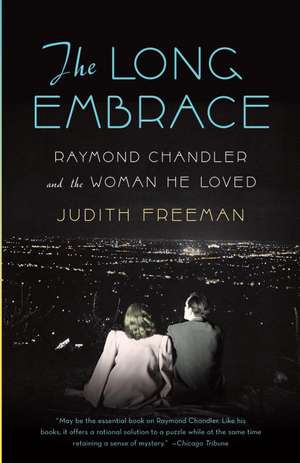

The Long Embrace: Raymond Chandler and the Woman He Loved

Autor Judith Freemanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2008

Preț: 95.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 144

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.31€ • 18.92$ • 15.24£

18.31€ • 18.92$ • 15.24£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400095179

ISBN-10: 1400095174

Pagini: 353

Ilustrații: HALFTONES THROUGHOUT; 1 MAP

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400095174

Pagini: 353

Ilustrații: HALFTONES THROUGHOUT; 1 MAP

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Judith Freeman is the author of four novels—The Chinchilla Farm, Set for Life, A Desert of Pure Feeling, and Red Water—and of Family Attractions, a collection of short stories. She lives in California.

Extras

Chapter One

In March of 1986 I began reading the collected letters of Raymond Chandler. I was at the time living in an apartment on Carondelet Street in an older part of Los Angeles where Chandler himself had once lived. My neighbors were mostly elderly people who had lived in my building for many years and with whom I had very little contact, except for one old woman who occupied the apartment above me. I had once kicked her little dog when it attempted to bite me as I came up the front steps, and for this she took to tormenting me whenever she could. She would rise early and shuffle past my bedroom window in her heavy leather slippers, speaking baby talk to her small dog or singing loudly, making as much noise as possible in order to interrupt my sleep. She broke flowers off their stems, left bits of paper scattered in my garden. Sometimes when my husband and I returned home, she would be waiting for us and lean out her window and call out in a high, shrill voice, “It’s the intelligentsia–the intelligentsia has returned!” She divided the word intelligentsia into separate syllables, flinging each one down at us as we hurried to open our door. Only in L .A., I thought, could someone make this word sound like a term of such utter derision.

I had read most of Chandler’s novels and early stories by the time I picked up the volume of his letters. In truth, I had become obsessed with Raymond Chandler. Chandler once said that great writing, whatever else it does, nags at the minds of subsequent writers who find it sometimes difficult to explain just why they are so haunted by a particular work or author. I could not deny that I had become haunted by Chandler, nor could I really explain exactly why.

As I continued to go through the letters, I also started to read a biography of Chandler, and the facts of his life began to captivate me. I was especially interested in his relationship with his wife, Cissy, who was much older than he: Chandler was thirty-five when he married Cissy Pascal, in 1924. Cissy was fifty-three, although she listed her age on their marriage certificate as forty-three. It wasn’t until much later that Chandler learned he had married a woman not eight years older, as he had thought, but eighteen. Some people believe he never learned her true age, and they could be right. In any case, only slowly, over the course of a number of years, did he figure out that his wife was indeed much older than she claimed, though he may never have known exactly how old she was.

Cissy was exceptionally beautiful and witty and sophisticated, “irresistible,” as Chandler once put it, “without even knowing it or caring much about it.” At the time she married Chandler, she was said to have the figure and sexual presence of a woman twenty years younger. She was a sensuous woman with a beautiful body, about which she felt no shame. So comfortable was she in her skin that, as Chandler once revealed, she even liked to do her housework naked. But inevitably age took its toll, and by the time Chandler published his first novel, at the age of fifty-one, Cissy was almost seventy and suffering from a lung condition that increasingly confined her to bed. She went from being a wife who offered a lot of sexual enticement to her much younger husband to being a wife who was infirm and required his constant care, whom he nursed assiduously through the abominable anarchy of old age. Still he was completely devoted to her and would later describe his marriage as “almost perfect.” When Cissy died in 1954, a few months after his sixth novel, The Long Goodbye, was published, Chandler began drinking heavily, attempted suicide, and descended into a grim state of acute alcoholism. He lived less than five years without her–five very difficult and in many ways wretched years. “My only problem,” he wrote to a friend during this period, “is that I have no home, and no one to care for if I did have one.” In reading his letters, I came to see that what Cissy had done for Chandler was to enable him to live in what Kafka called “the existent moment.” Without her he was, literally, dead.

The more I read about Chandler, the more interested in Cissy I became. I felt I knew this woman somehow, or that I could know her and possibly bring her to life if I were to try, even though very little was known about her. She left almost nothing behind at the time of her death, no writings or letters. No biographer of Chandler had ever been able to uncover much information on Cissy. The main problem was that Chandler himself ordered their letters to each other destroyed shortly before his death, even though he had planned to include them in a collection of his letters that was then being discussed and had even written to his English publisher saying, “Some of the letters to my wife are pretty hot, but I don’t want to edit anything.” In the end, he changed his mind. It was as if he decided that if he must die he would take any memory of her with him, forever keeping her to himself.

For much of Cissy’s life–or at least the years she spent married to Chandler–she was a rather reclusive woman, an “enigma,” as Chandler scholars are fond of saying. In her later years few people actually met her or were able to provide any recollections of her. Nevertheless, it seemed to me that there were enough references to her in Chandler’s letters and, in a more coded way, in his fiction, to begin to compile a portrait of her if only I could connect all the dots. And in this portrait of Cissy, in this attempt to bring her to life, I felt, lay some essence of Chandler himself, the key to his work and his personality. For I had come to believe that it was the domicile–the sanctuary he shared with Cissy and from which the world at large was excluded–that largely formed his views and helped mold the personality of the character he was famous for creating, the private eye Philip Marlowe, with whom he shared a very particular kind of loneliness as well as a sense of sexual anxiety and a code of honor. Cissy was the muse who would inform the central myth of his fiction–that of the white knight whose task it was to rescue those in peril. Actually, two women would, in distinct and yet sometimes similar ways, play this role in his life–his wife, Cissy, and his mother, Flossie (or Florence). Both women, Chandler felt, were in need of rescue and shared certain characteristics– they were almost the same age, for instance, and their names had a faintly similar ring. Yet they were also very different in personality.

Throughout that spring of 1986, I continued reading Chandler’s letters with an increasingly focused interest, making notes in a little notebook whenever I found any mention of Cissy–passages such as these, for instance:

“My wife hates snow and would never live where it is snowy. Also as a former redhead she has very sensitive skin and mosquitoes would be enough to drive her into tantrums...

My wife desires no publicity, is pretty drastic about it. She doesn’t paint or write. She does play a Steinway grand when she gets time.

My wife won’t fly or let me fly…

I make no secret of my age but printing it on the jacket of a book seems to me bad psychology. I don’t think it’s any of the public’s business. My wife is very emphatic on this point, and I have never known her to be wrong in a matter of taste.”

My wife, my wife, my wife. Rarely, if ever, does he refer to her as Cissy–just my wife, as if it was their relationship that was paramount. She seemed to me an almost sanctified or totemic figure, a woman on a pedestal (which is where Chandler liked to keep his real-life women, as opposed to his fictional females, many of whom ended up as the villains). As enigmatic or elusive as she may now appear, the actual Cissy had been, as equally, a person who managed to combine a sense of old-fashioned manners with the outlook of a libertine. She was an interesting amalgam of worldly bohemian and refined lady who took tea with her husband every afternoon, accompanied him on long drives up the California coast, made love to him in her overdecorated French boudoir, and listened with him to the same classical music program every evening for nearly thirty years. In those thirty years they were almost never apart. They lived in claustrophobic proximity, with no children and few friends to distract them from their hermetically sealed life.

In time, however, instead of searching for any mention of Cissy in Chandler’s letters, I began slowly to discover something else, something that, at least for a while, interested me almost as much as she did. I began to notice how often the addresses at the top of the letters changed, and I started making a list of these addresses, all the places in and around L.A. where the Chandlers had ever lived. Over the course of their marriage the couple had lived in more than thirty different apartments and houses (perhaps, I thought, this is part of the reason Chandler wrote so well about L.A., because he knew it from so many different angles). Sometimes they moved two or three times a year, always leasing furnished places. These moves took them all over the city and its outlying suburbs, from downtown to Santa Monica, Hollywood, the Westlake area, Pacific Palisades, Brentwood, the mid-Wilshire district, Silverlake, Arcadia, Monrovia, San Bernardino, Riverside, and Big Bear Lake, and Idyllwild in the mountains above L.A., and the desert towns of Palm Springs and Cathedral City, until finally he and Cissy bought a house in the charming coastal village of La Jolla, an hour and a half south of L.A., where they settled down for Cissy’s few remaining years. The question I kept asking myself was, Why had they moved so often?

It was a question that began to absorb me. I decided to track down every address where Chandler had ever lived in L.A. and photograph what I found. It would be like detective work, I thought. I knew what I was looking for: I was searching for any trace of their lives, anything that would help me understand Raymond and Cissy Chandler – anything, in other words, that might feed my obsession with a writer whose work I so admired and the wife who had begun to fascinate me. I would be looking for a dead writer, and his mysterious spouse, in a city I knew very well and whose unique distillation of qualities had been first described by Chandler, who at once captured the essence of Los Angeles and transformed it into myth. His work was forever wedded to the city, just as the city would always bear the stigma (if one can call it that) of his rather dark and violent vision. As a friend said to me when we were discussing Chandler, Funny how L.A. made him the writer he was and in return he gave the city a lasting image.

It was this mirror world of author and metropolis that began to fascinate me.

Often, as the weeks passed, during which time I was engrossed in rereading Chandler’s letters, I would break off my reading and head out into the city to explore one or another locale he had mentioned. I remember one afternoon going to the old Union Station, the railroad depot in the oldest part of downtown L.A., located near Olvera Street, the touristy area of little Mexican restaurants and shops where the original Pueblo of Los Angeles was located and where one could still visit the old adobe hacienda owned by the first Spanish land-grant family who settled here. As far as I could tell, Union Station looked pretty much as it had when Chandler described it in Playback, his final novel, except that it no longer handled the rail traffic that it once had when it was first built in the mid-1930s. The interior was still resplendent, with Spanish tiles and graceful vaulted archways, and the palms and jacarandas growing in front of the station looked as if they had been there from the beginning. The only difference seemed to be that now many fewer trains arrived and departed each day, and the huge vaulted waiting room appeared almost eerily empty, although here and there a person could be seen sitting in one of the padded high-back wooden seats, quietly reading a book or gazing around the room, eyeing the occasional fellow passenger with lingering interest.

Not many people in America traveled by train anymore, especially on the West Coast, and the station had a somewhat haunted feeling. A great portion of the lobby had been cordoned off by a metal grating and was no longer used, the section with the long row of windows where tickets were once sold. I assumed people now bought their tickets over the Internet or by telephone. Looking through the grating at the cordoned-off area, I thought how ghostly and still it seemed in there, and I imagined how it must once have teemed with travelers, embarking on and disembarking from the great railway trains such as the Sunset Limited, the California Zephyr, and the Santa Fe Super Chief, the glittering, streamlined transcontinental train that used to link L .A. with the rest of America, bringing the stars and those longing for Hollywood fame as well as ordinary Americans to the new city of dreams before airlines took the business away.

It was the Super Chief that brought Eleanor King to L.A. Eleanor, the heroine of Playback–an “unhappy girl, if I ever saw one,” as Philip Marlowe says. I had brought along a copy of Playback and I sat down in the lobby of the cavernous train station and opened it and read the description of her as she arrives in the station and enters the lobby where I was then sitting:

“She wasn’t carrying anything but a paperback which she dumped in the first trash can she came to. She sat down and looked at the floor . . . After a while she got up and went to the book rack. She left without picking anything out, glanced at the big clock on the wall and shut herself up in a telephone booth. She talked to someone after putting a handful of silver into the slot. Her expression didn’t change at all. She hung up and went to the magazine rack, picked up a New Yorker, looked at her watch again, and sat down to read.

She was wearing a midnight blue tailor-made suit with a white blouse showing at the neck and a big sapphire-blue lapel pin which would probably have matched her earrings, if I could see her ears. Her hair was a dusky red….her dark blue ribbon hat had a short veil hanging from it. She was wearing gloves.”

From the Hardcover edition.

In March of 1986 I began reading the collected letters of Raymond Chandler. I was at the time living in an apartment on Carondelet Street in an older part of Los Angeles where Chandler himself had once lived. My neighbors were mostly elderly people who had lived in my building for many years and with whom I had very little contact, except for one old woman who occupied the apartment above me. I had once kicked her little dog when it attempted to bite me as I came up the front steps, and for this she took to tormenting me whenever she could. She would rise early and shuffle past my bedroom window in her heavy leather slippers, speaking baby talk to her small dog or singing loudly, making as much noise as possible in order to interrupt my sleep. She broke flowers off their stems, left bits of paper scattered in my garden. Sometimes when my husband and I returned home, she would be waiting for us and lean out her window and call out in a high, shrill voice, “It’s the intelligentsia–the intelligentsia has returned!” She divided the word intelligentsia into separate syllables, flinging each one down at us as we hurried to open our door. Only in L .A., I thought, could someone make this word sound like a term of such utter derision.

I had read most of Chandler’s novels and early stories by the time I picked up the volume of his letters. In truth, I had become obsessed with Raymond Chandler. Chandler once said that great writing, whatever else it does, nags at the minds of subsequent writers who find it sometimes difficult to explain just why they are so haunted by a particular work or author. I could not deny that I had become haunted by Chandler, nor could I really explain exactly why.

As I continued to go through the letters, I also started to read a biography of Chandler, and the facts of his life began to captivate me. I was especially interested in his relationship with his wife, Cissy, who was much older than he: Chandler was thirty-five when he married Cissy Pascal, in 1924. Cissy was fifty-three, although she listed her age on their marriage certificate as forty-three. It wasn’t until much later that Chandler learned he had married a woman not eight years older, as he had thought, but eighteen. Some people believe he never learned her true age, and they could be right. In any case, only slowly, over the course of a number of years, did he figure out that his wife was indeed much older than she claimed, though he may never have known exactly how old she was.

Cissy was exceptionally beautiful and witty and sophisticated, “irresistible,” as Chandler once put it, “without even knowing it or caring much about it.” At the time she married Chandler, she was said to have the figure and sexual presence of a woman twenty years younger. She was a sensuous woman with a beautiful body, about which she felt no shame. So comfortable was she in her skin that, as Chandler once revealed, she even liked to do her housework naked. But inevitably age took its toll, and by the time Chandler published his first novel, at the age of fifty-one, Cissy was almost seventy and suffering from a lung condition that increasingly confined her to bed. She went from being a wife who offered a lot of sexual enticement to her much younger husband to being a wife who was infirm and required his constant care, whom he nursed assiduously through the abominable anarchy of old age. Still he was completely devoted to her and would later describe his marriage as “almost perfect.” When Cissy died in 1954, a few months after his sixth novel, The Long Goodbye, was published, Chandler began drinking heavily, attempted suicide, and descended into a grim state of acute alcoholism. He lived less than five years without her–five very difficult and in many ways wretched years. “My only problem,” he wrote to a friend during this period, “is that I have no home, and no one to care for if I did have one.” In reading his letters, I came to see that what Cissy had done for Chandler was to enable him to live in what Kafka called “the existent moment.” Without her he was, literally, dead.

The more I read about Chandler, the more interested in Cissy I became. I felt I knew this woman somehow, or that I could know her and possibly bring her to life if I were to try, even though very little was known about her. She left almost nothing behind at the time of her death, no writings or letters. No biographer of Chandler had ever been able to uncover much information on Cissy. The main problem was that Chandler himself ordered their letters to each other destroyed shortly before his death, even though he had planned to include them in a collection of his letters that was then being discussed and had even written to his English publisher saying, “Some of the letters to my wife are pretty hot, but I don’t want to edit anything.” In the end, he changed his mind. It was as if he decided that if he must die he would take any memory of her with him, forever keeping her to himself.

For much of Cissy’s life–or at least the years she spent married to Chandler–she was a rather reclusive woman, an “enigma,” as Chandler scholars are fond of saying. In her later years few people actually met her or were able to provide any recollections of her. Nevertheless, it seemed to me that there were enough references to her in Chandler’s letters and, in a more coded way, in his fiction, to begin to compile a portrait of her if only I could connect all the dots. And in this portrait of Cissy, in this attempt to bring her to life, I felt, lay some essence of Chandler himself, the key to his work and his personality. For I had come to believe that it was the domicile–the sanctuary he shared with Cissy and from which the world at large was excluded–that largely formed his views and helped mold the personality of the character he was famous for creating, the private eye Philip Marlowe, with whom he shared a very particular kind of loneliness as well as a sense of sexual anxiety and a code of honor. Cissy was the muse who would inform the central myth of his fiction–that of the white knight whose task it was to rescue those in peril. Actually, two women would, in distinct and yet sometimes similar ways, play this role in his life–his wife, Cissy, and his mother, Flossie (or Florence). Both women, Chandler felt, were in need of rescue and shared certain characteristics– they were almost the same age, for instance, and their names had a faintly similar ring. Yet they were also very different in personality.

Throughout that spring of 1986, I continued reading Chandler’s letters with an increasingly focused interest, making notes in a little notebook whenever I found any mention of Cissy–passages such as these, for instance:

“My wife hates snow and would never live where it is snowy. Also as a former redhead she has very sensitive skin and mosquitoes would be enough to drive her into tantrums...

My wife desires no publicity, is pretty drastic about it. She doesn’t paint or write. She does play a Steinway grand when she gets time.

My wife won’t fly or let me fly…

I make no secret of my age but printing it on the jacket of a book seems to me bad psychology. I don’t think it’s any of the public’s business. My wife is very emphatic on this point, and I have never known her to be wrong in a matter of taste.”

My wife, my wife, my wife. Rarely, if ever, does he refer to her as Cissy–just my wife, as if it was their relationship that was paramount. She seemed to me an almost sanctified or totemic figure, a woman on a pedestal (which is where Chandler liked to keep his real-life women, as opposed to his fictional females, many of whom ended up as the villains). As enigmatic or elusive as she may now appear, the actual Cissy had been, as equally, a person who managed to combine a sense of old-fashioned manners with the outlook of a libertine. She was an interesting amalgam of worldly bohemian and refined lady who took tea with her husband every afternoon, accompanied him on long drives up the California coast, made love to him in her overdecorated French boudoir, and listened with him to the same classical music program every evening for nearly thirty years. In those thirty years they were almost never apart. They lived in claustrophobic proximity, with no children and few friends to distract them from their hermetically sealed life.

In time, however, instead of searching for any mention of Cissy in Chandler’s letters, I began slowly to discover something else, something that, at least for a while, interested me almost as much as she did. I began to notice how often the addresses at the top of the letters changed, and I started making a list of these addresses, all the places in and around L.A. where the Chandlers had ever lived. Over the course of their marriage the couple had lived in more than thirty different apartments and houses (perhaps, I thought, this is part of the reason Chandler wrote so well about L.A., because he knew it from so many different angles). Sometimes they moved two or three times a year, always leasing furnished places. These moves took them all over the city and its outlying suburbs, from downtown to Santa Monica, Hollywood, the Westlake area, Pacific Palisades, Brentwood, the mid-Wilshire district, Silverlake, Arcadia, Monrovia, San Bernardino, Riverside, and Big Bear Lake, and Idyllwild in the mountains above L.A., and the desert towns of Palm Springs and Cathedral City, until finally he and Cissy bought a house in the charming coastal village of La Jolla, an hour and a half south of L.A., where they settled down for Cissy’s few remaining years. The question I kept asking myself was, Why had they moved so often?

It was a question that began to absorb me. I decided to track down every address where Chandler had ever lived in L.A. and photograph what I found. It would be like detective work, I thought. I knew what I was looking for: I was searching for any trace of their lives, anything that would help me understand Raymond and Cissy Chandler – anything, in other words, that might feed my obsession with a writer whose work I so admired and the wife who had begun to fascinate me. I would be looking for a dead writer, and his mysterious spouse, in a city I knew very well and whose unique distillation of qualities had been first described by Chandler, who at once captured the essence of Los Angeles and transformed it into myth. His work was forever wedded to the city, just as the city would always bear the stigma (if one can call it that) of his rather dark and violent vision. As a friend said to me when we were discussing Chandler, Funny how L.A. made him the writer he was and in return he gave the city a lasting image.

It was this mirror world of author and metropolis that began to fascinate me.

Often, as the weeks passed, during which time I was engrossed in rereading Chandler’s letters, I would break off my reading and head out into the city to explore one or another locale he had mentioned. I remember one afternoon going to the old Union Station, the railroad depot in the oldest part of downtown L.A., located near Olvera Street, the touristy area of little Mexican restaurants and shops where the original Pueblo of Los Angeles was located and where one could still visit the old adobe hacienda owned by the first Spanish land-grant family who settled here. As far as I could tell, Union Station looked pretty much as it had when Chandler described it in Playback, his final novel, except that it no longer handled the rail traffic that it once had when it was first built in the mid-1930s. The interior was still resplendent, with Spanish tiles and graceful vaulted archways, and the palms and jacarandas growing in front of the station looked as if they had been there from the beginning. The only difference seemed to be that now many fewer trains arrived and departed each day, and the huge vaulted waiting room appeared almost eerily empty, although here and there a person could be seen sitting in one of the padded high-back wooden seats, quietly reading a book or gazing around the room, eyeing the occasional fellow passenger with lingering interest.

Not many people in America traveled by train anymore, especially on the West Coast, and the station had a somewhat haunted feeling. A great portion of the lobby had been cordoned off by a metal grating and was no longer used, the section with the long row of windows where tickets were once sold. I assumed people now bought their tickets over the Internet or by telephone. Looking through the grating at the cordoned-off area, I thought how ghostly and still it seemed in there, and I imagined how it must once have teemed with travelers, embarking on and disembarking from the great railway trains such as the Sunset Limited, the California Zephyr, and the Santa Fe Super Chief, the glittering, streamlined transcontinental train that used to link L .A. with the rest of America, bringing the stars and those longing for Hollywood fame as well as ordinary Americans to the new city of dreams before airlines took the business away.

It was the Super Chief that brought Eleanor King to L.A. Eleanor, the heroine of Playback–an “unhappy girl, if I ever saw one,” as Philip Marlowe says. I had brought along a copy of Playback and I sat down in the lobby of the cavernous train station and opened it and read the description of her as she arrives in the station and enters the lobby where I was then sitting:

“She wasn’t carrying anything but a paperback which she dumped in the first trash can she came to. She sat down and looked at the floor . . . After a while she got up and went to the book rack. She left without picking anything out, glanced at the big clock on the wall and shut herself up in a telephone booth. She talked to someone after putting a handful of silver into the slot. Her expression didn’t change at all. She hung up and went to the magazine rack, picked up a New Yorker, looked at her watch again, and sat down to read.

She was wearing a midnight blue tailor-made suit with a white blouse showing at the neck and a big sapphire-blue lapel pin which would probably have matched her earrings, if I could see her ears. Her hair was a dusky red….her dark blue ribbon hat had a short veil hanging from it. She was wearing gloves.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Part biography, part detective story, part love story, and part séance, The Long Embrace takes us on Judith Freeman’s journey to discover the private Raymond Chandler through the lens of his marriage to a woman eighteen years older than himself, a woman he adored and yet whose every scrap of correspondence he destroyed following her death. Lively, quirky, revealing of both author and subject, this is a welcome addition to any Chandler addict’s library.”—Janet Fitch, author of White Oleander“This elegant, stirring book plumbs a great mystery, one hidden, from even Chandler’s many devoted readers, in plain sight. Freeman’s book is a meditation on marriage, a persuasive biographical and literary study, and, best of all, one of those rare books, like Nicholson Baker’s U and I or Geoff Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage, where one writer’s study of another takes the form of a confessional fugue on the writing act itself.” —Jonathan Lethem, author of The Fortress of Solitude“A compelling picture of present-day Los Angeles and a compelling dual portrait of Chandler and his wife . . . Ms. Freeman knows the territory as well as Marlowe himself . . . she feels the language and captures the mood. Like Cissy, when she crooks her finger, it’s impossible not to follow.”—The New York Times“A beautiful and original book. . . Freeman writes about L.A. with a tender precision and yearning that borders on the religious. . . In "The Long Embrace," magic has occurred. Freeman's identification with her subject is so complete we feel we're there with Chandler too.”—The Los Angeles Times"The Long Embrace" may be the essential book on Raymond Chandler. Like his books, it offers a rational solution to a puzzle while at the same time retaining a sense of mystery.”—The Chicago Tribune“An invaluable prism to understand Raymond Chandler, his wife and most of all Los Angeles and its environs, of which he became the literary champion . . . Ms. Freeman's intuitive understanding of the writer and his terrain make her the perfect person to ask the right questions . . . Ms. Freeman not only establishes the centrality of Cissy to Chandler's life and art, she actually succeeds in making the reader feel their passion.”—The Washington Times“Compelling biography . . . a novelist's nonfiction triumph.”—The Pittsburgh Post-GazetteIn this unusual, beautifully modulated study, Judith Freeman gives us a probing look at Chandler and his inspirations . . . [Freeman] is a wonderfully astute critic of Chandler's writing, and poignant explainer of the torments that fed his vision . . . What makes this an exceptional book is the way Freeman merges her own personal obsession with Chandler with a haunting meditation on Los Angeles. Few writers have revealed the essence of this chronically misunderstood city so well.—Newsday“A fascinating book”—The Tuscon Citizen “An acute and empathic study . . . Freeman does some fine literary detective work.”—The Guardian