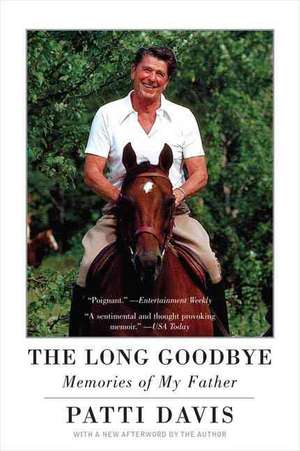

The Long Goodbye

Autor Patti Davisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 27 sep 2005

In The Long Goodbye, Patti Davis describes losing her father to Alzheimer’s disease, saying goodbye in stages, helpless against the onslaught of a disease that steals what is most precious—a person’s memory. “Alzheimer’s,” she writes, “snips away at the threads, a slow unraveling, a steady retreat; as a witness all you can do is watch, cry, and whisper a soft stream of goodbyes.”

She writes of needing to be reunited at forty-two with her mother, of regaining what they had spent decades demolishing. A truce was necessary to bring together a splintered family, a few weeks before her father released his letter telling the country and the world of his illness. The author delves into her memories to touch her father again, to hear his voice, to keep alive the years she had with him.

Moving and honest, an illuminating portrait of grief, of a great man, a disease, and a woman and her father.

She writes of needing to be reunited at forty-two with her mother, of regaining what they had spent decades demolishing. A truce was necessary to bring together a splintered family, a few weeks before her father released his letter telling the country and the world of his illness. The author delves into her memories to touch her father again, to hear his voice, to keep alive the years she had with him.

Moving and honest, an illuminating portrait of grief, of a great man, a disease, and a woman and her father.

Preț: 130.12 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 195

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.90€ • 25.90$ • 20.56£

24.90€ • 25.90$ • 20.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780452286870

ISBN-10: 0452286875

Pagini: 226

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Penguin Publishing Group

ISBN-10: 0452286875

Pagini: 226

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Penguin Publishing Group

Recenzii

"A sentimental and thought provoking memoir." —USA Today

"[A] frank reflection on the often difficult, sometime tumultuous relations between parents and children." —Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"[A] genuine and heartfelt chronology of one person’s passing and its effect on those who are unwitting bystanders." —San Diego Union-Tribune

"[A] frank reflection on the often difficult, sometime tumultuous relations between parents and children." —Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"[A] genuine and heartfelt chronology of one person’s passing and its effect on those who are unwitting bystanders." —San Diego Union-Tribune

Notă biografică

Patti Davis is the author of five books, including The Way I See It and Angels Don’t Die. Her articles have appeared in many magazines and newspapers, among them Time, Newsweek, Harper’s Bazaar, Town &Country, Vanity Fair, The Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times.

Extras

April 1995

When I got married in 1984, my father gave a toast at my wedding. I don’t remember his exact words, but they had to do with his recollection of how tiny my hand once was, as a child holding on to his, and how so many years later, he was giving my hand in marriage. An older hand, a woman’s hand.

These days, I find myself looking at my father’s hands. They seem to have grown smaller, a bit more frail. It’s as if they no longer need to grasp life, stretch themselves around it; rather, they are learning to let it go. It’s a soft release, not like the Dylan Thomas poem I once embraced: “Do not go gentle into that good night, / Old age should burn and rave at close of day.”

I still like that poem; I like its fury and its fierce passion. But I think my father’s way is sweeter.

I watch his eyes these days, too. They shimmer across some unfathomable distance, content to watch from wherever his mind has alighted. If I turn into his eyes, it’s like turning into a calm breeze. The serenity is contagious.

The tendency when you’re around someone with Alzheimer’s is to try to reel them back in, include them in the conversation, pique their interest in whatever you happen to be discussing. But I stopped doing that because it seemed to me that I was intruding. Wherever he was, he was content. Wherever he was, he shouldn’t be disturbed.

At the ranch we owned when I was younger, my father taught me that when a horse was growing older, when riding it would be unkind and possibly harmful, the horse should be allowed a more peaceful life, roaming in the acres of pasture that ourranch provided. I remember several of our horses living out the remainder of their days in wide, green fields, grazing. That’s how I think of my father now; it’s what I see in his eyes. Things are calmer where he is—most of the time, anyway. And he grazes—on the moments and hours that are left to him. On the sight of afternoon sun gilding the lawn or clouds skimming across the sky. On his family, who have finally learned how to laugh together, and how to love. He grazes on the taste of life as it slips away—the rich, fertile moments that must be released into the wind, because that’s what you do if you’re like my father, his hand reaching for God’s, leaving ours behind, saying goodbye in small ways, getting us used to his absence.

I haven’t read any of the books on Alzheimer’s. I probably should, but I don’t want my thoughts to be cluttered with other people’s impressions, or with medical predictions and evaluations. I want to keep watching my father’s hands. I want to remember how they’ve changed, how uncallused and tender they’ve become. And I want to chart his distance from his eyes. They’re a map, but you have to look closely. Sometimes, I think I actually see him leaving, retreating, navigating his way out of this world and into the next. Other times, I see him right there, as if he’s preserving each moment under glass.

When daylight saving time dictated that we should move our clocks ahead an hour, I thought of my father. My mother said that the first clock she changed was his watch. He looks at his watch often now—I’m not sure why. Is it that time seems to be moving faster, and he wants to chase after it by marking its passage? Or does each time of day now have a special significance? Either way, losing an hour of time must have had more of an impact on him than it did on most of us. Life is measured in time—in years, months, hours. And one hour just vanished. It wasn’t wasted; it wasn’t squandered by daydreaming or staring out the window. It was snatched away, erased—because someone decided it should be. I try to see things sometimes as he must. He lives more in the moment now. It’s one thing I have learned about Alzheimer’s—the past and the future are risky subjects. It occurs to me that it must seem unfair to him that a precious hour—a measurement of life—could so easily be discarded, erased from the map of time. Yet it also occurs to me that, in one way, he is living as we all should—in the present moment.

I hold on to this as a tiny gift in the midst of a sad time. I suppose it’s what happens when one sees a horizon darkened by disease or loss—there are always thin rays of light. You have to be on the alert for them, and hold on tightly to them.

May 1995, Los Angeles

On Sunday morning, I went to church with my parents. It’s something my father looks forward to all week, and I wanted to share the experience; I wanted to watch him, absorb some of his reverence.

He remembers every word of the Lord’s Prayer. He was looking straight ahead, to the pulpit and the tall wooden cross behind it, reciting the prayer along with everyone else, never missing a syllable. The same thing happened with the doxology: “Praise God from whom all blessings flow . . .” He sang it perfectly.

I thought about the mysteries of this thing we call memory. Even being encroached upon by something as relentless as Alzheimer’s, the memory has pockets that resist the progression of time and the steady march of disease. It’s fitting that, in my father’s case, those pockets contain hymns and prayers. They are his treasures; they always have been—the shiny stones he turns over in his hand, keeping them polished and smooth. I closed my eyes for a moment as I sat between my parents and prayed that he will always be able to recite the Lord’s Prayer, always recall a hymn. I asked God to keep his treasures safe.

•••

My mother and I talk about death now as if we are resigning ourselves to its presence, growing more comfortable with having it around, lurking nearby. At the moment, it’s a shadow on the wall, but one that’s lengthening, one that won’t go home at dawn. I’m reminded of Don Juan’s counsel in Carlos Castaneda’s books. He said that death is our constant companion, that it travels on our left shoulder, and that our task must be to make it our “ally.”

I feel, in my conversations with my mother, that we are both making friends with this shadowy presence, this unwelcome guest. Because the enemy—the true messenger of terror—would be the full progression of Alzheimer’s. I never want to see the day when my father stands up in church and is unable to remember the Lord’s Prayer. I would rather watch him turn toward his left shoulder and say, “All right, I’m ready now.”

Frequently these days, my mother and I remind each other that the grieving process has already begun. It’s a mountainous journey, and we need to be reassured that we’ve already covered some miles. It’s as if we are passing a canteen of water back and forth—it doesn’t shorten the distance, but it helps.

When I say “I love you” to my father now, I’m deliberate and focused about it. I say it straight into his eyes, straight into the deepest currents of his soul. I want the words to be like those of the Lord’s Prayer—ones he won’t forget, ones that will resist the onslaught of disease.

We all have a passage out of this world and into the next. This is my father’s, as sad as it is for those of us around him who don’t want anything to be wrong with him. But ultimately, it will be his passage home. That’s what he always told me: God will come to each of us when he’s ready, and he will take us home.

My father made heaven sound so lovely—a peaceful, green kingdom in which all living creatures get along. A celestial Noah’s Ark. When one of my fish died, he and I scooped it out of the aquarium and gave it a funeral. My father tied sticks together to form a cross, which he placed on the tiny grave; he gave my fish a brief eulogy and described to me the clear blue waters it would be swimming in up in heaven. I could see the water—blue as the sky, endless, and teeming with other fish, none of whom would eat one another. I became so enchanted with this vision that I felt sorry for my other fish, condemned to the small, unnatural environment of the aquarium, with its colored rocks and gray plastic castle.

“Maybe we should kill the others,” I said to my father, eager to give them the same freedom, the same beauty as my newly departed fish.

He told me, in God’s time, the others would go too.

I go back to childhood to retrieve the stories that once made me feel better, hoping that they still have the same effect. I became less certain as I got older. When did I stop imagining a green-and-blue paradise on the other side? When did fear throw it in shadow? I need to return to the stories in order to let my father go.

When I got married in 1984, my father gave a toast at my wedding. I don’t remember his exact words, but they had to do with his recollection of how tiny my hand once was, as a child holding on to his, and how so many years later, he was giving my hand in marriage. An older hand, a woman’s hand.

These days, I find myself looking at my father’s hands. They seem to have grown smaller, a bit more frail. It’s as if they no longer need to grasp life, stretch themselves around it; rather, they are learning to let it go. It’s a soft release, not like the Dylan Thomas poem I once embraced: “Do not go gentle into that good night, / Old age should burn and rave at close of day.”

I still like that poem; I like its fury and its fierce passion. But I think my father’s way is sweeter.

I watch his eyes these days, too. They shimmer across some unfathomable distance, content to watch from wherever his mind has alighted. If I turn into his eyes, it’s like turning into a calm breeze. The serenity is contagious.

The tendency when you’re around someone with Alzheimer’s is to try to reel them back in, include them in the conversation, pique their interest in whatever you happen to be discussing. But I stopped doing that because it seemed to me that I was intruding. Wherever he was, he was content. Wherever he was, he shouldn’t be disturbed.

At the ranch we owned when I was younger, my father taught me that when a horse was growing older, when riding it would be unkind and possibly harmful, the horse should be allowed a more peaceful life, roaming in the acres of pasture that ourranch provided. I remember several of our horses living out the remainder of their days in wide, green fields, grazing. That’s how I think of my father now; it’s what I see in his eyes. Things are calmer where he is—most of the time, anyway. And he grazes—on the moments and hours that are left to him. On the sight of afternoon sun gilding the lawn or clouds skimming across the sky. On his family, who have finally learned how to laugh together, and how to love. He grazes on the taste of life as it slips away—the rich, fertile moments that must be released into the wind, because that’s what you do if you’re like my father, his hand reaching for God’s, leaving ours behind, saying goodbye in small ways, getting us used to his absence.

I haven’t read any of the books on Alzheimer’s. I probably should, but I don’t want my thoughts to be cluttered with other people’s impressions, or with medical predictions and evaluations. I want to keep watching my father’s hands. I want to remember how they’ve changed, how uncallused and tender they’ve become. And I want to chart his distance from his eyes. They’re a map, but you have to look closely. Sometimes, I think I actually see him leaving, retreating, navigating his way out of this world and into the next. Other times, I see him right there, as if he’s preserving each moment under glass.

When daylight saving time dictated that we should move our clocks ahead an hour, I thought of my father. My mother said that the first clock she changed was his watch. He looks at his watch often now—I’m not sure why. Is it that time seems to be moving faster, and he wants to chase after it by marking its passage? Or does each time of day now have a special significance? Either way, losing an hour of time must have had more of an impact on him than it did on most of us. Life is measured in time—in years, months, hours. And one hour just vanished. It wasn’t wasted; it wasn’t squandered by daydreaming or staring out the window. It was snatched away, erased—because someone decided it should be. I try to see things sometimes as he must. He lives more in the moment now. It’s one thing I have learned about Alzheimer’s—the past and the future are risky subjects. It occurs to me that it must seem unfair to him that a precious hour—a measurement of life—could so easily be discarded, erased from the map of time. Yet it also occurs to me that, in one way, he is living as we all should—in the present moment.

I hold on to this as a tiny gift in the midst of a sad time. I suppose it’s what happens when one sees a horizon darkened by disease or loss—there are always thin rays of light. You have to be on the alert for them, and hold on tightly to them.

May 1995, Los Angeles

On Sunday morning, I went to church with my parents. It’s something my father looks forward to all week, and I wanted to share the experience; I wanted to watch him, absorb some of his reverence.

He remembers every word of the Lord’s Prayer. He was looking straight ahead, to the pulpit and the tall wooden cross behind it, reciting the prayer along with everyone else, never missing a syllable. The same thing happened with the doxology: “Praise God from whom all blessings flow . . .” He sang it perfectly.

I thought about the mysteries of this thing we call memory. Even being encroached upon by something as relentless as Alzheimer’s, the memory has pockets that resist the progression of time and the steady march of disease. It’s fitting that, in my father’s case, those pockets contain hymns and prayers. They are his treasures; they always have been—the shiny stones he turns over in his hand, keeping them polished and smooth. I closed my eyes for a moment as I sat between my parents and prayed that he will always be able to recite the Lord’s Prayer, always recall a hymn. I asked God to keep his treasures safe.

•••

My mother and I talk about death now as if we are resigning ourselves to its presence, growing more comfortable with having it around, lurking nearby. At the moment, it’s a shadow on the wall, but one that’s lengthening, one that won’t go home at dawn. I’m reminded of Don Juan’s counsel in Carlos Castaneda’s books. He said that death is our constant companion, that it travels on our left shoulder, and that our task must be to make it our “ally.”

I feel, in my conversations with my mother, that we are both making friends with this shadowy presence, this unwelcome guest. Because the enemy—the true messenger of terror—would be the full progression of Alzheimer’s. I never want to see the day when my father stands up in church and is unable to remember the Lord’s Prayer. I would rather watch him turn toward his left shoulder and say, “All right, I’m ready now.”

Frequently these days, my mother and I remind each other that the grieving process has already begun. It’s a mountainous journey, and we need to be reassured that we’ve already covered some miles. It’s as if we are passing a canteen of water back and forth—it doesn’t shorten the distance, but it helps.

When I say “I love you” to my father now, I’m deliberate and focused about it. I say it straight into his eyes, straight into the deepest currents of his soul. I want the words to be like those of the Lord’s Prayer—ones he won’t forget, ones that will resist the onslaught of disease.

We all have a passage out of this world and into the next. This is my father’s, as sad as it is for those of us around him who don’t want anything to be wrong with him. But ultimately, it will be his passage home. That’s what he always told me: God will come to each of us when he’s ready, and he will take us home.

My father made heaven sound so lovely—a peaceful, green kingdom in which all living creatures get along. A celestial Noah’s Ark. When one of my fish died, he and I scooped it out of the aquarium and gave it a funeral. My father tied sticks together to form a cross, which he placed on the tiny grave; he gave my fish a brief eulogy and described to me the clear blue waters it would be swimming in up in heaven. I could see the water—blue as the sky, endless, and teeming with other fish, none of whom would eat one another. I became so enchanted with this vision that I felt sorry for my other fish, condemned to the small, unnatural environment of the aquarium, with its colored rocks and gray plastic castle.

“Maybe we should kill the others,” I said to my father, eager to give them the same freedom, the same beauty as my newly departed fish.

He told me, in God’s time, the others would go too.

I go back to childhood to retrieve the stories that once made me feel better, hoping that they still have the same effect. I became less certain as I got older. When did I stop imagining a green-and-blue paradise on the other side? When did fear throw it in shadow? I need to return to the stories in order to let my father go.