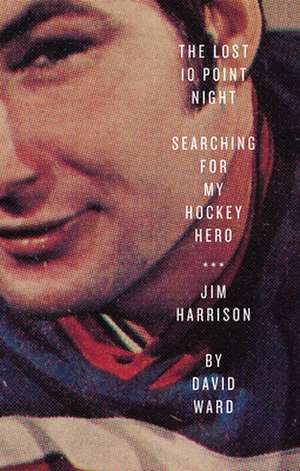

The Lost 10 Point Night: Searching for My Hockey Hero . . . Jim Harrison

Autor David Warden Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 sep 2014

Jim Harrison grew up on the prairies, played Junior in Saskatchewan, and pro with the Bruins, Leafs, Hawks, and Oilers. Three years before a former teammate equaled the mark, Harrison set one of the most enduring and seemingly unreachable records in professional hockey with three goals and seven helpers on January 30, 1973. And almost nobody remembers.

This is Harrison’s story: the games he played, the agent who stole from him, the woman he mourned, the fights he fought, and the friends he made — and lost — including Bobby Orr and Darryl Sittler. It’s about the injuries he suffered, the pedophiles who preyed on him and other young players, and a Players Association that, he says, “wants me to die.”

But The Lost 10 Point Night is also a response to Stephen Brunt’s Searching for Bobby Orr and Gretzky’s Tears — a book as much about Harrison as it is about author David Ward, a 50-year-old guy who went in search of his childhood hero . . . and what happened when they began looking at Canada’s game together.

This is Harrison’s story: the games he played, the agent who stole from him, the woman he mourned, the fights he fought, and the friends he made — and lost — including Bobby Orr and Darryl Sittler. It’s about the injuries he suffered, the pedophiles who preyed on him and other young players, and a Players Association that, he says, “wants me to die.”

But The Lost 10 Point Night is also a response to Stephen Brunt’s Searching for Bobby Orr and Gretzky’s Tears — a book as much about Harrison as it is about author David Ward, a 50-year-old guy who went in search of his childhood hero . . . and what happened when they began looking at Canada’s game together.

Preț: 94.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.07€ • 19.62$ • 15.18£

18.07€ • 19.62$ • 15.18£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781770411555

ISBN-10: 1770411550

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 155 x 224 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: ECW Press

ISBN-10: 1770411550

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 155 x 224 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: ECW Press

Recenzii

"The Lost 10 Point Night takes a look at the life of a player that took some odd twists over the years, and probably is more typical of athletes from that era than we might think. Those who have a personal connection to that time in hockey history will find this publication holds their interest nicely.” — Sports Book Review Center

"Overall, this is a solid book that I would recommend. It's a very easy book to read, and each individual story is kept short. I figured it was a book I'd pick up and read from time to time, but I ended up flying through it in one afternoon." — Order of Books

“The Lost 10 Point Night is a mixture of Harrison’s recollections, former teammates’ and coaches’ reflections on Harrison, and Ward’s own memories of Harrison from the 1970s. Not only does it paint a picture of a man who, though not a superstar, was an honest and respectable player, but also of the author’s connection to the subject as a fan . . . It is Ward’s contributions that make us understand why a third-line center from the 1970s is worthy of a book.” — Puck Junk

"Overall, this is a solid book that I would recommend. It's a very easy book to read, and each individual story is kept short. I figured it was a book I'd pick up and read from time to time, but I ended up flying through it in one afternoon." — Order of Books

“The Lost 10 Point Night is a mixture of Harrison’s recollections, former teammates’ and coaches’ reflections on Harrison, and Ward’s own memories of Harrison from the 1970s. Not only does it paint a picture of a man who, though not a superstar, was an honest and respectable player, but also of the author’s connection to the subject as a fan . . . It is Ward’s contributions that make us understand why a third-line center from the 1970s is worthy of a book.” — Puck Junk

Notă biografică

David Ward moves freely between his hometown of Kitchener, Ontario, and his adopted home of McCallum, Newfoundland. He is an author, teacher, columnist, and part-time lobster fisherman.

Extras

Chapter 15

When Jim’s hockey career came to a close with the NHL’s Chicago Black Hawks, I wasn’t paying attention. I’d suffered a huge loss earlier that year when my 26-year-old sister and her husband died in a car crash at Clappison’s Corners, in Ontario. A transport truck driver, heading north, fell asleep behind the wheel and crossed what in 1979 was a white center line.

My sister and brother-in-law, travelling south, didn’t stand a chance. I was at the family home in Kitchener when a good friend waiting for them in Hamilton called to say that my sister and her hubby hadn’t arrived. Given their responsible nature, enough time had elapsed since they had left their house that any hope their absence could be explained in a non-threatening way was no longer possible.

I called the police, and after a series of questions from them to clarify who I was and where we were, they simply said they would be at our home shortly. While I moved as quickly as I could toward denial, my parents knew better — Wendy and Robert were dead. I’ll never forget watching my mom in all her sadness and rage try to impart a physical beating on one of those big cops. She was obviously feeling pain that I, a childless male, will never be able to comprehend or describe with mere words.

Dad responded by going on an angry, 10-year alcoholic binge, making life miserable for my mother and little brother, who was only eight when the tragedy began. The rest of us, all young adults by then, bailed. To this day, I can’t imagine what life looked like to my mom, who, at 49, suddenly had a young child, a drunk, and a dead daughter and son-in-law to deal with for a decade. While not the same circumstance as Jim’s loss of Liz less than two decades later, my family found itself in a comparable crisis at a similar stage of life. So my last memories of Jim’s playing days are foggy. I don’t remember the tryout Glen Sather gave him with one of the NHL’s newest entries in Edmonton, after the NHL absorbed the Oilers and three other WHA teams, a merger that rendered the rebel league dead.

“I too don’t look back at that time fondly,” Jim says with a sigh. “Not only was my back not up for that Edmonton opportunity, but things hadn’t ended well in Chicago. Chicago was where the team doctor lied to me. That’s why now every player goes to his own doctor. Of course they do. Who the heck do you think is paying the team doctor? So now there are all these players with all this money — why wouldn’t they get another opinion?

“I had this sharp pain in my back that ran from my butt to my heel. So the Black Hawks team doctor injects something into me that he tells me will dissolve the parts of the disk in my back that are causing me so much pain. He calls the procedure an epidural block. But it turns out he didn’t give me an epidural block. He gave me a placebo — a shot of sugar — to see if I’m faking. It’s all right there in my medical records,” Jim says, pointing to a big box between us. “What did I do, dream up those operations? Put those scars on my back myself?”

Jim eases away from me for a moment. He’s far from done, so I suspect he is trying to collect some unresolved anger. “The next year, Rangers Dean Talafous cross-checks me and my leg goes numb,” he finally continues. “I tell the team doctor this. And I tell him that my coach, Bob Pulford — a former teammate of mine in Toronto — won’t give me any time to rest. Then the doctor tells Pulford what I said — that he’s a slave driver — and things with Pulford and me got really bad after that.

“Three days later I can’t move, so I take some Valium and climb into the whirlpool. Pulford comes along and asks me to play. I was the team’s tough guy, he tells me, and they needed me. I told him, ‘I can’t even walk,’ and he says, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’ He tells me to ‘Go rot in hell’ and then sends me to Moncton, where the Hawks’ farm team was. Pulford pissed on more players . . . Chicago is famous for that.

“I refused to go to Moncton, so Pulford suspends me without pay. Then I give Eagleson a call; he’d been my agent for six years. I figured we’d file a grievance. But Eagleson sends me to an old buddy of his, Dr. Bull, for a second opinion. Dr. Bull determined my most recent back operation resulted in nerve damage and that Talafous’ cross-check made it worse. Then, because I’m feeling like someone’s stuck a knife in me, Dr. Bull gives me some painkiller and tells me to rest. But I’m still not getting paid, so finally we file a grievance.

“Things got really complicated after that because my agent, Eagleson, was also Pulford’s agent. The two of them had been friends since childhood. Plus, Pulford was an employee of Hawks owner Bill Wirtz, and Wirtz and Eagleson were best buddies. Then John Ziegler was assigned to judge my grievance. Ziegler? He was the NHL president — that means Wirtz paid part of his salary. Got that? The guy reviewing my grievance was an employee of the organization I’d filed my grievance against. And the guy I’m paying to look out for me in all this was best buddies with the guys I’d officially complained about. He was even getting paid to act on behalf of one of them.

“By this point, Liz is livid. She’s driving me everywhere — I’ve got spasms so bad I’ve got to lie down in the back of our station wagon — and she can’t believe they can’t see how bad I’m hurting.”

Jim is full of emotion, moving around the room. I’m not sure if his actions are rooted in his love for Liz or his dislike for some of the other individuals he’s commenting on. “We were all told to go to a meeting — me, Liz, Eagleson, Pulford, Bobby [Orr, whose playing days were over and who was working as an assistant to Pulford], Dr. Kolb [Chicago’s team doctor], and Hawks trainer Skip Thayer. Keith Magnuson was supposed to be there. He was one of my teammates. He used to drive me to the rink, so I asked him to speak about how he had to lift my legs out of the car some days because I couldn’t do it myself, but he couldn’t make it to the meeting. The next year Chicago named him head coach. Suspicious, don’t you think?

“We were going into the room, and Eagleson told me Dr. Kolb and the trainers were against me, that he’d take care of everything, but that I wasn’t supposed to speak. Then Pulford said, ‘We’re sending him to Moncton. There’s nothing wrong with him.’ And Eagleson doesn’t ask any questions or tell them anything from our point of view. So I said, ‘I can’t believe what you guys are saying.’ Eagleson turns to me and yells, ‘I told you to shut up!’ Right in front of everybody. By this point I’m crying, I’m so angry. I yelled, ‘I can’t believe this! I can’t walk! And you guys think I’m faking!’

“After listening to what we all had to say, Ziegler tells everyone to leave the room except for Eagleson, Pulford, and Bobby, so they can make a ruling on my grievance. Half an hour later, Eagleson comes out and tells me I have to go to the minors. He just said, ‘That’s the rules if you want to get paid.’ So I went to the minors. What was I going to do? I had three kids to feed and bills to pay.

“Then,” says Jim, “I find out Ziegler didn’t really say I had to go to the minors. What he’d actually done was tell the Hawks that they hadn’t followed proper procedure. There are things you’ve got to do before you send a player down, and they hadn’t done them. As a result, all Ziegler was allowed to do was look at my grievance as a discussion. He couldn’t make a ruling on it. Sending me to the minors was something Eagleson and Pulford cooked up. Bobby confirmed it years later.”

Now it’s me that’s speechless. Did I hear that right — “Sending me to the minors was something Eagleson and Pulford cooked up”? But Jim’s got no time for my dumbfounded feelings — he is already recalling an ill-fated trip east. “So now I’m in the minors, in Moncton, New Brunswick. And things really begin to come off the tracks for me — that’s when I started mixing alcohol and pills. But it’s also in Moncton where I first convinced myself that my playing days were over. So I applied for disability insurance, and the insurance company told me to go to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. They wanted me to get a few more medical opinions, which was fine except the Hawks wouldn’t send them my medical records.

“The doctors in Minnesota said I’d need another operation. But no one would pay for it. No one would even pay the bills I was running up at the clinic. I had to pay ten grand out of my own pocket to cover expenses. You can hardly go ahead with an operation in the U.S. on those terms.

“So I asked Eagleson to draw up my retirement papers,” Jim explains. “He wrote that I wouldn’t be going after anyone with any lawsuits or medical claims. I was sitting in his office when I read this, and I told him I wouldn’t sign a letter like that, and he said, ‘You fucking hockey players think you’re something. Go get another lawyer.’ So that’s what I did. I went and got another

lawyer. But when Al found out, he threatened to throw my files on Bay Street if I didn’t get in right away to pick them up. So I went in and got them, and most of my things weren’t even in the box — including the letter we’d written asking for disability insurance.

“Then Eagleson told me that I couldn’t apply for Workers’ Compensation in Illinois, which was bullshit. After I did finally apply, I’d go to meetings and Wirtz’s lawyers wouldn’t show. I’d fly to Buffalo and when I got there, I’d wait around until someone told me that Wirtz’s lawyers had cancelled the meeting. The whole thing dragged on so long that Workers’ Comp eventually ruled I’d taken too long to apply so I no longer qualified.

“In the end, I got less than 10 percent of the $120,000 disability insurance I was entitled to. I could have fought harder but I needed the money and couldn’t tie it up in the system any longer.”

Jim, standing only two feet from me, looks me straight in the eyes. “That was just the beginning of my education — that was when I started to see what was going on between the league and Eagleson. That’s when guys began to wonder why Al wouldn’t allow for salary disclosure. He even told the guys who were playing at the time not to talk to the old-timers. But because Eagleson determined his own salary, he gave himself a $50,000-a-year pension when some of the game’s greatest stars were getting less than ten grand.

When Jim’s hockey career came to a close with the NHL’s Chicago Black Hawks, I wasn’t paying attention. I’d suffered a huge loss earlier that year when my 26-year-old sister and her husband died in a car crash at Clappison’s Corners, in Ontario. A transport truck driver, heading north, fell asleep behind the wheel and crossed what in 1979 was a white center line.

My sister and brother-in-law, travelling south, didn’t stand a chance. I was at the family home in Kitchener when a good friend waiting for them in Hamilton called to say that my sister and her hubby hadn’t arrived. Given their responsible nature, enough time had elapsed since they had left their house that any hope their absence could be explained in a non-threatening way was no longer possible.

I called the police, and after a series of questions from them to clarify who I was and where we were, they simply said they would be at our home shortly. While I moved as quickly as I could toward denial, my parents knew better — Wendy and Robert were dead. I’ll never forget watching my mom in all her sadness and rage try to impart a physical beating on one of those big cops. She was obviously feeling pain that I, a childless male, will never be able to comprehend or describe with mere words.

Dad responded by going on an angry, 10-year alcoholic binge, making life miserable for my mother and little brother, who was only eight when the tragedy began. The rest of us, all young adults by then, bailed. To this day, I can’t imagine what life looked like to my mom, who, at 49, suddenly had a young child, a drunk, and a dead daughter and son-in-law to deal with for a decade. While not the same circumstance as Jim’s loss of Liz less than two decades later, my family found itself in a comparable crisis at a similar stage of life. So my last memories of Jim’s playing days are foggy. I don’t remember the tryout Glen Sather gave him with one of the NHL’s newest entries in Edmonton, after the NHL absorbed the Oilers and three other WHA teams, a merger that rendered the rebel league dead.

“I too don’t look back at that time fondly,” Jim says with a sigh. “Not only was my back not up for that Edmonton opportunity, but things hadn’t ended well in Chicago. Chicago was where the team doctor lied to me. That’s why now every player goes to his own doctor. Of course they do. Who the heck do you think is paying the team doctor? So now there are all these players with all this money — why wouldn’t they get another opinion?

“I had this sharp pain in my back that ran from my butt to my heel. So the Black Hawks team doctor injects something into me that he tells me will dissolve the parts of the disk in my back that are causing me so much pain. He calls the procedure an epidural block. But it turns out he didn’t give me an epidural block. He gave me a placebo — a shot of sugar — to see if I’m faking. It’s all right there in my medical records,” Jim says, pointing to a big box between us. “What did I do, dream up those operations? Put those scars on my back myself?”

Jim eases away from me for a moment. He’s far from done, so I suspect he is trying to collect some unresolved anger. “The next year, Rangers Dean Talafous cross-checks me and my leg goes numb,” he finally continues. “I tell the team doctor this. And I tell him that my coach, Bob Pulford — a former teammate of mine in Toronto — won’t give me any time to rest. Then the doctor tells Pulford what I said — that he’s a slave driver — and things with Pulford and me got really bad after that.

“Three days later I can’t move, so I take some Valium and climb into the whirlpool. Pulford comes along and asks me to play. I was the team’s tough guy, he tells me, and they needed me. I told him, ‘I can’t even walk,’ and he says, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you.’ He tells me to ‘Go rot in hell’ and then sends me to Moncton, where the Hawks’ farm team was. Pulford pissed on more players . . . Chicago is famous for that.

“I refused to go to Moncton, so Pulford suspends me without pay. Then I give Eagleson a call; he’d been my agent for six years. I figured we’d file a grievance. But Eagleson sends me to an old buddy of his, Dr. Bull, for a second opinion. Dr. Bull determined my most recent back operation resulted in nerve damage and that Talafous’ cross-check made it worse. Then, because I’m feeling like someone’s stuck a knife in me, Dr. Bull gives me some painkiller and tells me to rest. But I’m still not getting paid, so finally we file a grievance.

“Things got really complicated after that because my agent, Eagleson, was also Pulford’s agent. The two of them had been friends since childhood. Plus, Pulford was an employee of Hawks owner Bill Wirtz, and Wirtz and Eagleson were best buddies. Then John Ziegler was assigned to judge my grievance. Ziegler? He was the NHL president — that means Wirtz paid part of his salary. Got that? The guy reviewing my grievance was an employee of the organization I’d filed my grievance against. And the guy I’m paying to look out for me in all this was best buddies with the guys I’d officially complained about. He was even getting paid to act on behalf of one of them.

“By this point, Liz is livid. She’s driving me everywhere — I’ve got spasms so bad I’ve got to lie down in the back of our station wagon — and she can’t believe they can’t see how bad I’m hurting.”

Jim is full of emotion, moving around the room. I’m not sure if his actions are rooted in his love for Liz or his dislike for some of the other individuals he’s commenting on. “We were all told to go to a meeting — me, Liz, Eagleson, Pulford, Bobby [Orr, whose playing days were over and who was working as an assistant to Pulford], Dr. Kolb [Chicago’s team doctor], and Hawks trainer Skip Thayer. Keith Magnuson was supposed to be there. He was one of my teammates. He used to drive me to the rink, so I asked him to speak about how he had to lift my legs out of the car some days because I couldn’t do it myself, but he couldn’t make it to the meeting. The next year Chicago named him head coach. Suspicious, don’t you think?

“We were going into the room, and Eagleson told me Dr. Kolb and the trainers were against me, that he’d take care of everything, but that I wasn’t supposed to speak. Then Pulford said, ‘We’re sending him to Moncton. There’s nothing wrong with him.’ And Eagleson doesn’t ask any questions or tell them anything from our point of view. So I said, ‘I can’t believe what you guys are saying.’ Eagleson turns to me and yells, ‘I told you to shut up!’ Right in front of everybody. By this point I’m crying, I’m so angry. I yelled, ‘I can’t believe this! I can’t walk! And you guys think I’m faking!’

“After listening to what we all had to say, Ziegler tells everyone to leave the room except for Eagleson, Pulford, and Bobby, so they can make a ruling on my grievance. Half an hour later, Eagleson comes out and tells me I have to go to the minors. He just said, ‘That’s the rules if you want to get paid.’ So I went to the minors. What was I going to do? I had three kids to feed and bills to pay.

“Then,” says Jim, “I find out Ziegler didn’t really say I had to go to the minors. What he’d actually done was tell the Hawks that they hadn’t followed proper procedure. There are things you’ve got to do before you send a player down, and they hadn’t done them. As a result, all Ziegler was allowed to do was look at my grievance as a discussion. He couldn’t make a ruling on it. Sending me to the minors was something Eagleson and Pulford cooked up. Bobby confirmed it years later.”

Now it’s me that’s speechless. Did I hear that right — “Sending me to the minors was something Eagleson and Pulford cooked up”? But Jim’s got no time for my dumbfounded feelings — he is already recalling an ill-fated trip east. “So now I’m in the minors, in Moncton, New Brunswick. And things really begin to come off the tracks for me — that’s when I started mixing alcohol and pills. But it’s also in Moncton where I first convinced myself that my playing days were over. So I applied for disability insurance, and the insurance company told me to go to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. They wanted me to get a few more medical opinions, which was fine except the Hawks wouldn’t send them my medical records.

“The doctors in Minnesota said I’d need another operation. But no one would pay for it. No one would even pay the bills I was running up at the clinic. I had to pay ten grand out of my own pocket to cover expenses. You can hardly go ahead with an operation in the U.S. on those terms.

“So I asked Eagleson to draw up my retirement papers,” Jim explains. “He wrote that I wouldn’t be going after anyone with any lawsuits or medical claims. I was sitting in his office when I read this, and I told him I wouldn’t sign a letter like that, and he said, ‘You fucking hockey players think you’re something. Go get another lawyer.’ So that’s what I did. I went and got another

lawyer. But when Al found out, he threatened to throw my files on Bay Street if I didn’t get in right away to pick them up. So I went in and got them, and most of my things weren’t even in the box — including the letter we’d written asking for disability insurance.

“Then Eagleson told me that I couldn’t apply for Workers’ Compensation in Illinois, which was bullshit. After I did finally apply, I’d go to meetings and Wirtz’s lawyers wouldn’t show. I’d fly to Buffalo and when I got there, I’d wait around until someone told me that Wirtz’s lawyers had cancelled the meeting. The whole thing dragged on so long that Workers’ Comp eventually ruled I’d taken too long to apply so I no longer qualified.

“In the end, I got less than 10 percent of the $120,000 disability insurance I was entitled to. I could have fought harder but I needed the money and couldn’t tie it up in the system any longer.”

Jim, standing only two feet from me, looks me straight in the eyes. “That was just the beginning of my education — that was when I started to see what was going on between the league and Eagleson. That’s when guys began to wonder why Al wouldn’t allow for salary disclosure. He even told the guys who were playing at the time not to talk to the old-timers. But because Eagleson determined his own salary, he gave himself a $50,000-a-year pension when some of the game’s greatest stars were getting less than ten grand.