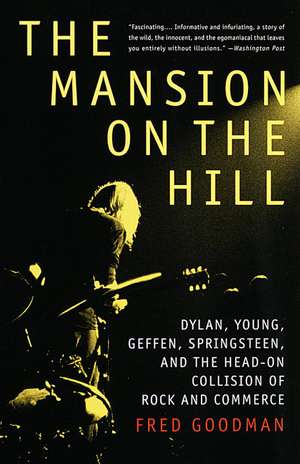

The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-On Collision of Rock and Commerce

Autor Fred Goodmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 1998

From the moment Pete Seeger tried to cut the power at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival debut of Bob Dylan's electric band, rock's cultural influence and business potential have been grasped by a rare assortment of ambitious and farsighted musicians and businessmen. Jon Landau took calls from legendary producer Jerry Wexler in his Brandeis dorm room and went on to orchestrate Bruce Springsteen's career. Albert Grossman's cold-eyed assessment of the financial power at his clients' fingertips made him the first rock manager to blaze the trail that David Geffen transformed into a superhighway. Dylan's uncanny ability to keep his manipulation of the business separate from his art and reputation prefigured the savvy -- and increasingly cynical -- professionalism of groups like the Eagles.

Fred Goodman, a longtime rock critic and journalist, digs into the contradictions and ambiguities of a generation that spurned and sought success with equal fervor. The Mansion on the Hill, named after a song title used by Hank Williams, Neil Young, and Bruce Springsteen, breaks new ground in our understanding of the people and forces that have shaped the music.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 106.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 160

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.37€ • 21.10$ • 16.100£

20.37€ • 21.10$ • 16.100£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679743774

ISBN-10: 0679743774

Pagini: 464

Ilustrații: 8-PP. B&W PHOTO SECTION

Dimensiuni: 131 x 204 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.46 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0679743774

Pagini: 464

Ilustrații: 8-PP. B&W PHOTO SECTION

Dimensiuni: 131 x 204 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.46 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Fred Goodman is a writer specializing in the music and entertainment business. From 1987 to 1990 he was a senior editor at Rolling Stone, where he is now a contributing editor. He has written for The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ, M, and The Village Voice. He lives in White Plains, New York.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Tonight, down here in the valley,

I'm lonesome and oh, how I feel,

As I sit here alone in my cabin,

I can see a mansion on the hill.

Hank Williams,

"A Mansion on the Hill"

I spent my high school summers working in the kitchen of a camp in the Poconos. It was dirty work but a great paying gig at sixty dollars a week. Of course, there wasn't a hell of a lot to do at night and that was a problem: What's the good of being sixteen and on your own if you can't go completely insane?

Sometimes we'd borrow a car and drive to New York, where the drinking age was still eighteen and we stood a better chance of getting served. But usually we'd just sit around the dilapidated shack we lived in behind the kitchen, getting loaded on whatever we could lay our hands on and listening to records. Among eight guys there were four stereos and over two thousand albums in that bunk: the bare necessities required for two months away from civilization. Music -- rock and roll -- was far and away the most discussed topic. (Girls and drugs were tied for second.)

As great as the music was, the ongoing conversation was really about something more than solos and songs. Listening to rock and roll was learning a secret language. There was something conveyed by the attitude of the bands and their records that stood apart from the music, and the way you spoke that language told people how you felt about the world. When you first met someone, the conversation turned immediately to music because once you knew which bands a person listened to, you knew if you were going to get along.

It was a lot like administering a psychological test. First you'd check to see if the basic language was there -- the Beatles, the Stones, and the British Invasion bands; Motown and Stax; the San Francisco groups; Dylan. After that, you'd probe special interests for signs of sophistication or character flaws. For instance, a passion for a perfectly acceptable but lightweight group like Steppenwolf showed a certain genial rebelliousness but suggested a lack of depth; a girl who listened to a lot of Joni Mitchell could probably be talked into bed but you might regret it later; a single-minded focus on the Grateful Dead and the New Riders of the Purple Sage was a sure sign of a heavy dope smoker; anyone with a record collection that traced the blues further back than John Mayall and the Yardbirds was an intellectual. It was, I recall, a remarkably accurate system.

Nearly twenty-five years later, after spending much of that time as a music business reporter, I'm not sure that secret language still exists. The question -- at least to someone my age -- is no longer "Will rock and roll change the world?" but "How did the world change rock and roll?"

Rock went through a dramatic transformation in the mid-sixties. The folk-rock movement brought a new artistic, social, and political intention to the music that early rockers did not have. Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis -- all were extraordinary and inventive performers, but they aspired to show business careers, not to creating lasting art. The same is true of the early Beatles, and it was folk artists -- and Bob Dylan in particular -- who changed the music's parameters and aspirations to include a quest for legitimacy, values, and authenticity -- specifically an interest in populist folk forms and populist politics of the left. Folk was entertainment, but there was a real and right way to play it. "It was musicology," Peter Wolf of the J. Geils Band remarked to me in recalling the spirit that infused the coffeehouse scene. That distinction set folk apart from what many of its fans viewed dimly as the junk culture entertainment that post-World War II consumer society produced solely for the sake of being sold. Considering the increasing rejection of those values in the early sixties, it's not surprising that folk found a new resonance, especially on college campuses, that led to the "folk boom" of that period. When Dylan and others created folk-rock, those aspirations were transferred to electric music, and the results proved far more popular and profound for the mass culture than folk had ever been. The most influential rock albums of the later part of the sixties were made by people who took themselves quite seriously -- as did their listeners.

Just a few decades ago rock was tied to a counterculture professing to be so firmly against commercial and social conventions that the notion of a "rock and roll business" seemed an oxymoron. In 1962, the year before the Beatles' debut, the $500 million record business shunned rock music -- "It smells but it sells" was the guilty refrain of those who stooped to recording and releasing rock records. With the rise of the popular rock culture in the sixties, as rock albums supplanted films and books as the most influential popular art form for young people, the mainstream entertainment industry embraced the music. At the better-run companies, the fiscal results were astounding: although largely unnoticed, the twenty-two-year history of Steve Ross's Warner Communications, Inc., reveals that the record operation was the firm's biggest, most dependable financial engine; the corporation widely considered the preeminent American media conglomerate of the age was literally fueled by rock and roll.

The entertainment industry has done more than survive its head-on collision with rock's antithetical culture -- it has thrived. This year, largely on the strength of rock, the worldwide record industry will gross over $20 billion, and global media and technology giants like Time Warner, Sony, Bertelsmann, Philips Electronics, and Thorn-EMI will view rock bands as key assets. How did this happen? And what does it mean that bands accept it?

Seriousness and artistic intent were a key part of the growing appeal of the subsequent "underground" rock scene. But the success of that scene also revolutionized the music business. It's easy to forget that in the early sixties the sound track to West Side Story was the number one album in Billboard for fifty-four weeks -- and that for certain rock stars today its sales figure would be considered disappointing. That commercial revolution had a huge and not necessarily positive effect on rock music. It bred financial opportunities for artists and a certain professionalism that has proven to be at odds with a quest for authenticity. I have nothing against commercial success, it's just not an artistic goal in and of itself. What I find most troubling is that the scope and reach of the business often make it impossible to tell what is done for art and what is done for commerce -- which calls into question the music's current ability to convey the artistic intent that made it so appealing and different to begin with. And, if the acquisition of wealth and influence is rock's ultimate meaning, then the most meaningful figure it has produced is the billionaire mogul David Geffen. Indeed, it's more than ironic that Geffen's appreciation of the dollars-and-cents value of the music has placed him in a position to exert a greater influence and power over society and politics than the artists -- it may be the measure of a profound failure by the musicians and their fans. Geffen is a visionary businessman and a generous philanthropist, but I never sat around the shack behind the kitchen when I was sixteen trying to divine the secret language of business, and I don't know anyone else who did. I wasn't looking for the mansion on the hill, and I didn't think rock and roll was, either.

From the Hardcover edition.

I'm lonesome and oh, how I feel,

As I sit here alone in my cabin,

I can see a mansion on the hill.

Hank Williams,

"A Mansion on the Hill"

I spent my high school summers working in the kitchen of a camp in the Poconos. It was dirty work but a great paying gig at sixty dollars a week. Of course, there wasn't a hell of a lot to do at night and that was a problem: What's the good of being sixteen and on your own if you can't go completely insane?

Sometimes we'd borrow a car and drive to New York, where the drinking age was still eighteen and we stood a better chance of getting served. But usually we'd just sit around the dilapidated shack we lived in behind the kitchen, getting loaded on whatever we could lay our hands on and listening to records. Among eight guys there were four stereos and over two thousand albums in that bunk: the bare necessities required for two months away from civilization. Music -- rock and roll -- was far and away the most discussed topic. (Girls and drugs were tied for second.)

As great as the music was, the ongoing conversation was really about something more than solos and songs. Listening to rock and roll was learning a secret language. There was something conveyed by the attitude of the bands and their records that stood apart from the music, and the way you spoke that language told people how you felt about the world. When you first met someone, the conversation turned immediately to music because once you knew which bands a person listened to, you knew if you were going to get along.

It was a lot like administering a psychological test. First you'd check to see if the basic language was there -- the Beatles, the Stones, and the British Invasion bands; Motown and Stax; the San Francisco groups; Dylan. After that, you'd probe special interests for signs of sophistication or character flaws. For instance, a passion for a perfectly acceptable but lightweight group like Steppenwolf showed a certain genial rebelliousness but suggested a lack of depth; a girl who listened to a lot of Joni Mitchell could probably be talked into bed but you might regret it later; a single-minded focus on the Grateful Dead and the New Riders of the Purple Sage was a sure sign of a heavy dope smoker; anyone with a record collection that traced the blues further back than John Mayall and the Yardbirds was an intellectual. It was, I recall, a remarkably accurate system.

Nearly twenty-five years later, after spending much of that time as a music business reporter, I'm not sure that secret language still exists. The question -- at least to someone my age -- is no longer "Will rock and roll change the world?" but "How did the world change rock and roll?"

Rock went through a dramatic transformation in the mid-sixties. The folk-rock movement brought a new artistic, social, and political intention to the music that early rockers did not have. Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis -- all were extraordinary and inventive performers, but they aspired to show business careers, not to creating lasting art. The same is true of the early Beatles, and it was folk artists -- and Bob Dylan in particular -- who changed the music's parameters and aspirations to include a quest for legitimacy, values, and authenticity -- specifically an interest in populist folk forms and populist politics of the left. Folk was entertainment, but there was a real and right way to play it. "It was musicology," Peter Wolf of the J. Geils Band remarked to me in recalling the spirit that infused the coffeehouse scene. That distinction set folk apart from what many of its fans viewed dimly as the junk culture entertainment that post-World War II consumer society produced solely for the sake of being sold. Considering the increasing rejection of those values in the early sixties, it's not surprising that folk found a new resonance, especially on college campuses, that led to the "folk boom" of that period. When Dylan and others created folk-rock, those aspirations were transferred to electric music, and the results proved far more popular and profound for the mass culture than folk had ever been. The most influential rock albums of the later part of the sixties were made by people who took themselves quite seriously -- as did their listeners.

Just a few decades ago rock was tied to a counterculture professing to be so firmly against commercial and social conventions that the notion of a "rock and roll business" seemed an oxymoron. In 1962, the year before the Beatles' debut, the $500 million record business shunned rock music -- "It smells but it sells" was the guilty refrain of those who stooped to recording and releasing rock records. With the rise of the popular rock culture in the sixties, as rock albums supplanted films and books as the most influential popular art form for young people, the mainstream entertainment industry embraced the music. At the better-run companies, the fiscal results were astounding: although largely unnoticed, the twenty-two-year history of Steve Ross's Warner Communications, Inc., reveals that the record operation was the firm's biggest, most dependable financial engine; the corporation widely considered the preeminent American media conglomerate of the age was literally fueled by rock and roll.

The entertainment industry has done more than survive its head-on collision with rock's antithetical culture -- it has thrived. This year, largely on the strength of rock, the worldwide record industry will gross over $20 billion, and global media and technology giants like Time Warner, Sony, Bertelsmann, Philips Electronics, and Thorn-EMI will view rock bands as key assets. How did this happen? And what does it mean that bands accept it?

Seriousness and artistic intent were a key part of the growing appeal of the subsequent "underground" rock scene. But the success of that scene also revolutionized the music business. It's easy to forget that in the early sixties the sound track to West Side Story was the number one album in Billboard for fifty-four weeks -- and that for certain rock stars today its sales figure would be considered disappointing. That commercial revolution had a huge and not necessarily positive effect on rock music. It bred financial opportunities for artists and a certain professionalism that has proven to be at odds with a quest for authenticity. I have nothing against commercial success, it's just not an artistic goal in and of itself. What I find most troubling is that the scope and reach of the business often make it impossible to tell what is done for art and what is done for commerce -- which calls into question the music's current ability to convey the artistic intent that made it so appealing and different to begin with. And, if the acquisition of wealth and influence is rock's ultimate meaning, then the most meaningful figure it has produced is the billionaire mogul David Geffen. Indeed, it's more than ironic that Geffen's appreciation of the dollars-and-cents value of the music has placed him in a position to exert a greater influence and power over society and politics than the artists -- it may be the measure of a profound failure by the musicians and their fans. Geffen is a visionary businessman and a generous philanthropist, but I never sat around the shack behind the kitchen when I was sixteen trying to divine the secret language of business, and I don't know anyone else who did. I wasn't looking for the mansion on the hill, and I didn't think rock and roll was, either.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Drawing on unprecedented candid interviews with rock's luminaries and behind-the-scenes fixers, veteran music journalist Fred Goodman takes readers from the coffee houses of 1960s Boston to the boardrooms of 1990s L.A. as he relates the uneasy alliances between visionaries like Dylan, Young, and Springsteen and the men who launched their careers. of photos.