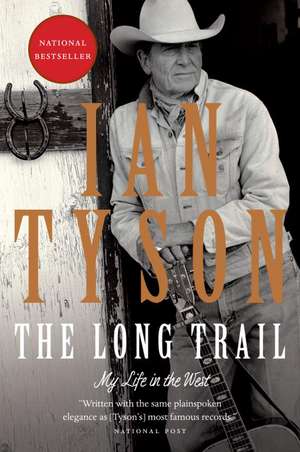

The Long Trail: My Life in the West

Autor Ian Tyson Jeremy Klaszusen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2011

"I live on a ranch about six miles east of the town of Longview and the old Cowboy Trail in the foothills of the Rockies. On a perfect day, like today, I can't imagine being anywhere else in the world. Of course, I'm not going to say there aren't those other days when you think, 'What am I doing here?' It's beautiful country and it can be brutally tough as well." —Ian Tyson

Ian Tyson's journey to the West began in the unlikely city of Victoria, BC, where he rode his dad's horses on the weekends and met cowboys in the pages of Will James's books, and eventually followed that cowboy dream to rodeo competition. Laid up after breaking a leg, he learned the guitar, and drifted east, becoming a key songwriter and performer in the folk revival movement. But the West always beckoned, and when his marriage to his partner and collaborator Sylvia broke up and the music scene threatened to grind him down, he retreated to a ranch and work with cutting horses. Soon, he'd bought a ranch in Alberta and found a new voice as the renowned Western Revival singer-songwriter and horseman he is today. This book is Ian's reflection on that journey...

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 105.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.15€ • 20.96$ • 16.63£

20.15€ • 20.96$ • 16.63£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307359360

ISBN-10: 0307359360

Pagini: 197

Ilustrații: B&W IMAGES THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 137 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

ISBN-10: 0307359360

Pagini: 197

Ilustrații: B&W IMAGES THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 137 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books Canada

Notă biografică

IAN TYSON has long been one of North America's most respected singer-songwriters. A pioneer who began his career in the folk boom of the '60s, he was one of the first Canadians to break into the American popular music market. In the years that followed, he hosted his own TV shows and recorded some of the best folk and western albums ever made. Tyson is a recipient of the Order of Canada, and has received multiple Juno and Canadian Country Music awards. He tours constantly across Canada and throughout the United States, and continues to live and work on his ranch in the foothills of Alberta's Rocky Mountains.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

Sunrise

It’s darker than three feet down a Holstein. Six a.m., Alberta daylight savings. Waking from a dream of Cabo San Lucas to a March north wind and five below. Everyone with half a brain and a Visa card has gotten out. Only us drones left to feed the livestock, so I make the coffee double strength and prepare to get at ’er. Fifteen minutes stumbling around on frozen manure should do it.

So begins the day.

Used to be a rancher wouldn’t divulge the size of his operation, nor the numbers of his herd. It’s a longstanding tradition in cow country that’s based on making as little information available to the tax people as possible. Suffice it to say, my outfit is a modest spread near the southern Alberta town of Longview, just east of the Rocky Mountain foothills.

During the ranch’s heyday in the 1990s, I ran between twenty and thirty horses. They were mostly mares, which meant there were lots of babies each year. That was back when my ex-wife Twylla and my daughter Adelita were still here. But they left a few years back, and these days it’s just me on the ranch — and only five horses to feed. There’s Bud, my cutting horse, a solid professional cowhorse, all business all the time. Then there’s Pokey, a bay mare, with all her feminine wiles, who loves to be the centre of attention. Every morning they’re lined up for their grain.

I feed my gentle grey mare and her half-broke daughter. The mare ran under the name Lika Pop back in her racetrack days and won her maiden at 350 yards. She’s eighteen now and crippled with a bad knee, but she’s been a good colt producer. Her daughter Doris is a big, pushy adolescent who’s never been properly schooled because I don’t have the time to do it. Finally there’s a new colt, a trim, good-moving two-year-old. He’s a blank canvas.

As for my two big longhorns, Kramer is laid back and Billy is more snuffy. While I pour their crushed barley into the rubber feed tub, their great horns sway slowly around my head in the darkness. I’m damn careful because I never know what Billy’s going to do. I bought Kramer and seven other yearling bulls in the mid-1990s from the late Mitford Beard, who ran one of the last American open-range outfits (no fences) on the Utah-Colorado line. Billy came a few years later, from rancher Bill Cross.

Billy and Kramer are my last two steers, and when it’s warm enough, they’ll wander out of their lot onto the prairie like a couple of old outlaws. Longhorns are like pets for ranchers, reminders of a bygone era when the trail herders drove cattle across the unfenced West. They’re almost conversation pieces nowadays.

Kramer sure gave me something to talk about when he got his horns stuck in a round-bale feeder a few years back. I heard all this banging coming from his pen, and when I went up to see what was going on, there was Kramer waving around this 200-pound bale feeder like a damn party hat, repeatedly crashing it into the fence. Those feeders aren’t small. They’re five feet across, with diagonal steel struts around the sides above the base. I guess he’d stuck his head and horns between the struts, right inside the feeder — he was more than happy to get closer to the hay. But when he wanted to get out, he couldn’t. Then the wreck was on.

I didn’t know what the hell to do. I called my neighbour Pete Wambeke, and he didn’t know what to do either. I couldn’t rope Kramer, because he’s too big and a horse couldn’t hold him. I considered getting some tranquilizers from the vet, but then I thought, I’m gonna take care of this myself. I got my hacksaw and approached Kramer warily, talking to him for almost half an hour before he finally let me stand beside him and start sawing away at the struts to free his horns.

I knew Kramer had only so much patience and then he’d lose it again and start waving his party hat around — he was already stepping on my feet. But he’s intelligent, and I guess he understood that I was going to get him out. I kept sawing, sweating like crazy. “Christ,” I muttered. “If I don’t have a cardiac arrest, it’s going to be a miracle.” Finally I got two struts cut and out he came, horns and all. He wandered off, thankful for his freedom.

Then the silly son of a bitch did the exact same thing the following year, and again I had to cut him free. After that I carefully eliminated all round-bale feeders from the longhorns’ pens.

—

After feeding the horses and longhorns in the early- morning dark, I give a few leftover wieners to the kitty-cats in the barn and head back inside for breakfast. I live in a cedar-log house built in 1975. That’s a big reason why I bought this land in 1979, when I was forty-six — I liked the rustic feel, as well as the huge basement. (The romance fades, however, when you realize that logs are great dust-catchers.) I also liked the big living room with its west-facing windows looking out on the shining mountains.

Today both the main floor and the basement are decorated with Navajo rugs, Mexican tile, eagle feathers, Indian artifacts and the western paintings, photos and horse sculptures I’ve collected over the years. In the kitchen hangs a framed poster from the inaugural 1961 Mariposa Folk Festival — a poster I designed — and there’s a brand new dishwasher, my pride and joy.

I’m a bacon freak, so I fry up some bacon, boil a couple of eggs and have a grapefruit before taking my vitamin pills. I also have to take naproxen and hyaluronic acid for my hands and wrists — old cowboys have lots of aches and pains, and I’ve been dealing with arthritis for the past twenty years. I keep my fingers limber by practising the guitar for at least an hour a day; otherwise my hands might shut down entirely.

Guitar practice is a daily discipline for me. I never was a night writer, never could pull a Hank Williams and stay up all night drinking whiskey and writing songs. In my world, mornings are for music and afternoons are spent doing the many chores that ranches require — moving hay bales, picking up feed in nearby Okotoks and making runs to the post office.

The only way to get any real writing done in the morning, though, is to get out of the home place and away from the phones. So after breakfast, at around 8 a.m., I pull on my hiking boots and begin the walk south down the gravel road to my stone house, where I do my songwriting.

On days like this one, towards the end of winter, the sun is often late rising above the clouds banked over the eastern plains. There’s no wind. The only sound is the faint humming of the power lines along the road, until the silence is broken by a raven calling as he heads for the mountains, and the distant burble of my neighbour’s truck with its busted muffler.

To the right is my hayfield, a great swath of buckskin grass delineated by thin snowdrifts along the fencelines. It was dry barley land when I first came here thirty years ago, and the black soil from that field blew like crazy. But when the rains came again, we seeded it all back to top-of-the-line grassland — the kind we need more of in this country. I’ve formed a loose partnership with my neighbour Pete to run grass yearlings from his outfit, the Diamond V, on the hayfield in May, and this summer will be no different.

Beyond the hayfield and high above the rolling foothills, the Rockies stay shrouded in grey until the sun’s first rays bathe the snow-covered peaks in rose pink and the timber foothills below in deep purple, a scene almost too theatrical to be real. I’ve seen the sunrise here a thousand times and it still moves me.

I arrive at the stone house after twenty minutes of walking. Built sometime in the 1920s, it has a green tin roof and sits on a wind-blasted little hill. The walls are sixteen inches thick. Originally I thought of it as a bunkhouse for itinerate punchers, but it soon became far more valuable as a music house. Now all my demos are done here — band rehearsals too. Guitars sound quite fine in the stone house in the morning, and lyrics are often found there soon after sunrise.

Before I enter, I walk to a treed area farther down the hill, where there’s a group of tilting shacks that comprised the original homestead on this land. Those first homesteaders ran sheep. I knocked most of the shacks down a few years back but kept a few for the animals, and I like to see who’s around in the morning. Owls keep a nest in the nearby willows, and deer sometimes yard up down there — it’s great hideaway country for them when the poplars leaf out. The occasional elk wanders in, and once I even saw a big old black bear nosing around the place, a rare sight on the bald prairie.

After visiting the animals — if the neighbour’s dog hasn’t scared them all away — I head into the stone house. Inside I’ve got a few couches, a couple of old rugs spread over hardwood floors and a big wooden table for writing. I make myself another coffee in the kitchen before getting out my guitar and running the scales, doing my best to warm up my stiff fingers. I slide a Mark Knopfler CD into my stereo system — I consider him my songwriting and guitar mentor, along with Ry Cooder — and try to keep up with him for a while before tackling my own material.

It’s been a long trail that brought me here. It all started September 25, 1933, on Vancouver Island — “west of the West,” as my friend, the photographer Jay Dusard, put it — where I grew up in the Oak Bay area of Victoria with my mom, dad and older sister, Jean. But my earliest childhood memories are mostly lost, thanks to too many miles and too many whiskey bottles. Too many years of trying to figure out who I was — and who I wanted to become.

From the Hardcover edition.

Sunrise

It’s darker than three feet down a Holstein. Six a.m., Alberta daylight savings. Waking from a dream of Cabo San Lucas to a March north wind and five below. Everyone with half a brain and a Visa card has gotten out. Only us drones left to feed the livestock, so I make the coffee double strength and prepare to get at ’er. Fifteen minutes stumbling around on frozen manure should do it.

So begins the day.

Used to be a rancher wouldn’t divulge the size of his operation, nor the numbers of his herd. It’s a longstanding tradition in cow country that’s based on making as little information available to the tax people as possible. Suffice it to say, my outfit is a modest spread near the southern Alberta town of Longview, just east of the Rocky Mountain foothills.

During the ranch’s heyday in the 1990s, I ran between twenty and thirty horses. They were mostly mares, which meant there were lots of babies each year. That was back when my ex-wife Twylla and my daughter Adelita were still here. But they left a few years back, and these days it’s just me on the ranch — and only five horses to feed. There’s Bud, my cutting horse, a solid professional cowhorse, all business all the time. Then there’s Pokey, a bay mare, with all her feminine wiles, who loves to be the centre of attention. Every morning they’re lined up for their grain.

I feed my gentle grey mare and her half-broke daughter. The mare ran under the name Lika Pop back in her racetrack days and won her maiden at 350 yards. She’s eighteen now and crippled with a bad knee, but she’s been a good colt producer. Her daughter Doris is a big, pushy adolescent who’s never been properly schooled because I don’t have the time to do it. Finally there’s a new colt, a trim, good-moving two-year-old. He’s a blank canvas.

As for my two big longhorns, Kramer is laid back and Billy is more snuffy. While I pour their crushed barley into the rubber feed tub, their great horns sway slowly around my head in the darkness. I’m damn careful because I never know what Billy’s going to do. I bought Kramer and seven other yearling bulls in the mid-1990s from the late Mitford Beard, who ran one of the last American open-range outfits (no fences) on the Utah-Colorado line. Billy came a few years later, from rancher Bill Cross.

Billy and Kramer are my last two steers, and when it’s warm enough, they’ll wander out of their lot onto the prairie like a couple of old outlaws. Longhorns are like pets for ranchers, reminders of a bygone era when the trail herders drove cattle across the unfenced West. They’re almost conversation pieces nowadays.

Kramer sure gave me something to talk about when he got his horns stuck in a round-bale feeder a few years back. I heard all this banging coming from his pen, and when I went up to see what was going on, there was Kramer waving around this 200-pound bale feeder like a damn party hat, repeatedly crashing it into the fence. Those feeders aren’t small. They’re five feet across, with diagonal steel struts around the sides above the base. I guess he’d stuck his head and horns between the struts, right inside the feeder — he was more than happy to get closer to the hay. But when he wanted to get out, he couldn’t. Then the wreck was on.

I didn’t know what the hell to do. I called my neighbour Pete Wambeke, and he didn’t know what to do either. I couldn’t rope Kramer, because he’s too big and a horse couldn’t hold him. I considered getting some tranquilizers from the vet, but then I thought, I’m gonna take care of this myself. I got my hacksaw and approached Kramer warily, talking to him for almost half an hour before he finally let me stand beside him and start sawing away at the struts to free his horns.

I knew Kramer had only so much patience and then he’d lose it again and start waving his party hat around — he was already stepping on my feet. But he’s intelligent, and I guess he understood that I was going to get him out. I kept sawing, sweating like crazy. “Christ,” I muttered. “If I don’t have a cardiac arrest, it’s going to be a miracle.” Finally I got two struts cut and out he came, horns and all. He wandered off, thankful for his freedom.

Then the silly son of a bitch did the exact same thing the following year, and again I had to cut him free. After that I carefully eliminated all round-bale feeders from the longhorns’ pens.

—

After feeding the horses and longhorns in the early- morning dark, I give a few leftover wieners to the kitty-cats in the barn and head back inside for breakfast. I live in a cedar-log house built in 1975. That’s a big reason why I bought this land in 1979, when I was forty-six — I liked the rustic feel, as well as the huge basement. (The romance fades, however, when you realize that logs are great dust-catchers.) I also liked the big living room with its west-facing windows looking out on the shining mountains.

Today both the main floor and the basement are decorated with Navajo rugs, Mexican tile, eagle feathers, Indian artifacts and the western paintings, photos and horse sculptures I’ve collected over the years. In the kitchen hangs a framed poster from the inaugural 1961 Mariposa Folk Festival — a poster I designed — and there’s a brand new dishwasher, my pride and joy.

I’m a bacon freak, so I fry up some bacon, boil a couple of eggs and have a grapefruit before taking my vitamin pills. I also have to take naproxen and hyaluronic acid for my hands and wrists — old cowboys have lots of aches and pains, and I’ve been dealing with arthritis for the past twenty years. I keep my fingers limber by practising the guitar for at least an hour a day; otherwise my hands might shut down entirely.

Guitar practice is a daily discipline for me. I never was a night writer, never could pull a Hank Williams and stay up all night drinking whiskey and writing songs. In my world, mornings are for music and afternoons are spent doing the many chores that ranches require — moving hay bales, picking up feed in nearby Okotoks and making runs to the post office.

The only way to get any real writing done in the morning, though, is to get out of the home place and away from the phones. So after breakfast, at around 8 a.m., I pull on my hiking boots and begin the walk south down the gravel road to my stone house, where I do my songwriting.

On days like this one, towards the end of winter, the sun is often late rising above the clouds banked over the eastern plains. There’s no wind. The only sound is the faint humming of the power lines along the road, until the silence is broken by a raven calling as he heads for the mountains, and the distant burble of my neighbour’s truck with its busted muffler.

To the right is my hayfield, a great swath of buckskin grass delineated by thin snowdrifts along the fencelines. It was dry barley land when I first came here thirty years ago, and the black soil from that field blew like crazy. But when the rains came again, we seeded it all back to top-of-the-line grassland — the kind we need more of in this country. I’ve formed a loose partnership with my neighbour Pete to run grass yearlings from his outfit, the Diamond V, on the hayfield in May, and this summer will be no different.

Beyond the hayfield and high above the rolling foothills, the Rockies stay shrouded in grey until the sun’s first rays bathe the snow-covered peaks in rose pink and the timber foothills below in deep purple, a scene almost too theatrical to be real. I’ve seen the sunrise here a thousand times and it still moves me.

I arrive at the stone house after twenty minutes of walking. Built sometime in the 1920s, it has a green tin roof and sits on a wind-blasted little hill. The walls are sixteen inches thick. Originally I thought of it as a bunkhouse for itinerate punchers, but it soon became far more valuable as a music house. Now all my demos are done here — band rehearsals too. Guitars sound quite fine in the stone house in the morning, and lyrics are often found there soon after sunrise.

Before I enter, I walk to a treed area farther down the hill, where there’s a group of tilting shacks that comprised the original homestead on this land. Those first homesteaders ran sheep. I knocked most of the shacks down a few years back but kept a few for the animals, and I like to see who’s around in the morning. Owls keep a nest in the nearby willows, and deer sometimes yard up down there — it’s great hideaway country for them when the poplars leaf out. The occasional elk wanders in, and once I even saw a big old black bear nosing around the place, a rare sight on the bald prairie.

After visiting the animals — if the neighbour’s dog hasn’t scared them all away — I head into the stone house. Inside I’ve got a few couches, a couple of old rugs spread over hardwood floors and a big wooden table for writing. I make myself another coffee in the kitchen before getting out my guitar and running the scales, doing my best to warm up my stiff fingers. I slide a Mark Knopfler CD into my stereo system — I consider him my songwriting and guitar mentor, along with Ry Cooder — and try to keep up with him for a while before tackling my own material.

It’s been a long trail that brought me here. It all started September 25, 1933, on Vancouver Island — “west of the West,” as my friend, the photographer Jay Dusard, put it — where I grew up in the Oak Bay area of Victoria with my mom, dad and older sister, Jean. But my earliest childhood memories are mostly lost, thanks to too many miles and too many whiskey bottles. Too many years of trying to figure out who I was — and who I wanted to become.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

NATIONAL BESTSELLER

“Tyson has had a long, fulfilling and interesting life. . . . He has become a tireless advocate for the protection of the western environment.”

— The Globe and Mail

“As Canadian living legends go, Ian Tyson rides tall in the saddle. [He] . . . spins an engaging tale.”

— Winnipeg Free Press

“Written with the same plainspoken elegance as [Tyson’s] most famous records. . . . Cool is something that comes effortlessly to Tyson.”

— National Post

From the Hardcover edition.

“Tyson has had a long, fulfilling and interesting life. . . . He has become a tireless advocate for the protection of the western environment.”

— The Globe and Mail

“As Canadian living legends go, Ian Tyson rides tall in the saddle. [He] . . . spins an engaging tale.”

— Winnipeg Free Press

“Written with the same plainspoken elegance as [Tyson’s] most famous records. . . . Cool is something that comes effortlessly to Tyson.”

— National Post

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

1. Sunrise

2. West of the West

3. Drifting

4. New York

5. Horses

6. Sagebrush Renaissance

7. Cowboyography

8. The Changing West

9. Beef, Beans and Bullshit

10. Raven Rock

11. Closing the Circle

From the Hardcover edition.

2. West of the West

3. Drifting

4. New York

5. Horses

6. Sagebrush Renaissance

7. Cowboyography

8. The Changing West

9. Beef, Beans and Bullshit

10. Raven Rock

11. Closing the Circle

From the Hardcover edition.