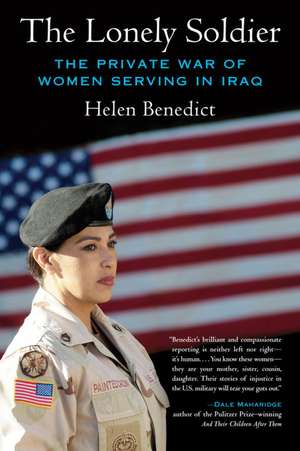

The Lonely Soldier: The Private War of Women Serving in Iraq

Autor Helen Benedicten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2010

More American women have fought and died in Iraq than in any war since World War Two, yet as soldiers they are still painfully alone. In Iraq, only one in ten troops is a woman, and she often serves in a unit with few other women or none at all. This isolation, along with the military's deep-seated hostility toward women, causes problems that many female soldiers find as hard to cope with as war itself: degradation, sexual persecution by their comrades, and loneliness, instead of the camaraderie that every soldier depends on for comfort and survival. As one female soldier said, "I ended up waging my own war against an enemy dressed in the same uniform as mine."

In The Lonely Soldier, Benedict tells the stories of five women who fought in Iraq between 2003 and 2006. She follows them from their childhoods to their enlistments, then takes them through their training, to war and home again, all the while setting the war's events in context.

We meet Jen, white and from a working-class town in the heartland, who still shakes from her wartime traumas; Abbie, who rebelled against a household of liberal Democrats by enlisting in the National Guard; Mickiela, a Mexican American who grew up with a family entangled in L.A. gangs; Terris, an African American mother from D.C. whose childhood was torn by violence; and Eli PaintedCrow, who joined the military to follow Native American tradition and to escape a life of Faulknerian hardship. Between these stories, Benedict weaves those of the forty other Iraq War veterans she interviewed, illuminating the complex issues of war and misogyny, class, race, homophobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Each of these stories is unique, yet collectively they add up to a heartbreaking picture of the sacrifices women soldiers are making for this country.

Benedict ends by showing how these women came to face the truth of war and by offering suggestions for how the military can improve conditions for female soldiers-including distributing women more evenly throughout units and rejecting male recruits with records of violence against women. Humanizing, urgent, and powerful, The Lonely Soldier is a clarion call for change.

Preț: 91.74 lei

Preț vechi: 108.62 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.56€ • 18.14$ • 14.61£

17.56€ • 18.14$ • 14.61£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807061497

ISBN-10: 0807061492

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 150 x 226 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807061492

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 150 x 226 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Notă biografică

Helen Benedict, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, has written frequently on women, race, and justice. Her books include Virgin or Vamp: How the Press Covers Sex Crimes and the novels The Opposite of Love, The Sailor's Wife, Bad Angel, and A World Like This. Her work on soldiers won the James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism.

Recenzii

Benedict's book, filled with compelling and heartbreaking stories, is a groundbreaking testament to the bravery, resilience, and almost insurmountable obstacles faced by women stationed in Iraq.—Deirdre Sinnott, ForeWord

"Whether the soldiers' language is plainspoken or poetic, Helen Benedict's book gives them a place to tell their stories. . . . The Lonely Soldier has strong merit as an account of women's military experience in this long and reckless war."—Amy Herdy, Ms.

"Benedict's brilliant and compassionate reporting is neither left nor right—it's human. . . . You know these women—they are your mother, sister, cousin, daughter. Their stories of injustice in the U.S. military will tear your guts out."—Dale Maharidge, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning And Their Children after Them

"The Lonely Soldier will shock you and enrage you and bring you to tears. It's must reading for everyone who cares about women, justice, fairness, the military, and the United States."—Katha Pollitt, award-winning columnist, The Nation

"A stunning chronicle of abuses suffered by women enlisted in the U.S. Army and serving in Iraq."—Los Angeles Times

"It is hard to determine what is most disturbing about this book—the devious and immoral tactics used by leaders and recruiters to get women to join the military, the terrible poverty and personal violence women were escaping that led them to be vulnerable to such manipulation, the raping and harassing of women soldiers by their superiors and comrades once they got to Iraq, or the untreated homelessness, illnesses, and madness that have haunted [these] women since they came home. . . . A crucial accounting of the shameful war on women who gave their bodies, lives, and souls for their country."—Eve Ensler, playwright, performer, activist, and author of The Vagina Monologues

"Whether the soldiers' language is plainspoken or poetic, Helen Benedict's book gives them a place to tell their stories. . . . The Lonely Soldier has strong merit as an account of women's military experience in this long and reckless war."—Amy Herdy, Ms.

"Benedict's brilliant and compassionate reporting is neither left nor right—it's human. . . . You know these women—they are your mother, sister, cousin, daughter. Their stories of injustice in the U.S. military will tear your guts out."—Dale Maharidge, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning And Their Children after Them

"The Lonely Soldier will shock you and enrage you and bring you to tears. It's must reading for everyone who cares about women, justice, fairness, the military, and the United States."—Katha Pollitt, award-winning columnist, The Nation

"A stunning chronicle of abuses suffered by women enlisted in the U.S. Army and serving in Iraq."—Los Angeles Times

"It is hard to determine what is most disturbing about this book—the devious and immoral tactics used by leaders and recruiters to get women to join the military, the terrible poverty and personal violence women were escaping that led them to be vulnerable to such manipulation, the raping and harassing of women soldiers by their superiors and comrades once they got to Iraq, or the untreated homelessness, illnesses, and madness that have haunted [these] women since they came home. . . . A crucial accounting of the shameful war on women who gave their bodies, lives, and souls for their country."—Eve Ensler, playwright, performer, activist, and author of The Vagina Monologues

Extras

One: The Lonely Soldier

On a blustery night in March 2004, I joined a small crowd in New York

City to honor the citizens and soldiers who had died in the first year of

the Iraq War. Among us were children, Vietnam veterans, and a mother

whose young soldier son had just been killed; she held his wide-eyed

picture up throughout the vigil. Huddling together for warmth, we lit

candles and read aloud the names and ages of the dead. After each

name, a woman struck a huge drum, making a hollow thud that chilled

us more than any cold.

We began with the soldiers: Christian Gurtner, 19. Lori Ann Piestewa,

23. . . .

Once 906 American names had been read, a young man took the

microphone and read the names of some of the many thousands of

Iraqis who had been killed thus far: Valantina Yomas, 2. Falah Hasun,

9 . . . infants and teenagers, mothers and fathers, toddlers and grandmothers

It took at least an hour to read all those names, and afterwards the

young man explained why he knew how to pronounce them: “I’m a

soldier just back from Iraq,” he said, “and we’re being used as cannon

fodder. We’re being sent into war without body armor or decent vehicles

to protect us. And most of the people who are dying in this war are

civilians.”

I was taken aback. This was the first anniversary of the U.S. invasion,

and it was unpopular for anyone to criticize the way the war was

the lonely soldier

being run, let alone someone who had fought in it. Surely this young

soldier was going to be called a traitor by his comrades. So I began to

follow the other few veterans who were speaking out like him, curious

to see what they were up against, which is how I found army specialist

Mickiela Montoya and learned about women at war.

I first saw Mickiela in November 2006, standing silently in the back

of a Manhattan classroom while a group of male veterans spoke to a

small audience. Sentiment had shifted by then, and a poll had just been

released showing that the majority of soldiers were now highly critical

of why and how the war was being fought. Among women serving in

Iraq at the time, 80 percent said they thought the United States should

withdraw within a year, and among men, 69.4 percent agreed.1 Wondering

how this young woman might feel, I approached her. “Are you a

veteran too?” I asked.

“Yes, but nobody believes me.” She tucked her long red hair behind

her ears. “I was in Iraq getting bombed and shot at, but people won’t

even listen when I say I was at war because I’m a female.”

“I’ll listen,” I said. And soon I was listening to all sorts of female

soldiers from all over the country who wanted to tell their stories.

In the end, I interviewed some forty soldiers and veterans for this

book, most of them women. The majority had served in Iraq, but a few

had been deployed to Afghanistan or elsewhere. I included a variety of

ranks, from privates up to a general; all military branches except the

Coast Guard; and soldiers on active duty as well as those in the reserves

and the National Guard. I thus use the word soldier to mean members

of the Marine Corps and air force as well as the army.

Some women had only positive things to say about their service: it

had given them a responsibility they never would have found in civilian

life, and they were proud of what they’d accomplished. This was particularly

true of soldiers in medical units. Captain Claudia Tascon of

the New Jersey National Guard, who immigrated to the United States

from Colombia at age thirteen and served in Iraq from 2004 to 2005,

was one of these. “Because I’m more in the curing business than the

killing business, I’ve seen the good of what we’ve done. We had dentists

and doctors put themselves in harm’s way to help kids in villages. I was

in charge of a warehouse, supplying medical and infantry units all over

northern Iraq, and I was also supplying the Iraqi army, who had nothing

for wounds except saline solution. So I can’t say anything bad about the

the lonely soldier

war.” Then she added, “In the civilian world, you’d never have a twentythree-

year-old in charge of people’s lives and millions of dollars worth

of supplies like I was.”

Marine Corps major Meredith Brown, who comes from New Orleans,

was so proud of her service in Iraq that she said she would go back

in a flash if called, even though she’d had a child since her return. “If I

got killed out there, my son would understand that I’d died to protect

him and other Americans from terrorists coming to our backyard.”

But most of the Iraq War veterans I talked to were much more ambivalent.

Some praised the military but considered the war disastrous,

others found their entire service a nightmare, while yet others fell in

between.

From all these women, I chose to feature five whose stories best

reflected the various experiences of female soldiers in Iraq, although I

have included the stories of others as well. As different as these soldiers

are, they all agreed to be in this book because they wanted to be honest

about what war does to others and what it does to us. Above all, they

wanted people to know what it is like to be a woman at war.

On a blustery night in March 2004, I joined a small crowd in New York

City to honor the citizens and soldiers who had died in the first year of

the Iraq War. Among us were children, Vietnam veterans, and a mother

whose young soldier son had just been killed; she held his wide-eyed

picture up throughout the vigil. Huddling together for warmth, we lit

candles and read aloud the names and ages of the dead. After each

name, a woman struck a huge drum, making a hollow thud that chilled

us more than any cold.

We began with the soldiers: Christian Gurtner, 19. Lori Ann Piestewa,

23. . . .

Once 906 American names had been read, a young man took the

microphone and read the names of some of the many thousands of

Iraqis who had been killed thus far: Valantina Yomas, 2. Falah Hasun,

9 . . . infants and teenagers, mothers and fathers, toddlers and grandmothers

It took at least an hour to read all those names, and afterwards the

young man explained why he knew how to pronounce them: “I’m a

soldier just back from Iraq,” he said, “and we’re being used as cannon

fodder. We’re being sent into war without body armor or decent vehicles

to protect us. And most of the people who are dying in this war are

civilians.”

I was taken aback. This was the first anniversary of the U.S. invasion,

and it was unpopular for anyone to criticize the way the war was

the lonely soldier

being run, let alone someone who had fought in it. Surely this young

soldier was going to be called a traitor by his comrades. So I began to

follow the other few veterans who were speaking out like him, curious

to see what they were up against, which is how I found army specialist

Mickiela Montoya and learned about women at war.

I first saw Mickiela in November 2006, standing silently in the back

of a Manhattan classroom while a group of male veterans spoke to a

small audience. Sentiment had shifted by then, and a poll had just been

released showing that the majority of soldiers were now highly critical

of why and how the war was being fought. Among women serving in

Iraq at the time, 80 percent said they thought the United States should

withdraw within a year, and among men, 69.4 percent agreed.1 Wondering

how this young woman might feel, I approached her. “Are you a

veteran too?” I asked.

“Yes, but nobody believes me.” She tucked her long red hair behind

her ears. “I was in Iraq getting bombed and shot at, but people won’t

even listen when I say I was at war because I’m a female.”

“I’ll listen,” I said. And soon I was listening to all sorts of female

soldiers from all over the country who wanted to tell their stories.

In the end, I interviewed some forty soldiers and veterans for this

book, most of them women. The majority had served in Iraq, but a few

had been deployed to Afghanistan or elsewhere. I included a variety of

ranks, from privates up to a general; all military branches except the

Coast Guard; and soldiers on active duty as well as those in the reserves

and the National Guard. I thus use the word soldier to mean members

of the Marine Corps and air force as well as the army.

Some women had only positive things to say about their service: it

had given them a responsibility they never would have found in civilian

life, and they were proud of what they’d accomplished. This was particularly

true of soldiers in medical units. Captain Claudia Tascon of

the New Jersey National Guard, who immigrated to the United States

from Colombia at age thirteen and served in Iraq from 2004 to 2005,

was one of these. “Because I’m more in the curing business than the

killing business, I’ve seen the good of what we’ve done. We had dentists

and doctors put themselves in harm’s way to help kids in villages. I was

in charge of a warehouse, supplying medical and infantry units all over

northern Iraq, and I was also supplying the Iraqi army, who had nothing

for wounds except saline solution. So I can’t say anything bad about the

the lonely soldier

war.” Then she added, “In the civilian world, you’d never have a twentythree-

year-old in charge of people’s lives and millions of dollars worth

of supplies like I was.”

Marine Corps major Meredith Brown, who comes from New Orleans,

was so proud of her service in Iraq that she said she would go back

in a flash if called, even though she’d had a child since her return. “If I

got killed out there, my son would understand that I’d died to protect

him and other Americans from terrorists coming to our backyard.”

But most of the Iraq War veterans I talked to were much more ambivalent.

Some praised the military but considered the war disastrous,

others found their entire service a nightmare, while yet others fell in

between.

From all these women, I chose to feature five whose stories best

reflected the various experiences of female soldiers in Iraq, although I

have included the stories of others as well. As different as these soldiers

are, they all agreed to be in this book because they wanted to be honest

about what war does to others and what it does to us. Above all, they

wanted people to know what it is like to be a woman at war.

Cuprins

One. The Lonely Soldier

PART ONE

Before

Two. From Girl to Soldier: Life before the Military

Tthree. They Break You Down, Then Build You

Back Up: Mickiela Montoya

Four. They Told Us We Were Going to Be Peacekeepers:

Jennifer Spranger

Five. The Assault Was Just One Bad Person, but It Was a

Turning Point for Me: Abbie Pickett

Six. These Morons Are Going to Get Us Killed:

Terris Dewalt-Johnson

Seven. This War Is Full of Crazy People:

Eli PaintedCrow

PART TWO

War

Eeight. It’s Pretty Much Just You and Your Rifle:

Jennifer Spranger,

Nine. You’re Just Lying There Waiting to See

Who’s Going to Die: Abbie Pickett, ߝ

Ten. You Become Hollow, Like a Robot:

Eli PaintedCrow,

Eleven. I Wasn’t Carrying the Knife for the Enemy,

I Was Carrying It for the Guys on My Own Side:

Mickiela Montoya,

Twelve. Mommy, Love You. Hope You Don’t Get Killed

in Iraq: Terris Dewalt-Johnson, ߝ

PART THREE

After

Thirteen. Coming Home

Fourteen. Fixing the Future

Appendix a. Military Ranks and Organization

Appendix b. Where to Find Help

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

PART ONE

Before

Two. From Girl to Soldier: Life before the Military

Tthree. They Break You Down, Then Build You

Back Up: Mickiela Montoya

Four. They Told Us We Were Going to Be Peacekeepers:

Jennifer Spranger

Five. The Assault Was Just One Bad Person, but It Was a

Turning Point for Me: Abbie Pickett

Six. These Morons Are Going to Get Us Killed:

Terris Dewalt-Johnson

Seven. This War Is Full of Crazy People:

Eli PaintedCrow

PART TWO

War

Eeight. It’s Pretty Much Just You and Your Rifle:

Jennifer Spranger,

Nine. You’re Just Lying There Waiting to See

Who’s Going to Die: Abbie Pickett, ߝ

Ten. You Become Hollow, Like a Robot:

Eli PaintedCrow,

Eleven. I Wasn’t Carrying the Knife for the Enemy,

I Was Carrying It for the Guys on My Own Side:

Mickiela Montoya,

Twelve. Mommy, Love You. Hope You Don’t Get Killed

in Iraq: Terris Dewalt-Johnson, ߝ

PART THREE

After

Thirteen. Coming Home

Fourteen. Fixing the Future

Appendix a. Military Ranks and Organization

Appendix b. Where to Find Help

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Descriere

As a 29-year Army and Army Reserve Colonel, I urge everyone--especially women--to read this important book. Through unforgettable stories, "The Lonely Soldier" explains the shocking frequency of sexual assault and what can be done--Army Reserve Colonel Ann Wright.