us Irving Berlin and George Gershwin both fled Russia on the same great wave of czarist pogroms, only to find American black people not only singing about a similar experience, but using the Hebrew Bible as their text.

Blacks, too, had been to heaven and back. They had found the promised land in the form of emancipation, and for a few giddy years the taste of freedom had been all the milk and honey they needed. But when they (and the white man) woke up, they realized nothing much had changed. The slaves had been moved to another part of the ledger. They would still be working for the boss, the pharaoh, but they would have to look for their own food and lodging now and pay for it out of their still-empty pockets. And somehow the boss seemed to have multiplied to include any white man who wanted a shoe shine or simply a glass of water. Just say the word “boy” to any African American, even today, and he’ll remember.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

From Irving Berlin to Cy Coleman, from Tin Pan Alley to the MGM soundstages, the Golden Age of the American song embodied all that was cool, sexy, and sophisticated in popular culture. Critically acclaimed writer Sheed has crafted an authoritative history of that era.