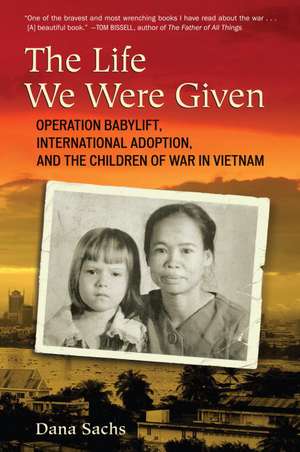

The Life We Were Given: Operation Babylift, International Adoption, and the Children of War in Vietnam

Autor Dana Sachsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2011

Often presented as a great humanitarian effort, Operation Babylift provided an opportunity for national catharsis following the trauma of the American experience in Vietnam. Now, thirty-five years after the war ended, Dana Sachs examines this unprecedented event more carefully, revealing how a single public-policy gesture irrevocably altered thousands of lives, not always for the better. Though most of the children were orphans, many were not, and the rescue offered no possibility for families to later reunite.

With sensitivity and balance, Sachs deepens her account by including multiple perspectives: birth mothers making the wrenching decision to relinquish their children; orphanage workers, military personnel, and doctors trying to "save" them; politicians and judges attempting to untangle the controversies; adoptive families waiting anxiously for their new sons and daughters; and the children themselves, struggling to understand. In particular, the book follows one such child, Anh Hansen, who left Vietnam through Operation Babylift and, decades later, returned to reunite with her birth mother. Through Anh's story, and those of many others, The Life We Were Given will inspire impassioned discussion and spur dialogue on the human cost of war, international adoption and aid efforts, and U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 165.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 248

Preț estimativ în valută:

31.59€ • 33.07$ • 26.14£

31.59€ • 33.07$ • 26.14£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 05-19 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807001240

ISBN-10: 0807001244

Pagini: 258

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807001244

Pagini: 258

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Notă biografică

Dana Sachs has written about Vietnam for twenty years. The author of The House on Dream Street: Memoir of an American Woman in Vietnam and the novel If You Lived Here, and coauthor of Two Cakes Fit for a King: Folktales from Vietnam, she teaches at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington and lives in North Carolina.

Recenzii

Deeply compelling and deftly researched, Dana Sachs's The Life We Were Given vividly documents this controversial mass evacuation while trailing the heartbreaking narratives of the children-from village life to orphanage to hastily arranged flights to the United States and into the homes of waiting American adoptive parents. The Life We Were Given is a powerful exploration of the questions that haunt everyone involved in adoption.—Meredith Hall, author of Without A Map

"The saddest story in the whole awful sweep of the war in Vietnam had nothing to do with soldiers or ideology and has never been fully told—possibly because no one could bear to. Thankfully, Dana Sachs fills that void with The Life We Were Given, one of the bravest and most wrenching books I have read about the war. All the victims and heroes of the Orphan Airlift come unforgettably to life in this beautiful book, and I will not soon forget them, or it."—Tom Bissell, author of The Father of All Things

"The Life We Were Given</i< is a work of great compassion and scope that gives voice to the tragedy and salvation of thousands of Vietnamese orphans. Dana Sachs has compiled an impressive collection of personal stories and presented them with concise historical background to give this subject the depth it so rightly deserves. An illuminating book worth reading."—Andrew X. Pham, author of Catfish and Mandala and The Eaves of Heaven

"With its clear and compelling truths about war, children, fear, and hope, The Life We Were Given becomes one of our very best and most important books about America's involvement with the people of Vietnam. And it's so much more. Exquisitely written, full of breathtaking suspense, this book will become a classic, a must-read."—Clyde Edgerton, author of Lunch at the Piccadilly and The Bible Salesman

"This gripping account of Operation Babylift allows the voices of those directly affected by the experience to speak out. . . . Unmatched in its breadth of perspective and depth of insight . . . Sachs has broken new ground in our continued understanding and insight into how powerful Operation Babylift was on our national consciousness and the many lives it impacted."—Bert Ballard, PhD, Operation Babylift adoptee (April 1975), international adoption researcher, adoptee activist

From the Hardcover edition.

"The saddest story in the whole awful sweep of the war in Vietnam had nothing to do with soldiers or ideology and has never been fully told—possibly because no one could bear to. Thankfully, Dana Sachs fills that void with The Life We Were Given, one of the bravest and most wrenching books I have read about the war. All the victims and heroes of the Orphan Airlift come unforgettably to life in this beautiful book, and I will not soon forget them, or it."—Tom Bissell, author of The Father of All Things

"The Life We Were Given</i< is a work of great compassion and scope that gives voice to the tragedy and salvation of thousands of Vietnamese orphans. Dana Sachs has compiled an impressive collection of personal stories and presented them with concise historical background to give this subject the depth it so rightly deserves. An illuminating book worth reading."—Andrew X. Pham, author of Catfish and Mandala and The Eaves of Heaven

"With its clear and compelling truths about war, children, fear, and hope, The Life We Were Given becomes one of our very best and most important books about America's involvement with the people of Vietnam. And it's so much more. Exquisitely written, full of breathtaking suspense, this book will become a classic, a must-read."—Clyde Edgerton, author of Lunch at the Piccadilly and The Bible Salesman

"This gripping account of Operation Babylift allows the voices of those directly affected by the experience to speak out. . . . Unmatched in its breadth of perspective and depth of insight . . . Sachs has broken new ground in our continued understanding and insight into how powerful Operation Babylift was on our national consciousness and the many lives it impacted."—Bert Ballard, PhD, Operation Babylift adoptee (April 1975), international adoption researcher, adoptee activist

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Introduction

The photograph shows a row of red-and-yellow striped seats inside the

cabin of an airplane. They look like any seats on any commercial jetliner,

though the mod color scheme does help date them to the 1970s.

What is odd about the photograph is not the seats themselves, but who

occupies them: on each seat lies a tiny baby swaddled in white pajamas.

As human beings, we view babies as vulnerable, and a solitary infant, in

any context, seems strange and pathetic. These particular children look

like dolls that some prankish three-year-old left forgotten on the sofa.

A few of these children appear to be sleeping. One faces the camera,

looking both curious and forlorn.

I first came across this picture in the spring of 2004, while reading

about Vietnam on the Internet. I had been writing about the country

for many years, but I had never seen the photograph or heard about

the event it depicted. Now, on the Web site, I discovered that in April

1975, at the very end of the war in Vietnam, a group of foreign-run orphanages,

with the help of the U.S. government, airlifted between two

thousand and three thousand children out of Saigon and placed them

with adoptive families overseas. The Web site showed photos from only

one jet, but I learned that there had been many babies, and some four

dozen flights that carried them out of Vietnam.

As a writer, my interest in Vietnam had, until that moment, consciously

focused on the country as a country, not as a participant in a

war. Too much attention had centered on the conflicts of the twentieth

century and as a result, I believed, Americans knew little about the place

except that we had fought a devastating war there. Now, looking at

this puzzling photograph of babies on an airplane, I reminded myself

that every war produces its own set of bizarre situations. Apparently,

Operation Babylift had been one such situation that emerged from the

war in Vietnam. I moved along in my research and told myself to forget

about it.

I couldn’t get my mind off those babies, though. April 1975 marked

the end of the war in Southeast Asia, the moment that, after three decades

of conflict, Vietnam finally emerged into a time of peace. Right at

that moment, however, thousands of children were airlifted away from

their homeland. Why? It didn’t make sense to me. Months passed. Every

so often, I’d make my way back to the computer, just to have another

look. Each time, the same questions filtered through my mind: Who

were these children? How did they end up on those planes?

Orphans play a peculiar role in our consciousness. The idea of a child

without parents defies the natural order, evoking a pity so deep it feels

instinctive, like some remnant of our pre-conscious past. Perhaps it’s the

pathos of the image that explains why so many myths and legends include

children raised by wolves, or floating down rivers in woven baskets,

or wandering lost through haunted woods. Our desire to help such

children takes on a meaning that goes well beyond the individuals themselves.

By saving them, we’re saving ourselves and saving our species.

And yet, we have always treated children badly, too. Throughout

history, children have borne the brunt of war, and illness, and poverty.

Nearly three thousand years ago, the Spartans created a brutal army

of ruthless young men by forcing little boys to survive in the streets.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, young boys served as

“powder monkeys,” carrying explosives to gunners on board ships. Even

in times of peace, children have filled out the ranks of farm workers

and laborers throughout the world. It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth

century, around the time that Charles Dickens introduced both Pip and

Oliver Twist, that society began actively addressing the gap between

our expectations of how we should treat children and the reality of their

suffering. In 1851, the Massachusetts legislature introduced the Adoption

of Children Act, the first legal mandate requiring that adoption

decisions promote the welfare of the child, not the desires of adults.

Over the next few decades, American society came to regard adoption

as a viable means of ensuring the well-being of children who had no

families to care for them.

By the twentieth century, this commitment to our own orphans expanded

to include helping foreign children made vulnerable by war.

After the Holocaust, the U.S. government accepted as immigrants

thousands of displaced children. Though the attempts were haphazard

and often unsuccessful, some effort was made to find these children’s

families before placing them for adoption. Following Fidel Castro’s

revolution in Cuba, a program known as “Operation Pedro Pan” evacuated

thousands of Cuban children, in small groups and on commercial

flights, to the United States, where many were reunited with relatives.

In 1970, two years after the end of the Nigerian civil war, five thousand

Biafran children, who had been evacuated from the country for their

safety, returned to their families and villages. “It’s not your fault that you

left your country,” Nigeria’s head of state told one group of children

as they arrived, adding, “We’re very, very happy to see you back here

with us.”

Operation Babylift followed what had, by then, become a familiar

pattern: war creates orphans, and then civilized society steps in to help.

If the war itself revealed our basest nature, then humanitarian interventions

unveiled our best—a deeply felt desire to save the lives of defenseless

kids. As an April 1975 article in Time magazine described Operation

Babylift, which was taking place at the time, “Not since the return of the

prisoners of war two years ago [has] there been a news story out of Viet

Nam with which the average American could so readily identify, one

in which individuals seemed able to atone, even in the most tentative

way, for the collective sins of governments.” It was a feel-good effort,

to be sure, but the Babylift also marked a new phase of humanitarian

endeavor, and it revealed a new philosophy with regard to what it means

to “save” a child. Earlier efforts had centered on reuniting families torn

apart by war; adoption was a backup plan. In contrast, this mission

focused completely on adoption. Evacuation organizers claimed that

these children were orphans. It quickly became clear, however, that a

significant number were being put into permanent homes without clear

proof of their eligibility for adoption. Some children, it seemed, came

from Vietnam’s most vulnerable families, and they had been swept up

in the panic of those last days of war and transported to new, permanent

homes overseas.

Eventually, I stopped trying to ignore the story of Operation Babylift.

For the past six years, I have tried, instead, to unravel the tangle

of events that led, in April 1975, to the mass evacuation of those children

from Vietnam, approximately 80 percent of whom ended up in

the United States, while the rest were adopted by families in Canada,

Australia, and Europe. Even as the airlift was taking place, controversy

began to swirl over whether it was an appropriate response to the crisis

facing these children. The arguments focused on many factors—the

oversight of the mission, the family status of the children involved,

the appalling conditions of children in wartime South Vietnam—but

these debates also coalesced around a single vexing question about

adoption itself: is the primary purpose of adoption to find a home for

an orphan or to satisfy the needs of a family that wants a child? That

question, of course, remains, to this day, at the center of the controversy

over international adoption.

The photograph shows a row of red-and-yellow striped seats inside the

cabin of an airplane. They look like any seats on any commercial jetliner,

though the mod color scheme does help date them to the 1970s.

What is odd about the photograph is not the seats themselves, but who

occupies them: on each seat lies a tiny baby swaddled in white pajamas.

As human beings, we view babies as vulnerable, and a solitary infant, in

any context, seems strange and pathetic. These particular children look

like dolls that some prankish three-year-old left forgotten on the sofa.

A few of these children appear to be sleeping. One faces the camera,

looking both curious and forlorn.

I first came across this picture in the spring of 2004, while reading

about Vietnam on the Internet. I had been writing about the country

for many years, but I had never seen the photograph or heard about

the event it depicted. Now, on the Web site, I discovered that in April

1975, at the very end of the war in Vietnam, a group of foreign-run orphanages,

with the help of the U.S. government, airlifted between two

thousand and three thousand children out of Saigon and placed them

with adoptive families overseas. The Web site showed photos from only

one jet, but I learned that there had been many babies, and some four

dozen flights that carried them out of Vietnam.

As a writer, my interest in Vietnam had, until that moment, consciously

focused on the country as a country, not as a participant in a

war. Too much attention had centered on the conflicts of the twentieth

century and as a result, I believed, Americans knew little about the place

except that we had fought a devastating war there. Now, looking at

this puzzling photograph of babies on an airplane, I reminded myself

that every war produces its own set of bizarre situations. Apparently,

Operation Babylift had been one such situation that emerged from the

war in Vietnam. I moved along in my research and told myself to forget

about it.

I couldn’t get my mind off those babies, though. April 1975 marked

the end of the war in Southeast Asia, the moment that, after three decades

of conflict, Vietnam finally emerged into a time of peace. Right at

that moment, however, thousands of children were airlifted away from

their homeland. Why? It didn’t make sense to me. Months passed. Every

so often, I’d make my way back to the computer, just to have another

look. Each time, the same questions filtered through my mind: Who

were these children? How did they end up on those planes?

Orphans play a peculiar role in our consciousness. The idea of a child

without parents defies the natural order, evoking a pity so deep it feels

instinctive, like some remnant of our pre-conscious past. Perhaps it’s the

pathos of the image that explains why so many myths and legends include

children raised by wolves, or floating down rivers in woven baskets,

or wandering lost through haunted woods. Our desire to help such

children takes on a meaning that goes well beyond the individuals themselves.

By saving them, we’re saving ourselves and saving our species.

And yet, we have always treated children badly, too. Throughout

history, children have borne the brunt of war, and illness, and poverty.

Nearly three thousand years ago, the Spartans created a brutal army

of ruthless young men by forcing little boys to survive in the streets.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, young boys served as

“powder monkeys,” carrying explosives to gunners on board ships. Even

in times of peace, children have filled out the ranks of farm workers

and laborers throughout the world. It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth

century, around the time that Charles Dickens introduced both Pip and

Oliver Twist, that society began actively addressing the gap between

our expectations of how we should treat children and the reality of their

suffering. In 1851, the Massachusetts legislature introduced the Adoption

of Children Act, the first legal mandate requiring that adoption

decisions promote the welfare of the child, not the desires of adults.

Over the next few decades, American society came to regard adoption

as a viable means of ensuring the well-being of children who had no

families to care for them.

By the twentieth century, this commitment to our own orphans expanded

to include helping foreign children made vulnerable by war.

After the Holocaust, the U.S. government accepted as immigrants

thousands of displaced children. Though the attempts were haphazard

and often unsuccessful, some effort was made to find these children’s

families before placing them for adoption. Following Fidel Castro’s

revolution in Cuba, a program known as “Operation Pedro Pan” evacuated

thousands of Cuban children, in small groups and on commercial

flights, to the United States, where many were reunited with relatives.

In 1970, two years after the end of the Nigerian civil war, five thousand

Biafran children, who had been evacuated from the country for their

safety, returned to their families and villages. “It’s not your fault that you

left your country,” Nigeria’s head of state told one group of children

as they arrived, adding, “We’re very, very happy to see you back here

with us.”

Operation Babylift followed what had, by then, become a familiar

pattern: war creates orphans, and then civilized society steps in to help.

If the war itself revealed our basest nature, then humanitarian interventions

unveiled our best—a deeply felt desire to save the lives of defenseless

kids. As an April 1975 article in Time magazine described Operation

Babylift, which was taking place at the time, “Not since the return of the

prisoners of war two years ago [has] there been a news story out of Viet

Nam with which the average American could so readily identify, one

in which individuals seemed able to atone, even in the most tentative

way, for the collective sins of governments.” It was a feel-good effort,

to be sure, but the Babylift also marked a new phase of humanitarian

endeavor, and it revealed a new philosophy with regard to what it means

to “save” a child. Earlier efforts had centered on reuniting families torn

apart by war; adoption was a backup plan. In contrast, this mission

focused completely on adoption. Evacuation organizers claimed that

these children were orphans. It quickly became clear, however, that a

significant number were being put into permanent homes without clear

proof of their eligibility for adoption. Some children, it seemed, came

from Vietnam’s most vulnerable families, and they had been swept up

in the panic of those last days of war and transported to new, permanent

homes overseas.

Eventually, I stopped trying to ignore the story of Operation Babylift.

For the past six years, I have tried, instead, to unravel the tangle

of events that led, in April 1975, to the mass evacuation of those children

from Vietnam, approximately 80 percent of whom ended up in

the United States, while the rest were adopted by families in Canada,

Australia, and Europe. Even as the airlift was taking place, controversy

began to swirl over whether it was an appropriate response to the crisis

facing these children. The arguments focused on many factors—the

oversight of the mission, the family status of the children involved,

the appalling conditions of children in wartime South Vietnam—but

these debates also coalesced around a single vexing question about

adoption itself: is the primary purpose of adoption to find a home for

an orphan or to satisfy the needs of a family that wants a child? That

question, of course, remains, to this day, at the center of the controversy

over international adoption.