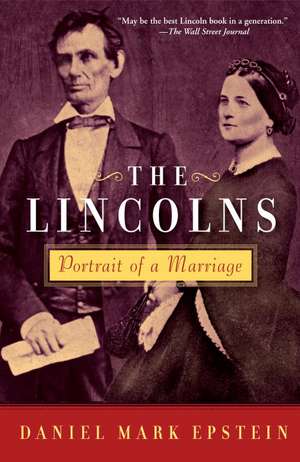

The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage

Autor Daniel Mark Epsteinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2008

The first full-length portrait of the marriage of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln in more than fifty years, The Lincolns is written with enormous sweep and striking imagery. Daniel Mark Epstein makes two immortal American figures seem as real and human as the rest of us.

Preț: 150.52 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 226

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.81€ • 31.28$ • 24.20£

28.81€ • 31.28$ • 24.20£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345478009

ISBN-10: 0345478002

Pagini: 559

Ilustrații: Photo Insert

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345478002

Pagini: 559

Ilustrații: Photo Insert

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Daniel Mark Epstein is the author of biographies of Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman, Aimee Semple McPherson, Nat King Cole, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, as well as seven volumes of poetry. His verse has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, and The Paris Review, among other publications. The American Academy of Arts and Letters awarded Epstein the Rome Prize in 1977 and an Academy Award in 2006. Daniel Mark Epstein lives in Baltimore.

www.danielmarkepstein.com

From the Hardcover edition.

www.danielmarkepstein.com

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Tryst: Springfield, 1842

Walking east on Jefferson Street with the setting sun behind him, Abraham Lincoln followed his shadow toward the house on Sixth Street where he had arranged to meet his love in secret.

The tall man cast a long shadow in the November light. The October rains and wind had nearly stripped the trees of their leaves—the maple, the walnut, the oak of the prairie. He liked the trees without their foliage “as their anatomy could then be studied.” The outline of a silver maple against the sky was delicate but firm; the network of shades the branches cast upon the ground seemed to him a virtual “profile” of the tree.

“Perhaps a man’s character is like a tree, and his reputation like its shadow; the shadow is what we think of it; the tree is the real thing.” This idea, which would attend the young man on an eventful journey into middle age, might now provide small comfort. For he had gone and made a fool of himself, during the previous two years of his life, a very public sort of fool at the age of thirty-three.

Now, strolling the wooden planks of a makeshift sidewalk laid along the mud ruts of Jefferson Street, past the new state capitol building with its stately columns and dome upon the square, Lincoln followed his shadow and his reputation toward the home of his friend Simeon Francis, where he could pursue his folly behind closed doors. If a man’s character is like the tree and one’s reputation like the shadow, he had begun, by trial and error, to understand his character, his virtues and weaknesses; but he still had little sense of what the world might make of his reputation.

He was a secretive man, who kept his own counsel. He was an ambitious man of humble origins, with colossal designs on the future. And it would always be advantageous not to be closely known, never to be transparent. Passing a farmer on a dray, he would tip his hat and grin. Everybody knew him. Nobody knew him. He would play the fool, the clown, the melancholy poet dying for love, the bumpkin. He would take the world by stealth and not by storm. He would disarm enemies by his apparent naïveté, by seeming pleasantly harmless. He would go to such lengths in making fun of his own appearance that others felt obliged to defend it.

On this November afternoon in 1842 it would hardly seem necessary to argue that he was appealing to women, this lanky, clean-shaven fellow, seeing as how one of the most attractive, nubile ladies of Springfield had singled him out, pursued him, and was now waiting for him in the parlor of that house on the northeast corner of Jefferson and Sixth streets.

The friend who owned the house, Simeon Francis, editor of the Sangamo Journal, and his wife, Eliza, were childless. They made their large home available for Lincoln and his beloved as a trysting place, where they had been meeting since the summer. The inhibitions that attend lovers when they first are alone, speechless, had gradually given way until they found themselves in a situation where marriage was, if not obligatory, inevitable.

Lincoln knew he had made a spectacle of himself on a grand scale recently, in the newspapers, caught up in a scandalous duel—there were rumors the cause of it was Miss Mary Todd. And now walking on his way to what might be greater imprudence, he could reflect that only a few years earlier he had resolved never again to get into such a scrape.

In 1838, on April Fool’s Day, he had written a letter to Eliza Browning, wife of his lawyer friend Orville Hickman Browning, in which he had reached the following conclusion: “Others have been made fools of by the girls; but this can never be with truth said of me. I most emphatically, in this instance, made a fool of myself. I have now come to the conclusion never again to think of marrying; and for this reason; I can never be satisfied with any one who would be block-head enough to have me.” Perhaps he was only joking. He had more masks and poses than Hamlet. This letter explaining his failed courtship of the tall, matronly Miss Owens is scathing comedy, in which he gives vent to feelings of distaste he could not quite conceal in sardonic billets-doux he wrote to the lady herself.

“Although I had seen her before, she did not look as my immagination [sic] had pictured her. I knew she was oversize, but she now appeared a fair match for Falstaff; I knew she was called an ‘old maid,’ and I felt the truth of at least half of that appellation; but now when I beheld her, I could not for the life avoid thinking of my mother; and this, not from withered features, for her skin was too full of fat, to permit its contracting into wrinkles.” When he had first glimpsed Miss Owens, she had been twenty-four and pretty, but if Lincoln is to be trusted, the years had not been kind. “From her want of teeth, weather-beaten appearance in general, and from a kind of notion that ran in my head, that nothing could have commenced at the size of infancy, and reached her present bulk in less than thirty-five or forty years; and in short, I was not all pleased with her. But what could I do? I had told her sister that I would take her for better or worse.”

The match had been made in a playful spirit, on both sides, at the instigation of Miss Owens’s sister, Mrs. Bennett Able. But after a while no one could be sure just how serious the agreement had become. Lincoln made it a point of honor to keep his word, “especially if others had been induced to act on it,” which in this case he thought they had.

“I was now fairly convinced, that no man on earth would have her, and hence the conclusion that they were bent on holding me to my bargain.” Well, they were not, and he had been mistaken. Miss Mary Owens would marry an excellent husband and have four children—but not Lincoln’s. Knowing his ambivalence, exasperated by his stalling and his convoluted avowals, not of his love but of some deep concern that she might come to grief if he declined to marry her, she relieved him of his suffering by informing him the wedding was not to be.

When he was sure he had heard her correctly, Lincoln was stunned.

“I verry unexpectedly found myself mortified almost beyond endurance. . . . My vanity was deeply wounded by the reflection, that I had so long been too stupid to discover her intentions, and at the same time never doubting that I understood them perfectly; and also, that she whom I had taught myself to believe no body else would have, had actually rejected me with all my fancied greatness; and to cap the whole, I then, for the first time, began to suspect that I was really a little in love with her. But let it go. I’ll try and outlive it.”

That courtship—if one could call it that—had ended. But if he had appeared foolish in his approach to Mary Owens, he made himself look like a lunatic with Mary Todd. He had made a fool of himself not by thinking himself the last chance for a woman he found unattractive, but by falling in love so deeply he lost his wits. He was a romantic figure in a romantic age, regarding himself as a poet and a politician. A follower of Byron and Burns, he had, at thirty, not wholly outgrown his illusions. Who could be more outrageous, more fantastical than an impetuous young man, in love or out, who trusts his heart for guidance rather than his reason?

The first round of his courtship of Mary Todd was played out in public, in 1840. She was a bright-eyed, buxom maiden of twenty-one with glowing skin, abundant auburn hair, and shapely arms and shoulders, which she displayed to the limit the fashion would allow. She was more than a foot shorter than Lincoln, and a friend told her, “You’ll have to take a ladder to get to Abraham’s bosom, Mary,” a remark that made her indignant. He called her Molly. She was widely admired for her beauty and vivacity. “The very creature of excitement,” one man said of her, and “one who could make a bishop forget his prayers,” said another, while even her worst enemy admitted that, until middle age, she remained “a brilliant woman.”

From the day in 1835 when she arrived in Springfield from Kentucky, the fiery seventeen-year-old might have had any bachelor or widower in town, including the charismatic young judge Stephen A. Douglas and the wealthy lawyer Edwin B. Webb, a widower with two children. She might have had the gallant, swashbuckling Irishman James Shields, the state auditor who was destined for military glory. She lived with her sister Elizabeth, the wife of the governor’s son, Ninian Edwards, Jr., in one of the finest houses in Springfield. Yet she chose the tousled Abraham Lincoln in his Conestoga boots. Despite his poverty, his humble origins, her sister’s disapproving frowns—despite his moods and vacillations, his perplexity in love—she had clung to him.

Why? No better answer can be found than in a letter of July 23, 1840, explaining her rejection of one distinguished suitor, “the grandson of Patrick Henry—what an honor!” She wrote: “My hand will never be given, where my heart is not.”

And her heart—as she had confided to several women and at least one suitor—would only go to a man who would someday be president. It was a fairy-tale notion that fused ambition and sentiment. She was as much a romantic in her way as Lincoln was in his, with his idealism, his tormented, melancholy soul, his bittersweet fatalism, and his hunger for glory. In season, Molly wore blossoms—Sangamon phlox, sky-blue asters, wild indigo—prairie flowers invisible to him until he saw them crowning her hair. She danced with him, although he was no good at it; she drew him out in conversation, despite his innate shyness with women. Late in the year 1840 they became engaged.

From the Hardcover edition.

Walking east on Jefferson Street with the setting sun behind him, Abraham Lincoln followed his shadow toward the house on Sixth Street where he had arranged to meet his love in secret.

The tall man cast a long shadow in the November light. The October rains and wind had nearly stripped the trees of their leaves—the maple, the walnut, the oak of the prairie. He liked the trees without their foliage “as their anatomy could then be studied.” The outline of a silver maple against the sky was delicate but firm; the network of shades the branches cast upon the ground seemed to him a virtual “profile” of the tree.

“Perhaps a man’s character is like a tree, and his reputation like its shadow; the shadow is what we think of it; the tree is the real thing.” This idea, which would attend the young man on an eventful journey into middle age, might now provide small comfort. For he had gone and made a fool of himself, during the previous two years of his life, a very public sort of fool at the age of thirty-three.

Now, strolling the wooden planks of a makeshift sidewalk laid along the mud ruts of Jefferson Street, past the new state capitol building with its stately columns and dome upon the square, Lincoln followed his shadow and his reputation toward the home of his friend Simeon Francis, where he could pursue his folly behind closed doors. If a man’s character is like the tree and one’s reputation like the shadow, he had begun, by trial and error, to understand his character, his virtues and weaknesses; but he still had little sense of what the world might make of his reputation.

He was a secretive man, who kept his own counsel. He was an ambitious man of humble origins, with colossal designs on the future. And it would always be advantageous not to be closely known, never to be transparent. Passing a farmer on a dray, he would tip his hat and grin. Everybody knew him. Nobody knew him. He would play the fool, the clown, the melancholy poet dying for love, the bumpkin. He would take the world by stealth and not by storm. He would disarm enemies by his apparent naïveté, by seeming pleasantly harmless. He would go to such lengths in making fun of his own appearance that others felt obliged to defend it.

On this November afternoon in 1842 it would hardly seem necessary to argue that he was appealing to women, this lanky, clean-shaven fellow, seeing as how one of the most attractive, nubile ladies of Springfield had singled him out, pursued him, and was now waiting for him in the parlor of that house on the northeast corner of Jefferson and Sixth streets.

The friend who owned the house, Simeon Francis, editor of the Sangamo Journal, and his wife, Eliza, were childless. They made their large home available for Lincoln and his beloved as a trysting place, where they had been meeting since the summer. The inhibitions that attend lovers when they first are alone, speechless, had gradually given way until they found themselves in a situation where marriage was, if not obligatory, inevitable.

Lincoln knew he had made a spectacle of himself on a grand scale recently, in the newspapers, caught up in a scandalous duel—there were rumors the cause of it was Miss Mary Todd. And now walking on his way to what might be greater imprudence, he could reflect that only a few years earlier he had resolved never again to get into such a scrape.

In 1838, on April Fool’s Day, he had written a letter to Eliza Browning, wife of his lawyer friend Orville Hickman Browning, in which he had reached the following conclusion: “Others have been made fools of by the girls; but this can never be with truth said of me. I most emphatically, in this instance, made a fool of myself. I have now come to the conclusion never again to think of marrying; and for this reason; I can never be satisfied with any one who would be block-head enough to have me.” Perhaps he was only joking. He had more masks and poses than Hamlet. This letter explaining his failed courtship of the tall, matronly Miss Owens is scathing comedy, in which he gives vent to feelings of distaste he could not quite conceal in sardonic billets-doux he wrote to the lady herself.

“Although I had seen her before, she did not look as my immagination [sic] had pictured her. I knew she was oversize, but she now appeared a fair match for Falstaff; I knew she was called an ‘old maid,’ and I felt the truth of at least half of that appellation; but now when I beheld her, I could not for the life avoid thinking of my mother; and this, not from withered features, for her skin was too full of fat, to permit its contracting into wrinkles.” When he had first glimpsed Miss Owens, she had been twenty-four and pretty, but if Lincoln is to be trusted, the years had not been kind. “From her want of teeth, weather-beaten appearance in general, and from a kind of notion that ran in my head, that nothing could have commenced at the size of infancy, and reached her present bulk in less than thirty-five or forty years; and in short, I was not all pleased with her. But what could I do? I had told her sister that I would take her for better or worse.”

The match had been made in a playful spirit, on both sides, at the instigation of Miss Owens’s sister, Mrs. Bennett Able. But after a while no one could be sure just how serious the agreement had become. Lincoln made it a point of honor to keep his word, “especially if others had been induced to act on it,” which in this case he thought they had.

“I was now fairly convinced, that no man on earth would have her, and hence the conclusion that they were bent on holding me to my bargain.” Well, they were not, and he had been mistaken. Miss Mary Owens would marry an excellent husband and have four children—but not Lincoln’s. Knowing his ambivalence, exasperated by his stalling and his convoluted avowals, not of his love but of some deep concern that she might come to grief if he declined to marry her, she relieved him of his suffering by informing him the wedding was not to be.

When he was sure he had heard her correctly, Lincoln was stunned.

“I verry unexpectedly found myself mortified almost beyond endurance. . . . My vanity was deeply wounded by the reflection, that I had so long been too stupid to discover her intentions, and at the same time never doubting that I understood them perfectly; and also, that she whom I had taught myself to believe no body else would have, had actually rejected me with all my fancied greatness; and to cap the whole, I then, for the first time, began to suspect that I was really a little in love with her. But let it go. I’ll try and outlive it.”

That courtship—if one could call it that—had ended. But if he had appeared foolish in his approach to Mary Owens, he made himself look like a lunatic with Mary Todd. He had made a fool of himself not by thinking himself the last chance for a woman he found unattractive, but by falling in love so deeply he lost his wits. He was a romantic figure in a romantic age, regarding himself as a poet and a politician. A follower of Byron and Burns, he had, at thirty, not wholly outgrown his illusions. Who could be more outrageous, more fantastical than an impetuous young man, in love or out, who trusts his heart for guidance rather than his reason?

The first round of his courtship of Mary Todd was played out in public, in 1840. She was a bright-eyed, buxom maiden of twenty-one with glowing skin, abundant auburn hair, and shapely arms and shoulders, which she displayed to the limit the fashion would allow. She was more than a foot shorter than Lincoln, and a friend told her, “You’ll have to take a ladder to get to Abraham’s bosom, Mary,” a remark that made her indignant. He called her Molly. She was widely admired for her beauty and vivacity. “The very creature of excitement,” one man said of her, and “one who could make a bishop forget his prayers,” said another, while even her worst enemy admitted that, until middle age, she remained “a brilliant woman.”

From the day in 1835 when she arrived in Springfield from Kentucky, the fiery seventeen-year-old might have had any bachelor or widower in town, including the charismatic young judge Stephen A. Douglas and the wealthy lawyer Edwin B. Webb, a widower with two children. She might have had the gallant, swashbuckling Irishman James Shields, the state auditor who was destined for military glory. She lived with her sister Elizabeth, the wife of the governor’s son, Ninian Edwards, Jr., in one of the finest houses in Springfield. Yet she chose the tousled Abraham Lincoln in his Conestoga boots. Despite his poverty, his humble origins, her sister’s disapproving frowns—despite his moods and vacillations, his perplexity in love—she had clung to him.

Why? No better answer can be found than in a letter of July 23, 1840, explaining her rejection of one distinguished suitor, “the grandson of Patrick Henry—what an honor!” She wrote: “My hand will never be given, where my heart is not.”

And her heart—as she had confided to several women and at least one suitor—would only go to a man who would someday be president. It was a fairy-tale notion that fused ambition and sentiment. She was as much a romantic in her way as Lincoln was in his, with his idealism, his tormented, melancholy soul, his bittersweet fatalism, and his hunger for glory. In season, Molly wore blossoms—Sangamon phlox, sky-blue asters, wild indigo—prairie flowers invisible to him until he saw them crowning her hair. She danced with him, although he was no good at it; she drew him out in conversation, despite his innate shyness with women. Late in the year 1840 they became engaged.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“With a novelist’s feel for detail and drama, Daniel Mark Epstein portrays the Lincoln marriage with sensitivity and insight, painting an intimate portrait of a complex and consequential marriage. This work is a splendid addition to the Lincoln literature.”

- Doris Kearns Goodwin

“Daniel Mark Epstein’s brilliantly conceived The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage is marked by meticulous scholarship and a balanced evaluation of the union that, until now, has confounded biographers and readers alike. The author, also a poet, has given us an insightful and lyrical narrative of the relationship between Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln that helped make him President.”

- Frank J. Williams, founding Chair of The Lincoln Forum and a member of the U.S. Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission

“Will we ever tire of trying to understand this Man? I doubt it, and in this impressive work, Daniel Mark Epstein approaches Lincoln through his complicated and revealing union with Mary Todd.”

- Ken Burns

“Daniel Epstein in 2004 gave us the best book yet written on Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman. Now he has given us the best book yet written on the marriage of Abraham and Mary Lincoln--a comprehensive, sensitive, elegantly wrought masterpiece that puts us up close and personal with one of the most interesting pairings in American history.”

- John C. Waugh, author of One Man Great Enough: Abraham Lincoln's Road to Civil War

“The Lincolns' marriage has always been shrouded in mystery and sadness. But in this fascinating biography by the peerless Epstein, the ties that bound them together are rendered with tender clarity. Beautifully written, impeccably researched, The Lincolns is destined to join the pantheon of indispensable books on the Civil War. “

- Amanda Foreman, author of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

"Poet, playwright and biographer Epstein presents a history and analysis of the almost operatic marriage of Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln. The vivacious daughter of an aristocratic Kentucky family, Mary let it be known early and not entirely in jest that she intended to marry a man who would become president of the United States. Aggressively wooed by many in her adopted town of Springfield, Ill., she singled out the unlikely Lincoln. Despite a rocky courtship, she married the prairie lawyer with whom she shared a love of poetry, plays, politics and a ferocious ambition. Touching only lightly on their lives before marriage–and not at all on Mary’s decline after her husband’s assassination–Epstein focuses on their turbulent and often unhappy union. Intensely private, secretive and frequently absent, Lincoln was no picnic as a husband; Mary, if anything, was a worse wife. Epstein sensitively charts her descent into what can only be called madness. During the Springfield years her penchant for self-dramatization and self-pity, extreme nervousness, hypersensitivity and bad temper manifested itself in common enough fashion: an unreasoning fear of thunderstorms, grudges held against family and friends, gratuitous insults inflicted and physical assaults on servants and, occasionally, her husband. In the White House her increasingly disordered mind gave way to more serious offenses: lavish, compulsive spending beyond her means, baseless jealousy of other women, tampering with the government payroll and influence peddling. Her inconsolable grief at a second child’s death led to delusions and hallucinations. A seemingly permanent mental instability, perhaps the result of a carriage accident, separated her even further from a husband preoccupied with managing a savage war. She never wavered in her love for or her belief in Lincoln, but Mary appears to have deserved the titles bestowed on her by the president’s aides: the “hellcat” and “Her Satanic Majesty.”

A dynamic picture of a marriage every bit as fractious and as buffeted as the nation the Lincolns served."

– Kirkus Reviews

"[Epstein] is a poet by trade who moonlights in biography, having published lives of Nat King Cole and Aimee Semple McPherson. His account of the Lincolns' marriage combines a poet's sensitivity and imagination with a good historian's rigor and fairness. He has in particular an eye for the shifting tides of status and the tensions they can create: He knows that the wooing of the well-born Mary by the rustic young lawyer Lincoln, no matter how impressive his prospects, entailed a decline in status for her and an advance for him — and a difficult burden for a young marriage to carry.

Mr. Epstein's gift for atmospheric detail cuts deep, too. Death was a constant presence in 19th-century American life, as it seldom is today, and it hovers in the book as it did in the Lincoln's marriage, with the early death of two of their four sons and the slaughter of the Civil War. Yet death could be a link between them. Mr. Epstein describes them visiting a military hospital, moving from cot to cot, "bonded in their compassion, knowing that wounded and dying soldiers lay in hospital beds and on hillsides from here to the horizon, and they could comfort only these few, and for only a little while."… Readers will be grateful for his modesty and for much else. He has written what may be the best Lincoln book in a generation."

-The Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin

“Daniel Mark Epstein’s brilliantly conceived The Lincolns: Portrait of a Marriage is marked by meticulous scholarship and a balanced evaluation of the union that, until now, has confounded biographers and readers alike. The author, also a poet, has given us an insightful and lyrical narrative of the relationship between Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln that helped make him President.”

- Frank J. Williams, founding Chair of The Lincoln Forum and a member of the U.S. Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission

“Will we ever tire of trying to understand this Man? I doubt it, and in this impressive work, Daniel Mark Epstein approaches Lincoln through his complicated and revealing union with Mary Todd.”

- Ken Burns

“Daniel Epstein in 2004 gave us the best book yet written on Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman. Now he has given us the best book yet written on the marriage of Abraham and Mary Lincoln--a comprehensive, sensitive, elegantly wrought masterpiece that puts us up close and personal with one of the most interesting pairings in American history.”

- John C. Waugh, author of One Man Great Enough: Abraham Lincoln's Road to Civil War

“The Lincolns' marriage has always been shrouded in mystery and sadness. But in this fascinating biography by the peerless Epstein, the ties that bound them together are rendered with tender clarity. Beautifully written, impeccably researched, The Lincolns is destined to join the pantheon of indispensable books on the Civil War. “

- Amanda Foreman, author of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

"Poet, playwright and biographer Epstein presents a history and analysis of the almost operatic marriage of Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln. The vivacious daughter of an aristocratic Kentucky family, Mary let it be known early and not entirely in jest that she intended to marry a man who would become president of the United States. Aggressively wooed by many in her adopted town of Springfield, Ill., she singled out the unlikely Lincoln. Despite a rocky courtship, she married the prairie lawyer with whom she shared a love of poetry, plays, politics and a ferocious ambition. Touching only lightly on their lives before marriage–and not at all on Mary’s decline after her husband’s assassination–Epstein focuses on their turbulent and often unhappy union. Intensely private, secretive and frequently absent, Lincoln was no picnic as a husband; Mary, if anything, was a worse wife. Epstein sensitively charts her descent into what can only be called madness. During the Springfield years her penchant for self-dramatization and self-pity, extreme nervousness, hypersensitivity and bad temper manifested itself in common enough fashion: an unreasoning fear of thunderstorms, grudges held against family and friends, gratuitous insults inflicted and physical assaults on servants and, occasionally, her husband. In the White House her increasingly disordered mind gave way to more serious offenses: lavish, compulsive spending beyond her means, baseless jealousy of other women, tampering with the government payroll and influence peddling. Her inconsolable grief at a second child’s death led to delusions and hallucinations. A seemingly permanent mental instability, perhaps the result of a carriage accident, separated her even further from a husband preoccupied with managing a savage war. She never wavered in her love for or her belief in Lincoln, but Mary appears to have deserved the titles bestowed on her by the president’s aides: the “hellcat” and “Her Satanic Majesty.”

A dynamic picture of a marriage every bit as fractious and as buffeted as the nation the Lincolns served."

– Kirkus Reviews

"[Epstein] is a poet by trade who moonlights in biography, having published lives of Nat King Cole and Aimee Semple McPherson. His account of the Lincolns' marriage combines a poet's sensitivity and imagination with a good historian's rigor and fairness. He has in particular an eye for the shifting tides of status and the tensions they can create: He knows that the wooing of the well-born Mary by the rustic young lawyer Lincoln, no matter how impressive his prospects, entailed a decline in status for her and an advance for him — and a difficult burden for a young marriage to carry.

Mr. Epstein's gift for atmospheric detail cuts deep, too. Death was a constant presence in 19th-century American life, as it seldom is today, and it hovers in the book as it did in the Lincoln's marriage, with the early death of two of their four sons and the slaughter of the Civil War. Yet death could be a link between them. Mr. Epstein describes them visiting a military hospital, moving from cot to cot, "bonded in their compassion, knowing that wounded and dying soldiers lay in hospital beds and on hillsides from here to the horizon, and they could comfort only these few, and for only a little while."… Readers will be grateful for his modesty and for much else. He has written what may be the best Lincoln book in a generation."

-The Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.