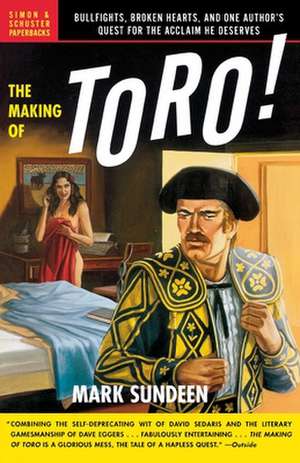

The Making of Toro: Bullfights, Broken Hearts, and One Author's Quest for the Acclaim He Deserves

Autor Mark Sundeenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 mai 2004

After squandering most of the book advance, Sundeen can't afford a trip to Spain, so he settles for nearby Mexico. But the bullfighting he finds there is tawdry and comical, and there's little of the passion and bravery that he'd hoped to employ in exhibiting his literary genius to the masses.

To compensate for his own shortcomings as an author, Sundeen invents an alter ego, Travis LaFrance, a swashbuckling adventure writer in the tradition of Sundeen's idol, Ernest Hemingway. When LaFrance steps in, our narrator goes blundering through the landscape of his own dreams and delusions, propelled solely by the preposterous insistence that his own life story, no matter how crummy, is worth being told in the pages of Great Literature.

The Making of Toro is a unique comic classic and a sly, poignant tale of the hazards of trying too hard to turn real life into high art.

Preț: 83.15 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 125

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.91€ • 16.65$ • 13.24£

15.91€ • 16.65$ • 13.24£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743255639

ISBN-10: 0743255631

Pagini: 192

Ilustrații: 7 b&w photos t-o

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:04000

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 0743255631

Pagini: 192

Ilustrații: 7 b&w photos t-o

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:04000

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Mark Sundeen is the author of Car Camping and lives in Utah.

Extras

Chapter One

The news that I was to write a book about bullfighting came after a morning spent emptying tubs of human poo. You might think that in this age of talking toasters and the programmable toothbrush, science would provide a machine for this chore, but no: My only tools were gravity, scrub brush, and a garden hose. The plastic tubs were white and heavy like little ovens, cooking with the waste of twenty-five people who had just rafted for a week down the Colorado River. Beneath the seat was an opening big enough to insert your head, and on the ground where the poo had to go was a hole no wider than my fist.

Before becoming the author of an excellent but overlooked adventure book, I had considered this work filthy and dehumanizing -- beneath me, actually -- and I would have demanded that the guides clean it themselves. But events in the last year had changed my opinion. Under the name of Travis LaFrance I'd published a slim paperback about hunting for desert rodents with highly trained falcons, a brilliant little book really, not at all about birds if you could read between the lines but rather a deft song of the self in the guise of a swashbuckling how-to. Fun with Falconry is triumphant, soaked in the sauce of boyish lyricism but fried tough in a cynic's skillet. I recommend it.

But so convincing was my book of meta-falconry that the literati could not crack its facade. "Unfortunately there is no plot," wrote one newsman, a dim observation he'll regret until some merciful downsizing at headquarters ends his ill-chosen career. Meanwhile, the book flew over the heads of the bird-of-prey trade magazines, and despite my dreams of seeing Travis LaFrance leaning against Jack London on the Literature shelf, Fun with Falconry was exiled by booksellers to the Animal Husbandry alcove, doomed to obscurity alongside Tricks for Turtles and An Introduction to Llama Packing.

So instead of spending the summer rubbing my chin on book shows and rubbing the knees of ripe coeds who would endure around-the-block waits for an autograph -- instead of that, I had returned to my honorable job in the hot Utah desert and was currently faced with the prospect of moving poo from a plastic tub to a hole in the ground. I'd taken this job with the promise that I'd be rowing boats by the end of the season, but three years later I'd proven so indispensable around the yard that the boss couldn't afford to lend me to the river.

Luckily literature had paid me in a spiritual currency more rare than job advancement. "My art is my life, and versa vice," says Falconry's stoic hero, and adopting Travis LaFrance's creed as my own, I had discovered the virtuosity of poo disposal. Since the book's publication I had even begun volunteering to do it, a development that had not only fortified my character but delighted my co-workers, who were too simple to understand me.

There is a relatively sanitary method to the task. By fastening a tube you can drain the box into the sewage hold without ever seeing its contents. But I had forsworn this tube as a cowardly apparatus. I wanted to be more like Travis LaFrance, who instead of wincing at destiny grabs it bare-handed and molds it into something beautiful.

My method was pure, expressive, a triumph of both form and function. I set the box on the concrete pad, kicked it once to its side, kicked it twice upside down, then lifted. The box had been topped off with water earlier in the day to loosen the clumps, and now with a great sucking sound there erupted a terrific mountain of shit and toilet paper and tampons and maggots, spilling green rivulets of septic chemical down its ravines. Some of my co-workers, like rubes in a fine art gallery, simply can't fathom the beauty: They gasp, they gag, they cover their eyes. But I looked on calmly. With my discriminating eye I saw a robust palette of raw tempera awaiting the infusion of human spirit.

"Jimbo," I called, as he happened to walk by. "Have you seen The Scepter?"

"You mean that nasty broom handle?"

"I mean The Scepter."

"In the Dumpster, where it belongs."

It was 100 degrees and I was sweating in my rubber boots and plastic apron and elbow-length dishwasher gloves. Though sometimes the poo is sufficiently soft to be gulped up by the hole in a single prolonged swallow, today as usual we had a clog. I had left The Scepter here in my studio for these occasions, but some unenlightened simp had apparently tossed it. Sifting through the garbage I retrieved the slender oaken staff, gripped it tightly so that our spirits might mingle, and then like Jackson Pollack stirring his bucket I plunged it forcefully through the shit heap. It was just the thing. The heap coughed, I aimed the hose, and then with a spit and a sublime gurgle the poo was slurped into the earth.

A good morning's work. I rinsed the boxes, slapping to dislodge the lonely corn kernel, then bleached the units and set them to dry. I peeled off my protective layers and washed. Saying good-bye to the guides still busy with such pedestrian tasks as washing pots and scrubbing coolers, I pitied for a moment their artless lives, then drove home to my trailer. Catching a whiff of sewage, I sniffed myself and checked my shoe soles, but didn't find any residue.

Before I reached the shower I discovered the message from New York concerning a book. Don't think I'm some hack who lets the latest glossy gazette charter me a camel ride or spelunking tour. I am an artist. Whereas young men in other generations have measured their courage by enemy gunfire, my imagined crucible concerned that inevitable million-dollar offer: Would I stand true to my craft and refuse it or would I sign on the line and go to hell with the rest of the sellouts? So before making the phone call I scrubbed to the elbows for the third time and resolved to accept no work that would demean me.

The agent and I had never met. He was a voice on the line who reported now and then that, like the work of any misunderstood visionary, my writing had not sold. My records showed that he'd earned $64.57 from our arrangement the previous year, and I imagined him at lunch in a fancy bar and grill boasting to all the other agents about the satisfaction of representing a true master. "I used to value money like you do," he'd scold them, "but that was before I found a higher calling." The other agents would sulk back to their plush offices feeling at once the hollowness of their riches and a new inspiration to exalt literature to the people.

And now things were turning around, said the agent when his assistant finally took me off hold and patched me through. A publisher wanted to pay me to write a book.

"A book about what?"

"Bullfighting."

I had never been to a bullfight.

"Are we talking six figures?" I said.

"Not quite."

"High fives?"

"Nope."

"Medium fives?"

"Upper fours," said the agent.

I did not figure that minus the agent's cut my total payment for Toro would be about seven thousand dollars. My mind computes moods, not numbers. I did not consider how much it would cost to get to the part of the world that has bullfights and live there long enough to write a book, and I certainly did not calculate how quickly I could earn that same sum in the boatyard. In a flicker of fantasy I saw the name Travis LaFrance emblazoned on another book jacket, topping the critics' top-ten lists, headlining the program for the White House reception. The more I considered a winter in Moab collecting unemployment and applying for heat assistance, the more I realized that, yes, what literature really needs at this moment is a book about bullfighting by a young white American man, and that accepting such a small advance would not be the soulless money grab of a sellout, but on the contrary would constitute proof that my work transcended monetary value. Without a hesitation I said:

"I'll do it."

The result, once I iron out a few wrinkles with the publisher, will be Toro: Encounters with Men and Bulls: An Aficionado's Odyssey from Tijuana to Mexico City and Back. Its phenomenal success will astound everyone but me. By the time you read this, Toro will have already had a long surf atop the bestseller charts, Travis LaFrance will be a talk-show staple, and critics will have talked themselves hoarse pronouncing him the next Ernest Hemingway.

Since you're reading The Making of Toro, you've surely read Toro and want to learn about the man behind Travis. If not, you'll pop down to your bookseller, where stacks of LaFrance are disappearing by the crateload, but for now a bit of background will help. Here's the proposal I wrote after the phone call from the agent, which with a few minor edits will grace the bestselling dust jacket.

Ernest Hemingway. Pablo Picasso.

Great artists and great men, united by a passion for fine women, high adventure, and la fiesta brava. In Toro: Encounters with Men and Bulls: An Aficionado's Odyssey from Tijuana to Madrid, falconer Travis LaFrance takes us on a voyage through the 21st-century remnants of the Spanish empire, in search of the flickering flame of manhood imported from Iberia five centuries ago.

His quest begins in Tijuana, the northernmost outpost of the Kingdom of Carlos, where the blood of the bulls mingles with the sweat of the laborer on his journey toward el norte. Making his way by train, burro, and thumb through the dusty villages, lured by cold cerveza and strong tequila and lusty señoritas, the ever-hardy LaFrance blends the drama and artistry of the bullring with his rich tales of love and loss, and reveals that, yes, beyond that familiar realm of the starched-shirt pencil-pushers, in a land more primitive and passionate than his own, there does yet exist a small yet robust sample of that endangered species known as man.

Toro pierces the heart of la fiesta brava, the soul of Mexico and Spain, and not least of all the spirit of Travis LaFrance.

A month has passed since I shipped the finished manuscript of Toro, and the publisher's silence has been like that of a stunned bullring after a flawless kill. But I won't postpone my victory lap waiting for those New York judges to wave a green handkerchief. No matter how great the book is, no one will read it if they don't hear about it, and I vowed early that Toro would not slip into the same cracks that held Fun with Falconry. Having seen television shows like "The Making of Titanic," I know that a blockbuster is not the work of some recluse behind a typewriter, but the result of slick marketing that hypes the final product as so fabulous that it merits a documentary on its very creation. What works for movies should work for books, and so as I set out to write Toro I also began this behind-the-scenes memoir of the forging of a classic. Call it a companion piece to genius.

So join me, reader, and learn how an average soul like myself has invented a legend. Do not be dismayed to learn that, like you, I am imperfect and fallible. Do not be disappointed that I am not the man whom you have come to admire and envy. Rather, as we study the evolution of our hero, take heart that even I, his creator, strive each day to be a bit more like Travis LaFrance.

Copyright © 2003 by Mark Sundeen

The news that I was to write a book about bullfighting came after a morning spent emptying tubs of human poo. You might think that in this age of talking toasters and the programmable toothbrush, science would provide a machine for this chore, but no: My only tools were gravity, scrub brush, and a garden hose. The plastic tubs were white and heavy like little ovens, cooking with the waste of twenty-five people who had just rafted for a week down the Colorado River. Beneath the seat was an opening big enough to insert your head, and on the ground where the poo had to go was a hole no wider than my fist.

Before becoming the author of an excellent but overlooked adventure book, I had considered this work filthy and dehumanizing -- beneath me, actually -- and I would have demanded that the guides clean it themselves. But events in the last year had changed my opinion. Under the name of Travis LaFrance I'd published a slim paperback about hunting for desert rodents with highly trained falcons, a brilliant little book really, not at all about birds if you could read between the lines but rather a deft song of the self in the guise of a swashbuckling how-to. Fun with Falconry is triumphant, soaked in the sauce of boyish lyricism but fried tough in a cynic's skillet. I recommend it.

But so convincing was my book of meta-falconry that the literati could not crack its facade. "Unfortunately there is no plot," wrote one newsman, a dim observation he'll regret until some merciful downsizing at headquarters ends his ill-chosen career. Meanwhile, the book flew over the heads of the bird-of-prey trade magazines, and despite my dreams of seeing Travis LaFrance leaning against Jack London on the Literature shelf, Fun with Falconry was exiled by booksellers to the Animal Husbandry alcove, doomed to obscurity alongside Tricks for Turtles and An Introduction to Llama Packing.

So instead of spending the summer rubbing my chin on book shows and rubbing the knees of ripe coeds who would endure around-the-block waits for an autograph -- instead of that, I had returned to my honorable job in the hot Utah desert and was currently faced with the prospect of moving poo from a plastic tub to a hole in the ground. I'd taken this job with the promise that I'd be rowing boats by the end of the season, but three years later I'd proven so indispensable around the yard that the boss couldn't afford to lend me to the river.

Luckily literature had paid me in a spiritual currency more rare than job advancement. "My art is my life, and versa vice," says Falconry's stoic hero, and adopting Travis LaFrance's creed as my own, I had discovered the virtuosity of poo disposal. Since the book's publication I had even begun volunteering to do it, a development that had not only fortified my character but delighted my co-workers, who were too simple to understand me.

There is a relatively sanitary method to the task. By fastening a tube you can drain the box into the sewage hold without ever seeing its contents. But I had forsworn this tube as a cowardly apparatus. I wanted to be more like Travis LaFrance, who instead of wincing at destiny grabs it bare-handed and molds it into something beautiful.

My method was pure, expressive, a triumph of both form and function. I set the box on the concrete pad, kicked it once to its side, kicked it twice upside down, then lifted. The box had been topped off with water earlier in the day to loosen the clumps, and now with a great sucking sound there erupted a terrific mountain of shit and toilet paper and tampons and maggots, spilling green rivulets of septic chemical down its ravines. Some of my co-workers, like rubes in a fine art gallery, simply can't fathom the beauty: They gasp, they gag, they cover their eyes. But I looked on calmly. With my discriminating eye I saw a robust palette of raw tempera awaiting the infusion of human spirit.

"Jimbo," I called, as he happened to walk by. "Have you seen The Scepter?"

"You mean that nasty broom handle?"

"I mean The Scepter."

"In the Dumpster, where it belongs."

It was 100 degrees and I was sweating in my rubber boots and plastic apron and elbow-length dishwasher gloves. Though sometimes the poo is sufficiently soft to be gulped up by the hole in a single prolonged swallow, today as usual we had a clog. I had left The Scepter here in my studio for these occasions, but some unenlightened simp had apparently tossed it. Sifting through the garbage I retrieved the slender oaken staff, gripped it tightly so that our spirits might mingle, and then like Jackson Pollack stirring his bucket I plunged it forcefully through the shit heap. It was just the thing. The heap coughed, I aimed the hose, and then with a spit and a sublime gurgle the poo was slurped into the earth.

A good morning's work. I rinsed the boxes, slapping to dislodge the lonely corn kernel, then bleached the units and set them to dry. I peeled off my protective layers and washed. Saying good-bye to the guides still busy with such pedestrian tasks as washing pots and scrubbing coolers, I pitied for a moment their artless lives, then drove home to my trailer. Catching a whiff of sewage, I sniffed myself and checked my shoe soles, but didn't find any residue.

Before I reached the shower I discovered the message from New York concerning a book. Don't think I'm some hack who lets the latest glossy gazette charter me a camel ride or spelunking tour. I am an artist. Whereas young men in other generations have measured their courage by enemy gunfire, my imagined crucible concerned that inevitable million-dollar offer: Would I stand true to my craft and refuse it or would I sign on the line and go to hell with the rest of the sellouts? So before making the phone call I scrubbed to the elbows for the third time and resolved to accept no work that would demean me.

The agent and I had never met. He was a voice on the line who reported now and then that, like the work of any misunderstood visionary, my writing had not sold. My records showed that he'd earned $64.57 from our arrangement the previous year, and I imagined him at lunch in a fancy bar and grill boasting to all the other agents about the satisfaction of representing a true master. "I used to value money like you do," he'd scold them, "but that was before I found a higher calling." The other agents would sulk back to their plush offices feeling at once the hollowness of their riches and a new inspiration to exalt literature to the people.

And now things were turning around, said the agent when his assistant finally took me off hold and patched me through. A publisher wanted to pay me to write a book.

"A book about what?"

"Bullfighting."

I had never been to a bullfight.

"Are we talking six figures?" I said.

"Not quite."

"High fives?"

"Nope."

"Medium fives?"

"Upper fours," said the agent.

I did not figure that minus the agent's cut my total payment for Toro would be about seven thousand dollars. My mind computes moods, not numbers. I did not consider how much it would cost to get to the part of the world that has bullfights and live there long enough to write a book, and I certainly did not calculate how quickly I could earn that same sum in the boatyard. In a flicker of fantasy I saw the name Travis LaFrance emblazoned on another book jacket, topping the critics' top-ten lists, headlining the program for the White House reception. The more I considered a winter in Moab collecting unemployment and applying for heat assistance, the more I realized that, yes, what literature really needs at this moment is a book about bullfighting by a young white American man, and that accepting such a small advance would not be the soulless money grab of a sellout, but on the contrary would constitute proof that my work transcended monetary value. Without a hesitation I said:

"I'll do it."

The result, once I iron out a few wrinkles with the publisher, will be Toro: Encounters with Men and Bulls: An Aficionado's Odyssey from Tijuana to Mexico City and Back. Its phenomenal success will astound everyone but me. By the time you read this, Toro will have already had a long surf atop the bestseller charts, Travis LaFrance will be a talk-show staple, and critics will have talked themselves hoarse pronouncing him the next Ernest Hemingway.

Since you're reading The Making of Toro, you've surely read Toro and want to learn about the man behind Travis. If not, you'll pop down to your bookseller, where stacks of LaFrance are disappearing by the crateload, but for now a bit of background will help. Here's the proposal I wrote after the phone call from the agent, which with a few minor edits will grace the bestselling dust jacket.

Ernest Hemingway. Pablo Picasso.

Great artists and great men, united by a passion for fine women, high adventure, and la fiesta brava. In Toro: Encounters with Men and Bulls: An Aficionado's Odyssey from Tijuana to Madrid, falconer Travis LaFrance takes us on a voyage through the 21st-century remnants of the Spanish empire, in search of the flickering flame of manhood imported from Iberia five centuries ago.

His quest begins in Tijuana, the northernmost outpost of the Kingdom of Carlos, where the blood of the bulls mingles with the sweat of the laborer on his journey toward el norte. Making his way by train, burro, and thumb through the dusty villages, lured by cold cerveza and strong tequila and lusty señoritas, the ever-hardy LaFrance blends the drama and artistry of the bullring with his rich tales of love and loss, and reveals that, yes, beyond that familiar realm of the starched-shirt pencil-pushers, in a land more primitive and passionate than his own, there does yet exist a small yet robust sample of that endangered species known as man.

Toro pierces the heart of la fiesta brava, the soul of Mexico and Spain, and not least of all the spirit of Travis LaFrance.

A month has passed since I shipped the finished manuscript of Toro, and the publisher's silence has been like that of a stunned bullring after a flawless kill. But I won't postpone my victory lap waiting for those New York judges to wave a green handkerchief. No matter how great the book is, no one will read it if they don't hear about it, and I vowed early that Toro would not slip into the same cracks that held Fun with Falconry. Having seen television shows like "The Making of Titanic," I know that a blockbuster is not the work of some recluse behind a typewriter, but the result of slick marketing that hypes the final product as so fabulous that it merits a documentary on its very creation. What works for movies should work for books, and so as I set out to write Toro I also began this behind-the-scenes memoir of the forging of a classic. Call it a companion piece to genius.

So join me, reader, and learn how an average soul like myself has invented a legend. Do not be dismayed to learn that, like you, I am imperfect and fallible. Do not be disappointed that I am not the man whom you have come to admire and envy. Rather, as we study the evolution of our hero, take heart that even I, his creator, strive each day to be a bit more like Travis LaFrance.

Copyright © 2003 by Mark Sundeen

Recenzii

Outside Combining the self-deprecating wit of David Sedaris and the literary gamesmanship of Dave Eggers...Fabulously entertaining...The Making of Toro is a glorious mess, the tale of a hapless quest.

Detroit Free Press The Making of Toro...is part travelogue, part romance, part send-up of literary fashions, and wholly the mark of the quirkiest memoirist since David Sedaris.

National Geographic Adventure With Toro, Sundeen has created a consistent portrait of the artist as a young wannabe. The result is as fun, irreverent, and original as travel writing gets.

Hunter S. Thompson Books like this are written only once or twice in a century. Thank God.

Detroit Free Press The Making of Toro...is part travelogue, part romance, part send-up of literary fashions, and wholly the mark of the quirkiest memoirist since David Sedaris.

National Geographic Adventure With Toro, Sundeen has created a consistent portrait of the artist as a young wannabe. The result is as fun, irreverent, and original as travel writing gets.

Hunter S. Thompson Books like this are written only once or twice in a century. Thank God.