The Huntsman: A Memoir of Life, Love, and Olive Oil in the South of France

Autor Whitney Terrellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2002 – vârsta de la 18 ani

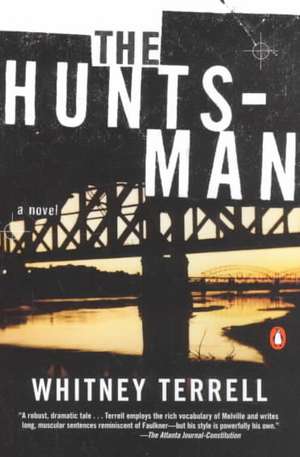

When a young debutante's body is pulled from the Missouri River, the inhabitants of Kansas City-a metropolis fractured by class division-are forced to examine their own buried history. At the center of the intrigue is Booker Short, a bitter young black man who came to town bearing a grudge about the past. His ascent into white Kansas City society, his romance with the young and wealthy Clarissa Sayers, and his involvement in her death polarize the city and lead to the final, shocking revelation of the wrong that Booker has come to avenge. With razor-sharp detail that presents the city as a character as vivid as the people living there, Whitney Terrell explores a divided society with unflinching insight.

Preț: 128.56 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 193

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.60€ • 25.75$ • 20.35£

24.60€ • 25.75$ • 20.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780142001318

ISBN-10: 0142001317

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 132 x 199 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Locul publicării:New York, United States

ISBN-10: 0142001317

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 132 x 199 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Locul publicării:New York, United States

Recenzii

"An exercise in literary prowess laced with long patches of history, simmering tensions and complex questions of betrayal and trust between and among races, classes, and families." —Chicago Tribune

"A masterful, surprising first novel, Faulknerian in its tone and structure, by a fine new storyteller." —Kirkus Reviews

"A robust, dramatic tale.... Terrell employs the rich vocabulary of Melville, and writes long, muscular sentences reminiscent of Faulkner—but his style is powerfully his own." The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

"A masterful, surprising first novel, Faulknerian in its tone and structure, by a fine new storyteller." —Kirkus Reviews

"A robust, dramatic tale.... Terrell employs the rich vocabulary of Melville, and writes long, muscular sentences reminiscent of Faulkner—but his style is powerfully his own." The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Notă biografică

Whitney Terrell was born and raised in Kansas City. His debut novel was a New York Times Notable Book. He is the New Letters writer in residence at the University of MissouriߝKansas City.

Extras

The Huntsman, Chapter One

FOR TWO GENERATIONS in the city's life there had not been much comment about its river. The populace moved southward from its banks into rolling hills and finally board-flat prairie, easily corralled, paved, and developed into suburban plots. Iron-gray and sinuous, banks heaped with deadfall and bright flecks of plastic trash, fish poisoned, docks crumbling, stinking of loam and rot, the river seemed an uncomfortable reminder of a gothic past when life had not been so clean. Bums lived along the river within sight of the mayor's office, a paper mill and several chemical companies rimmed the levee, and on the east side, the river flowed past housing projects for the poor. Most Kansas Citians never saw these things. Once every three years or so, some young reporter at the Star would get spring fever and spend the day riding upriver on an empty grain barge. In the morning, citizens at their breakfast tables held up bright color photos of the river's wide expanse and read a breathless article invoking Twain and explaining, to everyone's amazement, that barge traffic still existed. In fact, barges (this year's article read) transport one and a half million tons of cargo annually and are cheaper than trucks or rail.

"Now there's some decent reporting!" Mercury Chapman exclaimed, tapping the article with his fork. "Tells you how things work, instead of just writing up the next moronic car wreck. It's not that I don't have sympathy for any poor bastard has to die like that, but what good's the sympathy of a stranger? When I die...Lilly, what's the plan around here for when I die?" he shouted, suddenly rearing from his seat.

"The plan is, you do it after three o'clock." Lilly Washington glided through the porch door and retrieved the pitcher of milk so it wouldn't spoil. She had cooked for Mercury for thirty years, the last ten since his wife's death, and in the mornings she had business to administer. "At three o'clock the roof man's coming about that leak, and you've got to be here to show him around. Wednesdays are when I get my hair done."

"Ha!" Mercury said, sitting down.

"You've got shaving cream in your ear." Lilly's crisp lemon pantsuit darted, finchlike, into the kitchen's gloom.

"Ha!" Mercury said, rearing again for effect. The small comedy pleased him. He had talked to himself for most of his adult life, preferring to communicate by way of competing monologues rather than formal conversation, wielding the non sequitur and selective deafness like a surgeon's blade. His wife had been a formidable competitor in this running gag-in talk he found most men lugubrious-and it had been the boon of his widowerhood to discover Lilly's abilities in the field. Chattering to himself in an empty house, he would've taken his life by his own hand. "Decent reporting!" he repeated. "How much gloom is in the paper, and how much wonder all around? What about phones? You can call China by a machine on the wall, have been able to for thirty years, but who knows how it works? Or where clean water comes from, or how the TV signal goes out? How does beef get to market? Who built the Broadway Bridge? All Henry puts in here is sports, death, and politics: nothing for the common man. That's what I'm going to tell him, and watch the look on his fat Texas face...." Henry Latham was the president of the Kansas City Star, and Mercury often invited him bass fishing on weekends. He shook the paper and gazed past his Wolferman's English muffin at a photograph of the river's broad and muddy flow, a scalloped line of cottonwoods in the background.

"I like to hear that river's got a use still yet," he said, raising his voice so Lilly could hear him in the kitchen. "Booker and I went goose hunting once right along her banks, down near old Pete Martin's place. We laid out in a muddy field."

A snort of disapproval disturbed the pantry. The words "That's one way to camouflage a boy that black" reached Mercury's ears.

"Maybe he built a raft and went downriver," Mercury answered sadly, as if he had not heard a thing. "Floated clean away."

That same morning, sixty miles east of Mercury's cool, porch-flanked house on the 500 block of Highland Drive, Stan Granger headed out to check his lines. Dredging, dikes, and levees had transformed the Missouri River from a wandering, swampy titan a mile or two in width to little more than a drainage ditch (nostalgics said), at best a half mile from bank to bank. People believed that the Mighty Mo would never flood again, her mythic connection with great rivers from Abraham's time forward removed, like a stinger, by the Corps of Engineers. Still, outside Kansas City, the river flowed somnolent and muscular, centuryless, churning on without the permission of man's belief. At thirty-three, Stan Granger had acquired the habits of a much older man, a loner who fished more by habit than for useful trade. He had lost the necessity of words. Days passed in bundles when he did not speak, and as he hauled his trot line outside Waterloo, the town where he lived, his mind brooded with the same glinting, continuous flow as the river, its steady and unbroken stream of action unappended to so flimsy a vehicle as speech. So when he saw the trot line bellied far too deeply between the oak trunk and the anchor buoy a hundred yards offshore, he did not think it. He quartered his skiff against the current, set the line over his oarlock, and slid along it patiently, lifting and rebaiting the hooks that hung from steel-tipped leaders. He had caught a drum and two small catfish, and he broke their backs along the gunwales and dropped them on the skiff's floor. The closer he got to the trot line's middle, the harder the work became: the line hitched and popped jerkily along the galvanized oarlock, the weight pulled his gunwale down, and the river entered in a thin, gruel-like stream. Stan shifted his body away, grunting, to keep the gunwale up. He still did not think it but merely followed from one action to the next, each determining perfectly its successor, and when the weight and current grew too strong, he freed the line from the oarlock and played it by hand. The river darkened the flannel arms of his shirt. At the height of this ballet, his elbows bent and he thrust his chin beyond the gunwale, appearing from a distance to be ready to spring a handstand in the long, bright scarf of river, and then he set his back and tumbled a dead woman's body into his boat. Leaders trailed after it like roots, and Stan cut them one by one with his knife, just past the steel.

The corpse's head rested against the skiff's middle seat, her legs jumbled stiffly in the bow. A windbreaker had shifted rudely off her shoulders, pulling back her arms, and her breasts pressed dark aureoles against a golf shirt emblazoned with a country club's burgundy crest. She wore a khaki skirt, a needlepoint belt, and a two-toned, spiked golf shoe on her right foot, a tee stuck through the lacing flap; her left foot was bare. Her sable hair fanned the skiff's bench between Stan's knees, and her pupils, in death, had rolled backward in her head so she stared white-eyed at a cloud of starlings angling in unison against a glowing field of blue. He bent over the dead young woman without repulsion and reached beneath her shirt for a charm, which he silently unclasped. One of his hooks had caught her by the neck, and he removed it with a deft twist, leaving a glossy and bloodless wound.

Stan finished running his line. He had difficulty untangling his bait pot from the dead woman's legs, but he managed. He pulled in two carp and one more catfish and, reaching his anchored buoy, judged that if the river rose two feet more, the buoy would be submerged. None of this he put into words, but firing the skiff's outboard and heading back toward town, the dead woman's bare, finely arched foot jutting into his line of sight, he felt the need of them. He could see the small town of Waterloo banked steeply on the bluff, clapboard buildings screened by cottonwoods and willows, the railroad grade, and above everything the white spire of the church steeple. "And on a Wednesday," were the words he found. "Right on a Wednesday morning, too."

At the landing, he tossed the fish in a bucket of water and left it in the shade and walked into town wearing overalls and a dirty shirt. At the church, early choir practice had begun, and organ music drifted through the still, gnat-laden streets, and when Stan arrived at the sheriff's house-a split-level ranch along a gulley on the edge of town-the tan patrol car shimmered in the drive. The sheriff stepped out onto his balding lawn with the city paper's sports page in his hand.

"I got one," Stan said.

The sheriff glanced at him quickly and then looked back at his box score. "Dead body, you mean."

"Yeah."

"That's the first one in a year. Black fella?" Sheriff Wade Crapple was forty-five and stood a full head shorter than Stan. He had played second base both in high school and for his company team in the marines and conveyed, even while reading, a laconic preparedness for the imagined, well-struck ball. "Go on, tell me," he said. "I can do two things at once."

"She's white," Stan said. "Young. My dad used to talk about the Italians came down in the forties, but not nobody white. Not a lady."

The sheriff sniffed. "That's not what's bothering you."

"Why wouldn't it be?" Stan said. He chafed his broad hands, the necessary evasion stretching before him like a desert. "You throw a person in the river in Kansas City, and this is where they'll beach. Currents. City pitches her trash out, and it floats up at our door. I've took fifteen bodies out of that water, and that's how I looked at it-cleaning up trash-but this is the first time I've seen a face like that. Clean, young-looking. Been out golfing, I think."

"A debutante, eh?" the sheriff said. "They'll have the reporters out for that."

Stan Granger had expected a different body, if he'd expected one at all. The two were intimately connected in his memory-the dead girl, Booker Short's thin silhouette-and as the sheriff's patrol car wheeled him forward, his mind went in reverse, calling up the shadowed figure he'd seen outside old Pete Martin's cabin, two years ago last spring. Blacks of any sort were a rarity in Chapman County, and so Stan had punched his brakes, fishtailing on the gravel road, until he recognized Mercury Chapman's more familiar, whiter face, following the black one with a shovel and a rake.

He'd left them alone for a couple of days. He could not have said why, since he was caretaker of the place, except for the fleeting sense, garnered across a hundred yards of upturned soybeans, that some transaction was being conducted in which he did not care to participate. On the third day, he'd brought the water truck. The cabin stood at the end of a raised and rutted drive that split the soybean field like a dike. Beyond the cabin, a curtain of elms and pin oaks hid five hundred acres of prime duck fields bordered by a creek that, with luck, would flood them when the rains commenced. Stan had pulled the tanker in a half circle before the unshaded cabin, the screw mounts for its rain gauge blazing hot.

Seeing nobody, he'd stepped down.

"I didn't do it any," a voice said.

Wheeling, Stan had seen an empty soybean field and a washing machine colandered by target practice, and when he turned back the boy was slouched before his truck grille, head tilted, as though leaning back against a post where none in fact existed. His skin rose smooth and intensely black from the zip-collared neck of his orange shirt, though when he moved, Stan could see glimmerings of yellow in the tone and a fine, adolescent mustache on his lip. The boy glanced off toward the duck fields, sucking hard on a cigarette, and then stamped out the butt. He lifted his eyes to Stan.

"Just so's you know."

Stan's nostrils caught the distinct reek of pot, wafting in the breeze.

Then Mercury Chapman splintered through the treeline below, talking and grunting dyspeptically, as was his habit: "And so the psychiatrist tells the priest, 'I know one thing they forgot to mention in the Bible, and that's PMS.'" He labored up a short hill of thigh-deep swale, a machete dangling from his wrist. "'Hell, no, they didn't !' this preacher says. 'What about the part where Mary rides Joseph's ass clear to Bethlehem?' Hello, Stan. Why haven't you gentlemen introduced yourselves? There's goddamn enough lack of manners in the city without we start it out in the sticks. I'm of the idea we should dig this clubhouse a permanent latrine." With this he marched between them and, turning on his heel, disappeared around the cabin's corner, where Stan heard him open the door.

"Stan Granger," Stan said, holding out his hand.

The boy leaned forward from his imaginary post and gripped Stan's fingers, smiling. It was a smile of reserve, blurred in meaning, and Stan believed he'd just been invited to share amusement at the eccentricities of his employer. He closed his face.

"Booker Short is my name," the boy said when they were no longer touching. "So you work for the man?"

"I look after the club."

"Is that 'man' singular or plural?" Mercury said, rounding the cabin again. He'd exchanged the machete for the key to the water tank. "Booker is teaching me a whole nother language, Stan. All these years, and I never learned to speak jive. 'Man' means white people in general, right?"

The boy whistled. He lifted his cap and looked bleakly over the gray, long-stretching fields and the dust-streaked water truck.

"I have just heard a living person say 'jive,'" he said.

Mercury sucked the spittle off his lip. "I tell ya what, kid," he said. "Me and this old boy are gonna teach you how to fill a country water tank and work a piece-of-crap pump like Stan's got here. And you cut us some slack on vocabulary." His words were friendly, but irritation whined through his gray-tufted nose, and, as he headed for the tank, Stan saw the boy staring at him with what he judged to be (at the time, of course, before he knew Booker-though even now he did not know for sure) a look of hate.

This confusion had always troubled Stan about Booker Short-both now, as he rode in Sheriff Crapple's cruiser, and in the past. Click, like the aperture of a camera, and Booker changed from one thing to the next. His first words to Stan, "I didn't do it any," had been spoken in what Stan would have called street talk, familiar from shouting black singers on TV and pretty much how Stan expected him to speak. But later, when he said his name, the voice had been rich and melodious, each consonant savored and pronounced in the manner of black preachers or older actors, and still later, when he'd become upset over the word jive (or was it what Mercury had said about "the man," or had he even been upset at all? In retrospect, Stan still could not be sure), he'd spoken with a parodic English burr.

One person could not be so many different things before somebody decided one of them was wrong, Stan's thinking went. And furthermore, what didn't he do? Stan hadn't even known what the boy was doing out in that cabin with Mercury Chapman, a wealthy and well-connected man. Uncertainties like these made Stan's broad hands squeeze and loosen against the patrol car's polished vinyl seat. Had he in fact seen hatred in the boy's gaze? And if so, why? He still didn't know the answer to that. Nor could he say for sure what Mercury had meant when he drove with Stan to the front gate and folded three hundred dollars into his palm, saying, "It's not the job you've done. The kid needs a chance to work, so I'm going to have him look after the place. I'd appreciate it if you'd look in on him time to time." It was the first time in fifteen years that Stan had ever heard Mercury plead for anything. The older man wore a faded pink handkerchief around his head, clamped beneath a straw hat and soaked with sweat, rubber muck boots, and a tarnished service revolver on his hip. His pale-blue eyes watered in their sunburned sockets.

"I can't promise more than twice a week," Stan had told him.

"If I wanted you to baby-sit him," Mercury said, "I'd have offered more."

That had been the beginning of it: the first appearance of mystery to a man not prone to surmise. He could not remember when he had first seen his father unhook a body from his trot line or utter a low "Hep, hep" as their skiff nudged the deliquescent skull of a Mexican, snagged by his belt loop on a submerged limb. He had never puzzled over the origins of the bodies that he ferried to the river's shore, any more than he had wondered about Mercury Chapman's regular life in the city, sixty miles away. There had been, perhaps, grander times for bodies back in his father's youth: soft-fingered bookies with their heads wrapped in pillowcases, gangsters awash in tailored wool suits, their vests like corsets around their corruption, front men murdered with piano wire or lawyers punctured cleanly in the temple by a bullet. Until his own death, Stan's father had kept a set of brass knuckles as a paperweight, salvaged from a bouncer's full-length cashmere coat. But it was Stan who'd remained as witness to the river's decline, both in the fish that surfaced tumored and deformed by poison and in the increasing tawdriness of its dead. They arrived now barefoot, bony, and half starved, or wearing gaudy basketball sneakers and bright-red warm-up suits, their teeth inlaid farcically with gold. He had seen or heard tell of Vietnamese, Filipinos, Mexicans, and Chileans, but mostly there were the blacks, drug dealers, he guessed, participants in some trade violent and illegal enough to get them shot. Beyond that, however, he had avoided any curiosity about their lives. The terrors and strivings, the bereaved relatives and yellowed Polaroids stashed in cupboards of the hopeful children these corpses once had been-all the things implicit in the dead he retrieved-had never managed to disturb his peace of mind.

The truth was, until he met Booker, he'd never known a black man alive.

That spring Mercury had stayed with the boy for a week. There was a second building on the place, a converted boat shed, which had for a period of time housed a succession of itinerant farm hands who squatted there rent-free in exchange for keeping an eye on things during the off-season. This had been some fifteen years prior, before Stan was hired to do that work, and the shed had since fallen into disrepair-windows broken, raccoons and possums filling its corners with hard, white turds. Mercury and Booker worked on it by day and in the evening retired to the cabin, a strange, fanciful couple whose figures appeared matchlike across the milo fields when Stan passed by in his truck. One day, the Volvo disappeared, leaving the grounds preternaturally still. When on the second day it did not return, Stan waited until late afternoon and then parked before the driveway gate, unlocked it, and drove on in.

The sound of his truck announced him, and as he strode through the mudroom, past racks of hip waders hanging by their heels, he heard the scrape of furniture, sudden and concealed. When he entered the cabin itself, Booker sat facing him, shirtless, in a ladder-backed chair. "Hello, Stan," the boy said, his accent this time smooth and rootless.

"Why, howdy," Stan said. His greeting died when he noticed Booker's unnatural posture, his chair pulled away from the long, wax-dribbled dining table so the boy faced the door directly, his feet together and his naked shoulders braced. Stan had once felt the same uneasiness visiting a widowed farmer that he knew, and had stepped out on the back porch to find the man's hunting dog, its throat slit, wrapped in a bloodstained sheet. "Wouldn't stop barking," said the widower sanely. But Stan had sensed within that house the passage of loneliness and unreason, like a solitary summer cloud, and he felt the same presence now. "I suppose you're getting along fine," he said.

"Mmmm," the boy said, looking not at Stan but out the door.

"Doing work down at the shack?"

"Oh, yeah, lots of work."

Stan watched the boy's hands flutter and expire in his lap. The cabin had no electricity, only a portable generator run at intervals to prime the water pump, and he noticed that the gas lamps along the rafters were all lit and glowing despite the afternoon sun. The floor and kitchen were methodically neat. "I reckon we've got time to take a look down there," Stan said.

"'Time'?" Booker's teeth flashed, and he covered his mouth with his hand. "Did you say 'time'?"

"That's what I said."

"'Cause that's a good one, man-time. That's one thing Booker Short's got in spades, a lifetime supply with warranty. No deposit, no return. Everlasting flavor for your everfresh breath. The old man said you were slow, but you are an outrageously funny man...Stan."

"Do you want to go look at it or not?" Stan said.

"Let me see if I can, um...pencil you in."

The gossamer strands of spider webs that laddered the path down to the shack told Stan what he already suspected: Booker hadn't been down it since Mercury left. The boy sauntered after him with a pair of yellow earphones curled about his head, humming lightly. Stan had been certain of his impression of loneliness and fear, of some crisis that he'd interrupted, and yet Booker's response to his sympathy was ridicule. Why waste my time with that? Stan thought angrily as he pushed his way down the faded path and around the copse of evergreens that hid the shack.

At first sight, the "rehabilitation" of that structure seemed nearly complete, a surprise to Stan, who had known Mercury Chapman to be an energetic but wholly ineffectual carpenter. A new roof had been laid in and covered with rolled shingle, the window screens replaced, the stooped doorjamb torn out and roughed in square. While Stan examined these things, Booker stumbled about the piles of lumber and stacked paint cans as if he did not exist. When Stan looked again, Booker had squatted beside the warped porch with a square and a tape measure and was writing numbers on a block of pine.

"Planning to build something?" Stan asked, grinning.

The boy plucked out one earphone and laid it against his scalp. "How's that?" he asked.

"I said, are you gonna fabricate something today?" It was the same tone Stan used with Mercury, physical labor being one topic on which he presumed to condescend.

"Got to shore up the joist for this porch," Booker said. "Whole thing's rotted out underneath. I figure we can sister in the new joists beside the old, through-bolt the two together, but I'm gonna need a couple jacks to hold the thing in place. Don't feel like having a porch fall on me, out here alone."

Stan tugged up the thighs of his overalls. He said, "Let's see."

"You got a flashlight?"

"Little one on my keychain."

"Well, shimmy on underneath."

When Stan crawled out from beneath the porch, he handed Booker the tape measure. "Thirty-seven and a quarter, the joist I looked at. They might not all be the same."

Booker was sketching deftly on the woodblock, his earphones replaced. Stan set the tape on the porch. The boy seemed scrawny from growth, and his collarbone bulged awkwardly beneath his skin, too large for the slender child's biceps and sunken chest that hung below it, loose, like cloth on a rack. Sweat glistened on the small pooch of stomach above his jeans. "I guess you did most of this work yourself," Stan said.

"How's that?"

"I said I was wondering where you learned your carpentry."

Booker put down his pencil and stared levelly at Stan. "I took shop in jail."

He picked up the pencil again.

"That right?" Stan asked.

"Yep."

The porch and the small, beaten circle of grass where the two men squatted were covered, at that time of day, by the purple umbra of the nearby firs; beyond them the land fell away in shades of broken gold to a still slough overhung by cottonwoods, the figures of the two men vibrant against the cool russet of the larger trees.

"How long was you in jail for?" Stan asked.

"Sentenced to five years, served two, supposed to do the last three on parole," Booker said. "Only I'm not on parole."

"How come you're not on parole?"

"Because I jumped it," Booker said.

Stan was not aware that they had struck a bargain until some weeks later, when he was buying groceries in town. For years he'd purchased canned tins of soup, bags of rice, and sandwich meat in something like a trance, ambling through the aisles and grabbing whatever came to hand, and so it was with an obscure sense of self-deceit that he found himself at the counter not with his regular arm-basket, but pushing a cart. "Understand you've got a new neighbor," the grocer said, "got himself some trouble with the law."

"What neighbor is that?" Stan said, browsing the gum rack.

"That black boy out on Pete Martin's place."

"Didn't have any troubles when Mr. Chapman brought him down. Maybe you've seen him do something wrong since then."

"Just thought maybe you'd know about it." The grocer balanced a watermelon on his scale and grinned at the pale-blue numbered lights.

"I didn't want that," Stan said.

"No? You mean somebody else put it in your cart."

"I mean I don't want it," Stan said. "You just hand it to me, and I'll put it back."

It hadn't really been friendship, or at least Stan would not have called it that; in fact, he did not know what to call it. When he brought Booker the groceries, it was as though the boy had known that they would come, if not from Stan then from somewhere else, despite the fact that he had no car or money and lived five miles of gravel road from town. The same sense applied to the hydraulic jacks Stan had carted out from the mechanic's shop to prop up the porch: not ungratefulness, but calm acceptance without admission of debt, as though the boy had expected that if Stan didn't bring the jacks, they would just materialize somehow out of the club's five hundred acres of smartweed, sumac, and willows. Perhaps it had been the sheer conundrum of Booker Short himself. Stan's own trailer stood on four hundred feet of riverfront land due north of the cabin, fully wired, supplied with running water and a satellite dish for TV, and in the hot nights of late summer, he'd lain beneath a single sheet, the fan blowing on him from the dresser, and found himself thinking of the boy. He would have no electric fan. He would have no television to provide voices against the night. He would have no phone (though Stan, admittedly, rarely used his own). Stan himself was well acquainted with the dangers of a solitary life, had worked hard to adjust himself-he accepted, yes, the rigors of it, the barren necessity of taking himself in hand before the kitchen sink and washing his own seed down afterward with a sponge, accepted the poverty of averting his eyes from his own embarrassment. And yet he had the sense that Booker had not accepted this at all, out of either ignorance or some better quality: he was waiting for something. Perhaps it was this quality of waiting that attracted Stan. That poor kid acts like something's going to happen out here, he would think, staring at the same acoustic-tiled ceiling he had stared at for the past fifteen years. Then his heart would quicken as he thought, By God, what if it did?

An implicit moment of change had been approaching then, because in November the club members would come to hunt. The cabin was known as old Pete Martin's place by habit more than accuracy. It was supposed to have been a ski chalet. The company that invented the prefabricated chalets had gone broke selling them in Kansas City, so Dr. Martin had bought one for two hundred dollars and shipped it to Waterloo on a truck. That had been forty years ago, the wheeled conveyance of a two-story, triangular cabin into the duck flats causing such a stir that Peter Martin's name had lingered with the structure long after he'd grown too old to visit it. A club of eight dues-paying members now maintained the grounds, men in their seventies like Mercury and a few younger, satellite members sprinkled in with an eye toward the future. The older men had hunted all their lives, and for them the care and upkeep of some drafty, mouse-infected hunting lodge between the months of November and January were a ritual of unquestioned propriety. Their young manhoods had been formed in such environs, and in the fall they returned achingly to the bachelor bunks, the liquor and gun oil, and the taut gray winter skies to steal back some portion of what was gone. The cabin, decorated with antlers and bartending signs and plat-book maps, its bathroom cabinet stocked with an ancient bottle of hair tonic, seemed to them over time a place of classical permanence, not prefabricated in the least.

Stan thought about this as he stood on the Waterloo boat landing and watched the sheriff, knees shaking for balance, examine the corpse laid out in his narrow skiff. He had enjoyed a relatively private summer with Booker that first year, teaching the boy-again without Booker's asking or showing any sense of debt-how to run a trot line and handle the river from that same skiff, how to shoot squirrels, even drinking with him solemnly in the evenings, missing his regular shows at home; but the first day of the season had changed all that. This date had worried Mercury like little else Stan had ever seen. It had lain behind his desire for Booker to fix up the shack, and his decision to drive out every other week to volunteer his busy and bumbling aid. Stan had been present one day in mid-October, the three of them digging the shack a "water-saving" latrine, when Mercury leaned on his shovel and said, "In two weeks, Booker, the members who run this club are going to start showing up. They know you're living here, and the deal is, you work for all of them, not just for me."

Booker, slight and shirtless as usual, continued to dig.

"Hell and damn," Mercury said. Beneath the old man's sternum, Stan could hear the dyspepsia start to work. "I don't mean you work for me, but that's the way we've got to play it. Hell and damn. Don't get touchy with me on this, Booker; it isn't like your grandfather wrote ahead and told me I needed a hunting cabin all my own. You got any other family I'm gonna have to put up?"

Booker had stepped into the hole by now, standing nearly to his waist in the black soil, and he spoke without varying his stroke: "My grandfather knew what kind of shack this is."

"What's that?" cried Mercury. "I'd be damned interested-"

"Why, this here's a nigger shack, Mr. Chapman," Booker said, his voice curling with the bogus tones of the South. "A li'l ol' sharecropper's kind of place."

"Hell and damn!" Mercury was digging now, too, a furious paddling motion along the edges of the hole that did no more than slough dirt back in. "Son, we've had a tabernacle choir's worth of sorry humanity pass through this shack, with a whole helluva lot less promising bloodlines than you, and every last one of them white. It wasn't a matter of what their skin-"

"So that's what you do in the country," Booker said, coolly now, hardly moving his lips. "If there aren't any regular niggers around, you get them from your own kind."

"We never got them from anywhere." Stan watched the old man's high, patrician face blanch beneath his hat. He ain't seen this good an argument in years, Stan thought with admiration. Might have got hisself out of shape. "Never got them from anywhere," Mercury repeated, "but what they came looking for a place. Free to go, free to stay, free to do the work that's offered. You can piss on those that give the work, but it's not ever going to change."

The two men shoveled for a while, Booker patiently clearing out the dirt that Mercury knocked back in. Then Booker stopped and leaned on his shovel haft. "You vote Republican, Mr. Chapman?" he asked.

"I vote my interest at the box."

"And the residents of this here shack?"

"I don't like this arrangement any more than you," Mercury said. "But instead of arguing fucking politics when those old boys get down here, just try being quiet for a change."

The members convened the afternoon before opening day, thickset and hale old men with their canvas jackets and their calls packed in the same leather bags they had been left in on closing day the year before, their guns the same cheap and well-made fowling pieces they had purchased as young men, oiled and stored in inexpensive sheepskin sleeves. None was anything less than a millionaire, and they took a private, languid pleasure in every possible concealment of this fact, arriving in Buick station wagons and Oldsmobile sedans that younger, less established Kansas City men would consider fitting only for their wives. They sipped discount bourbon from plastic cups and, when they stopped at the local gun shop in Waterloo, inquired intelligently after the clerk's kin. All subscribed to the Waterloo Free Press and read it with more sentimentality than contempt. The country to them was a necessary source of stasis, a permanency that they preferred to see no one add to or subtract from, and so it was really only a matter of keeping Booker out of sight and giving them the chance to realize that nothing would change by having him there. With some embarrassment, Mercury had sent Booker to the shack at noon, and by three o'clock the lot was double-parked with cars, their doors propped open for the broadcast of the Kansas-Nebraska game. Stan found himself holding a paper cup of raw whiskey that made his throat expand, then contract. He could see, down the faded path, the pines that hid Booker's shack, and sensed among the men-Podge McGee and Hugh Singleman, busy driving stakes for the skeet machine, as well as Mercury-an uneasiness. They avoided looking that way.

Podge McGee's ancestors had run the first tavern in Kansas City, and he had continued in their taste for irregularity, never having a job, exactly, but trading in land, development rights, restaurant equipment, car parts, brass pipe, landfill, sand-anything of transient brightness and high yield. Skin cancer had gotten him twenty years back (Podge farmed his own ancestral lands south of town and had spent too many summers in open tractors). His nose had been excised, and what they had put back did not resemble a nose at all but putty spackled unevenly around two blowholes in the center of his face. With his yellow eyes blazing over this appendage, he looked like some terrible, scavenging bird. Hugh Singleman was senior vice president at Woolcombe & Lee, a foot taller and a hundred pounds heavier than Podge, whom he'd followed around since grade school commenting on the sprier man's profligate ways. In the kitchen, Edwin Coole fixed a steak marinade. He was president of Alderman, Hadley Insurance and an artist manqué whose hand-lettered signs dotted the property and whose watercolors of old Pete Martin's A-frame hung in each man's home. He was dying of prostate cancer, unbeknownst to his fellow members, but that didn't bother him so much as the fact that Mercury, his best friend, hadn't taken him into his confidence on the subject of Booker Short.

In fact, the men seemed incapable of commenting on Booker Short or anything else. They believed in the power of the final word, and so no one wanted to utter the first, a situation Mercury encouraged contentedly, his chatter diverting their attention as softly as canvas baffles on a stream: "Say, Eddie boy, you and I got to talk about this electricity problem. I think it's worth us getting wired in, rid of this dangerous gas and such, but I want to hear your ideas first-privately, see."

At four, Remy Westbrook arrived in his Oldsmobile coupe. In the name of Westbrook Lumber, Remy's ancestors had felled entire forests across the state, and their legacy was the closest thing to actual royalty that the city possessed. Remy, a hump-shouldered man with boiled-looking jowls and neck, knew this, and he estimated its worth by the niceties it allowed him to forget. "You all been out?" he asked, stepping from the car.

"Not yet today," Mercury said.

"Ah." Sighting through black bifocals, Remy unbuttoned his pants, rested one elbow on the car roof, and peed luxuriantly in the dead grass. "Heard Mercury's brought in a Negro fella, gonna put you out of business, Stan."

Hugh Singleman's stake driving stopped, and Stan felt the men listening around the yard. "I don't mind," he said.

Remy raised his eyebrows. "I would," he said. "But I ain't you. I wonder if it's too much trouble for a fella like that to come up and say hi...."

"You better put that up, Remy," Hugh Singleman said.

"What? What's that?" But then Remy-and Stan with him-followed Hugh's line of vision to the tangerine English sports car idling up the drive and Clarissa Sayers's face squinted against the white dust, leaning eagerly out the passenger side.

—Reprinted from The Huntsman by Whitney Terrell by permission of Penguin Books, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002, Whitney Terrell. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

FOR TWO GENERATIONS in the city's life there had not been much comment about its river. The populace moved southward from its banks into rolling hills and finally board-flat prairie, easily corralled, paved, and developed into suburban plots. Iron-gray and sinuous, banks heaped with deadfall and bright flecks of plastic trash, fish poisoned, docks crumbling, stinking of loam and rot, the river seemed an uncomfortable reminder of a gothic past when life had not been so clean. Bums lived along the river within sight of the mayor's office, a paper mill and several chemical companies rimmed the levee, and on the east side, the river flowed past housing projects for the poor. Most Kansas Citians never saw these things. Once every three years or so, some young reporter at the Star would get spring fever and spend the day riding upriver on an empty grain barge. In the morning, citizens at their breakfast tables held up bright color photos of the river's wide expanse and read a breathless article invoking Twain and explaining, to everyone's amazement, that barge traffic still existed. In fact, barges (this year's article read) transport one and a half million tons of cargo annually and are cheaper than trucks or rail.

"Now there's some decent reporting!" Mercury Chapman exclaimed, tapping the article with his fork. "Tells you how things work, instead of just writing up the next moronic car wreck. It's not that I don't have sympathy for any poor bastard has to die like that, but what good's the sympathy of a stranger? When I die...Lilly, what's the plan around here for when I die?" he shouted, suddenly rearing from his seat.

"The plan is, you do it after three o'clock." Lilly Washington glided through the porch door and retrieved the pitcher of milk so it wouldn't spoil. She had cooked for Mercury for thirty years, the last ten since his wife's death, and in the mornings she had business to administer. "At three o'clock the roof man's coming about that leak, and you've got to be here to show him around. Wednesdays are when I get my hair done."

"Ha!" Mercury said, sitting down.

"You've got shaving cream in your ear." Lilly's crisp lemon pantsuit darted, finchlike, into the kitchen's gloom.

"Ha!" Mercury said, rearing again for effect. The small comedy pleased him. He had talked to himself for most of his adult life, preferring to communicate by way of competing monologues rather than formal conversation, wielding the non sequitur and selective deafness like a surgeon's blade. His wife had been a formidable competitor in this running gag-in talk he found most men lugubrious-and it had been the boon of his widowerhood to discover Lilly's abilities in the field. Chattering to himself in an empty house, he would've taken his life by his own hand. "Decent reporting!" he repeated. "How much gloom is in the paper, and how much wonder all around? What about phones? You can call China by a machine on the wall, have been able to for thirty years, but who knows how it works? Or where clean water comes from, or how the TV signal goes out? How does beef get to market? Who built the Broadway Bridge? All Henry puts in here is sports, death, and politics: nothing for the common man. That's what I'm going to tell him, and watch the look on his fat Texas face...." Henry Latham was the president of the Kansas City Star, and Mercury often invited him bass fishing on weekends. He shook the paper and gazed past his Wolferman's English muffin at a photograph of the river's broad and muddy flow, a scalloped line of cottonwoods in the background.

"I like to hear that river's got a use still yet," he said, raising his voice so Lilly could hear him in the kitchen. "Booker and I went goose hunting once right along her banks, down near old Pete Martin's place. We laid out in a muddy field."

A snort of disapproval disturbed the pantry. The words "That's one way to camouflage a boy that black" reached Mercury's ears.

"Maybe he built a raft and went downriver," Mercury answered sadly, as if he had not heard a thing. "Floated clean away."

That same morning, sixty miles east of Mercury's cool, porch-flanked house on the 500 block of Highland Drive, Stan Granger headed out to check his lines. Dredging, dikes, and levees had transformed the Missouri River from a wandering, swampy titan a mile or two in width to little more than a drainage ditch (nostalgics said), at best a half mile from bank to bank. People believed that the Mighty Mo would never flood again, her mythic connection with great rivers from Abraham's time forward removed, like a stinger, by the Corps of Engineers. Still, outside Kansas City, the river flowed somnolent and muscular, centuryless, churning on without the permission of man's belief. At thirty-three, Stan Granger had acquired the habits of a much older man, a loner who fished more by habit than for useful trade. He had lost the necessity of words. Days passed in bundles when he did not speak, and as he hauled his trot line outside Waterloo, the town where he lived, his mind brooded with the same glinting, continuous flow as the river, its steady and unbroken stream of action unappended to so flimsy a vehicle as speech. So when he saw the trot line bellied far too deeply between the oak trunk and the anchor buoy a hundred yards offshore, he did not think it. He quartered his skiff against the current, set the line over his oarlock, and slid along it patiently, lifting and rebaiting the hooks that hung from steel-tipped leaders. He had caught a drum and two small catfish, and he broke their backs along the gunwales and dropped them on the skiff's floor. The closer he got to the trot line's middle, the harder the work became: the line hitched and popped jerkily along the galvanized oarlock, the weight pulled his gunwale down, and the river entered in a thin, gruel-like stream. Stan shifted his body away, grunting, to keep the gunwale up. He still did not think it but merely followed from one action to the next, each determining perfectly its successor, and when the weight and current grew too strong, he freed the line from the oarlock and played it by hand. The river darkened the flannel arms of his shirt. At the height of this ballet, his elbows bent and he thrust his chin beyond the gunwale, appearing from a distance to be ready to spring a handstand in the long, bright scarf of river, and then he set his back and tumbled a dead woman's body into his boat. Leaders trailed after it like roots, and Stan cut them one by one with his knife, just past the steel.

The corpse's head rested against the skiff's middle seat, her legs jumbled stiffly in the bow. A windbreaker had shifted rudely off her shoulders, pulling back her arms, and her breasts pressed dark aureoles against a golf shirt emblazoned with a country club's burgundy crest. She wore a khaki skirt, a needlepoint belt, and a two-toned, spiked golf shoe on her right foot, a tee stuck through the lacing flap; her left foot was bare. Her sable hair fanned the skiff's bench between Stan's knees, and her pupils, in death, had rolled backward in her head so she stared white-eyed at a cloud of starlings angling in unison against a glowing field of blue. He bent over the dead young woman without repulsion and reached beneath her shirt for a charm, which he silently unclasped. One of his hooks had caught her by the neck, and he removed it with a deft twist, leaving a glossy and bloodless wound.

Stan finished running his line. He had difficulty untangling his bait pot from the dead woman's legs, but he managed. He pulled in two carp and one more catfish and, reaching his anchored buoy, judged that if the river rose two feet more, the buoy would be submerged. None of this he put into words, but firing the skiff's outboard and heading back toward town, the dead woman's bare, finely arched foot jutting into his line of sight, he felt the need of them. He could see the small town of Waterloo banked steeply on the bluff, clapboard buildings screened by cottonwoods and willows, the railroad grade, and above everything the white spire of the church steeple. "And on a Wednesday," were the words he found. "Right on a Wednesday morning, too."

At the landing, he tossed the fish in a bucket of water and left it in the shade and walked into town wearing overalls and a dirty shirt. At the church, early choir practice had begun, and organ music drifted through the still, gnat-laden streets, and when Stan arrived at the sheriff's house-a split-level ranch along a gulley on the edge of town-the tan patrol car shimmered in the drive. The sheriff stepped out onto his balding lawn with the city paper's sports page in his hand.

"I got one," Stan said.

The sheriff glanced at him quickly and then looked back at his box score. "Dead body, you mean."

"Yeah."

"That's the first one in a year. Black fella?" Sheriff Wade Crapple was forty-five and stood a full head shorter than Stan. He had played second base both in high school and for his company team in the marines and conveyed, even while reading, a laconic preparedness for the imagined, well-struck ball. "Go on, tell me," he said. "I can do two things at once."

"She's white," Stan said. "Young. My dad used to talk about the Italians came down in the forties, but not nobody white. Not a lady."

The sheriff sniffed. "That's not what's bothering you."

"Why wouldn't it be?" Stan said. He chafed his broad hands, the necessary evasion stretching before him like a desert. "You throw a person in the river in Kansas City, and this is where they'll beach. Currents. City pitches her trash out, and it floats up at our door. I've took fifteen bodies out of that water, and that's how I looked at it-cleaning up trash-but this is the first time I've seen a face like that. Clean, young-looking. Been out golfing, I think."

"A debutante, eh?" the sheriff said. "They'll have the reporters out for that."

Stan Granger had expected a different body, if he'd expected one at all. The two were intimately connected in his memory-the dead girl, Booker Short's thin silhouette-and as the sheriff's patrol car wheeled him forward, his mind went in reverse, calling up the shadowed figure he'd seen outside old Pete Martin's cabin, two years ago last spring. Blacks of any sort were a rarity in Chapman County, and so Stan had punched his brakes, fishtailing on the gravel road, until he recognized Mercury Chapman's more familiar, whiter face, following the black one with a shovel and a rake.

He'd left them alone for a couple of days. He could not have said why, since he was caretaker of the place, except for the fleeting sense, garnered across a hundred yards of upturned soybeans, that some transaction was being conducted in which he did not care to participate. On the third day, he'd brought the water truck. The cabin stood at the end of a raised and rutted drive that split the soybean field like a dike. Beyond the cabin, a curtain of elms and pin oaks hid five hundred acres of prime duck fields bordered by a creek that, with luck, would flood them when the rains commenced. Stan had pulled the tanker in a half circle before the unshaded cabin, the screw mounts for its rain gauge blazing hot.

Seeing nobody, he'd stepped down.

"I didn't do it any," a voice said.

Wheeling, Stan had seen an empty soybean field and a washing machine colandered by target practice, and when he turned back the boy was slouched before his truck grille, head tilted, as though leaning back against a post where none in fact existed. His skin rose smooth and intensely black from the zip-collared neck of his orange shirt, though when he moved, Stan could see glimmerings of yellow in the tone and a fine, adolescent mustache on his lip. The boy glanced off toward the duck fields, sucking hard on a cigarette, and then stamped out the butt. He lifted his eyes to Stan.

"Just so's you know."

Stan's nostrils caught the distinct reek of pot, wafting in the breeze.

Then Mercury Chapman splintered through the treeline below, talking and grunting dyspeptically, as was his habit: "And so the psychiatrist tells the priest, 'I know one thing they forgot to mention in the Bible, and that's PMS.'" He labored up a short hill of thigh-deep swale, a machete dangling from his wrist. "'Hell, no, they didn't !' this preacher says. 'What about the part where Mary rides Joseph's ass clear to Bethlehem?' Hello, Stan. Why haven't you gentlemen introduced yourselves? There's goddamn enough lack of manners in the city without we start it out in the sticks. I'm of the idea we should dig this clubhouse a permanent latrine." With this he marched between them and, turning on his heel, disappeared around the cabin's corner, where Stan heard him open the door.

"Stan Granger," Stan said, holding out his hand.

The boy leaned forward from his imaginary post and gripped Stan's fingers, smiling. It was a smile of reserve, blurred in meaning, and Stan believed he'd just been invited to share amusement at the eccentricities of his employer. He closed his face.

"Booker Short is my name," the boy said when they were no longer touching. "So you work for the man?"

"I look after the club."

"Is that 'man' singular or plural?" Mercury said, rounding the cabin again. He'd exchanged the machete for the key to the water tank. "Booker is teaching me a whole nother language, Stan. All these years, and I never learned to speak jive. 'Man' means white people in general, right?"

The boy whistled. He lifted his cap and looked bleakly over the gray, long-stretching fields and the dust-streaked water truck.

"I have just heard a living person say 'jive,'" he said.

Mercury sucked the spittle off his lip. "I tell ya what, kid," he said. "Me and this old boy are gonna teach you how to fill a country water tank and work a piece-of-crap pump like Stan's got here. And you cut us some slack on vocabulary." His words were friendly, but irritation whined through his gray-tufted nose, and, as he headed for the tank, Stan saw the boy staring at him with what he judged to be (at the time, of course, before he knew Booker-though even now he did not know for sure) a look of hate.

This confusion had always troubled Stan about Booker Short-both now, as he rode in Sheriff Crapple's cruiser, and in the past. Click, like the aperture of a camera, and Booker changed from one thing to the next. His first words to Stan, "I didn't do it any," had been spoken in what Stan would have called street talk, familiar from shouting black singers on TV and pretty much how Stan expected him to speak. But later, when he said his name, the voice had been rich and melodious, each consonant savored and pronounced in the manner of black preachers or older actors, and still later, when he'd become upset over the word jive (or was it what Mercury had said about "the man," or had he even been upset at all? In retrospect, Stan still could not be sure), he'd spoken with a parodic English burr.

One person could not be so many different things before somebody decided one of them was wrong, Stan's thinking went. And furthermore, what didn't he do? Stan hadn't even known what the boy was doing out in that cabin with Mercury Chapman, a wealthy and well-connected man. Uncertainties like these made Stan's broad hands squeeze and loosen against the patrol car's polished vinyl seat. Had he in fact seen hatred in the boy's gaze? And if so, why? He still didn't know the answer to that. Nor could he say for sure what Mercury had meant when he drove with Stan to the front gate and folded three hundred dollars into his palm, saying, "It's not the job you've done. The kid needs a chance to work, so I'm going to have him look after the place. I'd appreciate it if you'd look in on him time to time." It was the first time in fifteen years that Stan had ever heard Mercury plead for anything. The older man wore a faded pink handkerchief around his head, clamped beneath a straw hat and soaked with sweat, rubber muck boots, and a tarnished service revolver on his hip. His pale-blue eyes watered in their sunburned sockets.

"I can't promise more than twice a week," Stan had told him.

"If I wanted you to baby-sit him," Mercury said, "I'd have offered more."

That had been the beginning of it: the first appearance of mystery to a man not prone to surmise. He could not remember when he had first seen his father unhook a body from his trot line or utter a low "Hep, hep" as their skiff nudged the deliquescent skull of a Mexican, snagged by his belt loop on a submerged limb. He had never puzzled over the origins of the bodies that he ferried to the river's shore, any more than he had wondered about Mercury Chapman's regular life in the city, sixty miles away. There had been, perhaps, grander times for bodies back in his father's youth: soft-fingered bookies with their heads wrapped in pillowcases, gangsters awash in tailored wool suits, their vests like corsets around their corruption, front men murdered with piano wire or lawyers punctured cleanly in the temple by a bullet. Until his own death, Stan's father had kept a set of brass knuckles as a paperweight, salvaged from a bouncer's full-length cashmere coat. But it was Stan who'd remained as witness to the river's decline, both in the fish that surfaced tumored and deformed by poison and in the increasing tawdriness of its dead. They arrived now barefoot, bony, and half starved, or wearing gaudy basketball sneakers and bright-red warm-up suits, their teeth inlaid farcically with gold. He had seen or heard tell of Vietnamese, Filipinos, Mexicans, and Chileans, but mostly there were the blacks, drug dealers, he guessed, participants in some trade violent and illegal enough to get them shot. Beyond that, however, he had avoided any curiosity about their lives. The terrors and strivings, the bereaved relatives and yellowed Polaroids stashed in cupboards of the hopeful children these corpses once had been-all the things implicit in the dead he retrieved-had never managed to disturb his peace of mind.

The truth was, until he met Booker, he'd never known a black man alive.

That spring Mercury had stayed with the boy for a week. There was a second building on the place, a converted boat shed, which had for a period of time housed a succession of itinerant farm hands who squatted there rent-free in exchange for keeping an eye on things during the off-season. This had been some fifteen years prior, before Stan was hired to do that work, and the shed had since fallen into disrepair-windows broken, raccoons and possums filling its corners with hard, white turds. Mercury and Booker worked on it by day and in the evening retired to the cabin, a strange, fanciful couple whose figures appeared matchlike across the milo fields when Stan passed by in his truck. One day, the Volvo disappeared, leaving the grounds preternaturally still. When on the second day it did not return, Stan waited until late afternoon and then parked before the driveway gate, unlocked it, and drove on in.

The sound of his truck announced him, and as he strode through the mudroom, past racks of hip waders hanging by their heels, he heard the scrape of furniture, sudden and concealed. When he entered the cabin itself, Booker sat facing him, shirtless, in a ladder-backed chair. "Hello, Stan," the boy said, his accent this time smooth and rootless.

"Why, howdy," Stan said. His greeting died when he noticed Booker's unnatural posture, his chair pulled away from the long, wax-dribbled dining table so the boy faced the door directly, his feet together and his naked shoulders braced. Stan had once felt the same uneasiness visiting a widowed farmer that he knew, and had stepped out on the back porch to find the man's hunting dog, its throat slit, wrapped in a bloodstained sheet. "Wouldn't stop barking," said the widower sanely. But Stan had sensed within that house the passage of loneliness and unreason, like a solitary summer cloud, and he felt the same presence now. "I suppose you're getting along fine," he said.

"Mmmm," the boy said, looking not at Stan but out the door.

"Doing work down at the shack?"

"Oh, yeah, lots of work."

Stan watched the boy's hands flutter and expire in his lap. The cabin had no electricity, only a portable generator run at intervals to prime the water pump, and he noticed that the gas lamps along the rafters were all lit and glowing despite the afternoon sun. The floor and kitchen were methodically neat. "I reckon we've got time to take a look down there," Stan said.

"'Time'?" Booker's teeth flashed, and he covered his mouth with his hand. "Did you say 'time'?"

"That's what I said."

"'Cause that's a good one, man-time. That's one thing Booker Short's got in spades, a lifetime supply with warranty. No deposit, no return. Everlasting flavor for your everfresh breath. The old man said you were slow, but you are an outrageously funny man...Stan."

"Do you want to go look at it or not?" Stan said.

"Let me see if I can, um...pencil you in."

The gossamer strands of spider webs that laddered the path down to the shack told Stan what he already suspected: Booker hadn't been down it since Mercury left. The boy sauntered after him with a pair of yellow earphones curled about his head, humming lightly. Stan had been certain of his impression of loneliness and fear, of some crisis that he'd interrupted, and yet Booker's response to his sympathy was ridicule. Why waste my time with that? Stan thought angrily as he pushed his way down the faded path and around the copse of evergreens that hid the shack.

At first sight, the "rehabilitation" of that structure seemed nearly complete, a surprise to Stan, who had known Mercury Chapman to be an energetic but wholly ineffectual carpenter. A new roof had been laid in and covered with rolled shingle, the window screens replaced, the stooped doorjamb torn out and roughed in square. While Stan examined these things, Booker stumbled about the piles of lumber and stacked paint cans as if he did not exist. When Stan looked again, Booker had squatted beside the warped porch with a square and a tape measure and was writing numbers on a block of pine.

"Planning to build something?" Stan asked, grinning.

The boy plucked out one earphone and laid it against his scalp. "How's that?" he asked.

"I said, are you gonna fabricate something today?" It was the same tone Stan used with Mercury, physical labor being one topic on which he presumed to condescend.

"Got to shore up the joist for this porch," Booker said. "Whole thing's rotted out underneath. I figure we can sister in the new joists beside the old, through-bolt the two together, but I'm gonna need a couple jacks to hold the thing in place. Don't feel like having a porch fall on me, out here alone."

Stan tugged up the thighs of his overalls. He said, "Let's see."

"You got a flashlight?"

"Little one on my keychain."

"Well, shimmy on underneath."

When Stan crawled out from beneath the porch, he handed Booker the tape measure. "Thirty-seven and a quarter, the joist I looked at. They might not all be the same."

Booker was sketching deftly on the woodblock, his earphones replaced. Stan set the tape on the porch. The boy seemed scrawny from growth, and his collarbone bulged awkwardly beneath his skin, too large for the slender child's biceps and sunken chest that hung below it, loose, like cloth on a rack. Sweat glistened on the small pooch of stomach above his jeans. "I guess you did most of this work yourself," Stan said.

"How's that?"

"I said I was wondering where you learned your carpentry."

Booker put down his pencil and stared levelly at Stan. "I took shop in jail."

He picked up the pencil again.

"That right?" Stan asked.

"Yep."

The porch and the small, beaten circle of grass where the two men squatted were covered, at that time of day, by the purple umbra of the nearby firs; beyond them the land fell away in shades of broken gold to a still slough overhung by cottonwoods, the figures of the two men vibrant against the cool russet of the larger trees.

"How long was you in jail for?" Stan asked.

"Sentenced to five years, served two, supposed to do the last three on parole," Booker said. "Only I'm not on parole."

"How come you're not on parole?"

"Because I jumped it," Booker said.

Stan was not aware that they had struck a bargain until some weeks later, when he was buying groceries in town. For years he'd purchased canned tins of soup, bags of rice, and sandwich meat in something like a trance, ambling through the aisles and grabbing whatever came to hand, and so it was with an obscure sense of self-deceit that he found himself at the counter not with his regular arm-basket, but pushing a cart. "Understand you've got a new neighbor," the grocer said, "got himself some trouble with the law."

"What neighbor is that?" Stan said, browsing the gum rack.

"That black boy out on Pete Martin's place."

"Didn't have any troubles when Mr. Chapman brought him down. Maybe you've seen him do something wrong since then."

"Just thought maybe you'd know about it." The grocer balanced a watermelon on his scale and grinned at the pale-blue numbered lights.

"I didn't want that," Stan said.

"No? You mean somebody else put it in your cart."

"I mean I don't want it," Stan said. "You just hand it to me, and I'll put it back."

It hadn't really been friendship, or at least Stan would not have called it that; in fact, he did not know what to call it. When he brought Booker the groceries, it was as though the boy had known that they would come, if not from Stan then from somewhere else, despite the fact that he had no car or money and lived five miles of gravel road from town. The same sense applied to the hydraulic jacks Stan had carted out from the mechanic's shop to prop up the porch: not ungratefulness, but calm acceptance without admission of debt, as though the boy had expected that if Stan didn't bring the jacks, they would just materialize somehow out of the club's five hundred acres of smartweed, sumac, and willows. Perhaps it had been the sheer conundrum of Booker Short himself. Stan's own trailer stood on four hundred feet of riverfront land due north of the cabin, fully wired, supplied with running water and a satellite dish for TV, and in the hot nights of late summer, he'd lain beneath a single sheet, the fan blowing on him from the dresser, and found himself thinking of the boy. He would have no electric fan. He would have no television to provide voices against the night. He would have no phone (though Stan, admittedly, rarely used his own). Stan himself was well acquainted with the dangers of a solitary life, had worked hard to adjust himself-he accepted, yes, the rigors of it, the barren necessity of taking himself in hand before the kitchen sink and washing his own seed down afterward with a sponge, accepted the poverty of averting his eyes from his own embarrassment. And yet he had the sense that Booker had not accepted this at all, out of either ignorance or some better quality: he was waiting for something. Perhaps it was this quality of waiting that attracted Stan. That poor kid acts like something's going to happen out here, he would think, staring at the same acoustic-tiled ceiling he had stared at for the past fifteen years. Then his heart would quicken as he thought, By God, what if it did?

An implicit moment of change had been approaching then, because in November the club members would come to hunt. The cabin was known as old Pete Martin's place by habit more than accuracy. It was supposed to have been a ski chalet. The company that invented the prefabricated chalets had gone broke selling them in Kansas City, so Dr. Martin had bought one for two hundred dollars and shipped it to Waterloo on a truck. That had been forty years ago, the wheeled conveyance of a two-story, triangular cabin into the duck flats causing such a stir that Peter Martin's name had lingered with the structure long after he'd grown too old to visit it. A club of eight dues-paying members now maintained the grounds, men in their seventies like Mercury and a few younger, satellite members sprinkled in with an eye toward the future. The older men had hunted all their lives, and for them the care and upkeep of some drafty, mouse-infected hunting lodge between the months of November and January were a ritual of unquestioned propriety. Their young manhoods had been formed in such environs, and in the fall they returned achingly to the bachelor bunks, the liquor and gun oil, and the taut gray winter skies to steal back some portion of what was gone. The cabin, decorated with antlers and bartending signs and plat-book maps, its bathroom cabinet stocked with an ancient bottle of hair tonic, seemed to them over time a place of classical permanence, not prefabricated in the least.

Stan thought about this as he stood on the Waterloo boat landing and watched the sheriff, knees shaking for balance, examine the corpse laid out in his narrow skiff. He had enjoyed a relatively private summer with Booker that first year, teaching the boy-again without Booker's asking or showing any sense of debt-how to run a trot line and handle the river from that same skiff, how to shoot squirrels, even drinking with him solemnly in the evenings, missing his regular shows at home; but the first day of the season had changed all that. This date had worried Mercury like little else Stan had ever seen. It had lain behind his desire for Booker to fix up the shack, and his decision to drive out every other week to volunteer his busy and bumbling aid. Stan had been present one day in mid-October, the three of them digging the shack a "water-saving" latrine, when Mercury leaned on his shovel and said, "In two weeks, Booker, the members who run this club are going to start showing up. They know you're living here, and the deal is, you work for all of them, not just for me."

Booker, slight and shirtless as usual, continued to dig.

"Hell and damn," Mercury said. Beneath the old man's sternum, Stan could hear the dyspepsia start to work. "I don't mean you work for me, but that's the way we've got to play it. Hell and damn. Don't get touchy with me on this, Booker; it isn't like your grandfather wrote ahead and told me I needed a hunting cabin all my own. You got any other family I'm gonna have to put up?"

Booker had stepped into the hole by now, standing nearly to his waist in the black soil, and he spoke without varying his stroke: "My grandfather knew what kind of shack this is."

"What's that?" cried Mercury. "I'd be damned interested-"

"Why, this here's a nigger shack, Mr. Chapman," Booker said, his voice curling with the bogus tones of the South. "A li'l ol' sharecropper's kind of place."

"Hell and damn!" Mercury was digging now, too, a furious paddling motion along the edges of the hole that did no more than slough dirt back in. "Son, we've had a tabernacle choir's worth of sorry humanity pass through this shack, with a whole helluva lot less promising bloodlines than you, and every last one of them white. It wasn't a matter of what their skin-"

"So that's what you do in the country," Booker said, coolly now, hardly moving his lips. "If there aren't any regular niggers around, you get them from your own kind."

"We never got them from anywhere." Stan watched the old man's high, patrician face blanch beneath his hat. He ain't seen this good an argument in years, Stan thought with admiration. Might have got hisself out of shape. "Never got them from anywhere," Mercury repeated, "but what they came looking for a place. Free to go, free to stay, free to do the work that's offered. You can piss on those that give the work, but it's not ever going to change."

The two men shoveled for a while, Booker patiently clearing out the dirt that Mercury knocked back in. Then Booker stopped and leaned on his shovel haft. "You vote Republican, Mr. Chapman?" he asked.

"I vote my interest at the box."

"And the residents of this here shack?"

"I don't like this arrangement any more than you," Mercury said. "But instead of arguing fucking politics when those old boys get down here, just try being quiet for a change."

The members convened the afternoon before opening day, thickset and hale old men with their canvas jackets and their calls packed in the same leather bags they had been left in on closing day the year before, their guns the same cheap and well-made fowling pieces they had purchased as young men, oiled and stored in inexpensive sheepskin sleeves. None was anything less than a millionaire, and they took a private, languid pleasure in every possible concealment of this fact, arriving in Buick station wagons and Oldsmobile sedans that younger, less established Kansas City men would consider fitting only for their wives. They sipped discount bourbon from plastic cups and, when they stopped at the local gun shop in Waterloo, inquired intelligently after the clerk's kin. All subscribed to the Waterloo Free Press and read it with more sentimentality than contempt. The country to them was a necessary source of stasis, a permanency that they preferred to see no one add to or subtract from, and so it was really only a matter of keeping Booker out of sight and giving them the chance to realize that nothing would change by having him there. With some embarrassment, Mercury had sent Booker to the shack at noon, and by three o'clock the lot was double-parked with cars, their doors propped open for the broadcast of the Kansas-Nebraska game. Stan found himself holding a paper cup of raw whiskey that made his throat expand, then contract. He could see, down the faded path, the pines that hid Booker's shack, and sensed among the men-Podge McGee and Hugh Singleman, busy driving stakes for the skeet machine, as well as Mercury-an uneasiness. They avoided looking that way.

Podge McGee's ancestors had run the first tavern in Kansas City, and he had continued in their taste for irregularity, never having a job, exactly, but trading in land, development rights, restaurant equipment, car parts, brass pipe, landfill, sand-anything of transient brightness and high yield. Skin cancer had gotten him twenty years back (Podge farmed his own ancestral lands south of town and had spent too many summers in open tractors). His nose had been excised, and what they had put back did not resemble a nose at all but putty spackled unevenly around two blowholes in the center of his face. With his yellow eyes blazing over this appendage, he looked like some terrible, scavenging bird. Hugh Singleman was senior vice president at Woolcombe & Lee, a foot taller and a hundred pounds heavier than Podge, whom he'd followed around since grade school commenting on the sprier man's profligate ways. In the kitchen, Edwin Coole fixed a steak marinade. He was president of Alderman, Hadley Insurance and an artist manqué whose hand-lettered signs dotted the property and whose watercolors of old Pete Martin's A-frame hung in each man's home. He was dying of prostate cancer, unbeknownst to his fellow members, but that didn't bother him so much as the fact that Mercury, his best friend, hadn't taken him into his confidence on the subject of Booker Short.

In fact, the men seemed incapable of commenting on Booker Short or anything else. They believed in the power of the final word, and so no one wanted to utter the first, a situation Mercury encouraged contentedly, his chatter diverting their attention as softly as canvas baffles on a stream: "Say, Eddie boy, you and I got to talk about this electricity problem. I think it's worth us getting wired in, rid of this dangerous gas and such, but I want to hear your ideas first-privately, see."

At four, Remy Westbrook arrived in his Oldsmobile coupe. In the name of Westbrook Lumber, Remy's ancestors had felled entire forests across the state, and their legacy was the closest thing to actual royalty that the city possessed. Remy, a hump-shouldered man with boiled-looking jowls and neck, knew this, and he estimated its worth by the niceties it allowed him to forget. "You all been out?" he asked, stepping from the car.

"Not yet today," Mercury said.

"Ah." Sighting through black bifocals, Remy unbuttoned his pants, rested one elbow on the car roof, and peed luxuriantly in the dead grass. "Heard Mercury's brought in a Negro fella, gonna put you out of business, Stan."

Hugh Singleman's stake driving stopped, and Stan felt the men listening around the yard. "I don't mind," he said.

Remy raised his eyebrows. "I would," he said. "But I ain't you. I wonder if it's too much trouble for a fella like that to come up and say hi...."

"You better put that up, Remy," Hugh Singleman said.

"What? What's that?" But then Remy-and Stan with him-followed Hugh's line of vision to the tangerine English sports car idling up the drive and Clarissa Sayers's face squinted against the white dust, leaning eagerly out the passenger side.

—Reprinted from The Huntsman by Whitney Terrell by permission of Penguin Books, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002, Whitney Terrell. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Descriere

When a young debutante's body is pulled from the river, the inhabitants of Kansas City are forced to examine their own buried history. With razor-sharp detail that presents the city as a character as vivid as the people living there, Terrell explores a divided society with unflinching insight.