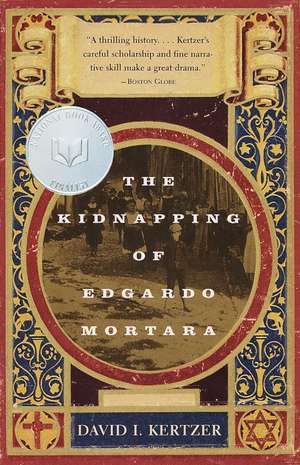

The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara

Autor David I. Kertzeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 1998

Bologna: nightfall, June 1858. A knock sounds at the door of the Jewish merchant Momolo Mortara. Two officers of the Inquisition bust inside and seize Mortara's six-year-old son, Edgardo. As the boy is wrenched from his father's arms, his mother collapses. The reason for his abduction: the boy had been secretly "baptized" by a family servant. According to papal law, the child is therefore a Catholic who can be taken from his family and delivered to a special monastery where his conversion will be completed.

With this terrifying scene, prize-winning historian David I. Kertzer begins the true story of how one boy's kidnapping became a pivotal event in the collapse of the Vatican as a secular power. The book evokes the anguish of a modest merchant's family, the rhythms of daily life in a Jewish ghetto, and also explores, through the revolutionary campaigns of Mazzini and Garibaldi and such personages as Napoleon III, the emergence of Italy as a modern national state. Moving and informative, the Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara reads as both a historical thriller and an authoritative analysis of how a single human tragedy changed the course of history.

Preț: 99.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.06€ • 19.79$ • 15.89£

19.06€ • 19.79$ • 15.89£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679768173

ISBN-10: 0679768173

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0679768173

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Recenzii

"A thrilling history... Kertzer's careful scholarship and fine narrative skill make a great drama."- Boston Globe

"A lucidly drawn, dramatic narrative. Kertzer's account reads like a courtroom drama. As shapely and surprising as fiction."- Newsday

"Brilliant... a book that has all the merits of a historical thriller."- Daily News

"A lucidly drawn, dramatic narrative. Kertzer's account reads like a courtroom drama. As shapely and surprising as fiction."- Newsday

"Brilliant... a book that has all the merits of a historical thriller."- Daily News

Notă biografică

David I. Kertzer was born in 1948 in New York City. The recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1986, he has twice been awarded, in 1985 and 1990, the Marraro Prize from the Society for Italian Historical Studies for the best work on Italian history. He is currently Paul Dupee, Jr. University Professor of Social Science and a professor of anthropology and history at Brown University. He and his family live in Providence.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

The Knock at the Door

THE KNOCK CAME at nightfall. It was Wednesday, June 23, 1858. Anna Facchini, a 23-year-old servant, descended a flight of stairs from the Mortara apartment to open the building's outer door. Before her stood a uniformed police officer and a second, middle-aged man of martial bearing.1

"Is this the home of Signor Momolo Mortara?" asked Marshal Lucidi.

Yes, Anna responded, but Signor Mortara was not there. He had gone out with his oldest son.

As the men turned away, she closed the door and returned to the apartment to report the unsettling encounter to her employer, Marianna Mortara. Marianna sat at the living room table, busily stitching, along with her twin 11-year-old daughters, Ernesta and Erminia. Her five younger children, Augusto, aged 10, Arnoldo, 9, Edgardo, 6, Ercole, 4, and Imelda, born just six months before, were already asleep. Marianna, a nervous sort anyway, wished that her husband were home.

A few minutes later, she heard sounds of feet climbing the back stairs, which could be reached through her neighbor's apartment. Marianna stopped her stitching and listened carefully. The knocking on the door confirmed her fears. She approached the door and, without touching it, asked who was there.

"It's the police," a voice said. "Let us in."

Marianna, hoping though not really believing that the policemen had simply made a mistake, told them what she prayed they did not know: they were at the back door of the same apartment they had visited just a few minutes before.

"It doesn't matter, Signora. We are police and we want to come in. Don't worry; we wish you no harm."

Marianna opened the door and let the two men in. She did not notice the rest of the papal police detail, some of whom remained on the nearby stairs while others lingered on the street below.

Pietro Lucidi, marshal in the papal carabinieri and head of the police detail, entered, with Brigadier Giuseppe Agostini, in civilian clothes, following him in. The sight of the military police of the Papal States coming inexplicably in the night filled Marianna with dread.

The Marshal, not at all happy about the mission before him, and seeing that the woman was already distraught, tried to calm her. Pulling a small sheet of paper from his jacket, he told her he needed to get certain clarifications about her family and asked her to list the names of everyone in the household, beginning with her husband and herself, and proceeding through all her children, from oldest to youngest. Marianna began to shake.

Walking home beneath Bologna's famous porticoes with Riccardo, his 13-year-old son, that pleasant June evening, Momolo was surprised to find police milling around his outside door. He hurried up to his apartment and discovered the police officer and the other strange man talking to his frightened wife.

As Momolo entered the apartment, Marianna exclaimed, "Just listen to what these men want with our family!"

Marshal Lucidi now saw that his worst fears about his mission would be realized, but felt even so a certain relief at now being able to deal with Momolo, who was, after all, a man. Again he stated that he had been given the task of determining just who was in the Mortara household. Momolo, unable to get any explanation for this ominous inquiry, proceeded to name himself, his wife, and each of his eight children.

The Marshal checked all these names on his little list. Having noted all ten members of the family, he announced that he would now like to see each of the children. His request turned Marianna's fright to terror.

Momolo pointed out Riccardo, Ernesta, and Erminia, who had gathered round their parents, but pleaded that his other children were asleep and should be left alone.

Moved, perhaps, but undeterred, the Marshal remained firm. Eventually the Mortaras led the two policemen through the door into their own bedroom, with the three oldest children and the servant trailing them in. There, on a sofa-bed, slept 6-year-old Edgardo. His parents did not yet know that on the list the Marshal had brought with him, Edgardo's name was underlined.

Lucidi told Anna to take the rest of the children out of the room. Once they had left, he turned back to Momolo and said, "Signor Mortara, I am sorry to inform you that you are the victim of betrayal."

"What betrayal?" asked Marianna.

"Your son Edgardo has been baptized," Lucidi responded, "and I have been ordered to take him with me."

Marianna's shrieks echoed through the building, prompting the policemen stationed outside to scurry into the bedroom. The older Mortara children, terrified, sneaked back in as well. Weeping hysterically, Marianna threw herself into Edgardo's bed and clutched the somnolent boy to her.

"If you want my son, you'll have to kill me first!"

"There must be some mistake," Momolo said. "My son was never baptized. . . . Who says Edgardo was baptized? Who says he has to be taken?"

"I am only acting according to orders," pleaded the Marshal. "I'm just following the Inquisitor's orders."

Lucidi despaired as the situation seemed to be slipping out of control. In his own report, he later wrote: "I hardly know how to describe the effect of that fatal announcement. I can assure you that I would have a thousand times preferred to be exposed to much more serious dangers in performing my duties than to have to witness such a painful scene."

With Marianna wailing from Edgardo's bed, Momolo insisting that it was all a horrible mistake, and the children crying, Lucidi scarcely knew what to do. Both parents got down on their knees before the discomfited Marshal, begging him in the name of humanity not to take their child from them. Bending a bit (and no doubt thinking this was all the Inquisitor's fault anyway), Lucidi offered to let Momolo accompany his son to see the Inquisitor at the nearby Convent of San Domenico.

Momolo refused, afraid to let Edgardo into the Inquisitor's hands.

Lucidi recalled: "While I waited for the desperate mother and father, overcome by a terrible agony, to return to reason so that the matter could be brought to its inevitable conclusion, various people began to arrive, either on their own or because they had been called there."

In fact, with Lucidi's permission, Momolo had sent Riccardo to alert Marianna's brother and uncle, and to fetch their elderly Jewish neighbor Bonajuto Sanguinetti, whose wealth and community position, Momolo hoped, might ward off the impending disaster.

Hurrying back to the cafe where, less than an hour before, he and his father had left them, Riccardo came upon his two uncles, Angelo Padovani, his mother's brother, and Angelo Moscato, husband of his mother's sister. Moscato later described the encounter:

"As I sat with my brother-in-law at the Caff? del Genio on via Vetturini, my nephew Riccardo Mortara came running up, in tears and disconsolate, telling me that the carabinieri were in his house, and that they wanted to kidnap his brother Edgardo."

The two men rushed to the Mortaras' apartment: "We saw the mother, devastated, and in such a sorry state that it's impossible to describe. I asked the marshal of the gendarmes to explain what was going on, and he responded that he had an order-though he never showed it to me-from the Inquisitor, Father Pier Gaetano Feletti, to take Edgardo because he had been baptized."

Marianna was "desperate, beside herself," as her brother, Angelo Padovani, recalled. "She lay stretched out on a sofa which they also used as a bed, the sofa on which Edgardo slept, holding him tightly to her chest so that no one could take him."

Trying to find some way to stop the police from making off with Edgardo, Padovani and his brother-in-law persuaded the Marshal not to remove the child before they could consult with their uncle, who lived nearby. The uncle, Marianna's father's brother, whose name was also Angelo Padovani, was still at work in the small bank he ran in the same building in which he lived.

After his nephews filled him in on the dramatic events at the Mortara home, Signor Padovani decided that their only hope was to see the Inquisitor. While the younger Padovani rushed back to inform the Marshal of the need for further delay, the other two men made their way to the convent.

At 11 p.m., they presented themselves at the forbidding gate of San Domenico and asked to be taken to the Inquisitor. Despite the hour, they were rushed up to the Inquisitor's room. They implored Father Feletti to tell them why he had ordered the police to take Edgardo. Responding in measured tones, and hoping to calm them, the Inquisitor explained that Edgardo had been secretly baptized, although by whom, or how he came to know of it, he would not say. Once word of the baptism had reached the proper authorities, they had given him the instructions that he was now carrying out: the boy was a Catholic and could not be raised in a Jewish household.

Padovani protested bitterly. It was an act of great cruelty, he said, to order a child taken from his parents without ever giving them a chance to defend themselves. Father Feletti simply responded that it was not in his power to deviate from the orders he had received. The men begged him to reveal his grounds for thinking that the child had been baptized, for no one in the family knew anything about it. The Inquisitor replied that he could give no such explanation, the matter being confidential, but that they should rest assured that everything had been done properly. It would be best for all concerned, he added, if the members of the family would simply resign themselves to what was to come. "Far from acting lightly in this matter," he told them, "I have acted in good conscience, for everything has been done punctiliously according to the sacred Canons."

Seeing that it was impossible to get Father Feletti to reconsider his order, the men pleaded with him to give the family more time before taking the boy. They asked that he suspend any action for at least a day.

"At first," Moscato later recounted, "that man of stone refused, and we had to paint a picture for him of the sad state of a mother who had another child she was nursing, of a father who was being driven almost out of his mind, and of eight [sic] children clutching at their parents' and the policemen's knees, begging them not to take their brother away from them."

Eventually, the Inquisitor did change his mind and allowed them a twenty-four-hour stay, hoping that in the meantime the distraught mother could be made to leave the apartment, thereby heading off what threatened to become an unfortunate public disturbance. He asked Moscato and Padovani to promise that no attempt would be made to help the boy escape, an assurance they gave only reluctantly.

Father Feletti later recounted what went through his mind as he weighed the risks of permitting the delay. He knew full well, he said, of the "superstitions in which the Jews are steeped," and so he feared not only that "the child might be stolen away," but indeed that he might perhaps even be "sacrificed." His was a belief shared widely in Italy at that time, for it was thought that Jews would rather murder their own children than see them grow up to be Catholic. He would take no chances. In the note he prepared for Padovani to give to Lucidi, he ordered the Marshal to keep Edgardo under constant surveillance.

Meanwhile, the vigil at the Mortara apartment continued as other friends and neighbors converged on the home. Among these was the Mortaras' 71-year-old next-door neighbor, Bonajuto Sanguinetti, like Momolo a transplant from the Jewish community of nearby Reggio Emilia, in the duchy of Modena. Sanguinetti had already gone to bed when Riccardo, after fetching his two uncles at the cafe, came to his home and told the servant what was happening.

Sanguinetti described his first reactions when his servant woke him up: "I went to the window and saw five or six carabinieri walking about under the portico, and at first I was a little confused, thinking that they had come to take one of my own grandchildren."

He rushed to the Mortaras' home: "I saw a distraught mother, bathed in tears, and a father who was tearing out his hair, while the children were down on their knees begging the policemen for mercy. It was a scene so moving I can't begin to describe it. Indeed, I even heard the police marshal, by the name of Lucidi, say that he would have rather been ordered to arrest a hundred criminals than to take that boy away."

At half past midnight, the eerie vigil at the Mortara home was interrupted by the arrival of Moscato and Padovani, brandishing the piece of paper that they had extracted from Father Feletti. Marshal Lucidi was astonished that the Jews had had any success with the Inquisitor. He had assumed that he would not be leaving the apartment that night without the boy.

"I could see," the Marshal later recalled,

that Signor Padovani was an erudite person, of dignified demeanor, a man who was looked up to and respected by his coreligionists, and they counted heavily on him. Indeed, they had good reason to do so, for it must have taken someone of great influence to obtain a stay in the decree, and in my opinion others would not have succeeded in getting one, all the more so when I learned that the order came from the highest level, and that the Father Inquisitor himself was not in a position to change it.

When the Marshal departed, he left a scene that he described as a teatro di pianto e di afflizione, a "theater of tears and affliction." Aside from the ten members of the Mortara family and the two policemen guarding Edgardo, he left behind Marianna's brother, her brother-in-law, her uncle, and two family friends.

Momolo reacted to the news of the stay with relief, saying later it gave them "a ray of hope." He was less happy, though, to discover that in putting into effect the Inquisitor's admonitions to guard Edgardo closely, the Marshal had ordered two of the policemen to remain with the child in the Mortaras' bedroom.

It was a terrible night for Momolo and Marianna: "Both of the policemen stayed in our bedroom, with the guard changing from time to time with others replacing them. You can imagine how we passed that night. Our little son, though he didn't understand what was happening, slept fitfully, shaking with sobs every now and then, with the soldiers at his side."

The only hope left to the family was finding someone in a position to overrule the Inquisitor and vacate his order. There were only two men in Bologna who, in the view of the men of the Mortara and Padovani families, might have such power: the Cardinal Legate, Giuseppe Milesi, and the city's famous but controversial archbishop, Michele Cardinal Viale-Prel?. Encouraged by the diplomatic success enjoyed by Marianna's brother-in-law and uncle the night before at San Domenico, Momolo and Marianna asked them to undertake this new mission. In midmorning, on June 24, they set out.

The Knock at the Door

THE KNOCK CAME at nightfall. It was Wednesday, June 23, 1858. Anna Facchini, a 23-year-old servant, descended a flight of stairs from the Mortara apartment to open the building's outer door. Before her stood a uniformed police officer and a second, middle-aged man of martial bearing.1

"Is this the home of Signor Momolo Mortara?" asked Marshal Lucidi.

Yes, Anna responded, but Signor Mortara was not there. He had gone out with his oldest son.

As the men turned away, she closed the door and returned to the apartment to report the unsettling encounter to her employer, Marianna Mortara. Marianna sat at the living room table, busily stitching, along with her twin 11-year-old daughters, Ernesta and Erminia. Her five younger children, Augusto, aged 10, Arnoldo, 9, Edgardo, 6, Ercole, 4, and Imelda, born just six months before, were already asleep. Marianna, a nervous sort anyway, wished that her husband were home.

A few minutes later, she heard sounds of feet climbing the back stairs, which could be reached through her neighbor's apartment. Marianna stopped her stitching and listened carefully. The knocking on the door confirmed her fears. She approached the door and, without touching it, asked who was there.

"It's the police," a voice said. "Let us in."

Marianna, hoping though not really believing that the policemen had simply made a mistake, told them what she prayed they did not know: they were at the back door of the same apartment they had visited just a few minutes before.

"It doesn't matter, Signora. We are police and we want to come in. Don't worry; we wish you no harm."

Marianna opened the door and let the two men in. She did not notice the rest of the papal police detail, some of whom remained on the nearby stairs while others lingered on the street below.

Pietro Lucidi, marshal in the papal carabinieri and head of the police detail, entered, with Brigadier Giuseppe Agostini, in civilian clothes, following him in. The sight of the military police of the Papal States coming inexplicably in the night filled Marianna with dread.

The Marshal, not at all happy about the mission before him, and seeing that the woman was already distraught, tried to calm her. Pulling a small sheet of paper from his jacket, he told her he needed to get certain clarifications about her family and asked her to list the names of everyone in the household, beginning with her husband and herself, and proceeding through all her children, from oldest to youngest. Marianna began to shake.

Walking home beneath Bologna's famous porticoes with Riccardo, his 13-year-old son, that pleasant June evening, Momolo was surprised to find police milling around his outside door. He hurried up to his apartment and discovered the police officer and the other strange man talking to his frightened wife.

As Momolo entered the apartment, Marianna exclaimed, "Just listen to what these men want with our family!"

Marshal Lucidi now saw that his worst fears about his mission would be realized, but felt even so a certain relief at now being able to deal with Momolo, who was, after all, a man. Again he stated that he had been given the task of determining just who was in the Mortara household. Momolo, unable to get any explanation for this ominous inquiry, proceeded to name himself, his wife, and each of his eight children.

The Marshal checked all these names on his little list. Having noted all ten members of the family, he announced that he would now like to see each of the children. His request turned Marianna's fright to terror.

Momolo pointed out Riccardo, Ernesta, and Erminia, who had gathered round their parents, but pleaded that his other children were asleep and should be left alone.

Moved, perhaps, but undeterred, the Marshal remained firm. Eventually the Mortaras led the two policemen through the door into their own bedroom, with the three oldest children and the servant trailing them in. There, on a sofa-bed, slept 6-year-old Edgardo. His parents did not yet know that on the list the Marshal had brought with him, Edgardo's name was underlined.

Lucidi told Anna to take the rest of the children out of the room. Once they had left, he turned back to Momolo and said, "Signor Mortara, I am sorry to inform you that you are the victim of betrayal."

"What betrayal?" asked Marianna.

"Your son Edgardo has been baptized," Lucidi responded, "and I have been ordered to take him with me."

Marianna's shrieks echoed through the building, prompting the policemen stationed outside to scurry into the bedroom. The older Mortara children, terrified, sneaked back in as well. Weeping hysterically, Marianna threw herself into Edgardo's bed and clutched the somnolent boy to her.

"If you want my son, you'll have to kill me first!"

"There must be some mistake," Momolo said. "My son was never baptized. . . . Who says Edgardo was baptized? Who says he has to be taken?"

"I am only acting according to orders," pleaded the Marshal. "I'm just following the Inquisitor's orders."

Lucidi despaired as the situation seemed to be slipping out of control. In his own report, he later wrote: "I hardly know how to describe the effect of that fatal announcement. I can assure you that I would have a thousand times preferred to be exposed to much more serious dangers in performing my duties than to have to witness such a painful scene."

With Marianna wailing from Edgardo's bed, Momolo insisting that it was all a horrible mistake, and the children crying, Lucidi scarcely knew what to do. Both parents got down on their knees before the discomfited Marshal, begging him in the name of humanity not to take their child from them. Bending a bit (and no doubt thinking this was all the Inquisitor's fault anyway), Lucidi offered to let Momolo accompany his son to see the Inquisitor at the nearby Convent of San Domenico.

Momolo refused, afraid to let Edgardo into the Inquisitor's hands.

Lucidi recalled: "While I waited for the desperate mother and father, overcome by a terrible agony, to return to reason so that the matter could be brought to its inevitable conclusion, various people began to arrive, either on their own or because they had been called there."

In fact, with Lucidi's permission, Momolo had sent Riccardo to alert Marianna's brother and uncle, and to fetch their elderly Jewish neighbor Bonajuto Sanguinetti, whose wealth and community position, Momolo hoped, might ward off the impending disaster.

Hurrying back to the cafe where, less than an hour before, he and his father had left them, Riccardo came upon his two uncles, Angelo Padovani, his mother's brother, and Angelo Moscato, husband of his mother's sister. Moscato later described the encounter:

"As I sat with my brother-in-law at the Caff? del Genio on via Vetturini, my nephew Riccardo Mortara came running up, in tears and disconsolate, telling me that the carabinieri were in his house, and that they wanted to kidnap his brother Edgardo."

The two men rushed to the Mortaras' apartment: "We saw the mother, devastated, and in such a sorry state that it's impossible to describe. I asked the marshal of the gendarmes to explain what was going on, and he responded that he had an order-though he never showed it to me-from the Inquisitor, Father Pier Gaetano Feletti, to take Edgardo because he had been baptized."

Marianna was "desperate, beside herself," as her brother, Angelo Padovani, recalled. "She lay stretched out on a sofa which they also used as a bed, the sofa on which Edgardo slept, holding him tightly to her chest so that no one could take him."

Trying to find some way to stop the police from making off with Edgardo, Padovani and his brother-in-law persuaded the Marshal not to remove the child before they could consult with their uncle, who lived nearby. The uncle, Marianna's father's brother, whose name was also Angelo Padovani, was still at work in the small bank he ran in the same building in which he lived.

After his nephews filled him in on the dramatic events at the Mortara home, Signor Padovani decided that their only hope was to see the Inquisitor. While the younger Padovani rushed back to inform the Marshal of the need for further delay, the other two men made their way to the convent.

At 11 p.m., they presented themselves at the forbidding gate of San Domenico and asked to be taken to the Inquisitor. Despite the hour, they were rushed up to the Inquisitor's room. They implored Father Feletti to tell them why he had ordered the police to take Edgardo. Responding in measured tones, and hoping to calm them, the Inquisitor explained that Edgardo had been secretly baptized, although by whom, or how he came to know of it, he would not say. Once word of the baptism had reached the proper authorities, they had given him the instructions that he was now carrying out: the boy was a Catholic and could not be raised in a Jewish household.

Padovani protested bitterly. It was an act of great cruelty, he said, to order a child taken from his parents without ever giving them a chance to defend themselves. Father Feletti simply responded that it was not in his power to deviate from the orders he had received. The men begged him to reveal his grounds for thinking that the child had been baptized, for no one in the family knew anything about it. The Inquisitor replied that he could give no such explanation, the matter being confidential, but that they should rest assured that everything had been done properly. It would be best for all concerned, he added, if the members of the family would simply resign themselves to what was to come. "Far from acting lightly in this matter," he told them, "I have acted in good conscience, for everything has been done punctiliously according to the sacred Canons."

Seeing that it was impossible to get Father Feletti to reconsider his order, the men pleaded with him to give the family more time before taking the boy. They asked that he suspend any action for at least a day.

"At first," Moscato later recounted, "that man of stone refused, and we had to paint a picture for him of the sad state of a mother who had another child she was nursing, of a father who was being driven almost out of his mind, and of eight [sic] children clutching at their parents' and the policemen's knees, begging them not to take their brother away from them."

Eventually, the Inquisitor did change his mind and allowed them a twenty-four-hour stay, hoping that in the meantime the distraught mother could be made to leave the apartment, thereby heading off what threatened to become an unfortunate public disturbance. He asked Moscato and Padovani to promise that no attempt would be made to help the boy escape, an assurance they gave only reluctantly.

Father Feletti later recounted what went through his mind as he weighed the risks of permitting the delay. He knew full well, he said, of the "superstitions in which the Jews are steeped," and so he feared not only that "the child might be stolen away," but indeed that he might perhaps even be "sacrificed." His was a belief shared widely in Italy at that time, for it was thought that Jews would rather murder their own children than see them grow up to be Catholic. He would take no chances. In the note he prepared for Padovani to give to Lucidi, he ordered the Marshal to keep Edgardo under constant surveillance.

Meanwhile, the vigil at the Mortara apartment continued as other friends and neighbors converged on the home. Among these was the Mortaras' 71-year-old next-door neighbor, Bonajuto Sanguinetti, like Momolo a transplant from the Jewish community of nearby Reggio Emilia, in the duchy of Modena. Sanguinetti had already gone to bed when Riccardo, after fetching his two uncles at the cafe, came to his home and told the servant what was happening.

Sanguinetti described his first reactions when his servant woke him up: "I went to the window and saw five or six carabinieri walking about under the portico, and at first I was a little confused, thinking that they had come to take one of my own grandchildren."

He rushed to the Mortaras' home: "I saw a distraught mother, bathed in tears, and a father who was tearing out his hair, while the children were down on their knees begging the policemen for mercy. It was a scene so moving I can't begin to describe it. Indeed, I even heard the police marshal, by the name of Lucidi, say that he would have rather been ordered to arrest a hundred criminals than to take that boy away."

At half past midnight, the eerie vigil at the Mortara home was interrupted by the arrival of Moscato and Padovani, brandishing the piece of paper that they had extracted from Father Feletti. Marshal Lucidi was astonished that the Jews had had any success with the Inquisitor. He had assumed that he would not be leaving the apartment that night without the boy.

"I could see," the Marshal later recalled,

that Signor Padovani was an erudite person, of dignified demeanor, a man who was looked up to and respected by his coreligionists, and they counted heavily on him. Indeed, they had good reason to do so, for it must have taken someone of great influence to obtain a stay in the decree, and in my opinion others would not have succeeded in getting one, all the more so when I learned that the order came from the highest level, and that the Father Inquisitor himself was not in a position to change it.

When the Marshal departed, he left a scene that he described as a teatro di pianto e di afflizione, a "theater of tears and affliction." Aside from the ten members of the Mortara family and the two policemen guarding Edgardo, he left behind Marianna's brother, her brother-in-law, her uncle, and two family friends.

Momolo reacted to the news of the stay with relief, saying later it gave them "a ray of hope." He was less happy, though, to discover that in putting into effect the Inquisitor's admonitions to guard Edgardo closely, the Marshal had ordered two of the policemen to remain with the child in the Mortaras' bedroom.

It was a terrible night for Momolo and Marianna: "Both of the policemen stayed in our bedroom, with the guard changing from time to time with others replacing them. You can imagine how we passed that night. Our little son, though he didn't understand what was happening, slept fitfully, shaking with sobs every now and then, with the soldiers at his side."

The only hope left to the family was finding someone in a position to overrule the Inquisitor and vacate his order. There were only two men in Bologna who, in the view of the men of the Mortara and Padovani families, might have such power: the Cardinal Legate, Giuseppe Milesi, and the city's famous but controversial archbishop, Michele Cardinal Viale-Prel?. Encouraged by the diplomatic success enjoyed by Marianna's brother-in-law and uncle the night before at San Domenico, Momolo and Marianna asked them to undertake this new mission. In midmorning, on June 24, they set out.

Descriere

Both moving and informative, this National Book Award Finalist tells the true story of how one boy's kidnapping helped bring about the collapse of the Vatican as a secular power. "A thrilling history".--"Boston Globe.