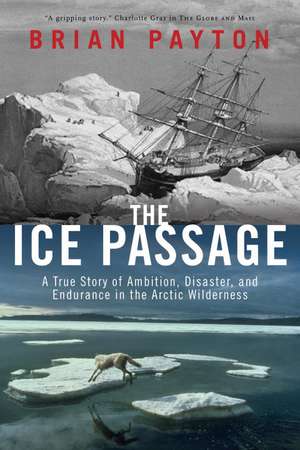

The Ice Passage: A True Story of Ambition, Disaster, and Endurance in the Arctic Wilderness

Autor Brian Paytonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2010

It begins as a mission of mercy. Four and a half years after the disappearance of Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin and his two ships, HMS Investigator sets sail in search of them. Instead of rescuing lost comrades, the Investigator’s officers and crew soon find themselves trapped in their own ordeal, facing starvation, madness, and death on the unknown Polar Sea. If only they can save themselves, they will bring back news of perhaps the greatest maritime achievement of the age: their discovery of the elusive Northwest Passage between Europe and the Orient.

In addition to their Great Success, the “Investigators” are the first Europeans to contact the Inuit of the western Arctic archipelago, and the first to record sustained observations of the local wildlife and climate. But the cost of hubris, ignorance, daring, and deceit is soon laid bare. In the face of catastrophe, a desperate rescue plan is made to send away the weakest men to meet their fate on the ice.

In a narrative rich with insight and grace, Brian Payton reconstructs the final voyage of the Investigator and the trials of her officers and crew. Drawing on long-forgotten journals, transcripts, and correspondence — some never before published — Payton weaves an astonishing tale of endurance. Along the way, he vividly evokes an Arctic wilderness we now stand to lose.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 112.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.55€ • 22.26$ • 17.92£

21.55€ • 22.26$ • 17.92£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385665339

ISBN-10: 0385665334

Pagini: 298

Dimensiuni: 154 x 231 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

ISBN-10: 0385665334

Pagini: 298

Dimensiuni: 154 x 231 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

Notă biografică

Brian Payton has written for The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe, and The Globe and Mail. He is the author of the novel Hail Mary Corner and the non-fiction narrative Shadow of the Bear: Travels in Vanishing Wilderness. Payton lives with his wife in Vancouver.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1.

DAYS OF PARADISE

July 1, 1850

He emerges as if from a shallow, anxious dream. After 150 days at sea, the brother bounds ashore on the island of Oahu. The air, redolent of tropical flora, a sultry 86 degrees. This stroll through Honolulu is his temporary release.

Johann August Miertsching, missionary of the Moravian Brotherhood, has had difficulty adjusting to his latest orders. At the urging of his superiors, the thirty-three-year-old native of Saxony committed to serving as interpreter for the Royal Navy aboard HMS Enterprise in the dual search for the lost Franklin expedition and the elusive Northwest Passage. Although he speaks several languages fluently, English is not yet among them. The voyage itself began with a fateful switch: he has not been travelling aboard the ship his superiors intended. Instead, the brother found himself temporarily assigned to HMS Investigator, consort of the Enterprise, amid rough and unruly men whose words he could scarcely comprehend. Since the Investigator's departure from Plymouth on January 20, he has spent most of his days alone in his tiny cabin, devoting himself to the study of the English and Esquimaux languages, the discipline of private prayer, the avoidance of contact with the crew.

The brother is a robust and sturdy man whose broad, earnest face belies his fundamental empathy. His eyes are dark and intelligent; his hands, thick and workmanlike—ready to build the kingdom of God. His value to this expedition, however, is not as spiritual guide. He was chosen solely for his five years' experience among the natives at the Moravian mission on the coast of Labrador. There, he mastered the Esquimaux tongue, a skill in short supply. He undertook this study to make Christ known in one of the world's most desolate places. Whether this knowledge will serve as a foundation for communication with unknown Arctic peoples more than three thousand miles to the west is at best a matter of faith. Should contact be established, however, it might lead to the rescue of Franklin and his men and, eventually, the salvation of untold ignorant flocks. But these are challenges to be met in the coming months, in the distant Polar Sea. Now is the time to revel in a world of bright sensations: the fragrance of frangipani and sandalwood, the flavour of mango and coconut, the freedom and room to roam.

This liberty culminates in a pot of tea and the company of a local missionary. This Christian fellowship is long overdue. For Miertsching, the crude ways and words of British seamen give deep and frequent offence. One exception is the ship's assistant surgeon, Henry Piers, who travels with the brother this day. Less interested in devout conversation, Piers spends the afternoon in the garden of the mission house in pursuit of dazzling butterflies.

Back in the shade, Miertsching confirms the rumours he has heard. Although government is vested in King Kamehamea III and his ministers, it is the missionaries who wield true power. Honolulu is a city of over thirty thousand Europeans, Asians, and Polynesians. Here, the natives—once famous for seemingly boundless sexual freedom—are now clad in a reasonable facsimile of European dress and more or less submit to the evangelists. To the brother, it appears as a promising example of what can be attained through the moderating influence of religion. He is, however, aware of the missionaries' reputation. They are hated by many in this port city—especially his ship's officers and crew.

As a Christian who does not deny himself the occasional drink, Miertsching wonders if the zeal of local missionaries has overwhelmed their judgment. Their prohibition of every kind of alcoholic beverage is so extreme that they refuse to baptize the child of an otherwise upright man in the habit of taking a glass of wine at luncheon. Still, Miertsching listens politely to his host, basking in the glow of conviction and certainty. In two short weeks, the Investigator will again set sail and he will be met by those same impious faces for untold months to come. In the ice and desolation of the unexplored western Arctic, he will be left to keep the fire of faith for himself, his comrades, and any Esquimaux they might encounter. But to everything there is a time, and a time to every purpose. Now is the moment to breathe deeply, to gather in the fertile green, the warming sun, the call of tropical birds.

The passage from Plymouth to Honolulu was at once isolating and fraught with incident. As far as Brother Miertsching is concerned, these memories are best forgotten. But this will never be. For even as they shadow the present, they threaten to haunt the future.

Although he had previously made the crossing from Europe to Labrador and back again, the brother is no mariner. His lack of experience, his ignorance of English, his moral rectitude all serve to separate him from the officers and crew. He found his world reduced to a cabin of seven by seven feet—a berth, washstand, desk, and chair. It was there he confessed to his God and his journal that he felt acutely alone, trapped in a floating house full of strangers.

These strangers include fifty-seven British sailors, eight officers, and their captain—the ambitious Irishman Robert John Le Mesurier McClure. Their "house" is the 422-ton Investigator, an inelegant three-masted, copper-bottomed barque measuring 118 feet in length and 28 feet in breadth. Before departing on this, her second Arctic mission, the Investigator had recently been refurbished and provisioned for three full years. Rounded at both ends to aid in ice navigation, her hull is double-thick with English oak, Canadian elm, African teak. Still more timber and iron have been bolted over her bow and stern, resulting in upwards of twenty-nine solid inches. Stripped of ornament, she is painted a solemn coat of black.

Most of her officers and crew are hardened seamen caught up in the promise of a great and noble adventure. Many are specialists in their trades—from the ice master and surgeons, down to the caulker, blacksmith, and cook. A few have prior Arctic experience. Each officer has been assigned a servant to look after his washing, and Miertsching, a civilian, was granted this status. In order to converse with the Scottish seaman assigned to him, the brother found himself reduced to gestures. The few words of German to be found among the crew came from the lips of Able Seaman Charles Anderson, a Canadian Negro who had spent time working the immigrant ships between Europe and North America.

Although Miertsching's grip on English is tenuous, there was no mistaking the nature and tenor of the heated exchanges that flew amid the creaks and groans of the heavily laden ship. After five men were thrown overboard in a storm (but quickly retrieved), a bitter, open argument erupted between the officers and captain. The brother found this insolence remarkable.

Two weeks into the voyage, everything was soaked. Throughout the ship hung a powerful, fetid stench. To fight the damp, glowing hot cannonballs were placed in the living quarters, resulting in a fire. Although quickly extinguished, several sails were burned. The following night, the men threw the first of a series of raucous parties that aggravated the brother with their singing, dancing, and laughter. Occasionally, the officers would join in the revelry with the crew. In the privacy of his cabin, Miertsching would attempt to drown out the arguments and disorder, the thump and whine of the revellers, by playing his guitar and singing German hymns. Sundays offered the only respite. Then, the fiddle was set aside, the dancers took their rest, and the uproar would subside. Paradoxically, it was on the Lord's Day that he felt most alone.

Although a majority of the men aboard claim allegiance to the Church of England, the style of religion they practise on the high seas is far below the Moravian standard. The Moravian Brotherhood—the first global, large-scale Protestant missionary effort—espouses a life of self-denial and quick obedience. Moravians place great value on personal piety, the singing of hymns, and blessed unity. Unity is fostered at religious gatherings known as lovefeasts: services of Christian fraternity that seek to strengthen the bonds of goodwill and the forgiveness of past disputes.

The deteriorating order aboard the Investigator entered a new phase with the crossing of the equator and the attendant Festival of Neptune, Sovereign of the Sea. The pious brother had never seen nor heard of anything to compare. For him, it was a cause of serious offence. Those who had yet to "cross the line" were submitted to a humiliating hazing ritual in which men's bodies were smeared with tar—which was then scraped from their skin with a rusty barrel hoop. To Miertsching, the rough, bawdy nature of the spectacle seemed positively pagan, and the indignities to which these initiates were subjected horrific. In his prior work and experience, he had been confronted with godless and insolent men. But these were angels compared to the brazen sinners surrounding him aboard the Investigator.

The disputes between the officers and captain grew more frequent and sharper in tone. Incidents of insubordination increased. One day, four men were placed under arrest, with one singled out for four dozen lashes with the cat-o'-ninetails, a whip of braided rope with nine thongs designed to inflict intense pain. A common punishment in the Royal Navy, the whippings were to ensure public humiliation and the ceremonial enforcement of authority. Some seamen have a cross tattooed on their backs to prevent them from being wantonly flogged. Although Miertsching deplores seeing a fellow human flayed, it seems the harsh rules of naval discipline are barely enough to keep them under control. In the first ten weeks since departing England, hardly a day passed without someone under arrest.

The voyage did provide moments of distraction, including occasional invitations to dine with the captain, a stroll in Patagonian hills, the view of the Southern Cross in unfamiliar skies. Miertsching enjoyed daily visits from Assistant Surgeon Piers, who tutored him in English. As there was little doctoring to do, Piers could afford time to indulge the isolated brother. A few hours of English instruction for the ship's interpreter could be crucial for their future success and survival.

On the Chilean coast, Miertsching narrowly missed transfer to the Enterprise. While the two ships lay at anchor together, the officers of the Investigator were invited to dine aboard the lead ship. There, Captain Richard Collinson, commander of the expedition, called the Esquimaux interpreter to gather his belongings and move them to his vessel. However, the night was wearing on, the whiskey flowing, and the weather growing grim. Captain Robert McClure requested that Miertsching be allowed to remain with him, aboard the Investigator, until landfall at the Sandwich Islands.

After a period of relative peace, a smouldering dispute between the officers and captain flared again. For Miertsching, it was beyond comprehension how educated and professional men could openly question their captain's authority on the high seas. How could they possibly get this ship safely through the South Pacific, let alone the Arctic ice? How could they hope to rescue Franklin and his men while at war with themselves?

As if triggered by the turmoil, sickness spread throughout the ship. Seventeen men fell ill with symptoms and conditions ranging from colds and rheumatism to "blood spitting" and colic. Miertsching was soon among them.

In this state, the men faced their first true test. The Investigator was struck at night by a squall. The sudden, sharp increase in wind—followed by an intense blast—damaged three topmasts and other critical rigging, resulting in the loss of a sail. They were foundering in the waves; everyone feared the ship would be lost. In an effort to regain command of his men and vessel, McClure flew into a rage. By morning, slackening winds allowed the crew to set sturdy yards in place of the broken mast. Control was finally regained.

At the first spare moment, McClure launched an inquiry, resulting in the trial of the officers and crew he believed responsible for losing control of the ship. The result was the arrest of First Lieutenant William Haswell. McClure promised further charges would be laid as soon as they reached the Sandwich Islands.

For Miertsching, that day could not dawn soon enough. On that day, he would trade the insolence and mayhem of the Investigator for the imagined peace and order of the Enterprise, the ship to which he was originally promised, the ship where superior accommodation, and perhaps more congenial company, awaited.

Then, as if in answer to prayer, the officers and crew rallied. With available tools and resources, they repaired much of the damage, painted, cleaned, and put the Investigator back in working order. The weather improved—along with the spirits of the crew. Drinking water was rationed to a single pint per day, but an extra measure of grog (rum and water) was frequently dispensed, further elevating the mood. The singing, dancing, and merriment that had marked the first weeks of the voyage resumed, but now the brother took less offence. His health returned. He emerged from his cabin more often and began distributing tracts on Christian values and views.

Miertsching was again invited to dine with the captain. In a ship plagued by insolence and insubordination, McClure had come to view the brother as impartial company. The brother—in a test of his English proficiency—steered the conversation on a spiritual course. He explained that he had been proselytizing among the men. At this, McClure laughed loud and long. British seamen, he assured his guest, are unlike the simple Labrador Esquimaux. They will not be so easily swayed.

At last, on Sunday, June 30, the Investigators sighted the islands of Hawaii, Maui, and Oahu. Both officers and crew lined the gunwale that day, held captive by the sight of those magnificent and storied isles, hungrily imagining the pleasures awaiting there. It seemed a paradise in which to loosen one's shirt and belt, a place to wallow at the warm belly of the world before turning north to face the ice. The brother, too, was moved by the lush spectacle before them. He felt drawn, not by baser instincts, but by the sound of church bells pealing and the sight of dark-skinned natives, dressed in white, on their way to worship.

The clear and brilliant sky rains down taxing heat. Regardless, Miertsching takes a carriage tour of the surrounding countryside to exercise his liberty. He revels in the abundance: lowlands crowded with breadfruit and banana, orderly plantations of familiar European fruits and vegetables arrayed on the hillsides above. It is, he observes, a verdant land of extraordinary beauty. As the brother takes in the sights with local religious leaders, the rest of the Investigator's officers and crew are scattered across the city and beach below, engaged in a wholly different sort of leave.

With a determination fuelled by over four months at sea, the men quickly set about violating the numerous prohibitions declared by local missionaries. They have heard rumours that pale-skinned men are favoured by native ladies. First Mate Hubert Sainsbury, a particularly fair member of the ship's company, promptly tests the theory. He sits down next to a fetching native girl spied along the side of the road. Much to the amazement of his comrades, his face is soon being stroked adoringly.

While some men find their way straight into the arms of women, others are determined to get to the bottom of a cask. Many are incapacitated with drink; five will soon require treatment for venereal disease. Such behaviour is officially discouraged but wholly expected of men who may be without for several years to come. One group of seamen get their hands on a team of horses, which they ride back and forth along the sugar sand beach at a gallop, raising hell en route. Caught up in the exuberance of freedom, they ride and run without boots, cutting their tender feet. Half a dozen men recreate with such intensity that they collapse—requiring several days' recovery.

Out in the harbour, within the humid confines of the ship, Captain McClure is in an anxious state. Upon arriving in Honolulu, he discovered that his consort, the Enterprise, had left the day before his arrival. If the Enterprise reaches the ice first, McClure believes, Collinson will press on—and succeed—without him.

He turns his attention to the prosecution of First Lieutenant Haswell in a five-hour court of inquiry. The ship is bound for uncharted Arctic waters; insolence and insubordination will not be tolerated. After much debate, McClure is reluctantly persuaded to reinstate the accused after extracting a public pledge of obedience from him and his fellow officers. The bitter, unassailable truth is that he has no choice. He needs these men—each and every one.

Miertsching, enjoying yet another guided carriage tour, is impressed with the rapid growth of the city. Its harbour has anchorage for two hundred ships, some of which bear prefabricated houses of wood and steel from both England and the United States. These structures pop up on shore at a rate of one a day. He also notes the rising contingent of Americans on this island, which has long been under British influence. So large has their presence grown that today, July 4—U.S. Independence Day—is celebrated openly. At noon, he attends one such party at a local seminary. There, he is handed a letter from Captain McClure. He unfolds the note and discovers that all hands are ordered to return to the ship immediately, no later than four o'clock this afternoon. The Investigator sails today.

The brother looks up at the welcoming faces of his hosts, perturbed by this news. The original plan was to rest at the Sandwich Islands for fourteen days—not four. Still, it is not his to question. These are to be his last precious hours of freedom.

Following the banquet, with its polite conversation and tart lemonade, he finds himself surrounded by missionaries at an impromptu lovefeast in honour of his parting. His temporary, spiritual family sings songs of praise and offers prayers for a safe voyage. As the brother savours one last hymn, he can't help but think of the rude company into which he is about to return, perhaps for several years. He reflects on the loneliness and isolation ahead and feels pain at this parting. It is a pain born not of fear, but resignation. He resolves to endure the isolation, danger, and possible death for a greater glory. In the saturated hues of the tropical afternoon, in the warm embrace of newfound friends, the brother receives gifts and best wishes for success in the distant Polar Sea.

The walk from the seminary to the beach is far too short. He is escorted by two brethren who, in a final gesture, place watermelons in his arms. He steps aboard the waiting boat, then slips into the sparkling harbour. Along the way, he says a small prayer to God and his angels for guidance and protection.

As his boat approaches the Investigator, he watches the crew busily prepare the ship for departure. They whistle, sing, and curse as they go about their tasks—the resulting cloud of profanity assaults his sensibilities. Once onboard, he reports to the tight-lipped captain who, in a bid to regain his composure, invites the brother for a private drink.

At forty-two, Robert McClure's hairline is in full retreat. Along the sides and back of his head, he lets grow the remaining fringe, which he combs forward at the temples. He wears a trim neck beard in the current fashion. Also known as a "scarf," it is often grown to hide a double chin. On McClure, however, it frames deep blue eyes, ruddy cheeks, and an expression both inquisitive and daring. Now, in early middle age, he has lived long enough to understand that men are offered few if any chances at greatness. The fact that his opportunity can only be seized though collaboration—by relying on others—is nothing short of maddening.

After a calming glass of wine, the captain and the brother proceed to the upper deck for roll call. There, it is revealed that three men have jumped ship, with all their belongings. A group of men who had been thrown in jail on shore have only just returned, their release secured by McClure's willingness to pay their fines. Five sick men have been transferred to another vessel for passage home; five new sailors have signed on to replace them.

By five o'clock in the afternoon, the Investigator clears Honolulu Harbour and sails in the open ocean. A strong wind pushes hard, and the Sandwich Islands, awash in amber light, rapidly shrink from view.

As night falls, the brother retires to his tiny cabin. He closes the door, reaches for his guitar, and sings hymns of hope and courage.

From the Hardcover edition.

DAYS OF PARADISE

July 1, 1850

He emerges as if from a shallow, anxious dream. After 150 days at sea, the brother bounds ashore on the island of Oahu. The air, redolent of tropical flora, a sultry 86 degrees. This stroll through Honolulu is his temporary release.

Johann August Miertsching, missionary of the Moravian Brotherhood, has had difficulty adjusting to his latest orders. At the urging of his superiors, the thirty-three-year-old native of Saxony committed to serving as interpreter for the Royal Navy aboard HMS Enterprise in the dual search for the lost Franklin expedition and the elusive Northwest Passage. Although he speaks several languages fluently, English is not yet among them. The voyage itself began with a fateful switch: he has not been travelling aboard the ship his superiors intended. Instead, the brother found himself temporarily assigned to HMS Investigator, consort of the Enterprise, amid rough and unruly men whose words he could scarcely comprehend. Since the Investigator's departure from Plymouth on January 20, he has spent most of his days alone in his tiny cabin, devoting himself to the study of the English and Esquimaux languages, the discipline of private prayer, the avoidance of contact with the crew.

The brother is a robust and sturdy man whose broad, earnest face belies his fundamental empathy. His eyes are dark and intelligent; his hands, thick and workmanlike—ready to build the kingdom of God. His value to this expedition, however, is not as spiritual guide. He was chosen solely for his five years' experience among the natives at the Moravian mission on the coast of Labrador. There, he mastered the Esquimaux tongue, a skill in short supply. He undertook this study to make Christ known in one of the world's most desolate places. Whether this knowledge will serve as a foundation for communication with unknown Arctic peoples more than three thousand miles to the west is at best a matter of faith. Should contact be established, however, it might lead to the rescue of Franklin and his men and, eventually, the salvation of untold ignorant flocks. But these are challenges to be met in the coming months, in the distant Polar Sea. Now is the time to revel in a world of bright sensations: the fragrance of frangipani and sandalwood, the flavour of mango and coconut, the freedom and room to roam.

This liberty culminates in a pot of tea and the company of a local missionary. This Christian fellowship is long overdue. For Miertsching, the crude ways and words of British seamen give deep and frequent offence. One exception is the ship's assistant surgeon, Henry Piers, who travels with the brother this day. Less interested in devout conversation, Piers spends the afternoon in the garden of the mission house in pursuit of dazzling butterflies.

Back in the shade, Miertsching confirms the rumours he has heard. Although government is vested in King Kamehamea III and his ministers, it is the missionaries who wield true power. Honolulu is a city of over thirty thousand Europeans, Asians, and Polynesians. Here, the natives—once famous for seemingly boundless sexual freedom—are now clad in a reasonable facsimile of European dress and more or less submit to the evangelists. To the brother, it appears as a promising example of what can be attained through the moderating influence of religion. He is, however, aware of the missionaries' reputation. They are hated by many in this port city—especially his ship's officers and crew.

As a Christian who does not deny himself the occasional drink, Miertsching wonders if the zeal of local missionaries has overwhelmed their judgment. Their prohibition of every kind of alcoholic beverage is so extreme that they refuse to baptize the child of an otherwise upright man in the habit of taking a glass of wine at luncheon. Still, Miertsching listens politely to his host, basking in the glow of conviction and certainty. In two short weeks, the Investigator will again set sail and he will be met by those same impious faces for untold months to come. In the ice and desolation of the unexplored western Arctic, he will be left to keep the fire of faith for himself, his comrades, and any Esquimaux they might encounter. But to everything there is a time, and a time to every purpose. Now is the moment to breathe deeply, to gather in the fertile green, the warming sun, the call of tropical birds.

The passage from Plymouth to Honolulu was at once isolating and fraught with incident. As far as Brother Miertsching is concerned, these memories are best forgotten. But this will never be. For even as they shadow the present, they threaten to haunt the future.

Although he had previously made the crossing from Europe to Labrador and back again, the brother is no mariner. His lack of experience, his ignorance of English, his moral rectitude all serve to separate him from the officers and crew. He found his world reduced to a cabin of seven by seven feet—a berth, washstand, desk, and chair. It was there he confessed to his God and his journal that he felt acutely alone, trapped in a floating house full of strangers.

These strangers include fifty-seven British sailors, eight officers, and their captain—the ambitious Irishman Robert John Le Mesurier McClure. Their "house" is the 422-ton Investigator, an inelegant three-masted, copper-bottomed barque measuring 118 feet in length and 28 feet in breadth. Before departing on this, her second Arctic mission, the Investigator had recently been refurbished and provisioned for three full years. Rounded at both ends to aid in ice navigation, her hull is double-thick with English oak, Canadian elm, African teak. Still more timber and iron have been bolted over her bow and stern, resulting in upwards of twenty-nine solid inches. Stripped of ornament, she is painted a solemn coat of black.

Most of her officers and crew are hardened seamen caught up in the promise of a great and noble adventure. Many are specialists in their trades—from the ice master and surgeons, down to the caulker, blacksmith, and cook. A few have prior Arctic experience. Each officer has been assigned a servant to look after his washing, and Miertsching, a civilian, was granted this status. In order to converse with the Scottish seaman assigned to him, the brother found himself reduced to gestures. The few words of German to be found among the crew came from the lips of Able Seaman Charles Anderson, a Canadian Negro who had spent time working the immigrant ships between Europe and North America.

Although Miertsching's grip on English is tenuous, there was no mistaking the nature and tenor of the heated exchanges that flew amid the creaks and groans of the heavily laden ship. After five men were thrown overboard in a storm (but quickly retrieved), a bitter, open argument erupted between the officers and captain. The brother found this insolence remarkable.

Two weeks into the voyage, everything was soaked. Throughout the ship hung a powerful, fetid stench. To fight the damp, glowing hot cannonballs were placed in the living quarters, resulting in a fire. Although quickly extinguished, several sails were burned. The following night, the men threw the first of a series of raucous parties that aggravated the brother with their singing, dancing, and laughter. Occasionally, the officers would join in the revelry with the crew. In the privacy of his cabin, Miertsching would attempt to drown out the arguments and disorder, the thump and whine of the revellers, by playing his guitar and singing German hymns. Sundays offered the only respite. Then, the fiddle was set aside, the dancers took their rest, and the uproar would subside. Paradoxically, it was on the Lord's Day that he felt most alone.

Although a majority of the men aboard claim allegiance to the Church of England, the style of religion they practise on the high seas is far below the Moravian standard. The Moravian Brotherhood—the first global, large-scale Protestant missionary effort—espouses a life of self-denial and quick obedience. Moravians place great value on personal piety, the singing of hymns, and blessed unity. Unity is fostered at religious gatherings known as lovefeasts: services of Christian fraternity that seek to strengthen the bonds of goodwill and the forgiveness of past disputes.

The deteriorating order aboard the Investigator entered a new phase with the crossing of the equator and the attendant Festival of Neptune, Sovereign of the Sea. The pious brother had never seen nor heard of anything to compare. For him, it was a cause of serious offence. Those who had yet to "cross the line" were submitted to a humiliating hazing ritual in which men's bodies were smeared with tar—which was then scraped from their skin with a rusty barrel hoop. To Miertsching, the rough, bawdy nature of the spectacle seemed positively pagan, and the indignities to which these initiates were subjected horrific. In his prior work and experience, he had been confronted with godless and insolent men. But these were angels compared to the brazen sinners surrounding him aboard the Investigator.

The disputes between the officers and captain grew more frequent and sharper in tone. Incidents of insubordination increased. One day, four men were placed under arrest, with one singled out for four dozen lashes with the cat-o'-ninetails, a whip of braided rope with nine thongs designed to inflict intense pain. A common punishment in the Royal Navy, the whippings were to ensure public humiliation and the ceremonial enforcement of authority. Some seamen have a cross tattooed on their backs to prevent them from being wantonly flogged. Although Miertsching deplores seeing a fellow human flayed, it seems the harsh rules of naval discipline are barely enough to keep them under control. In the first ten weeks since departing England, hardly a day passed without someone under arrest.

The voyage did provide moments of distraction, including occasional invitations to dine with the captain, a stroll in Patagonian hills, the view of the Southern Cross in unfamiliar skies. Miertsching enjoyed daily visits from Assistant Surgeon Piers, who tutored him in English. As there was little doctoring to do, Piers could afford time to indulge the isolated brother. A few hours of English instruction for the ship's interpreter could be crucial for their future success and survival.

On the Chilean coast, Miertsching narrowly missed transfer to the Enterprise. While the two ships lay at anchor together, the officers of the Investigator were invited to dine aboard the lead ship. There, Captain Richard Collinson, commander of the expedition, called the Esquimaux interpreter to gather his belongings and move them to his vessel. However, the night was wearing on, the whiskey flowing, and the weather growing grim. Captain Robert McClure requested that Miertsching be allowed to remain with him, aboard the Investigator, until landfall at the Sandwich Islands.

After a period of relative peace, a smouldering dispute between the officers and captain flared again. For Miertsching, it was beyond comprehension how educated and professional men could openly question their captain's authority on the high seas. How could they possibly get this ship safely through the South Pacific, let alone the Arctic ice? How could they hope to rescue Franklin and his men while at war with themselves?

As if triggered by the turmoil, sickness spread throughout the ship. Seventeen men fell ill with symptoms and conditions ranging from colds and rheumatism to "blood spitting" and colic. Miertsching was soon among them.

In this state, the men faced their first true test. The Investigator was struck at night by a squall. The sudden, sharp increase in wind—followed by an intense blast—damaged three topmasts and other critical rigging, resulting in the loss of a sail. They were foundering in the waves; everyone feared the ship would be lost. In an effort to regain command of his men and vessel, McClure flew into a rage. By morning, slackening winds allowed the crew to set sturdy yards in place of the broken mast. Control was finally regained.

At the first spare moment, McClure launched an inquiry, resulting in the trial of the officers and crew he believed responsible for losing control of the ship. The result was the arrest of First Lieutenant William Haswell. McClure promised further charges would be laid as soon as they reached the Sandwich Islands.

For Miertsching, that day could not dawn soon enough. On that day, he would trade the insolence and mayhem of the Investigator for the imagined peace and order of the Enterprise, the ship to which he was originally promised, the ship where superior accommodation, and perhaps more congenial company, awaited.

Then, as if in answer to prayer, the officers and crew rallied. With available tools and resources, they repaired much of the damage, painted, cleaned, and put the Investigator back in working order. The weather improved—along with the spirits of the crew. Drinking water was rationed to a single pint per day, but an extra measure of grog (rum and water) was frequently dispensed, further elevating the mood. The singing, dancing, and merriment that had marked the first weeks of the voyage resumed, but now the brother took less offence. His health returned. He emerged from his cabin more often and began distributing tracts on Christian values and views.

Miertsching was again invited to dine with the captain. In a ship plagued by insolence and insubordination, McClure had come to view the brother as impartial company. The brother—in a test of his English proficiency—steered the conversation on a spiritual course. He explained that he had been proselytizing among the men. At this, McClure laughed loud and long. British seamen, he assured his guest, are unlike the simple Labrador Esquimaux. They will not be so easily swayed.

At last, on Sunday, June 30, the Investigators sighted the islands of Hawaii, Maui, and Oahu. Both officers and crew lined the gunwale that day, held captive by the sight of those magnificent and storied isles, hungrily imagining the pleasures awaiting there. It seemed a paradise in which to loosen one's shirt and belt, a place to wallow at the warm belly of the world before turning north to face the ice. The brother, too, was moved by the lush spectacle before them. He felt drawn, not by baser instincts, but by the sound of church bells pealing and the sight of dark-skinned natives, dressed in white, on their way to worship.

The clear and brilliant sky rains down taxing heat. Regardless, Miertsching takes a carriage tour of the surrounding countryside to exercise his liberty. He revels in the abundance: lowlands crowded with breadfruit and banana, orderly plantations of familiar European fruits and vegetables arrayed on the hillsides above. It is, he observes, a verdant land of extraordinary beauty. As the brother takes in the sights with local religious leaders, the rest of the Investigator's officers and crew are scattered across the city and beach below, engaged in a wholly different sort of leave.

With a determination fuelled by over four months at sea, the men quickly set about violating the numerous prohibitions declared by local missionaries. They have heard rumours that pale-skinned men are favoured by native ladies. First Mate Hubert Sainsbury, a particularly fair member of the ship's company, promptly tests the theory. He sits down next to a fetching native girl spied along the side of the road. Much to the amazement of his comrades, his face is soon being stroked adoringly.

While some men find their way straight into the arms of women, others are determined to get to the bottom of a cask. Many are incapacitated with drink; five will soon require treatment for venereal disease. Such behaviour is officially discouraged but wholly expected of men who may be without for several years to come. One group of seamen get their hands on a team of horses, which they ride back and forth along the sugar sand beach at a gallop, raising hell en route. Caught up in the exuberance of freedom, they ride and run without boots, cutting their tender feet. Half a dozen men recreate with such intensity that they collapse—requiring several days' recovery.

Out in the harbour, within the humid confines of the ship, Captain McClure is in an anxious state. Upon arriving in Honolulu, he discovered that his consort, the Enterprise, had left the day before his arrival. If the Enterprise reaches the ice first, McClure believes, Collinson will press on—and succeed—without him.

He turns his attention to the prosecution of First Lieutenant Haswell in a five-hour court of inquiry. The ship is bound for uncharted Arctic waters; insolence and insubordination will not be tolerated. After much debate, McClure is reluctantly persuaded to reinstate the accused after extracting a public pledge of obedience from him and his fellow officers. The bitter, unassailable truth is that he has no choice. He needs these men—each and every one.

Miertsching, enjoying yet another guided carriage tour, is impressed with the rapid growth of the city. Its harbour has anchorage for two hundred ships, some of which bear prefabricated houses of wood and steel from both England and the United States. These structures pop up on shore at a rate of one a day. He also notes the rising contingent of Americans on this island, which has long been under British influence. So large has their presence grown that today, July 4—U.S. Independence Day—is celebrated openly. At noon, he attends one such party at a local seminary. There, he is handed a letter from Captain McClure. He unfolds the note and discovers that all hands are ordered to return to the ship immediately, no later than four o'clock this afternoon. The Investigator sails today.

The brother looks up at the welcoming faces of his hosts, perturbed by this news. The original plan was to rest at the Sandwich Islands for fourteen days—not four. Still, it is not his to question. These are to be his last precious hours of freedom.

Following the banquet, with its polite conversation and tart lemonade, he finds himself surrounded by missionaries at an impromptu lovefeast in honour of his parting. His temporary, spiritual family sings songs of praise and offers prayers for a safe voyage. As the brother savours one last hymn, he can't help but think of the rude company into which he is about to return, perhaps for several years. He reflects on the loneliness and isolation ahead and feels pain at this parting. It is a pain born not of fear, but resignation. He resolves to endure the isolation, danger, and possible death for a greater glory. In the saturated hues of the tropical afternoon, in the warm embrace of newfound friends, the brother receives gifts and best wishes for success in the distant Polar Sea.

The walk from the seminary to the beach is far too short. He is escorted by two brethren who, in a final gesture, place watermelons in his arms. He steps aboard the waiting boat, then slips into the sparkling harbour. Along the way, he says a small prayer to God and his angels for guidance and protection.

As his boat approaches the Investigator, he watches the crew busily prepare the ship for departure. They whistle, sing, and curse as they go about their tasks—the resulting cloud of profanity assaults his sensibilities. Once onboard, he reports to the tight-lipped captain who, in a bid to regain his composure, invites the brother for a private drink.

At forty-two, Robert McClure's hairline is in full retreat. Along the sides and back of his head, he lets grow the remaining fringe, which he combs forward at the temples. He wears a trim neck beard in the current fashion. Also known as a "scarf," it is often grown to hide a double chin. On McClure, however, it frames deep blue eyes, ruddy cheeks, and an expression both inquisitive and daring. Now, in early middle age, he has lived long enough to understand that men are offered few if any chances at greatness. The fact that his opportunity can only be seized though collaboration—by relying on others—is nothing short of maddening.

After a calming glass of wine, the captain and the brother proceed to the upper deck for roll call. There, it is revealed that three men have jumped ship, with all their belongings. A group of men who had been thrown in jail on shore have only just returned, their release secured by McClure's willingness to pay their fines. Five sick men have been transferred to another vessel for passage home; five new sailors have signed on to replace them.

By five o'clock in the afternoon, the Investigator clears Honolulu Harbour and sails in the open ocean. A strong wind pushes hard, and the Sandwich Islands, awash in amber light, rapidly shrink from view.

As night falls, the brother retires to his tiny cabin. He closes the door, reaches for his guitar, and sings hymns of hope and courage.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A gripping story... Payton's detailed and fascinating exploration of this hideous voyage into the Arctic wilderness reminds us that the North is a crucial feature of both our past and our future."

— The Globe and Mail

"A hypnotic read, fast-paced and wonderfully written."

— Roy MacGregor, author of Canadians: A Portrait of a Country and Its People

"A book of uncommon economy and power."

— John DeMont, author of Coal Black Heart

From the Hardcover edition.

— The Globe and Mail

"A hypnotic read, fast-paced and wonderfully written."

— Roy MacGregor, author of Canadians: A Portrait of a Country and Its People

"A book of uncommon economy and power."

— John DeMont, author of Coal Black Heart

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

Prologue: Reckoning

I

1. Days of Paradise

2. The White Edge

3. The Great Blue Chest

4. Possession

5. Articles of Faith

6. The Long View

7. Star of Plenty

8. Enduring Night

9. The Search

10. The Red Scarf

11. Water Sky

12. Bay of God's Mercy

II

13. Hunters, Scavengers

14. Parry's Rock

15. A Taste for Mountain Sorrel

16. The Wasting

17. The Surgeon's Report

III

18. Advent

19. Exodus

20. Show of Hands

21. Uncommon Prayer

22. Between Ships

23. Dominion

24. Restitution

25. Dissolution

Author's Note

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

From the Hardcover edition.

I

1. Days of Paradise

2. The White Edge

3. The Great Blue Chest

4. Possession

5. Articles of Faith

6. The Long View

7. Star of Plenty

8. Enduring Night

9. The Search

10. The Red Scarf

11. Water Sky

12. Bay of God's Mercy

II

13. Hunters, Scavengers

14. Parry's Rock

15. A Taste for Mountain Sorrel

16. The Wasting

17. The Surgeon's Report

III

18. Advent

19. Exodus

20. Show of Hands

21. Uncommon Prayer

22. Between Ships

23. Dominion

24. Restitution

25. Dissolution

Author's Note

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

From the Hardcover edition.