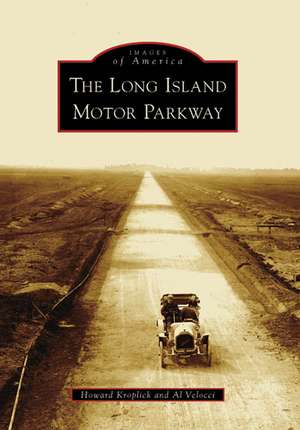

The Long Island Motor Parkway: Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

Autor Howard Kroplick, Al Veloccien Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2008

Din seria Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

-

Preț: 129.71 lei

Preț: 129.71 lei -

Preț: 129.71 lei

Preț: 129.71 lei -

Preț: 130.74 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei -

Preț: 129.71 lei

Preț: 129.71 lei -

Preț: 125.22 lei

Preț: 125.22 lei -

Preț: 130.74 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei -

Preț: 130.74 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei -

Preț: 130.92 lei

Preț: 130.92 lei -

Preț: 132.42 lei

Preț: 132.42 lei -

Preț: 115.50 lei

Preț: 115.50 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 129.49 lei

Preț: 129.49 lei -

Preț: 115.72 lei

Preț: 115.72 lei -

Preț: 126.07 lei

Preț: 126.07 lei -

Preț: 131.55 lei

Preț: 131.55 lei -

Preț: 127.30 lei

Preț: 127.30 lei -

Preț: 115.72 lei

Preț: 115.72 lei -

Preț: 131.16 lei

Preț: 131.16 lei -

Preț: 126.26 lei

Preț: 126.26 lei -

Preț: 132.42 lei

Preț: 132.42 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 129.71 lei

Preț: 129.71 lei -

Preț: 126.26 lei

Preț: 126.26 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 126.26 lei

Preț: 126.26 lei -

Preț: 131.79 lei

Preț: 131.79 lei -

Preț: 118.36 lei

Preț: 118.36 lei -

Preț: 125.22 lei

Preț: 125.22 lei -

Preț: 126.67 lei

Preț: 126.67 lei -

Preț: 130.74 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei -

Preț: 135.25 lei

Preț: 135.25 lei -

Preț: 132.18 lei

Preț: 132.18 lei -

Preț: 116.31 lei

Preț: 116.31 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 132.18 lei

Preț: 132.18 lei -

Preț: 130.92 lei

Preț: 130.92 lei -

Preț: 131.15 lei

Preț: 131.15 lei -

Preț: 131.15 lei

Preț: 131.15 lei -

Preț: 130.74 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 130.74 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei -

Preț: 131.15 lei

Preț: 131.15 lei -

Preț: 130.75 lei

Preț: 130.75 lei -

Preț: 130.97 lei

Preț: 130.97 lei -

Preț: 127.08 lei

Preț: 127.08 lei -

Preț: 129.71 lei

Preț: 129.71 lei -

Preț: 176.03 lei

Preț: 176.03 lei -

Preț: 116.13 lei

Preț: 116.13 lei

Preț: 130.74 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 196

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.03€ • 25.82$ • 20.75£

25.03€ • 25.82$ • 20.75£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780738557939

ISBN-10: 0738557935

Pagini: 127

Dimensiuni: 163 x 231 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Arcadia Publishing (SC)

Seria Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

ISBN-10: 0738557935

Pagini: 127

Dimensiuni: 163 x 231 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Arcadia Publishing (SC)

Seria Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

Descriere

A forerunner of the modern highway system, the Long Island Motor Parkway was constructed during the advent of the automobile and at a pivotal time in American history. Following a spectator death during the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup Race, the concept for a privately owned speedway on Long Island was developed by William K. Vanderbilt Jr. and his business associates. It would be the first highway built exclusively for the automobile. Vanderbilt's dream was to build a safe, smooth, police-free road without speed limits where he could conduct his beloved automobile races without spectators running onto the course. Features such as the use of reinforced concrete, bridges to eliminate grade crossings, banked curves, guardrails, and landscaping were all pioneered for the parkway. Reflecting its poor profitability and the availability of free state-built public parkways, the historic 48-mile Long Island Motor Parkway closed on Easter Sunday, April 17, 1938.

Recenzii

Publication: The New York Times

Article Title: A 100-Year-Old Dream: A Road Just for Cars

Author: Phil Patton

Date: October 12th, 2008

It survives only as segments of other highways, as a right of way for power lines and as a bike trail, but the Long Island Motor Parkway still holds a sense of magic as what some historians say is the countryas first road built specifically for the automobile. It opened 100 years ago last Friday as a rich manas dream.

As detailed in a new book, aThe Long Island Motor Parkwaya by Howard Kroplick and Al Velocci (Arcadia Publishing), the parkway ran about 45 miles across Long Island, from Queens to Ronkonkoma, and was created by William Kissam Vanderbilt II, the great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The younger Vanderbilt was a car enthusiast who loved to race. He had set a speed record of 92 miles an hour in 1904, the same year he created his own race, the Vanderbilt Cup.

But his race came under fire after a spectator was killed in 1906, and Vanderbilt wanted a safe road on which to hold the race and on which other car lovers could hurl their new machines free of the dust common on roads made for horses. The parkway would also be free of ainterference from the authorities, a he said in a speech.

So he created a toll road for high-speed automobile travel. It was built of reinforced concrete, had banked turns, guard rails and, by building bridges, he eliminated intersections that would slow a driver down. The Long Island Motor Parkway officially opened on Oct. 10, 1908, and closed in 1938.

Paul Daniel Marriott, a highway historian and consultant in Washington, said road designers began to take the carinto account around 1900. Like Vanderbilt, these early car owners were mostly wealthy men; they were called aautomobilistsa on the model of abicyclists.a

aCars were seen as objects for leisure, something to be used on weekends, a Mr. Marriott said in an interview. aNo one dreamed then of commuting to work by car.a The automobile was seen as way of escaping the tyranny of the railroad schedule, Mr. Marriott added. aIt was a way of interacting with nature.a

To finance the parkway, according to historical accounts, Vanderbilt and his associates raised $2 million from investors, some of whom thought the road would raise property values on the Gold Coast of Long Island. The roadas cost eventually rose to more than $6 million, and a $2 toll (about $45 today) was established. Regular patrons of the highway could buy a medallion good for a yearas passage.

Even the toll houses were worthy of a Vanderbilt: the first six were designed by the architect John Russell Pope, who also created the Jefferson Memorial and the Theodore Roosevelt Rotunda at the Museum of Natural History in New York. The toll takers and families lived in the houses, called lodges. One of these has been moved to Garden City, where it has been preserved and houses an exhibition on the history of the highway. Other lodges became homes.

The Long Island Motor Parkway did not solve the problem it was created to address. The race was run successfully enough on the new road in 1908 and 1909, but there were two fatal crashes in 1910, pretty much ending road races on Long Island.

Soon, traffic grew light on the road. In the Great Gatsby era of the 1920s bootleggers found the parkway a convenient linkbetween their delivery points on secluded beaches and the booming liquor market of Manhattan. The Vanderbilt Cup Race moved elsewhere, notably to Roosevelt Raceway in 1936 and 1937, when Ferdinand Porsche arrived to watch his Auto Union take first place.

By then, the public had access to cars as well. When Mr. Vanderbilt began, car owners were feared and resented in many areas, and speed limits were set as low as 5 m.p.h. Woodrow Wilson feared that popular irritation at rich motorists would be socially disruptive. aNothing has spread Socialistic feeling in this country more than the use of automobiles, a he declared in 1906 when he was president of Princeton University. aTo the countryman they are a picture of arrogance of wealth with all its independence and carelessness.a

But by the end of Vanderbiltas life (he died in 1944), the public had come to feel entitled to car ownership. And there was growing pressure for public highways, like the parkways that the urban planner Robert Moses was building.

In 1938, Moses refused Vanderbiltas appeal to incorporate the motor parkway into his new parkway system. The motor parkway just could not compete with the public roads, even after the toll was reduced to 40 cents, and Moses eventually gained control of Vanderbiltas pioneering road for back taxes of about $80,000. The day of public roads had come, supplanting private highways.

Today, the course of the road and a few ruined overpass bridges, guard rails and mileposts have been documented in books and Web sites, including VanderbiltCupRaces.com.

Part of the parkway and name survive as Suffolk County Road 67 (radio traffic reports still call the road the motorparkway). A small stretch was also incorporated into the Meadowbrook Parkway. But the best place to see remnants of the road is in Cunningham Park in Queens, where two of the 65 bridges that carried it over other roads remain. One is at 73rd Avenue and 99th Street. Another crosses Hollis Hills Terrace. Another original bridge crosses Springfield Boulevard. The old right of way is incorporated into the Brooklyn-Queens Greenway for bikers and walkers.

There is a certain irony that a road built for the most modern means of transportation is now being used for the oldest. The parkway marked the beginning of a process: the road was designed for the car. But in offering higher speeds, the parkway and other modern roads would push cars to their technical limits and beyond, inspiring innovation. In that sense, the first modern automobile highway helped to create the modern automobile.

Article Title: A 100-Year-Old Dream: A Road Just for Cars

Author: Phil Patton

Date: October 12th, 2008

It survives only as segments of other highways, as a right of way for power lines and as a bike trail, but the Long Island Motor Parkway still holds a sense of magic as what some historians say is the countryas first road built specifically for the automobile. It opened 100 years ago last Friday as a rich manas dream.

As detailed in a new book, aThe Long Island Motor Parkwaya by Howard Kroplick and Al Velocci (Arcadia Publishing), the parkway ran about 45 miles across Long Island, from Queens to Ronkonkoma, and was created by William Kissam Vanderbilt II, the great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt.

The younger Vanderbilt was a car enthusiast who loved to race. He had set a speed record of 92 miles an hour in 1904, the same year he created his own race, the Vanderbilt Cup.

But his race came under fire after a spectator was killed in 1906, and Vanderbilt wanted a safe road on which to hold the race and on which other car lovers could hurl their new machines free of the dust common on roads made for horses. The parkway would also be free of ainterference from the authorities, a he said in a speech.

So he created a toll road for high-speed automobile travel. It was built of reinforced concrete, had banked turns, guard rails and, by building bridges, he eliminated intersections that would slow a driver down. The Long Island Motor Parkway officially opened on Oct. 10, 1908, and closed in 1938.

Paul Daniel Marriott, a highway historian and consultant in Washington, said road designers began to take the carinto account around 1900. Like Vanderbilt, these early car owners were mostly wealthy men; they were called aautomobilistsa on the model of abicyclists.a

aCars were seen as objects for leisure, something to be used on weekends, a Mr. Marriott said in an interview. aNo one dreamed then of commuting to work by car.a The automobile was seen as way of escaping the tyranny of the railroad schedule, Mr. Marriott added. aIt was a way of interacting with nature.a

To finance the parkway, according to historical accounts, Vanderbilt and his associates raised $2 million from investors, some of whom thought the road would raise property values on the Gold Coast of Long Island. The roadas cost eventually rose to more than $6 million, and a $2 toll (about $45 today) was established. Regular patrons of the highway could buy a medallion good for a yearas passage.

Even the toll houses were worthy of a Vanderbilt: the first six were designed by the architect John Russell Pope, who also created the Jefferson Memorial and the Theodore Roosevelt Rotunda at the Museum of Natural History in New York. The toll takers and families lived in the houses, called lodges. One of these has been moved to Garden City, where it has been preserved and houses an exhibition on the history of the highway. Other lodges became homes.

The Long Island Motor Parkway did not solve the problem it was created to address. The race was run successfully enough on the new road in 1908 and 1909, but there were two fatal crashes in 1910, pretty much ending road races on Long Island.

Soon, traffic grew light on the road. In the Great Gatsby era of the 1920s bootleggers found the parkway a convenient linkbetween their delivery points on secluded beaches and the booming liquor market of Manhattan. The Vanderbilt Cup Race moved elsewhere, notably to Roosevelt Raceway in 1936 and 1937, when Ferdinand Porsche arrived to watch his Auto Union take first place.

By then, the public had access to cars as well. When Mr. Vanderbilt began, car owners were feared and resented in many areas, and speed limits were set as low as 5 m.p.h. Woodrow Wilson feared that popular irritation at rich motorists would be socially disruptive. aNothing has spread Socialistic feeling in this country more than the use of automobiles, a he declared in 1906 when he was president of Princeton University. aTo the countryman they are a picture of arrogance of wealth with all its independence and carelessness.a

But by the end of Vanderbiltas life (he died in 1944), the public had come to feel entitled to car ownership. And there was growing pressure for public highways, like the parkways that the urban planner Robert Moses was building.

In 1938, Moses refused Vanderbiltas appeal to incorporate the motor parkway into his new parkway system. The motor parkway just could not compete with the public roads, even after the toll was reduced to 40 cents, and Moses eventually gained control of Vanderbiltas pioneering road for back taxes of about $80,000. The day of public roads had come, supplanting private highways.

Today, the course of the road and a few ruined overpass bridges, guard rails and mileposts have been documented in books and Web sites, including VanderbiltCupRaces.com.

Part of the parkway and name survive as Suffolk County Road 67 (radio traffic reports still call the road the motorparkway). A small stretch was also incorporated into the Meadowbrook Parkway. But the best place to see remnants of the road is in Cunningham Park in Queens, where two of the 65 bridges that carried it over other roads remain. One is at 73rd Avenue and 99th Street. Another crosses Hollis Hills Terrace. Another original bridge crosses Springfield Boulevard. The old right of way is incorporated into the Brooklyn-Queens Greenway for bikers and walkers.

There is a certain irony that a road built for the most modern means of transportation is now being used for the oldest. The parkway marked the beginning of a process: the road was designed for the car. But in offering higher speeds, the parkway and other modern roads would push cars to their technical limits and beyond, inspiring innovation. In that sense, the first modern automobile highway helped to create the modern automobile.

Notă biografică

Howard Kroplick is the author of Vanderbilt Cup Races of Long Island. He is a lecturer, research volunteer at the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum, and member of the Vanderbilt Cup Race Centennial Committee and Long Island Motor Parkway Panel. Al Velocci is the author of The Toll Lodges of the Long Island Motor Parkway, and Their Gatekeepers Lives. He is also a research volunteer at the Suffolk County Vanderbilt Museum and a member of the Long Island Motor Parkway Panel.