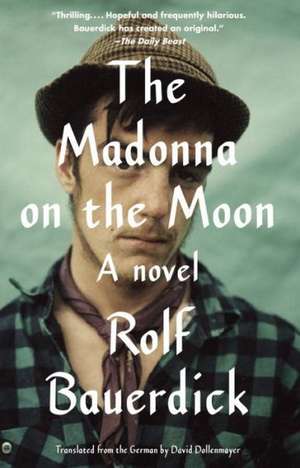

The Madonna on the Moon

Autor Rolf Bauerdicken Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2014

November 1957: As Communism spreads across Eastern Europe, strange events are beginning to upend daily life in Baia Luna, a tiny village nestled at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains. As the Soviets race to reach the moon and Sputnik soars overhead, fifteen-year-old Pavel Botev attends the small village school with the other children. Their sole teacher, the mysterious and once beautiful Angela Barbulescu, was sent by the Ministry of Education, and while it is suspected that she has lived a highly cultured life, much of her past remains hidden. But one day, after asking Pavel to help hang a photo of the new party secretary, she whispers a startling directive in his ear: “Send this man straight to hell! Exterminate him!” By the next morning, she has disappeared.

With little more to go on than the gossip and rumors swirling through his grandfather Ilja’s tavern, Pavel finds curiosity overcoming his fear when suddenly the village’s sacred Madonna statue is stolen and the priest Johannes Baptiste is found brutally murdered in the rectory. Aided by the Gypsy girl Buba and her eccentric uncle, Dimitru Gabor, Pavel’s search for answers leads him far from the innocent concerns of childhood and into the frontiers of a new world, changing his life forever.

Preț: 94.86 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.15€ • 19.78$ • 15.30£

18.15€ • 19.78$ • 15.30£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307739759

ISBN-10: 0307739759

Pagini: 401

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Colecția Vintage Books

ISBN-10: 0307739759

Pagini: 401

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Colecția Vintage Books

Notă biografică

Rolf Bauerdick was born in 1957. He studied literature and theology before turning to journalism and photography. His work has received numerous awards, among them Germany’s prestigious Hansel Mieth Prize. His articles have been published in Der Spiegel, GEO, and Playboy, among other publications. He lives in a converted flour mill in Northern Germany with his wife and children. The Madonna on the Moon is his first novel.

Translated from the German by David Dollenmayer.

Translated from the German by David Dollenmayer.

Extras

Chapter One

Baia Luna, New York, and Angela Barbulescu’s Fear

“He’s flying! He’s flying! Long live Socialism! Three cheers for the party!”

The three Brancusi brothers, Liviu, Roman, and Nico, burst into our taproom one evening about eight in a splendid mood, their chests swelling with pride and the cash to stand a few rounds burn- ing holes in their pockets.

“Who’s flying?” asked my grandfather Ilja.

“The dog of course! Laika! The first animal in space! Aboard Sputnik II! Brandy, Pavel! Zuika for everybody! But avanti! It’s on us.” Liviu was playing the big shot, and I could foresee I’d have to run myself ragged the next few hours.

“Gr-gr-gr-gravity has been co-co-conquered! Now nothing can hold back pr-pr-progress. Sp-Sputnik beeps and Laika b-barks all around the w-w-world,” Roman stammered, as he always did when his tongue couldn’t keep up with his excitement.

“Progress, yes sir,” Nico, the youngest Brancusi, fell in with his stammering brother. “A toast to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics! Side by side we will be victorious! We will conquer the heavens!”

“You can keep your schnapps to yourselves.” The Saxons Hermann Schuster and Karl Koch threw on their coats and left the taproom.

Trouble hung in the air that November 5, 1957. It was a Tuesday and the eve of my grandfather Ilja’s fifty-fifth birthday. I was fifteen. In the mornings I reluctantly attended the eighth (and final) grade, in the afternoons I killed time, and evenings and Sundays I helped my grandfather, waiting on his clientele in our family’s tavern. I should mention that it wasn’t an inn in the ordinary sense of the word. Ilja, my mother Kathalina, and Aunt Antonia ran a shop by day whose inventory provided the housewives of Baia Luna with the basic necessities. By night, we moved a few tables and chairs into the shop and transformed it into a pub for the men.

All I understood of the Brancusis’ blabber about progress was that a dog was zooming across the sky in a beeping Sputnik that managed to do without jet engines and rotating propellers and had nothing in common with ordinary airplanes. At the price, however, of never being able to return to earth. Satellites had escaped the rules of gravity and were on their way to eternal flight in space.

While the men in the bar were getting hot under the collar discussing the whys and wherefores of the newfangled airships, my grandfather Ilja was unmoved: “Weightlessness—not bad. My compliments. But the Russian beeping won’t fill my belly.”

Dimitru Carolea Gabor stood up and took the floor. Some of the men lowered their chins in contempt. After all, didn’t people say the Gypsy had his feet in the clouds and thought with his tongue? Dimitru clutched his right fist to his heart as if taking an oath. He stood there like a rock and swore that the chirping flying contraption was the work of the Supreme Comrade of all Comrades, Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin himself. While still alive, he’d ordered a whole armada of Sputniks to be built. “Sly machines camouflaged as harmless balls of tin, under way on secret missions, and now they even have a dog onboard. I don’t quite get the point of that yapper among the stars, but I’ll tell you something: those aluminum spiders aren’t poking their antennae into the sky just for fun. The Supreme Soviet has something up its sleeve. That beeping, that cosmic cicada, robs peaceful human beings of their sleep and of their sanity, too. And you know what that means? If you’re crazy, you turn into a zombie, and the world revolution just goose-steps right past you. And then, comrades”—Dimitru stared at the three Brancusis—“then you’ve finally achieved the equality of the entire proletariat. The idiot among equals thinks everyone’s smart.”

“In your case, the beeping seems to be working already.” Liviu tapped his finger on his forehead to mock the crazy Gypsy. “You Blacks are nothing to write home about, anyway. Why don’t you do something productive for a change? Under Stalin, you all would’ve been—”

“Right! Exactamente! What’d I tell you?” Dimitru interrupted him. “Joseph was a sly dog. But he had problems getting every- one proletarianized. Big problems. Because his policy of state control just couldn’t achieve the equality of all the Soviets. Sure, the Supreme Comrade really tried hard: bigger jails, higher prison walls, bread and water, half rations. He tried to rub out the last vestiges of inequality with more and more gallows and firing squads. But what did that achieve? Joseph had to keep expanding the labor camps for the unequal. The boundaries of the prisons grew incalculably vast. Today no one knows who’s in and who’s out. What a dilemma. The Supreme Soviet can’t keep track of it all anymore. That’s why they need Sputnik. The beeping eliminates the mind and the will. And where there’s no will, there’s no—”

“Who needs this bullshit?” yelled Nico Brancusi. Purple with rage, he jumped up and glared around at the assembled company. “Who wants to hear this crap, goddamnit!” From way back in his throat he hocked up a loogie and spat it onto the floorboards with the words, “Gypsy lies! Black talk!”

Dimitru drummed his fingers nervously on the table.

“It’s the truth,” he said. “If my calculations are correct, Sputnik will be flying over the Transmontanian Carpathians between the forty-sixth degree of latitude and the twenty-fourth degree of longitude in the morning hours of my friend Ilja’s special day. It’ll be beeping right over our heads. I’m telling you, Sputnik is the beginning of the end. And you, Comrade Nico, you can offer your naked ass to whoever you want, that’s your business. But I’m a Gypsy, and you’ll never find a Gypsy in bed with the Bolsheviks.”

Nico went for the Gypsy’s throat, but his brothers held him back. Dimitru emptied his glass, belched, and after whispering to grandfather, “Five on the dot. I’ll be waiting for you,” left the tavern without a backward glance.

I didn’t know what to think about all the excitement. I went to bed but had a hard time falling asleep. The Gypsy had probably catapulted himself out of the track of logical thought again (as so often in the past) with his hair-raising speculations about the beeping Sputnik.

But my bedtime prayer (which admittedly I usually forgot) suddenly gave me pause. “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come . . .” Now, at fifteen, I was already clear that the kingdom of heaven was not about to arrive in the foreseeable future, at least not in Baia Luna. But it was different with the Sputnik. The kingdom of heaven might not be expanding on earth, but on the other hand, man was heading for the heavens. Or at least an earthly creature was: a dog. Surely the beast would soon be dead of starvation. But what was a dead mutt doing in the infinity of space anyway? Up where the Lord God and his hosts reigned, as our aged parish priest Johannes Baptiste thundered from his pulpit every Sunday.

Night was already drawing to a close when the floorboards in the hall creaked. I heard cautious footsteps, as if someone didn’t want to be heard. Grandfather was taking great pains not to wake up my mother Kathalina, Aunt Antonia, and me. The footsteps descended the stairs and died out in the interior of the shop. I waited awhile, got dressed, and stole downstairs, full of curiosity. The outside door was open. It was pitch black.

“Fucking shit,” hissed a voice. “Goddamn crappy weather!” It was Dimitru.

“Be quiet or you’ll wake up the whole village.”

“I prayed, Ilja, I mean I really beseeched the Creator to make short work of it and with one puff of his almighty breath sweep away these goddamn clouds. And what does he do when just once a Gypsy asks for something? He sends us this fog from hell. We can forget about hearing the Sputnik in this pea soup.”

I hid behind the doorjamb and peered outside. Dimitru was right. It had been raining buckets for days, and now the fog had crept down from the mountains. You couldn’t even see the outline of the church steeple. Five muffled strokes of the clock penetrated the night. Ilja and Dimitru looked up at the sky. They cocked their heads, put their hands behind their ears, and listened again. Obviously in vain. Disappointed, the two shuffled back into the shop. They didn’t see me.

“Ilja, I’m wondering if it wouldn’t make sense to go back to bed for a while,” said Dimitru.

“It does make sense.”

Then the Gypsy’s gaze fell on the tin funnel my grandfather always used to pour the sunflower oil delivered in canisters from Walachia into the bottles the village housewives brought.

“Man, Ilja, that’s it! Your funnel. We’ll use it as a megaphone, only in reverse. You’ve heard of the principle of the concentration of sound waves—sonatus concentrates or something like that? We can use it to capture even the faintest hint of a noise.”

The two went back outside and took turns sticking the tin funnel first into their left ear and then their right, hoping to amplify the sound. For a good quarter of an hour they swiveled their heads in all directions.

When at last I cleared my throat and wished them good morning, they gave it up.

“So, Dimitru, you’re going to let Sputnik steal your sanity?” I ribbed him.

“Go ahead and laugh, Pavel. Blessed are those who neither see nor hear but still believe. Let me assure you, it’s beeping. Evidentamente. We just can’t hear it.”

“No wonder,” I pretended to be sympathetic. “The November fog. It swallows everything up and you can’t hear a thing. Not the calves bleating, not even the cocks crowing. To say nothing of Sputnik, it’s so far away. Beyond the pull of gravity, if I’ve got it right.”

“Good thinking, Pavel! You’re right, when it’s foggy the Sputnik’s not worth much. The Supreme Comrade didn’t think of that. Between you and me and in the cold light of day, Stalin was pretty much of an idiot. But don’t spread it around. That can get you into trouble nowadays. And now, forgive me, but my bed is calling.”

Grandfather looked a little sheepish. It made him self-conscious to be caught holding a funnel to his ear out in front of the shop on his fifty-fifth birthday.

“Pavel, go with Dimitru so he doesn’t break his neck on the way home. You can’t see your hand in front of your face.”

Out of sorts, I groped my way with Dimitru to the lower end of the village where his people lived. At the doorstep of his cottage he put his hand to his ear again and listened.

“Give it up, Dimitru. What’s the point?”

“Sic est. You’re right,” he said, thanked me for my company, and disappeared inside.

Was it mere coincidence? No idea. But just as I set off back through the village, the roosters began to crow, and across from the Gypsy settlement a weak light shimmered through the fog. For the second time on that early morning I let myself be driven by curiosity. The light was shining from the cottage of Angela Barbulescu, the village schoolteacher. This early in the morning! “Barbu,” as we called her, usually slept till all hours. She seldom showed up for class on time, and once in front of the class, she often stared at us from swollen eyes because the brandy from the previous evening was still having its effect. I left the street and peeked through her window. She was sitting at the kitchen table with a warm wool blanket thrown over her shoulders. Incredible! She was sitting there writing something. She lifted her head from time to time and looked at the ceiling as if seeking the right word. Much more than the fact that Barbu was apparently getting something important down on paper at this ungodly hour, it was her face I found astonishing. In the last few years of school, I had come to think she was disgusting. I never looked at her except with contempt, if not revulsion.

Yet the Barbu I saw early on the morning of November 6, 1957, was different. She was bright and clear. Beautiful, even. Someday in the not-too-distant future I would understand what was happening in Angela Barbulescu’s cottage that morning, and it would plunge me into the abyss. But how could I have known it in that dreary November dawn?

Baia Luna, New York, and Angela Barbulescu’s Fear

“He’s flying! He’s flying! Long live Socialism! Three cheers for the party!”

The three Brancusi brothers, Liviu, Roman, and Nico, burst into our taproom one evening about eight in a splendid mood, their chests swelling with pride and the cash to stand a few rounds burn- ing holes in their pockets.

“Who’s flying?” asked my grandfather Ilja.

“The dog of course! Laika! The first animal in space! Aboard Sputnik II! Brandy, Pavel! Zuika for everybody! But avanti! It’s on us.” Liviu was playing the big shot, and I could foresee I’d have to run myself ragged the next few hours.

“Gr-gr-gr-gravity has been co-co-conquered! Now nothing can hold back pr-pr-progress. Sp-Sputnik beeps and Laika b-barks all around the w-w-world,” Roman stammered, as he always did when his tongue couldn’t keep up with his excitement.

“Progress, yes sir,” Nico, the youngest Brancusi, fell in with his stammering brother. “A toast to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics! Side by side we will be victorious! We will conquer the heavens!”

“You can keep your schnapps to yourselves.” The Saxons Hermann Schuster and Karl Koch threw on their coats and left the taproom.

Trouble hung in the air that November 5, 1957. It was a Tuesday and the eve of my grandfather Ilja’s fifty-fifth birthday. I was fifteen. In the mornings I reluctantly attended the eighth (and final) grade, in the afternoons I killed time, and evenings and Sundays I helped my grandfather, waiting on his clientele in our family’s tavern. I should mention that it wasn’t an inn in the ordinary sense of the word. Ilja, my mother Kathalina, and Aunt Antonia ran a shop by day whose inventory provided the housewives of Baia Luna with the basic necessities. By night, we moved a few tables and chairs into the shop and transformed it into a pub for the men.

All I understood of the Brancusis’ blabber about progress was that a dog was zooming across the sky in a beeping Sputnik that managed to do without jet engines and rotating propellers and had nothing in common with ordinary airplanes. At the price, however, of never being able to return to earth. Satellites had escaped the rules of gravity and were on their way to eternal flight in space.

While the men in the bar were getting hot under the collar discussing the whys and wherefores of the newfangled airships, my grandfather Ilja was unmoved: “Weightlessness—not bad. My compliments. But the Russian beeping won’t fill my belly.”

Dimitru Carolea Gabor stood up and took the floor. Some of the men lowered their chins in contempt. After all, didn’t people say the Gypsy had his feet in the clouds and thought with his tongue? Dimitru clutched his right fist to his heart as if taking an oath. He stood there like a rock and swore that the chirping flying contraption was the work of the Supreme Comrade of all Comrades, Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin himself. While still alive, he’d ordered a whole armada of Sputniks to be built. “Sly machines camouflaged as harmless balls of tin, under way on secret missions, and now they even have a dog onboard. I don’t quite get the point of that yapper among the stars, but I’ll tell you something: those aluminum spiders aren’t poking their antennae into the sky just for fun. The Supreme Soviet has something up its sleeve. That beeping, that cosmic cicada, robs peaceful human beings of their sleep and of their sanity, too. And you know what that means? If you’re crazy, you turn into a zombie, and the world revolution just goose-steps right past you. And then, comrades”—Dimitru stared at the three Brancusis—“then you’ve finally achieved the equality of the entire proletariat. The idiot among equals thinks everyone’s smart.”

“In your case, the beeping seems to be working already.” Liviu tapped his finger on his forehead to mock the crazy Gypsy. “You Blacks are nothing to write home about, anyway. Why don’t you do something productive for a change? Under Stalin, you all would’ve been—”

“Right! Exactamente! What’d I tell you?” Dimitru interrupted him. “Joseph was a sly dog. But he had problems getting every- one proletarianized. Big problems. Because his policy of state control just couldn’t achieve the equality of all the Soviets. Sure, the Supreme Comrade really tried hard: bigger jails, higher prison walls, bread and water, half rations. He tried to rub out the last vestiges of inequality with more and more gallows and firing squads. But what did that achieve? Joseph had to keep expanding the labor camps for the unequal. The boundaries of the prisons grew incalculably vast. Today no one knows who’s in and who’s out. What a dilemma. The Supreme Soviet can’t keep track of it all anymore. That’s why they need Sputnik. The beeping eliminates the mind and the will. And where there’s no will, there’s no—”

“Who needs this bullshit?” yelled Nico Brancusi. Purple with rage, he jumped up and glared around at the assembled company. “Who wants to hear this crap, goddamnit!” From way back in his throat he hocked up a loogie and spat it onto the floorboards with the words, “Gypsy lies! Black talk!”

Dimitru drummed his fingers nervously on the table.

“It’s the truth,” he said. “If my calculations are correct, Sputnik will be flying over the Transmontanian Carpathians between the forty-sixth degree of latitude and the twenty-fourth degree of longitude in the morning hours of my friend Ilja’s special day. It’ll be beeping right over our heads. I’m telling you, Sputnik is the beginning of the end. And you, Comrade Nico, you can offer your naked ass to whoever you want, that’s your business. But I’m a Gypsy, and you’ll never find a Gypsy in bed with the Bolsheviks.”

Nico went for the Gypsy’s throat, but his brothers held him back. Dimitru emptied his glass, belched, and after whispering to grandfather, “Five on the dot. I’ll be waiting for you,” left the tavern without a backward glance.

I didn’t know what to think about all the excitement. I went to bed but had a hard time falling asleep. The Gypsy had probably catapulted himself out of the track of logical thought again (as so often in the past) with his hair-raising speculations about the beeping Sputnik.

But my bedtime prayer (which admittedly I usually forgot) suddenly gave me pause. “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come . . .” Now, at fifteen, I was already clear that the kingdom of heaven was not about to arrive in the foreseeable future, at least not in Baia Luna. But it was different with the Sputnik. The kingdom of heaven might not be expanding on earth, but on the other hand, man was heading for the heavens. Or at least an earthly creature was: a dog. Surely the beast would soon be dead of starvation. But what was a dead mutt doing in the infinity of space anyway? Up where the Lord God and his hosts reigned, as our aged parish priest Johannes Baptiste thundered from his pulpit every Sunday.

Night was already drawing to a close when the floorboards in the hall creaked. I heard cautious footsteps, as if someone didn’t want to be heard. Grandfather was taking great pains not to wake up my mother Kathalina, Aunt Antonia, and me. The footsteps descended the stairs and died out in the interior of the shop. I waited awhile, got dressed, and stole downstairs, full of curiosity. The outside door was open. It was pitch black.

“Fucking shit,” hissed a voice. “Goddamn crappy weather!” It was Dimitru.

“Be quiet or you’ll wake up the whole village.”

“I prayed, Ilja, I mean I really beseeched the Creator to make short work of it and with one puff of his almighty breath sweep away these goddamn clouds. And what does he do when just once a Gypsy asks for something? He sends us this fog from hell. We can forget about hearing the Sputnik in this pea soup.”

I hid behind the doorjamb and peered outside. Dimitru was right. It had been raining buckets for days, and now the fog had crept down from the mountains. You couldn’t even see the outline of the church steeple. Five muffled strokes of the clock penetrated the night. Ilja and Dimitru looked up at the sky. They cocked their heads, put their hands behind their ears, and listened again. Obviously in vain. Disappointed, the two shuffled back into the shop. They didn’t see me.

“Ilja, I’m wondering if it wouldn’t make sense to go back to bed for a while,” said Dimitru.

“It does make sense.”

Then the Gypsy’s gaze fell on the tin funnel my grandfather always used to pour the sunflower oil delivered in canisters from Walachia into the bottles the village housewives brought.

“Man, Ilja, that’s it! Your funnel. We’ll use it as a megaphone, only in reverse. You’ve heard of the principle of the concentration of sound waves—sonatus concentrates or something like that? We can use it to capture even the faintest hint of a noise.”

The two went back outside and took turns sticking the tin funnel first into their left ear and then their right, hoping to amplify the sound. For a good quarter of an hour they swiveled their heads in all directions.

When at last I cleared my throat and wished them good morning, they gave it up.

“So, Dimitru, you’re going to let Sputnik steal your sanity?” I ribbed him.

“Go ahead and laugh, Pavel. Blessed are those who neither see nor hear but still believe. Let me assure you, it’s beeping. Evidentamente. We just can’t hear it.”

“No wonder,” I pretended to be sympathetic. “The November fog. It swallows everything up and you can’t hear a thing. Not the calves bleating, not even the cocks crowing. To say nothing of Sputnik, it’s so far away. Beyond the pull of gravity, if I’ve got it right.”

“Good thinking, Pavel! You’re right, when it’s foggy the Sputnik’s not worth much. The Supreme Comrade didn’t think of that. Between you and me and in the cold light of day, Stalin was pretty much of an idiot. But don’t spread it around. That can get you into trouble nowadays. And now, forgive me, but my bed is calling.”

Grandfather looked a little sheepish. It made him self-conscious to be caught holding a funnel to his ear out in front of the shop on his fifty-fifth birthday.

“Pavel, go with Dimitru so he doesn’t break his neck on the way home. You can’t see your hand in front of your face.”

Out of sorts, I groped my way with Dimitru to the lower end of the village where his people lived. At the doorstep of his cottage he put his hand to his ear again and listened.

“Give it up, Dimitru. What’s the point?”

“Sic est. You’re right,” he said, thanked me for my company, and disappeared inside.

Was it mere coincidence? No idea. But just as I set off back through the village, the roosters began to crow, and across from the Gypsy settlement a weak light shimmered through the fog. For the second time on that early morning I let myself be driven by curiosity. The light was shining from the cottage of Angela Barbulescu, the village schoolteacher. This early in the morning! “Barbu,” as we called her, usually slept till all hours. She seldom showed up for class on time, and once in front of the class, she often stared at us from swollen eyes because the brandy from the previous evening was still having its effect. I left the street and peeked through her window. She was sitting at the kitchen table with a warm wool blanket thrown over her shoulders. Incredible! She was sitting there writing something. She lifted her head from time to time and looked at the ceiling as if seeking the right word. Much more than the fact that Barbu was apparently getting something important down on paper at this ungodly hour, it was her face I found astonishing. In the last few years of school, I had come to think she was disgusting. I never looked at her except with contempt, if not revulsion.

Yet the Barbu I saw early on the morning of November 6, 1957, was different. She was bright and clear. Beautiful, even. Someday in the not-too-distant future I would understand what was happening in Angela Barbulescu’s cottage that morning, and it would plunge me into the abyss. But how could I have known it in that dreary November dawn?

Recenzii

“The Madonna on the Moon is a hopeful and frequently hilarious story of using one’s courage, patience, and wits to stand up against oppression. Weaving folklore, political drama, a coming-of-age story, and a morality tale together, Bauerdick has created an original.” ߝThe Daily Beast

International Praise for Rolf Bauerdick’s The Madonna on the Moon

“Rolf Bauerdick is a natural-born storyteller. The fierce realism of his story spoils neither its magic nor its humor.” ߝSpiegel Online

“A dazzling book, larger than life, exuberantly picturesque . . . . German literature has a powerful new voice—and most of all an unusual one.” ߝFocus

“Bizarre and anarchistic, The Madonna on the Moon is enormously entertaining.” ߝDie Welt

International Praise for Rolf Bauerdick’s The Madonna on the Moon

“Rolf Bauerdick is a natural-born storyteller. The fierce realism of his story spoils neither its magic nor its humor.” ߝSpiegel Online

“A dazzling book, larger than life, exuberantly picturesque . . . . German literature has a powerful new voice—and most of all an unusual one.” ߝFocus

“Bizarre and anarchistic, The Madonna on the Moon is enormously entertaining.” ߝDie Welt