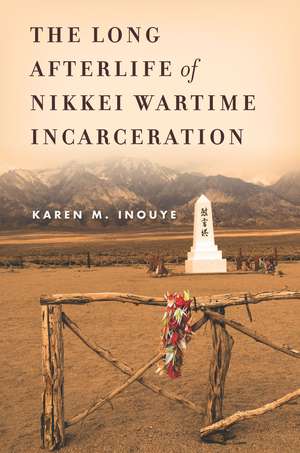

The Long Afterlife of Nikkei Wartime Incarceration: Asian America

Autor Karen Inouyeen Limba Engleză Hardback – 25 oct 2016

While many consider wartime imprisonment an isolated historical moment, Inouye shows how imprisonment and the suspension of rights have continued to impact political discourse and public policies in both the United States and Canada long after their supposed political and legal reversal. In particular, she attends to how activist groups can use the persistence of memory to engage empathetically with people across often profound cultural and political divides. This book addresses the mechanisms by which injustice can transform both its victims and its perpetrators, detailing the dangers of suspending rights during times of crisis as well as the opportunities for more empathetic agency.

Din seria Asian America

-

Preț: 199.10 lei

Preț: 199.10 lei -

Preț: 153.80 lei

Preț: 153.80 lei -

Preț: 227.51 lei

Preț: 227.51 lei -

Preț: 217.51 lei

Preț: 217.51 lei -

Preț: 162.45 lei

Preț: 162.45 lei -

Preț: 132.00 lei

Preț: 132.00 lei -

Preț: 174.55 lei

Preț: 174.55 lei -

Preț: 195.80 lei

Preț: 195.80 lei -

Preț: 156.90 lei

Preț: 156.90 lei -

Preț: 144.88 lei

Preț: 144.88 lei -

Preț: 331.23 lei

Preț: 331.23 lei -

Preț: 220.80 lei

Preț: 220.80 lei -

Preț: 202.61 lei

Preț: 202.61 lei -

Preț: 169.42 lei

Preț: 169.42 lei -

Preț: 159.17 lei

Preț: 159.17 lei -

Preț: 198.66 lei

Preț: 198.66 lei -

Preț: 168.77 lei

Preț: 168.77 lei -

Preț: 231.00 lei

Preț: 231.00 lei -

Preț: 173.51 lei

Preț: 173.51 lei -

Preț: 169.42 lei

Preț: 169.42 lei -

Preț: 155.43 lei

Preț: 155.43 lei -

Preț: 158.35 lei

Preț: 158.35 lei -

Preț: 210.91 lei

Preț: 210.91 lei -

Preț: 310.83 lei

Preț: 310.83 lei -

Preț: 265.55 lei

Preț: 265.55 lei -

Preț: 319.49 lei

Preț: 319.49 lei -

Preț: 444.52 lei

Preț: 444.52 lei -

Preț: 523.65 lei

Preț: 523.65 lei - 19%

Preț: 491.07 lei

Preț: 491.07 lei -

Preț: 477.06 lei

Preț: 477.06 lei -

Preț: 243.76 lei

Preț: 243.76 lei -

Preț: 235.12 lei

Preț: 235.12 lei -

Preț: 304.31 lei

Preț: 304.31 lei - 19%

Preț: 447.25 lei

Preț: 447.25 lei

Preț: 644.44 lei

Preț vechi: 795.60 lei

-19% Nou

123.31€ • 129.09$ • 102.03£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 05-19 aprilie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0804795746

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Stanford University Press

Colecția Stanford University Press

Seria Asian America

Recenzii

Notă biografică

Cuprins

Building on Avery F. Gordon's notion of "haunting," the introduction discusses the moments in which lingering memories of injustice advance to the forefront of consciousness. It attends in particular to the frequently halting manner in which the vagaries of individual suffering can eventually give rise to collective action. Empathy is particularly important for such action, insofar as it allows individuals to identify with one another and, thereby, recognize common ground on which to act. To revivify the myriad insults and tragedies visited upon Nikkei in Canada and the United States thus serves to galvanize not only people of Japanese ancestry but also others of conscience who see in this shameful historical moment emotionally as well as intellectually compelling cause for exercising political agency. For that reason, this portion of the book refers to such agency as transmissible, even "contagious."

Chapter One examines the life and work of former inmate and sociologist Tamotsu Shibutani, and how the afterlife of a historical event can develop from a generalized sense of injustice and its costs into a clear topic for scholarly study and political engagement. Though Shibutani had been interested in race relations and social disincorporation long before Executive Order 9066, and had worked for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study where he gathered ample data for his graduate theses at the University of Chicago, nearly three decades would pass after his release from camp before he began publishing on the complexities of interpersonal experience and social disincorporation. This chapter treats that interval, as well as the work that came after it, as a study in the trajectory of afterlife from lingering memories to explicit analysis, and from personal experience to broad political engagement.

Chapter Two examines the growing willingness of Japanese Americans to engage in personal disclosure regarding wartime incarceration. Taking former U.S. Representative Norman Mineta as a case study, it demonstrates that Nikkei did not undertake such disclosures lightly, but rather recognized the importance of first-person singular modes of address for creating legislative coalitions. With respect to Mineta, that willingness to disclose the particulars of incarceration built on an empathetic engagement with economic and social justice that had informed his career from early on. During the pursuit of redress in the United States, however, what had been an implicit engagement with the past became explicit, so much so that it came eventually to inform Mineta's decisions concerning post-9/11 policy. In this respect, the pursuit of empathetic agency not only changed Mineta; it also changed him, rendering that agency both transmissible and reciprocal.

Shifting the geographical and cultural scope of the book, Chapter Three looks at Canadian discourses of redress in the year following the publication of Personal Justice Denied (1983). The product of a formal government inquiry, this publication galvanized Nikkei in Canada, who subsequently set about debating how best to pursue redress in that country. Recognizing profound cultural and political differences between their situation and that of Japanese Americans, they engaged in a discourse that shows how Nikkei identity in North America in the 1980s was contested, fragmentary, and at times contradictory, rather than discrete and easy to identify. Rather than produce some kind of artificially unified self-image, Japanese Canadians in pursuit of redress engaged in an ambivalent transnationality that referred to American (and Japanese) precedents even as all of the parties involved recognized the significant differences that attended each main type of Nikkei experience.

Chapter Four examines the intergenerational dynamics of afterlife, with particular attention to how third- and fourth-generation Nikkei in California have worked to perpetuate key aspects of Nikkei wartime experience. Two case studies form the heart of this chapter: the founding of formal pilgrimages to Manzanar, and the establishment of Fred Korematsu as a key figure in the narrative of incarceration and those who have fought it. In each of these cases, embodiment is crucial for the cultivation of empathetic identification and, thus, agency. Locating historical events with respect to specific sites and individuals, younger generations establish a form of continuing first-person address that demands both identification (as in the case of Korematsu) and imaginative reconstruction (in the case of Manzanar, which remains only in fragments of its original state).

Chapter Five examines the value of a college degree, taking as its focus the recipients of retroactive diplomas awarded to Nikkei who were wrongly forced from high schools and institutions of higher education after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Well into their 80s and 90s, these individuals stand to gain nothing material or economic from such action, and yet they have pursued it vigorously. No less important, so have a number of activists, most notably Mary Kitagawa, who helped persuade the University of British Columbia to award degrees to students it had expelled in 1942. The value of education, this chapter argues, lies less in its economic or even intellectual promise than in its political and social potential, particularly when thought of in terms of embodiment.

The epilogue illustrates the main conceptual strands of the book in a pair of narratives.