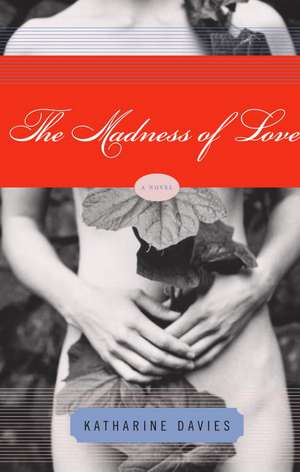

The Madness of Love

Autor Katharine Daviesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 2005

Valentina, a clerk in a London bookstore, is still reeling after her twin brother broke a childhood promise and ran off without her to exotic lands. When she cuts her hair, masquerades as a gardener to the melancholic Leo, and moves to the remote seaside town of Illerwick, she perplexes even herself.

Leo dreams of restoring his estate’s gardens to their former glory as a romantically naïve gesture toward the woman he’s loved all his life: Melody, an English teacher whose beauty bewitches many others. Melody rejects any attempt at capture; she is locked in a state of mourning over the suicide of her dear brother.

As Valentina struggles with the decades-old neglect of flowers, plants, and weeds, her affection for her eccentric employer grows, even as she helps him plot his overture to Melody. The gardens must be made ready for a grand late-summer party. But between now and then, Illerwick will stir with old longings and new desires. As people fall dangerously for those incapable of reciprocating, we see, enchantingly, how our misguided pursuit of passion often distracts us from finding real love.

Preț: 77.83 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 117

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.91€ • 15.36$ • 12.49£

14.91€ • 15.36$ • 12.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812973280

ISBN-10: 0812973283

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 145 x 218 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Random House

ISBN-10: 0812973283

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 145 x 218 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Random House

Notă biografică

KATHARINE DAVIES grew up in Warwickshire and studied English and drama at the University of London. She taught English for several years, including a period in Sri Lanka, before receiving an M.A. in creative writing. The Madness of Love is her first novel, and she is currently at work on her second.

Extras

1

Melody

He walked into the wind, his back to the inland sky, oblivious of the snow that was at that moment about to fall and that then fell on Illerwick. He looked only outward, across the waves, ignoring the yellow eyes of the sheep that lined his way and lifted their heads to watch his passing. His hands swung bravely by his sides, as in a march. At the end of the headland he stopped and allowed the wind to sweep away all his thoughts. He listened to the sea’s slow breaths and echoed them with his own and this calmed him. There was a boom, far below, like a drumroll. The seagulls cried in encouragement. He crouched down, his thighs taut, his bitten nails buried in the wet grass. There was not a false start. He took a run at it, toward the air. He did not keep running, cartoonishly, only to hover and look down in fear. He executed a perfect dive and fell, like a stone, into immediate nothing.

This is what Melody imagined afterward, when they told her what had happened to Gabriel. She thought, It’s what he would have wanted.

2

Fitch

Miss Vye was standing with her back to the window when Fitch and the others came in. The great height of the window made her look smaller than she really was. Outside, the snow made the light bright. It hurt Fitch’s eyes to look at Miss Vye against that particular light but when he closed them her miniature silhouette was tattooed on the inside of his eyelids. He opened them. He couldn’t see the expression on her face. He wondered if she had only just turned around or if she had been watching him in line as he came in from the playground. She moved to the blackboard, smoothing her dress over her hips, and was tall again. She seemed to be studying something on her desk as she waited for them to grow calm. The noise of voices lessened as she started to take the register silently, her sea-green eyes flicking up to each face, her lips moving slightly as she said their names under her breath. He watched her teeth release her lower lip on the whispered “F” of his name. His heart was beating. He said her name inside his head: Melody.

The class was quieter than usual, exhausted by the snow. Miss Vye looked at the class and into Fitch’s eyes but he looked down, his face burning. The talking stopped; they had known her for four years so no one could be bothered to disobey her. She seemed about to speak but then she turned to the blackboard. Fitch felt relief wash over him. He pressed his forehead down onto the pile of books on his desk. When he looked up he felt dazed. He saw that his head had left a greasy, heart-shaped stain on the front of his English book. He turned it over. A ruler was digging into his arm. Suzy passed him a square of paper folded about a million times but he knew what it said without reading it. He ate it. A question was appearing on the board in Miss Vye’s italic hand. Miss Vye sneezed as she always did when she wrote on the blackboard and the sneeze made her forget the question mark but there was no doubt that what she had written was a question. It was about the madness of love in the play and it contained the word “topsy-turvydom.” It was now up to them to answer the question. Miss Vye was writing some instructions. Fitch read the words over and over again but they seemed to make no sense. He put up his hand.

“Yes?” She smiled at him. It was the last time she would smile for weeks but no one knew that yet.

“Miss Vye . . .” He forgot what he wanted to ask. He went red. There were some titters.

Dave’s voice came from the back of the class: “You’ve forgotten the question mark, Miss.”

Miss Vye added the question mark without saying anything. Fitch could see Dave’s face smirking without needing to look. Dave’s parents ran the newsagent’s and he thought friendship could be bought in exchange for sweets.

Everyone else had started. The clock got louder. Fat Pete farted twice. But outside it had started to snow again and Fitch found it hard not to look out of the window at the whiteness, hard not to just sit and watch the accretion of snow on the trees. Suzy sighed dreamily, her squat letters filling the lines. Fitch wrote the title at the top of the page, then he wrote the date, January 5, in the margin in the left-hand corner. He started with a quotation. Miss Vye always told them to weave quotations into their sentences. Miss Vye said his writing was spidery. He tried to disguise its spideriness by making it italic but it only got more spidery. He looked up. Miss Vye seemed to be staring at him. She began to walk up the narrow aisle between the desks toward him, glancing at the essays in other people’s books as she came. She bent over his desk and a coil of her flame-colored hair fell against his ear. He had an erection. She moved away. A gritting lorry was rumbling down the road and a man called Leo Spring, who was going to start teaching him the piano soon, was walking past the school railings wearing a Russian hat. Leo Spring’s face turned once, quickly and blindly, in the direction of the classroom and then stared fixedly ahead but Miss Vye had suddenly dropped her book and was at that moment bending down to pick it up so she didn’t see him. She went back to her desk on the side of the room farthest from the window, sidestepping her way around Pete’s broad back.

Fitch became absorbed in his essay. He had written one and a half pages of his exercise book and woven in eighteen quotations when there was a knock at the door. He stopped writing. A few people almost stood up as Mr. Boase, the deputy headmaster, edged into the room but he gestured for them to sit. He went and whispered something in the ear of Miss Vye. She made a small noise in the back of her throat. No one was writing now. They watched her go pale. She started to gather the papers from her desk but Mr. Boase put a restraining hand on her arm. She left the papers. She turned away and faced the wall. Mr. Boase put his arm briefly around her shoulder. Fitch hated him; anyone else would have spoken to her outside. Miss Vye picked up her handbag and ran out.

Suzy looked at Fitch with wide eyes. The room began to fill with whispers but not the laughing kind. Mr. Boase sidled to the front of the teacher’s desk and said, “Right!” but he had no presence. People had abandoned their essays now. Pete and Dave were leaning back in their chairs listening amicably to the girls in the row in front. The sound of voices was getting louder and when Suzy offered to collect the books, since it was only five minutes until home time, Mr. Boase said, “Very well.” Fitch saw that his book was on the top but now he wondered if Miss Vye would ever mark them. The bell rang and most of the others barged out. He left Suzy in the classroom trying to wheedle out of Mr. Boase what was wrong with Miss Vye. He didn’t speak to anyone. He lingered in the corridor. Mr. Boase would not tell her. He waited in the boys’ cloakroom so that Suzy would think he’d gone. He didn’t speak to anyone. The snow was falling faster and a group of boys was running up the playing field hurling snowballs. He turned sharply left out of the school gates and walked along Broad Street past a boy in the year below who asked him if he was going sledding down Bryn Mawr.

He said, “Maybe later.”

He kept walking. He knew where he was going. He had traveled this distance in his dreams for weeks. He crossed the river. It looked black and shiny in the fading light. He was only wearing his blazer but the snow just seemed to tickle him. He felt exhilarated. The tune of a film he had watched the night before swooped through his mind. When he got to Miss Vye’s house it was in darkness. There were no tracks that he could see. He leaned against her front door. Everything was silent because of the snow. He saw a light through the trees. He went toward it. He walked through the snow, through the woods, along the edges of fields and crept into a garden. It was like a garden in a dream. He looked in at the windows of the house of Leo Spring. Leo Spring was sitting in a red velvet armchair smoking. He looked as though he might be listening to music. He stubbed out his cigarette and put his head, with the Russian hat still on it, in his hands. His body started to rock backward and forward. A terrible sobbing noise reached Fitch through the glass. He ran all the way home, snow soaking through his school shoes.

Melody

He walked into the wind, his back to the inland sky, oblivious of the snow that was at that moment about to fall and that then fell on Illerwick. He looked only outward, across the waves, ignoring the yellow eyes of the sheep that lined his way and lifted their heads to watch his passing. His hands swung bravely by his sides, as in a march. At the end of the headland he stopped and allowed the wind to sweep away all his thoughts. He listened to the sea’s slow breaths and echoed them with his own and this calmed him. There was a boom, far below, like a drumroll. The seagulls cried in encouragement. He crouched down, his thighs taut, his bitten nails buried in the wet grass. There was not a false start. He took a run at it, toward the air. He did not keep running, cartoonishly, only to hover and look down in fear. He executed a perfect dive and fell, like a stone, into immediate nothing.

This is what Melody imagined afterward, when they told her what had happened to Gabriel. She thought, It’s what he would have wanted.

2

Fitch

Miss Vye was standing with her back to the window when Fitch and the others came in. The great height of the window made her look smaller than she really was. Outside, the snow made the light bright. It hurt Fitch’s eyes to look at Miss Vye against that particular light but when he closed them her miniature silhouette was tattooed on the inside of his eyelids. He opened them. He couldn’t see the expression on her face. He wondered if she had only just turned around or if she had been watching him in line as he came in from the playground. She moved to the blackboard, smoothing her dress over her hips, and was tall again. She seemed to be studying something on her desk as she waited for them to grow calm. The noise of voices lessened as she started to take the register silently, her sea-green eyes flicking up to each face, her lips moving slightly as she said their names under her breath. He watched her teeth release her lower lip on the whispered “F” of his name. His heart was beating. He said her name inside his head: Melody.

The class was quieter than usual, exhausted by the snow. Miss Vye looked at the class and into Fitch’s eyes but he looked down, his face burning. The talking stopped; they had known her for four years so no one could be bothered to disobey her. She seemed about to speak but then she turned to the blackboard. Fitch felt relief wash over him. He pressed his forehead down onto the pile of books on his desk. When he looked up he felt dazed. He saw that his head had left a greasy, heart-shaped stain on the front of his English book. He turned it over. A ruler was digging into his arm. Suzy passed him a square of paper folded about a million times but he knew what it said without reading it. He ate it. A question was appearing on the board in Miss Vye’s italic hand. Miss Vye sneezed as she always did when she wrote on the blackboard and the sneeze made her forget the question mark but there was no doubt that what she had written was a question. It was about the madness of love in the play and it contained the word “topsy-turvydom.” It was now up to them to answer the question. Miss Vye was writing some instructions. Fitch read the words over and over again but they seemed to make no sense. He put up his hand.

“Yes?” She smiled at him. It was the last time she would smile for weeks but no one knew that yet.

“Miss Vye . . .” He forgot what he wanted to ask. He went red. There were some titters.

Dave’s voice came from the back of the class: “You’ve forgotten the question mark, Miss.”

Miss Vye added the question mark without saying anything. Fitch could see Dave’s face smirking without needing to look. Dave’s parents ran the newsagent’s and he thought friendship could be bought in exchange for sweets.

Everyone else had started. The clock got louder. Fat Pete farted twice. But outside it had started to snow again and Fitch found it hard not to look out of the window at the whiteness, hard not to just sit and watch the accretion of snow on the trees. Suzy sighed dreamily, her squat letters filling the lines. Fitch wrote the title at the top of the page, then he wrote the date, January 5, in the margin in the left-hand corner. He started with a quotation. Miss Vye always told them to weave quotations into their sentences. Miss Vye said his writing was spidery. He tried to disguise its spideriness by making it italic but it only got more spidery. He looked up. Miss Vye seemed to be staring at him. She began to walk up the narrow aisle between the desks toward him, glancing at the essays in other people’s books as she came. She bent over his desk and a coil of her flame-colored hair fell against his ear. He had an erection. She moved away. A gritting lorry was rumbling down the road and a man called Leo Spring, who was going to start teaching him the piano soon, was walking past the school railings wearing a Russian hat. Leo Spring’s face turned once, quickly and blindly, in the direction of the classroom and then stared fixedly ahead but Miss Vye had suddenly dropped her book and was at that moment bending down to pick it up so she didn’t see him. She went back to her desk on the side of the room farthest from the window, sidestepping her way around Pete’s broad back.

Fitch became absorbed in his essay. He had written one and a half pages of his exercise book and woven in eighteen quotations when there was a knock at the door. He stopped writing. A few people almost stood up as Mr. Boase, the deputy headmaster, edged into the room but he gestured for them to sit. He went and whispered something in the ear of Miss Vye. She made a small noise in the back of her throat. No one was writing now. They watched her go pale. She started to gather the papers from her desk but Mr. Boase put a restraining hand on her arm. She left the papers. She turned away and faced the wall. Mr. Boase put his arm briefly around her shoulder. Fitch hated him; anyone else would have spoken to her outside. Miss Vye picked up her handbag and ran out.

Suzy looked at Fitch with wide eyes. The room began to fill with whispers but not the laughing kind. Mr. Boase sidled to the front of the teacher’s desk and said, “Right!” but he had no presence. People had abandoned their essays now. Pete and Dave were leaning back in their chairs listening amicably to the girls in the row in front. The sound of voices was getting louder and when Suzy offered to collect the books, since it was only five minutes until home time, Mr. Boase said, “Very well.” Fitch saw that his book was on the top but now he wondered if Miss Vye would ever mark them. The bell rang and most of the others barged out. He left Suzy in the classroom trying to wheedle out of Mr. Boase what was wrong with Miss Vye. He didn’t speak to anyone. He lingered in the corridor. Mr. Boase would not tell her. He waited in the boys’ cloakroom so that Suzy would think he’d gone. He didn’t speak to anyone. The snow was falling faster and a group of boys was running up the playing field hurling snowballs. He turned sharply left out of the school gates and walked along Broad Street past a boy in the year below who asked him if he was going sledding down Bryn Mawr.

He said, “Maybe later.”

He kept walking. He knew where he was going. He had traveled this distance in his dreams for weeks. He crossed the river. It looked black and shiny in the fading light. He was only wearing his blazer but the snow just seemed to tickle him. He felt exhilarated. The tune of a film he had watched the night before swooped through his mind. When he got to Miss Vye’s house it was in darkness. There were no tracks that he could see. He leaned against her front door. Everything was silent because of the snow. He saw a light through the trees. He went toward it. He walked through the snow, through the woods, along the edges of fields and crept into a garden. It was like a garden in a dream. He looked in at the windows of the house of Leo Spring. Leo Spring was sitting in a red velvet armchair smoking. He looked as though he might be listening to music. He stubbed out his cigarette and put his head, with the Russian hat still on it, in his hands. His body started to rock backward and forward. A terrible sobbing noise reached Fitch through the glass. He ran all the way home, snow soaking through his school shoes.

Recenzii

Advance praise for The Madness of Love

“Davies has written a wonderful first novel about the lives of star-crossed lovers whose foibles and failings and mad, mad hearts stir up equal doses of trouble and passion. The Madness of Love is a lush tragicomic tale that is satisfying, smart, and oh-so-spicy.”

–Connie May Fowler, author of The Problem with Murmur Lee and Before Women Had Wings

“Quirky characters, real passion, and a jaw-dropping masquerade–what more could a reader ask for? Davies’s first novel is funny and heartbreaking by turns, a clever, modern take on Shakespeare, and the perfect introduction to a talented new writer.”

–Darin Strauss, author of Chang and Eng and The Real McCoy

Praise in England for The Madness of Love

“Davies plays with the plot of Twelfth Night, changing it as it suits her. . . . The artifice of the whole conceit, this dextrous shifting between the plausible and implausible, is what gives [The Madness of Love] its hallucinatory quality; its texture of changeable taffeta.”

–The Independent

“Davies is a very promising writer with an eye for a good image, and with the ability to cast a disturbing air of enchantment over proceedings.”

–The Guardian

“[The Madness of Love] turns upon a genuine tragedy, but tinged with enchantment. . . . [Davies has] a light, confident touch, and exquisite pacing.”

–The Observer

"Davies admirably conjures up the wild beauty of Illerwick's coastal landscape . . . [and] what does come across rather well is a wistful sense of the end of youth." --Literary Review