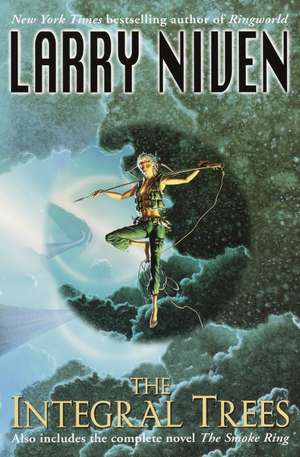

The Integral Trees: And the Smoke Ring

Autor Larry Nivenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2003

When leaving Earth, the crew of the spaceship Discipline was prepared for a routine assignment. Dispatched by the all-powerful State on a mission of interstellar exploration and colonization, Discipline was aided (and secretly spied upon) by Sharls Davis Kendy, an emotionless computer intelligence programmed to monitor the loyalty and obedience of the crew. But what they weren’t prepared for was the smoke ring–an immense gaseous envelope that had formed around a neutron star directly in their path. The Smoke Ring was home to a variety of plant and animal life-forms evolved to thrive in conditions of continual free-fall. When Discipline encountered it, something went wrong. The crew abandoned ship and fled to the unlikely space oasis.

Five hundred years later, the descendants of the Discipline crew living on the Smoke Ring no longer remember their origins. Earth is more myth than memory, and no recollection of the State remains. But Kendy remembers. And just outside the Smoke Ring, Discipline waits patiently to make contact with its wayward children.

Preț: 130.06 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 195

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.89€ • 25.83$ • 20.80£

24.89€ • 25.83$ • 20.80£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 februarie-08 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345460363

ISBN-10: 0345460367

Pagini: 459

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

ISBN-10: 0345460367

Pagini: 459

Dimensiuni: 155 x 234 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.64 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Extras

Chapter One

Quinn Tuft

Gavving could hear the rustling as his companions tunneled upward. They stayed alongside the great flat wall of the trunk. Finger-thick spine branches sprouted from the trunk, divided endlessly into wire-thin branchlets, and ultimately flowered into foliage like green cotton, loosely spun to catch every stray beam of sunlight. Some light filtered through as green twilight.

Gavving tunneled through a universe of green cotton candy.

Hungry, he reached deep into the web of branchlets and pulled out a fistful of foliage. It tasted like fibrous spun sugar. It cured hunger, but what Gavving’s belly wanted was meat. Even so, its taste was too fibrous . . . and the green of it was too brown, even at the edges of the tuft, where sunlight fell.

He ate it anyway and went on.

The rising howl of the wind told him he was nearly there. A minute later his head broke through into wind and sunlight.

The sunlight stabbed his eyes, still red and painful from this morning’s allergy attack. It always got him in the eyes and sinuses. He squinted and turned his head, and sniffled, and waited while his eyes adjusted. Then, twitchy with anticipation, he looked up.

Gavving was fourteen years old, as measured by passings of the sun behind Voy. He had never been above Quinn Tuft until now.

The trunk went straight up, straight out from Voy. It seemed to go out forever, a vast brown wall that narrowed to a cylinder, to a dark line with a gentle westward curve to it, to a point at infinity—and the point was tipped with green. The far tuft.

A cloud of brown-tinged green dropped away below him, spreading out into the main body of the tuft. Looking east, with the wind whipping his long hair forward, Gavving could see the branch emerging from its green sheath as a half-klomter of bare wood: a slender fin.

Harp’s head popped out, and his face immediately dipped again, out of the wind. Laython next, and he did the same. Gavving waited. Presently their faces lifted. Harp’s face was broad, with thick bones, its brutal strength half-concealed by golden beard. Laython’s long, dark face was beginning to sprout strands of black hair.

Harp called, “We can crawl around to lee of the trunk. East. Get out of this wind.”

The wind blew always from the west, always at gale velocities. Laython peered windward between his fingers. He bellowed, “Negative! How would we catch anything? Any prey would come right out of the wind!”

Harp squirmed through the foliage to join Laython. Gavving shrugged and did the same. He would have liked a windbreak . . . and Harp, ten years older than Gavving and Laython, was nominally in charge. It seldom worked out that way.

“There’s nothing to catch,” Harp told them. “We’re here to guard the trunk. Just because there’s a drought doesn’t mean we can’t have a flash flood. Suppose the tree brushed a pond?”

“What pond? Look around you! There’s nothing near us. Voy is too close. Harp, you’ve said so yourself!”

“The trunk blocks half our view,” Harp said mildly.

The bright spot in the sky, the sun, was drifting below the western edge of the tuft. And in that direction were no ponds, no clouds, no drifting forests . . . nothing but blue-tinged white sky split by the white line of the Smoke Ring, and on that line, a roiled knot that must be Gold.

Looking up, out, he saw more of nothing . . . faraway streamers of cloud shaping a whorl of storm . . . a glinting fleck that might indeed have been a pond, but it seemed even more distant than the green tip of the integral tree. There would be no flood.

Gavving had been six years old when the last flood came. He remembered terror, panic, frantic haste. The tribe had burrowed east along the branch, to huddle in the thin foliage where the tuft tapered into bare wood. He remembered a roar that drowned the wind, and the mass of the branch itself shuddering endlessly. Gavving’s father and two apprentice hunters hadn’t been warned in time. They had been washed into the sky.

Laython started off around the trunk, but in the windward direction. He was half out of the foliage, his long arms pulling him against the wind. Harp followed. Harp had given in, as usual. Gavving snorted and moved to join them.

It was tiring. Harp must have hated it. He was using claw sandals, but he must have suffered, even so. Harp had a good brain and a facile tongue, but he was a dwarf. His torso was short and burly; his muscular arms and legs had no reach, and his toes were mere decoration. He stood less than two meters tall. The Grad had once told Gavving, “Harp looks like the pictures of the Founders in the log. We all looked like that once.”

Harp grinned back at him, though he was puffing. “We’ll get you some claw sandals when you’re older.”

Laython grinned too, superciliously, and sprinted ahead of them both. He didn’t have to say anything. Claw sandals would only have hampered his long, prehensile toes.

Night had cut the illumination in half. Seeing was easier, with the sunglare around on the other side of Voy. The trunk was a great brown wall three klomters in circumference. Gavving looked up once and was disheartened at their lack of progress. Thereafter he kept his head bent to the wind, clawing his way across the green cotton, until he heard Laython yell.

“Dinner!”

A quivering black speck, a point to port of windward. Laython said, “Can’t tell what it is.”

Harp said, “It’s trying to miss. Looks big.”

“It’ll go around the other side! Come on!”

They crawled, fast. The quivering dot came closer. It was long and narrow and moving tail-first. The great translucent fin blurred with speed as it tried to win clear the trunk. The slender torso was slowly rotating.

The head came in view. Two eyes glittered behind the beak, one hundred and twenty degrees apart.

“Swordbird,” Harp decided. He stopped moving.

Laython called, “Harp, what are you doing?”

“Nobody in his right mind goes after a swordbird.”

“It’s still meat! And it’s probably starving too, this far in!”

Harp snorted. “Who says so? The Grad? The Grad’s full of theory, but he doesn’t have to hunt.”

The swordbird’s slow rotation exposed what should have been its third eye. What showed instead was a large, irregular, fuzzy green patch. Laython cried, “Fluff! It’s a head injury that got infected with fluff. The thing’s injured, Harp!”

“That isn’t an injured turkey, boy. It’s an injured swordbird.”

Laython was half again Harp’s size, and the Chairman’s son to boot. He was not easy to discipline. He wrapped long, strong fingers around Harp’s shoulder and said, “We’ll miss it if we wait here arguing! I say we go for Gold.” And he stood up.

The wind smashed at him. He wrapped toes and one fist in branchlets, steadied himself, and semaphored his free arm. “Hiyo! Swordbird! Meat, you copsik, meat!”

Harp made a sound of disgust.

It would surely see him, waving in that vivid scarlet blouse. Gavving thought, hopefully, We’ll miss it, and then it’ll be past. But he would not show cowardice on his first hunt.

He pulled his line loose from his back. He burrowed into the foliage to pound a spike into solid wood, and moored the line to it. The middle was attached to his waist. Nobody ever risked losing his line. A hunter who fell into the sky might still find rest somewhere, if he had his line.

The creature hadn’t seen them. Laython swore. He hurried to anchor his own line. The business end was a grapnel: hardwood from the finned end of the branch. Laython swung the grapnel round his head, yelled, and flung it out.

The swordbird must have seen, or heard. It whipped around, mouth gaping, triangular tail fluttering as it tried to gain way to starboard, to reach their side of the trunk. Starving, yes! Gavving hadn’t grasped that a creature could see him as meat until that moment.

Harp frowned. “It could work. If we’re lucky it could smash itself against the trunk.”

The swordbird seemed bigger every second: bigger than a man, bigger than a hut—all mouth and wings and tail. The tail was a translucent membrane enclosed in a V of bone spines with serrated edges. What was it doing this far in? Swordbirds fed on creatures that fed in the drifting forests, and there were few of these, so far in toward Voy. Little enough of anything. The creature did look gaunt, Gavving thought; and there was that soft green carpet over one eye.

Fluff was a green plant parasite that grew on an animal until the animal died. It attacked humans too. Everybody got it sooner or later, some more than once. But humans had the sense to stay in shadow until the fluff withered and died.

Laython could be right. A head injury, sense of direction fouled up . . . and it was meat, a mass of meat as big as the bachelors’ longhut. It must be ravenous . . . and now it turned to face them.

An isolated mouth came toward them: an elliptical field of teeth, expanding.

Laython coiled line in frantic haste. Gavving saw Harp’s line fly past him, and tearing himself out of his paralysis, he threw his own weapon.

The swordbird whipped around, impossibly fast, and snapped up Gavving’s harpoon like a tidbit. Harp whooped. Gavving froze for an instant; then his toes dug into the foliage while he hauled in line. He’d hooked it.

The creature didn’t try to escape: it was still fluttering toward them.

Harp’s grapnel grazed its side and passed on. Harp yanked, trying to hook the beast, and missed again. He reeled in line for another try.

Gavving was armpit-deep in branchlets and cotton, toes digging deeper, hands maintaining his deathgrip on the line. With eyes on him, he continued to behave as if he wanted contact with the killer beast. He bellowed, “Harp, where can I hurt it?”

“Eye sockets, I guess.”

The beast had misjudged. Its flank smashed bark from the trunk above their heads, dreadfully close. The trunk shuddered. Gavving howled in terror. Laython howled in rage and threw his grapnel ahead of it.

It grazed the swordbird’s flank. Laython pulled hard on the line and sank the hardwood tines deep in flesh.

The swordbird’s tail froze. Perhaps it was thinking things over, watching them with two good eyes while the wind pulled it west.

Laython’s line went taut. Then Gavving’s. Spine branches ripped through Gavving’s inadequate toes. Then the immense mass of the beast had pulled him into the sky.

His own throat closed tight, but he heard Laython shriek. Laython too had been pulled loose.

Torn branchlets were still clenched in Gavving’s toes. He looked down into the cushiony expanse of the tuft, wondering whether to let go and drop. But his line was still anchored . . . and wind was stronger than tide; it could blow him past the tuft, past the entire branch, out and away. Instead he crawled along the line, away from their predator-prey.

Laython wasn’t retreating. He had readied his harpoon and was waiting.

The swordbird decided. Its body snapped into a curve. The serrated tail slashed effortlessly through Gavving’s line. The swordbird flapped hard, making west now. Laython’s line went taut; then branchlets ripped and his line pulled free. Gavving snatched for it and missed.

He might have pulled himself back to safety then, but he continued to watch.

Laython poised with spear ready, his other arm waving in circles to hold his body from turning, as the predator flapped toward him. Almost alone among the creatures of the Smoke Ring, men have no wings.

The swordbird’s body snapped into a U. Its tail slashed Laython in half almost before he could move his spear. The beast’s mouth snapped shut four times, and Laython was gone. Its mouth continued to work, trying to deal with Gavving’s harpoon in its throat, as the wind carried it east.

The Scientist’s hut was like all of Quinn Tribe’s huts: live spine branches fashioned into a wickerwork cage. It was bigger than some, but there was no sense of luxury. The roof and walls were a clutter of paraphernalia stuck into the wickerwork: boards and turkey quills and red tuftberry dye for ink, tools for teaching, tools for science, and relics from the time before men left the stars.

The Scientist entered the hut with the air of a blind man. His hands were bloody to the elbows. He scraped at them with handfuls of foliage, talking under his breath. “Damn, damn drillbits. They just burrow in, no way to stop them.” He looked up. “Grad?”

“ ’Day. Who were you talking to, yourself?”

“Yes.” He scrubbed at his arms ferociously, then hurled the wads of bloody foliage away from him. “Martal’s dead. A drillbit burrowed into her. I probably killed her myself, digging it out, but she’d have died anyway . . . you can’t leave drillbit eggs. Have you heard about the expedition?”

“Yes. Barely. I can’t get anyone to tell me anything.”

The Scientist pulled a handful of foliage from the wall and tried to scrub the scalpel clean. He hadn’t looked at the Grad. “What do you think?”

The Grad had come in a fury and grown yet angrier while waiting in an empty hut. He tried to keep that out of his voice. “I think the Chairman’s trying to get rid of some citizens he doesn’t like. What I want to know is, why me?”

“The Chairman’s a fool. He thinks science could have stopped the drought.”

“Then you’re in trouble too?” The Grad got it then. “You blamed it on me.”

The Scientist looked at him at last. The Grad thought he saw guilt there, but the eyes were steady. “I let him think you were to blame, yes. Now, there are some things I want you to have—”

Incredulous laughter was his answer. “What, more gear to carry up a hundred klomters of trunk?”

“Grad . . . Jeffer. What have I told you about the tree? We’ve studied the universe together, but the most important thing in it is the tree. Didn’t I teach you that everything that lives has a way of staying near the Smoke Ring median, where there’s air and water and soil?”

“Everything but trees and men.”

“Integral trees have a way. I taught you.”

“I . . . had the idea you were only guessing . . . Oh, I see. You’re willing to bet my life.”

The Scientist’s eyes dropped. “I suppose I am. But if I’m right, there won’t be anything left but you and the people who go with you. Jeffer, this could be nothing. You could all come back with . . . whatever we need: breeding turkeys, some kind of meat animal living on the trunk, I don’t know—”

“But you don’t think so.”

“No. That’s why I’m giving you these.”

He pulled treasures from the spine-branch walls: a glassy rectangle a quarter meter by half a meter, flat enough to fit into a pack; four boxes each the size of a child’s hand. The Grad’s response was a musical “O-o-oh.”

“You’ll decide for yourself whether to tell any of the others what you’re carrying. Now let’s do one last drill session.” The Scientist plugged a cassette into the reader screen. “You won’t have much chance to study on the trunk.”

Quinn Tuft

Gavving could hear the rustling as his companions tunneled upward. They stayed alongside the great flat wall of the trunk. Finger-thick spine branches sprouted from the trunk, divided endlessly into wire-thin branchlets, and ultimately flowered into foliage like green cotton, loosely spun to catch every stray beam of sunlight. Some light filtered through as green twilight.

Gavving tunneled through a universe of green cotton candy.

Hungry, he reached deep into the web of branchlets and pulled out a fistful of foliage. It tasted like fibrous spun sugar. It cured hunger, but what Gavving’s belly wanted was meat. Even so, its taste was too fibrous . . . and the green of it was too brown, even at the edges of the tuft, where sunlight fell.

He ate it anyway and went on.

The rising howl of the wind told him he was nearly there. A minute later his head broke through into wind and sunlight.

The sunlight stabbed his eyes, still red and painful from this morning’s allergy attack. It always got him in the eyes and sinuses. He squinted and turned his head, and sniffled, and waited while his eyes adjusted. Then, twitchy with anticipation, he looked up.

Gavving was fourteen years old, as measured by passings of the sun behind Voy. He had never been above Quinn Tuft until now.

The trunk went straight up, straight out from Voy. It seemed to go out forever, a vast brown wall that narrowed to a cylinder, to a dark line with a gentle westward curve to it, to a point at infinity—and the point was tipped with green. The far tuft.

A cloud of brown-tinged green dropped away below him, spreading out into the main body of the tuft. Looking east, with the wind whipping his long hair forward, Gavving could see the branch emerging from its green sheath as a half-klomter of bare wood: a slender fin.

Harp’s head popped out, and his face immediately dipped again, out of the wind. Laython next, and he did the same. Gavving waited. Presently their faces lifted. Harp’s face was broad, with thick bones, its brutal strength half-concealed by golden beard. Laython’s long, dark face was beginning to sprout strands of black hair.

Harp called, “We can crawl around to lee of the trunk. East. Get out of this wind.”

The wind blew always from the west, always at gale velocities. Laython peered windward between his fingers. He bellowed, “Negative! How would we catch anything? Any prey would come right out of the wind!”

Harp squirmed through the foliage to join Laython. Gavving shrugged and did the same. He would have liked a windbreak . . . and Harp, ten years older than Gavving and Laython, was nominally in charge. It seldom worked out that way.

“There’s nothing to catch,” Harp told them. “We’re here to guard the trunk. Just because there’s a drought doesn’t mean we can’t have a flash flood. Suppose the tree brushed a pond?”

“What pond? Look around you! There’s nothing near us. Voy is too close. Harp, you’ve said so yourself!”

“The trunk blocks half our view,” Harp said mildly.

The bright spot in the sky, the sun, was drifting below the western edge of the tuft. And in that direction were no ponds, no clouds, no drifting forests . . . nothing but blue-tinged white sky split by the white line of the Smoke Ring, and on that line, a roiled knot that must be Gold.

Looking up, out, he saw more of nothing . . . faraway streamers of cloud shaping a whorl of storm . . . a glinting fleck that might indeed have been a pond, but it seemed even more distant than the green tip of the integral tree. There would be no flood.

Gavving had been six years old when the last flood came. He remembered terror, panic, frantic haste. The tribe had burrowed east along the branch, to huddle in the thin foliage where the tuft tapered into bare wood. He remembered a roar that drowned the wind, and the mass of the branch itself shuddering endlessly. Gavving’s father and two apprentice hunters hadn’t been warned in time. They had been washed into the sky.

Laython started off around the trunk, but in the windward direction. He was half out of the foliage, his long arms pulling him against the wind. Harp followed. Harp had given in, as usual. Gavving snorted and moved to join them.

It was tiring. Harp must have hated it. He was using claw sandals, but he must have suffered, even so. Harp had a good brain and a facile tongue, but he was a dwarf. His torso was short and burly; his muscular arms and legs had no reach, and his toes were mere decoration. He stood less than two meters tall. The Grad had once told Gavving, “Harp looks like the pictures of the Founders in the log. We all looked like that once.”

Harp grinned back at him, though he was puffing. “We’ll get you some claw sandals when you’re older.”

Laython grinned too, superciliously, and sprinted ahead of them both. He didn’t have to say anything. Claw sandals would only have hampered his long, prehensile toes.

Night had cut the illumination in half. Seeing was easier, with the sunglare around on the other side of Voy. The trunk was a great brown wall three klomters in circumference. Gavving looked up once and was disheartened at their lack of progress. Thereafter he kept his head bent to the wind, clawing his way across the green cotton, until he heard Laython yell.

“Dinner!”

A quivering black speck, a point to port of windward. Laython said, “Can’t tell what it is.”

Harp said, “It’s trying to miss. Looks big.”

“It’ll go around the other side! Come on!”

They crawled, fast. The quivering dot came closer. It was long and narrow and moving tail-first. The great translucent fin blurred with speed as it tried to win clear the trunk. The slender torso was slowly rotating.

The head came in view. Two eyes glittered behind the beak, one hundred and twenty degrees apart.

“Swordbird,” Harp decided. He stopped moving.

Laython called, “Harp, what are you doing?”

“Nobody in his right mind goes after a swordbird.”

“It’s still meat! And it’s probably starving too, this far in!”

Harp snorted. “Who says so? The Grad? The Grad’s full of theory, but he doesn’t have to hunt.”

The swordbird’s slow rotation exposed what should have been its third eye. What showed instead was a large, irregular, fuzzy green patch. Laython cried, “Fluff! It’s a head injury that got infected with fluff. The thing’s injured, Harp!”

“That isn’t an injured turkey, boy. It’s an injured swordbird.”

Laython was half again Harp’s size, and the Chairman’s son to boot. He was not easy to discipline. He wrapped long, strong fingers around Harp’s shoulder and said, “We’ll miss it if we wait here arguing! I say we go for Gold.” And he stood up.

The wind smashed at him. He wrapped toes and one fist in branchlets, steadied himself, and semaphored his free arm. “Hiyo! Swordbird! Meat, you copsik, meat!”

Harp made a sound of disgust.

It would surely see him, waving in that vivid scarlet blouse. Gavving thought, hopefully, We’ll miss it, and then it’ll be past. But he would not show cowardice on his first hunt.

He pulled his line loose from his back. He burrowed into the foliage to pound a spike into solid wood, and moored the line to it. The middle was attached to his waist. Nobody ever risked losing his line. A hunter who fell into the sky might still find rest somewhere, if he had his line.

The creature hadn’t seen them. Laython swore. He hurried to anchor his own line. The business end was a grapnel: hardwood from the finned end of the branch. Laython swung the grapnel round his head, yelled, and flung it out.

The swordbird must have seen, or heard. It whipped around, mouth gaping, triangular tail fluttering as it tried to gain way to starboard, to reach their side of the trunk. Starving, yes! Gavving hadn’t grasped that a creature could see him as meat until that moment.

Harp frowned. “It could work. If we’re lucky it could smash itself against the trunk.”

The swordbird seemed bigger every second: bigger than a man, bigger than a hut—all mouth and wings and tail. The tail was a translucent membrane enclosed in a V of bone spines with serrated edges. What was it doing this far in? Swordbirds fed on creatures that fed in the drifting forests, and there were few of these, so far in toward Voy. Little enough of anything. The creature did look gaunt, Gavving thought; and there was that soft green carpet over one eye.

Fluff was a green plant parasite that grew on an animal until the animal died. It attacked humans too. Everybody got it sooner or later, some more than once. But humans had the sense to stay in shadow until the fluff withered and died.

Laython could be right. A head injury, sense of direction fouled up . . . and it was meat, a mass of meat as big as the bachelors’ longhut. It must be ravenous . . . and now it turned to face them.

An isolated mouth came toward them: an elliptical field of teeth, expanding.

Laython coiled line in frantic haste. Gavving saw Harp’s line fly past him, and tearing himself out of his paralysis, he threw his own weapon.

The swordbird whipped around, impossibly fast, and snapped up Gavving’s harpoon like a tidbit. Harp whooped. Gavving froze for an instant; then his toes dug into the foliage while he hauled in line. He’d hooked it.

The creature didn’t try to escape: it was still fluttering toward them.

Harp’s grapnel grazed its side and passed on. Harp yanked, trying to hook the beast, and missed again. He reeled in line for another try.

Gavving was armpit-deep in branchlets and cotton, toes digging deeper, hands maintaining his deathgrip on the line. With eyes on him, he continued to behave as if he wanted contact with the killer beast. He bellowed, “Harp, where can I hurt it?”

“Eye sockets, I guess.”

The beast had misjudged. Its flank smashed bark from the trunk above their heads, dreadfully close. The trunk shuddered. Gavving howled in terror. Laython howled in rage and threw his grapnel ahead of it.

It grazed the swordbird’s flank. Laython pulled hard on the line and sank the hardwood tines deep in flesh.

The swordbird’s tail froze. Perhaps it was thinking things over, watching them with two good eyes while the wind pulled it west.

Laython’s line went taut. Then Gavving’s. Spine branches ripped through Gavving’s inadequate toes. Then the immense mass of the beast had pulled him into the sky.

His own throat closed tight, but he heard Laython shriek. Laython too had been pulled loose.

Torn branchlets were still clenched in Gavving’s toes. He looked down into the cushiony expanse of the tuft, wondering whether to let go and drop. But his line was still anchored . . . and wind was stronger than tide; it could blow him past the tuft, past the entire branch, out and away. Instead he crawled along the line, away from their predator-prey.

Laython wasn’t retreating. He had readied his harpoon and was waiting.

The swordbird decided. Its body snapped into a curve. The serrated tail slashed effortlessly through Gavving’s line. The swordbird flapped hard, making west now. Laython’s line went taut; then branchlets ripped and his line pulled free. Gavving snatched for it and missed.

He might have pulled himself back to safety then, but he continued to watch.

Laython poised with spear ready, his other arm waving in circles to hold his body from turning, as the predator flapped toward him. Almost alone among the creatures of the Smoke Ring, men have no wings.

The swordbird’s body snapped into a U. Its tail slashed Laython in half almost before he could move his spear. The beast’s mouth snapped shut four times, and Laython was gone. Its mouth continued to work, trying to deal with Gavving’s harpoon in its throat, as the wind carried it east.

The Scientist’s hut was like all of Quinn Tribe’s huts: live spine branches fashioned into a wickerwork cage. It was bigger than some, but there was no sense of luxury. The roof and walls were a clutter of paraphernalia stuck into the wickerwork: boards and turkey quills and red tuftberry dye for ink, tools for teaching, tools for science, and relics from the time before men left the stars.

The Scientist entered the hut with the air of a blind man. His hands were bloody to the elbows. He scraped at them with handfuls of foliage, talking under his breath. “Damn, damn drillbits. They just burrow in, no way to stop them.” He looked up. “Grad?”

“ ’Day. Who were you talking to, yourself?”

“Yes.” He scrubbed at his arms ferociously, then hurled the wads of bloody foliage away from him. “Martal’s dead. A drillbit burrowed into her. I probably killed her myself, digging it out, but she’d have died anyway . . . you can’t leave drillbit eggs. Have you heard about the expedition?”

“Yes. Barely. I can’t get anyone to tell me anything.”

The Scientist pulled a handful of foliage from the wall and tried to scrub the scalpel clean. He hadn’t looked at the Grad. “What do you think?”

The Grad had come in a fury and grown yet angrier while waiting in an empty hut. He tried to keep that out of his voice. “I think the Chairman’s trying to get rid of some citizens he doesn’t like. What I want to know is, why me?”

“The Chairman’s a fool. He thinks science could have stopped the drought.”

“Then you’re in trouble too?” The Grad got it then. “You blamed it on me.”

The Scientist looked at him at last. The Grad thought he saw guilt there, but the eyes were steady. “I let him think you were to blame, yes. Now, there are some things I want you to have—”

Incredulous laughter was his answer. “What, more gear to carry up a hundred klomters of trunk?”

“Grad . . . Jeffer. What have I told you about the tree? We’ve studied the universe together, but the most important thing in it is the tree. Didn’t I teach you that everything that lives has a way of staying near the Smoke Ring median, where there’s air and water and soil?”

“Everything but trees and men.”

“Integral trees have a way. I taught you.”

“I . . . had the idea you were only guessing . . . Oh, I see. You’re willing to bet my life.”

The Scientist’s eyes dropped. “I suppose I am. But if I’m right, there won’t be anything left but you and the people who go with you. Jeffer, this could be nothing. You could all come back with . . . whatever we need: breeding turkeys, some kind of meat animal living on the trunk, I don’t know—”

“But you don’t think so.”

“No. That’s why I’m giving you these.”

He pulled treasures from the spine-branch walls: a glassy rectangle a quarter meter by half a meter, flat enough to fit into a pack; four boxes each the size of a child’s hand. The Grad’s response was a musical “O-o-oh.”

“You’ll decide for yourself whether to tell any of the others what you’re carrying. Now let’s do one last drill session.” The Scientist plugged a cassette into the reader screen. “You won’t have much chance to study on the trunk.”

Descriere

For the first time, Niven's "New York Times" bestselling novel "The Integral Trees" and its sequel, "The Smoke Ring, " are available in one combined edition.

Notă biografică

Larry Nivenwas born in 1938 in Los Angeles, California. In 1956, he entered the California Institute of Technology, only to flunk out a year and a half later after discovering a bookstore jammed with used science-fiction magazines. He graduated with a B.A. in mathematics (minor in psychology) from Washburn University, Kansas, in 1962, and completed one year of graduate work before he dropped out to write. His first published story, “The Coldest Place,” appeared in the December 1964 issue ofWorlds of If. He won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1966 for “Neutron Star” and in 1974 for “The Hole Man.” The 1975 Hugo Award for Best Novelette was given toThe Borderland of Sol. His novelRingworldwon the 1970 Hugo Award for Best Novel, the 1970 Nebula Award for Best Novel, and the 1972 Ditmar, an Australian award for Best International Science Fiction.