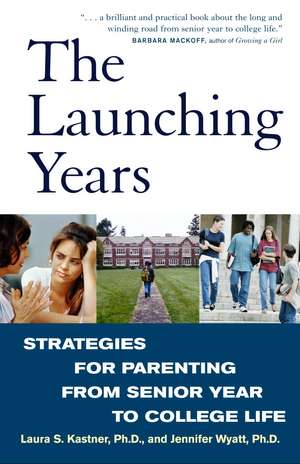

The Launching Years: Strategies for Parenting from Senior Year to College Life

Autor Laura S Kastner, Jennifer Wyatten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

Preț: 95.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 144

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.31€ • 19.58$ • 15.27£

18.31€ • 19.58$ • 15.27£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780609808061

ISBN-10: 0609808060

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: HARMONY

ISBN-10: 0609808060

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: HARMONY

Notă biografică

Laura S. Kastner, Ph.D., is a clinical associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington. She writes and lectures widely on adolescence and family behavior.

Jennifer Wyatt, Ph.D. is a Seattle-based writer who has taught at the college and high school levels.

Jennifer Wyatt, Ph.D. is a Seattle-based writer who has taught at the college and high school levels.

Extras

Chapter One

The Fall Flurry

How to keep the college-application process and planning for the next year from getting out of hand

"Little children disturb your sleep . . . big ones your life." --Proverb

There's an uncanny resemblance between parents-to-be in a childbirthing class and parents at a college-information night, preparing for their high schooler's launch from home. Throughout the challenges of the adolescent years, differences among families are striking?differences in parenting decisions, values, types of children, levels of challenge, life circumstances, and experiences. But like childbirth, the mutual anticipation of change unites parents collectively from various walks of life during launching.

Similar questions weigh on parents' minds: Is my child ready to leave home? If college is the next step, which one? Where will he get in? If not college, what else? Will my child be safe, successful, and happy once he's gone? And more secretly, will I be? What will the quieter house, their perpetually made bed, and the empty place at the dinner table feel like?

Questions proliferate during this unsettling time. Like previous generations, today's parents wonder whether their child can handle the academic demands of college. Can she stay on top of the workload? Does she have enough self-discipline to manage the social whirlwind? Parents acquire a heightened awareness of the thousands of little skills needed for daily living?from remembering to set the alarm in the morning, to meeting crucial deadlines, to making travel arrangements. What will happen once she's on her own?

Control over the purse strings remains a perennial struggle between parents and nearly grown children, and with the cost of education skyrocketing, financial issues feel particularly urgent. Few families are immune from worrying about tuition expenses and whether to saddle their child with debt accrued from college loans. What, parents wonder, should the limits of our monetary support be when our children are not directly under our wing?

Some concerns are specific to our time. Many parents are alarmed by media reports on risks of campus life such as date rape and unprecedented levels of student inebriation. A generation ago, colleges enforced curfews, requiring students to sign in and sign out of dorms, but today's students are virtually free agents. Are the stories we hear about the freedom on today's campus and the lack of adult oversight true? Which young people are potentially binge drinkers or the ones who will eschew relationships for casual sex?

The upsurge in interest in emotional intelligence (strengths related to social and emotional competence) has led parents to wonder whether their soon-exiting children are emotionally mature enough and capable of forming healthy relationships and coping with life's inevitable slings and arrows. Knowing that in one short year they won't be physically present to help their children face difficult problems, parents ask themselves: Does my child have the persistence and initiative to handle responsibilities ahead? What if my son gets depressed after his heart is broken? What if my daughter loses motivation to study when she can't make the grades she got in high school?

The senior year is packed with intense, contradictory emotions and?invariably?increased family friction. With so many launching concerns, parents wonder where to put their energy. Sometimes, we'll feel confident, joyful, and excited in the widening of our children's horizons?and, potentially, ours. Then there are moments when they seem too young to be heading out into this complicated world. What parent doesn't sometimes long to hang on a little tighter, a little longer? The decisions our children are making?their college choices, use of time, evolving values, and relationships?carry significant life consequences, so parents hope to make their influence felt. We have our preconceptions, dreams, and expectations for our children, which rarely match theirs 100 percent, potentially creating more family fray.

Significant parental soul searching takes place senior year. Have I done a good job? What might I have done differently in my child-rearing? How can I continue to have a close relationship with my child after launching? What's next in my life when parenting is no longer my day-to-day job? Despite the reflective mood of senior year?which is natural and necessary because it helps parents prepare for their child's leave-taking?parents still need to remain attentive to their senior's needs in the present. And those needs are often considerable. Right as seniors are planning their exits, parents are often surprised by being pulled closely into their seniors' lives, whether it's through their child's unexpected clinginess and dependency or increased risk-taking.

Whether described as "emerging adults" or "late adolescents" (some developmental psychologists lump these years into adolescence itself), 18 year olds in our culture straddle the worlds of childhood and adulthood and are not fully self-sufficient. Most will spend the next several years setting their direction and acquiring the necessary competencies to be on their own. During this stage?and particularly during senior year and the first year post?high school?parents play a crucial role in moving their children toward increased independence. Ideally, this occurs in a context of support and close relationships; research shows that late adolescents who describe their parents as "available" have greater resilience.1 Even when our children are living elsewhere, we can continue to nurture their development. The fall of senior year, however, many families are focusing on applying to college, trying to decide whether to apply early (a controversial trend), or, in some cases, determining other options.

"Jelling" into College

My best advice for parents of college-bound seniors is this: Beware of the feeding frenzy around college ratings, and do whatever it takes to keep the college-application process calm and contained so that it doesn't engulf what's likely to be your last year with your child at home. Though they may not show it, most seniors worry about leaving home at least as much as their parents do. Relatives, neighbors, and strangers on airplanes make conversation with high-school seniors by asking them where they're applying to college. In this year of feeling sized-up and judged, seniors need cool-headed, supportive parents, not ones who add to the pressure cooker. The best hand we can lend our seniors during the application process is to provide emotional ballast for their anxiety, controlling our own and maintaining perspective.

That said, where does a family start in the college selection process? One useful exercise for parents is to pull out their child's school records to review messages teachers have been sending about their child as a student. How motivated is she? Where do interests lie? What are strengths and weaknesses? Your child's record will tell you what's reasonable to expect. Although young people may change?many late bloomers catch on fire later?parents have noticed over time whether their child takes a lot of prodding to buckle down to schoolwork or is the focused, goal-setting type.

College counselors and admissions officers tell families to seek "the best fit." That's terrific advice, since too many families fixate only on "the best school." Parents who set their minds on finding the school that matches their child are savvy consumers of higher education, since the value of an education depends on individual effectiveness rather than intrinsic worth.

Think of the college decision as an identity decision. Throughout adolescence, young people are slowly forming and "jelling," a process shaping who they are, the experiences they pursue, the values they embrace, the aptitudes they build on, and where their passions lie?what they'll stay up after midnight to complete and what leaves them cold. The decision of what to do after high school should be an outgrowth of their solidifying identity. A high-school senior is a sum total of 18 years of development. If there are disappointments, academic patterns, or features that make parents concerned about a successful launch, anxiety will undoubtedly escalate around college-application time.

High-achieving parents who have been chronically dissatisfied with their child's B's and C's can be distressed over what they see as limited options. When their seniors have less than stellar GPA's, parents can feel like they're on the edge of the diving board over uncertain waters, but in actuality, there are great matches in higher education for different student profiles. With over 3,000 accredited colleges in the United States, nearly every high-school graduate can be accepted into a college. Over 1,000 colleges admit students with C averages, and B students can attend all but the 200 most selective institutions.2

Pressure mounting, parents can get worked up over the quirkiness of college admission, a particular danger when parents over-identify with their child. As acceptance becomes increasingly more competitive, it's every parent's worst nightmare to think that their deserving child might be rejected from the school his heart is set on attending. Playing the college financial-aid game creates additional uncertainties. With students experiencing the pinched acceptance rate of top colleges, parents are having their own parallel version of the desperate feelings seniors often experience during this time.

Parents whose children are driven to excel are often genetically wired for ambition themselves, which can interfere with the kind of calm, emotional support and reassurance that help seniors most. When everyone in the family is hardwired to "go for it," parents may need to put a check on their own drives so they can stay composed as their senior flips out.

Launching a child to college can feel as if it's one of our last hands-on parenting acts. The college choice appears to be our child's link to the future, and, hoping to control as much as we can, we want it to be the best possible link. Invested in our child's future, we start to view college choice as the key to everything we want for our child, when in fact, no set of empirical data has been able to establish that where a young person attends college automatically correlates with success. What does correlate with eventual occupational success is the number of years of higher education; it matters that young people finish their degrees, but the specific college has no statistical significance, nor, interestingly enough, do grades in high school or college.3

Wise parents adopt a broader framework. Instead of asking, "where will my child go to college?" as the benchmark of success, look to questions that truly are vital to one's future, such as these:

* Is my child building strong interests and pursuing them both inside and outside school?

* Does he seem motivated to do well, wherever he goes?

* Does he know how to take full advantage of whatever resources a college has?

* Is he engaged, aware, resilient, responsible, and committed to living a productive life?

* Is my child developing a life based on worthy values and goals?

Since our parenting goal is the development of a well-adjusted adult, not just college admission, parents may need to monitor their reactions and remind themselves: There are many paths children can take to be happy and successful. Any room full of accomplished adults is likely to contain more people who graduated from mid-ranking colleges than from top-tier schools.

Only too easily does the tail start to wag the dog, and college choice begins to influence what a teen does?all for the sake of the college application. Parents of seniors can direct too much energy away from child-rearing, project into the future, and lose track of all of the developmental tasks of an 18 year old. During this culminating year, there's usually ample room for growth in areas like building character, making ethical decisions, or developing healthy habits.

To make it a good senior year, keep up your parenting, look beyond college rankings, and find the school that realistically matches the gifts and passions of your child. Then make a leap of faith that where he ends up is probably the best place. A healthy motto for parents is this: Whatever school rejects my child doesn't deserve him!

The Fall Flurry

How to keep the college-application process and planning for the next year from getting out of hand

"Little children disturb your sleep . . . big ones your life." --Proverb

There's an uncanny resemblance between parents-to-be in a childbirthing class and parents at a college-information night, preparing for their high schooler's launch from home. Throughout the challenges of the adolescent years, differences among families are striking?differences in parenting decisions, values, types of children, levels of challenge, life circumstances, and experiences. But like childbirth, the mutual anticipation of change unites parents collectively from various walks of life during launching.

Similar questions weigh on parents' minds: Is my child ready to leave home? If college is the next step, which one? Where will he get in? If not college, what else? Will my child be safe, successful, and happy once he's gone? And more secretly, will I be? What will the quieter house, their perpetually made bed, and the empty place at the dinner table feel like?

Questions proliferate during this unsettling time. Like previous generations, today's parents wonder whether their child can handle the academic demands of college. Can she stay on top of the workload? Does she have enough self-discipline to manage the social whirlwind? Parents acquire a heightened awareness of the thousands of little skills needed for daily living?from remembering to set the alarm in the morning, to meeting crucial deadlines, to making travel arrangements. What will happen once she's on her own?

Control over the purse strings remains a perennial struggle between parents and nearly grown children, and with the cost of education skyrocketing, financial issues feel particularly urgent. Few families are immune from worrying about tuition expenses and whether to saddle their child with debt accrued from college loans. What, parents wonder, should the limits of our monetary support be when our children are not directly under our wing?

Some concerns are specific to our time. Many parents are alarmed by media reports on risks of campus life such as date rape and unprecedented levels of student inebriation. A generation ago, colleges enforced curfews, requiring students to sign in and sign out of dorms, but today's students are virtually free agents. Are the stories we hear about the freedom on today's campus and the lack of adult oversight true? Which young people are potentially binge drinkers or the ones who will eschew relationships for casual sex?

The upsurge in interest in emotional intelligence (strengths related to social and emotional competence) has led parents to wonder whether their soon-exiting children are emotionally mature enough and capable of forming healthy relationships and coping with life's inevitable slings and arrows. Knowing that in one short year they won't be physically present to help their children face difficult problems, parents ask themselves: Does my child have the persistence and initiative to handle responsibilities ahead? What if my son gets depressed after his heart is broken? What if my daughter loses motivation to study when she can't make the grades she got in high school?

The senior year is packed with intense, contradictory emotions and?invariably?increased family friction. With so many launching concerns, parents wonder where to put their energy. Sometimes, we'll feel confident, joyful, and excited in the widening of our children's horizons?and, potentially, ours. Then there are moments when they seem too young to be heading out into this complicated world. What parent doesn't sometimes long to hang on a little tighter, a little longer? The decisions our children are making?their college choices, use of time, evolving values, and relationships?carry significant life consequences, so parents hope to make their influence felt. We have our preconceptions, dreams, and expectations for our children, which rarely match theirs 100 percent, potentially creating more family fray.

Significant parental soul searching takes place senior year. Have I done a good job? What might I have done differently in my child-rearing? How can I continue to have a close relationship with my child after launching? What's next in my life when parenting is no longer my day-to-day job? Despite the reflective mood of senior year?which is natural and necessary because it helps parents prepare for their child's leave-taking?parents still need to remain attentive to their senior's needs in the present. And those needs are often considerable. Right as seniors are planning their exits, parents are often surprised by being pulled closely into their seniors' lives, whether it's through their child's unexpected clinginess and dependency or increased risk-taking.

Whether described as "emerging adults" or "late adolescents" (some developmental psychologists lump these years into adolescence itself), 18 year olds in our culture straddle the worlds of childhood and adulthood and are not fully self-sufficient. Most will spend the next several years setting their direction and acquiring the necessary competencies to be on their own. During this stage?and particularly during senior year and the first year post?high school?parents play a crucial role in moving their children toward increased independence. Ideally, this occurs in a context of support and close relationships; research shows that late adolescents who describe their parents as "available" have greater resilience.1 Even when our children are living elsewhere, we can continue to nurture their development. The fall of senior year, however, many families are focusing on applying to college, trying to decide whether to apply early (a controversial trend), or, in some cases, determining other options.

"Jelling" into College

My best advice for parents of college-bound seniors is this: Beware of the feeding frenzy around college ratings, and do whatever it takes to keep the college-application process calm and contained so that it doesn't engulf what's likely to be your last year with your child at home. Though they may not show it, most seniors worry about leaving home at least as much as their parents do. Relatives, neighbors, and strangers on airplanes make conversation with high-school seniors by asking them where they're applying to college. In this year of feeling sized-up and judged, seniors need cool-headed, supportive parents, not ones who add to the pressure cooker. The best hand we can lend our seniors during the application process is to provide emotional ballast for their anxiety, controlling our own and maintaining perspective.

That said, where does a family start in the college selection process? One useful exercise for parents is to pull out their child's school records to review messages teachers have been sending about their child as a student. How motivated is she? Where do interests lie? What are strengths and weaknesses? Your child's record will tell you what's reasonable to expect. Although young people may change?many late bloomers catch on fire later?parents have noticed over time whether their child takes a lot of prodding to buckle down to schoolwork or is the focused, goal-setting type.

College counselors and admissions officers tell families to seek "the best fit." That's terrific advice, since too many families fixate only on "the best school." Parents who set their minds on finding the school that matches their child are savvy consumers of higher education, since the value of an education depends on individual effectiveness rather than intrinsic worth.

Think of the college decision as an identity decision. Throughout adolescence, young people are slowly forming and "jelling," a process shaping who they are, the experiences they pursue, the values they embrace, the aptitudes they build on, and where their passions lie?what they'll stay up after midnight to complete and what leaves them cold. The decision of what to do after high school should be an outgrowth of their solidifying identity. A high-school senior is a sum total of 18 years of development. If there are disappointments, academic patterns, or features that make parents concerned about a successful launch, anxiety will undoubtedly escalate around college-application time.

High-achieving parents who have been chronically dissatisfied with their child's B's and C's can be distressed over what they see as limited options. When their seniors have less than stellar GPA's, parents can feel like they're on the edge of the diving board over uncertain waters, but in actuality, there are great matches in higher education for different student profiles. With over 3,000 accredited colleges in the United States, nearly every high-school graduate can be accepted into a college. Over 1,000 colleges admit students with C averages, and B students can attend all but the 200 most selective institutions.2

Pressure mounting, parents can get worked up over the quirkiness of college admission, a particular danger when parents over-identify with their child. As acceptance becomes increasingly more competitive, it's every parent's worst nightmare to think that their deserving child might be rejected from the school his heart is set on attending. Playing the college financial-aid game creates additional uncertainties. With students experiencing the pinched acceptance rate of top colleges, parents are having their own parallel version of the desperate feelings seniors often experience during this time.

Parents whose children are driven to excel are often genetically wired for ambition themselves, which can interfere with the kind of calm, emotional support and reassurance that help seniors most. When everyone in the family is hardwired to "go for it," parents may need to put a check on their own drives so they can stay composed as their senior flips out.

Launching a child to college can feel as if it's one of our last hands-on parenting acts. The college choice appears to be our child's link to the future, and, hoping to control as much as we can, we want it to be the best possible link. Invested in our child's future, we start to view college choice as the key to everything we want for our child, when in fact, no set of empirical data has been able to establish that where a young person attends college automatically correlates with success. What does correlate with eventual occupational success is the number of years of higher education; it matters that young people finish their degrees, but the specific college has no statistical significance, nor, interestingly enough, do grades in high school or college.3

Wise parents adopt a broader framework. Instead of asking, "where will my child go to college?" as the benchmark of success, look to questions that truly are vital to one's future, such as these:

* Is my child building strong interests and pursuing them both inside and outside school?

* Does he seem motivated to do well, wherever he goes?

* Does he know how to take full advantage of whatever resources a college has?

* Is he engaged, aware, resilient, responsible, and committed to living a productive life?

* Is my child developing a life based on worthy values and goals?

Since our parenting goal is the development of a well-adjusted adult, not just college admission, parents may need to monitor their reactions and remind themselves: There are many paths children can take to be happy and successful. Any room full of accomplished adults is likely to contain more people who graduated from mid-ranking colleges than from top-tier schools.

Only too easily does the tail start to wag the dog, and college choice begins to influence what a teen does?all for the sake of the college application. Parents of seniors can direct too much energy away from child-rearing, project into the future, and lose track of all of the developmental tasks of an 18 year old. During this culminating year, there's usually ample room for growth in areas like building character, making ethical decisions, or developing healthy habits.

To make it a good senior year, keep up your parenting, look beyond college rankings, and find the school that realistically matches the gifts and passions of your child. Then make a leap of faith that where he ends up is probably the best place. A healthy motto for parents is this: Whatever school rejects my child doesn't deserve him!

Descriere

This guide for parents of teens making the transition from high school to college suggests detailed, practical ways to weather the emotional onslaught of impending separation. From parents experiencing "empty-nest blues" to helping teens avoid the slump of "senioritis, " the authors offer down-to-earth advice to get through this challenging time.