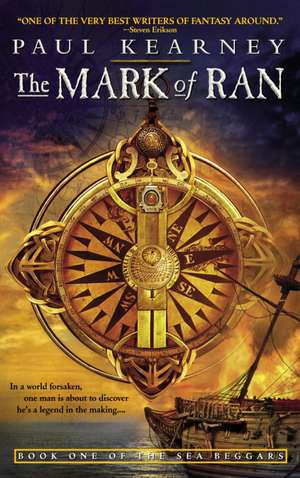

The Mark of Ran: Book One of the Sea Beggars: Sea Beggars, cartea 01

Autor Paul Kearneyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2005

In a world abandoned by its Creator, an ancient race once existed–one with powers mankind cannot imagine. Some believe they were the last of the angels. Others think they were demons. Rol Cortishane was raised in a remote fishing village with no idea of his true place in the world. But in his veins runs the blood of this long-forgotten race and he shares their dangerous destiny. Driven from home, accused of witchcraft and black magic, Rol takes refuge in the brooding tower sanctuary of the enigmatic Michal Psellos. There Rol is trained in the assassin’s craft and tutored by the beautiful but troubled Rowen. It’s no accident that Rol and Rowen have been brought together, but the truth about their past is a secret they will have to fight to discover. Now they’ve set their sights across the sea in search of the Hidden City and an adventure that will make them legends…if it doesn’t kill them first.

Preț: 107.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 161

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.56€ • 21.44$ • 17.09£

20.56€ • 21.44$ • 17.09£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 20 martie-03 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553383614

ISBN-10: 0553383612

Pagini: 303

Ilustrații: INCLUDES MAPS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 208 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Seria Sea Beggars

ISBN-10: 0553383612

Pagini: 303

Ilustrații: INCLUDES MAPS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 208 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Seria Sea Beggars

Notă biografică

Paul Kearney was born and grew up in Northern Ireland. He studied English at Oxford University and has lived for several years in both Denmark and the United States. He now lives by the sea in County Down with his wife and two dogs. His other books include the acclaimed Monarchies of God sequence.

Extras

One

Salt-blooded

"There was a god once, of course there was. an all-Father who created everything and each race to inhabit the earth. But He left us long ago, disgusted by the waywardness of His creation, and the wanton appetites of the creatures He had populated His world with. We are forsaken now, children abandoned by their father. And when God withdrew from the world, to punish us He took with Him all hope of life after death. So nothing but the worm awaits us all. No justice for the persecuted, no punishment for the wicked. And thus our world turns, spun on its axis by the greedy dreams of men."

"But there are other gods, surely," Rol said. "There is Ussa, and Ran her spouse. And Gibniu of the Anvil--"

"Lesser deities, bound to the earth even as we are, my boy. They are powerful, yes, and immortal, but they cannot create. They can only destroy, or warp what has already been made by the One God who abandoned us."

"And the Weren, what of them?"

Rol's grandfather paused, frowned. It was a long moment before he answered.

"Some say that the Weren are fallen angels, exiled here on earth in punishment for an ancient sin, others that they are Man before his Fall, Man as he should have been. But the Lesser Gods, in jealousy, broke them down and enfeebled them and produced the mankind we know now. In either case the peoples of the world are but shadows of angels, just as the Ur-men, the Unfinished Ones, are shattered travesties of humanity. For this much is true about Umer, the wheeling earth we inhabit: all things are in decay now that God has left us. The world spins ever more slowly on its axis and the sun cools year by year, century upon century. One day Umer will be a frozen ball of mud, its turning stilled at last, and it shall drift about an ashen sun in which all light has died."

The boy named Rol considered this. The evening light off the Wrywind Sea set his red-gold hair alight in a momentary kinship of color. His eyes were green as amethyst, pale as the shallows of a tropical lagoon. He was nine years old, and his arms were wrapped around his filthy, scabbed knees. An urchin with the face of an archangel.

"When did God leave the world?" he asked the old man.

"Eons ago. Before even the first of the Lesser Men opened his eyes, in the time of the Old World, before the New was born."

"How do you know all this, Grandfather?"

The old man indulged in another one of his silences. He thumbed down the glowing whitherb in his black pipe with one horny thumb, long burnt past sensibility. Behind him, in the west, the dying sun ignited a gaudy cauldron of fire on the brim of the horizon. In the shadow of the headland the waves reached languidly for the black rocks below, caressing the same stone that in winter they would pound with white fury.

"Our people have always known these things," the old man said at last, reluctantly. He turned rheumy eyes upon the bright young face beside him, and smiled. In that instant it was possible to see that in his youth he, too, had been beautiful.

"The Dennifreians? Why do farmers and fishermen keep all this lore to themselves? Why--"

"For the last time, Rol, you and I, and Morin and Ayd who watch over you, we are not from Dennifrey. We come from--elsewhere."

"So you say. But where, Grandfather?" The boy's face had hardened into stubbornness as all children's will at the wheedling of some secret knowledge.

His grandfather puffed thoughtfully on his pipe, and stared up at the first stars that had come chasing the sunset. He seemed to be looking for something in the empurpling sky, and when he found it he pointed with one brown, corded arm. "See that star there?"

"The one that flashes blue? That's Quintillian. Bionar's Guard they call him too. Set your course by him and you'll come in the end to Urbonetto of the Wharves, the Free City."

Grandfather smiled. "Well done. But he was once called something else. Or-Desyr he was to me, when I was as young as you are now. Don't you be telling that to no one now. That's a secret, the name of our star, for us alone to know."

The boy nodded solemnly, deflated because the secret had been so small a thing as a name that meant nothing to him. And whom could he tell?

"You said we were not from Dennifrey," he pointed out sulkily. "What's a star got to do with that?"

"The star points home," his grandfather said patiently.

"We're from Urbonetto, then?"

"No! We're far beyond that, beyond mighty Bionar and Perilar and even fabled Uruban of the Silk. Remember this: Or-Desyr, or the Guard as they call him, he points over the Oronthic Sea, at the edge of Tethis herself. In those great waters it is said he can be followed to a place where one such as us may be safe, for a little while at least. But never mind that. It's a matter for another day. Look, the night has come upon us unawares."

It was indeed dark now, and behind them Morin and Ayd had lit the lamps so that kindly yellow light flickered out of the doorway of the cottage they all shared. They heard the click of wooden plates, Ayd's sharp voice berating Morin for some domestic infraction. A yellow rectangle of firelight flooded out of the doorway, waxing steadily as the darkness deepened around them and the coastal kirwits began to rasp their nightsong.

"Tethis sleeps," the old man said, staring out at the quiet sea. "See the swell? Ussa is combing her hair."

They watched the starlight as it glittered on the successive small waves lapping the rocks.

"I will sail the sea one day," Rol whispered fiercely. "I will visit every country and kingdom in the world. I will captain the finest ship ever built."

"Perhaps you will," said Rol's grandfather softly. "It is in your blood, after all. And all things came out of the sea in the Beginning. Even the mountains once were mud in the dark of Ussa's Womb. To the sea shall it all return before the end of days. Only when the sun grows cold will Ussa herself die, and the surface of the earth know stillness at last."

He stood up, gripping the shoulder of the boy beside him and groaning. The bowl of his pipe glowed red and he spat fragrant smoke into the night air.

"Come, Rol. Ussa will wait for you and that ship of yours, but it's time for supper and Ayd is not so patient. The pigs have seen too many of my meals lately."

Dennifrey of the Nets, easternmost of the Seven Isles, and most insular of the seven. The shallow water of the Wrywind Sea lapped its dour shores, famed for fogs and the treacherous Severed Banks that never twice appeared on the same longitude. The Dennifreians were wedded in a bitch-marriage to the sea, a nation canny with small boats, near with their welcome to strangers, giving grudging obeisance to Ussa of the Swells, sometimes slaughtering a kid to her consort, vicious Ran, to placate his winter storms. It was as though they hated the element upon which their craft floated.

They rode it as warily as a man might a skittish horse. But their fishing grounds were the richest in the northern world, and the Dennifreians had done well out of their hag-ridden union. They had become prosperous, and yet their wealth had not rendered them any more receptive to the matters of the world beyond their shores. Almost they gloried in their ignorance, and viewed the Fisher-Merchants who took the salted choice of their catch abroad with disdain.

A small payment for this fish-fueled prosperity of theirs--a steady trickle of lives every year lost to Ran's Nets, the blood-price for their tenure of the sea's riches. Perhaps it was that which made them dour, for they were a folk apt to strike hard bargains, and to resent it when in their turn they had one forced upon themselves. But one does not argue with the gods. So they cursed the sea when they were not out upon her breast, and their offerings were made with ill grace.

Rol's family--for so he thought of them though Morin and Ayd were no kin to him--had lived on Dennifrey for many years. And yet still they were outsiders, and Grandfather could bring stillness to a packed tavern in Driol merely by peering across the threshold.

"We are the flotsam of an old hatred," he had told Rol, "set adrift by the fear and ignorance of men."

He said many things of that sort, so many that even Rol now barely heard them. Grandfather had a rolling, lilted voice as deep as a barrel, musical as a lark, but he did so love to listen to it, and to make sonorous pronouncements about things Rol had no hope of ever understanding. So he and Morin would sit by the cottage wall mending the nets, nodding without knowing, for they loved the old man.

They lived separate and apart, the odd quartet, their cottage built by Morin out of wherzstone blocks, and set on a jutting promontory from which the shipping of the Twelve Seas could be seen in skeins of sails on the turquoise horizon. Eyrie, Grandfather had long before named their little dwelling, insisting that a house needed a name much as did a ship. And the house was good to them, as if appreciative of the thought. Roofed with turves and constructed as squarely as a redoubt, Eyrie shrugged off winter gales and crackling summer heat alike. It was the only home Rol had ever known, or would ever really know, a solid permanence at the center of his young life.

Below the cottage was a tiny crescent-shaped cove where they beached the wherry in winter, and behind it Ayd had crafted a rood of good soil with infinite labor and tons of seaweed, so they had fresh vegetables without haggling over them in town. Beyond it, in a small plashed wood, two pigs rooted in genial ignorance of their approaching fate, their black-striped offspring squealing for their teats.

On the very crumbling tip of the promontory loomed a hagrolith, cold even on the hottest Midsummer Day, and casting no shadow at sunset. The local folk refused to go near it, and yet Rol's family had made their home within sight of its mossy flanks, and Rol thought of the stone as one might of a distant and seldom-seen relative, neither good nor ill, but part of the mental landscape. Grandfather often sat with his back to the stone, even in winter, and watched the endless progression of the sea-swells as they came traveling across the Wrywind.

The familiar landscape was circumscribed by the emptiness of the high moorland about the promontory. This was a wide waste of heather and scrub and bracken, soft going underfoot, and in wet seasons treacherous to those who did not know about the bogs and quagmires it spawned. No one lived there; it was left to the deer and the rabbits and the buzzards.

There were only intermittent contacts with the local people. Serioc the Headman of Driol would drop by once a year for the Tollcount, and though he would not enter the house, he would share a flagon of barley beer with Grandfather in something of an annual ritual, and would ask the same polite questions, then leave with the sweat cold upon his brow and the relief staring out of his eyes. But it would raise his standing in town for him to say he had dared to sup with the folk on the headland, and his re-election as Headman would be assured.

And Ayd would tramp the muddy miles into Driol once every few months to barter for those necessities that they could not make or grow or catch for themselves. Yarn for net-making, whitherb for Grandfather's pipe, a new axe blade or kitchen knife to replace one worn to the quick, and always a great sack of yellow flour for their twice-weekly loaves. On her return the strap of her back-basket would leave a red bar across her forehead for days to mark the trip, and she would be slightly less cross-grained and irritable than usual, either because she liked going into town, or because she was glad to have it over with. After each trip she would always spend the following night out on the moors--to clear her head, she said--and would invariably return in the morning muddy and scratched, but with a brace of conies dangling from one fist, or more rarely a young deer, its neck broken and dangling.

One clear autumn afternoon Rol had fared farther afield than usual, blackberrying on the western slopes of the headland, when he had come across a knot of the local boys engaged in the same quest. He was large, and broad-shouldered for his age, but even he could do little when they pounced on him en masse and commenced pummeling his head into the springy short-grassed turf. His baffled astonishment gave way to fury, and he managed to plant his fist between the eyes of their sandy-haired ringleader. This merely fed their viciousness, however, and they were casting about for a suitable stone with which to crush his skull when out of nowhere Morin appeared. Rol lifted his bloodied head from the grass to see their faces go gray with terror, and abandoning their berry baskets, they fled, pelting back toward the town with a collective wail and nary a backward glance. But when Rol had looked at his rescuer, Morin was merely smiling his vacant-minded smile, like an amiable bear. Only for a second did he think he saw something else in the big man's face, an emerald gleam in the eye, a strange blurred definition to his countenance. He put it down to the ringing in his head, and forgot it in the wealth of blackberry jam that ensued.

They avoided him after that, the village boys, and often as he tramped about the sere upland moors above the headland with his birding bow and game bag, he would see them at their play, and feel an odd pang as they took to their heels when they sighted him. He was not solitary by nature, and as he grew older he wearied of Ayd's carping, Morin's simpleminded placidity, his grandfather's absurd tales and dark mutterings. It was a great joy to him when he was pronounced old enough to go out in the wherry with Morin, and take his chances with the whims of Ran and Ussa on the Wrywind.

Salt-blooded

"There was a god once, of course there was. an all-Father who created everything and each race to inhabit the earth. But He left us long ago, disgusted by the waywardness of His creation, and the wanton appetites of the creatures He had populated His world with. We are forsaken now, children abandoned by their father. And when God withdrew from the world, to punish us He took with Him all hope of life after death. So nothing but the worm awaits us all. No justice for the persecuted, no punishment for the wicked. And thus our world turns, spun on its axis by the greedy dreams of men."

"But there are other gods, surely," Rol said. "There is Ussa, and Ran her spouse. And Gibniu of the Anvil--"

"Lesser deities, bound to the earth even as we are, my boy. They are powerful, yes, and immortal, but they cannot create. They can only destroy, or warp what has already been made by the One God who abandoned us."

"And the Weren, what of them?"

Rol's grandfather paused, frowned. It was a long moment before he answered.

"Some say that the Weren are fallen angels, exiled here on earth in punishment for an ancient sin, others that they are Man before his Fall, Man as he should have been. But the Lesser Gods, in jealousy, broke them down and enfeebled them and produced the mankind we know now. In either case the peoples of the world are but shadows of angels, just as the Ur-men, the Unfinished Ones, are shattered travesties of humanity. For this much is true about Umer, the wheeling earth we inhabit: all things are in decay now that God has left us. The world spins ever more slowly on its axis and the sun cools year by year, century upon century. One day Umer will be a frozen ball of mud, its turning stilled at last, and it shall drift about an ashen sun in which all light has died."

The boy named Rol considered this. The evening light off the Wrywind Sea set his red-gold hair alight in a momentary kinship of color. His eyes were green as amethyst, pale as the shallows of a tropical lagoon. He was nine years old, and his arms were wrapped around his filthy, scabbed knees. An urchin with the face of an archangel.

"When did God leave the world?" he asked the old man.

"Eons ago. Before even the first of the Lesser Men opened his eyes, in the time of the Old World, before the New was born."

"How do you know all this, Grandfather?"

The old man indulged in another one of his silences. He thumbed down the glowing whitherb in his black pipe with one horny thumb, long burnt past sensibility. Behind him, in the west, the dying sun ignited a gaudy cauldron of fire on the brim of the horizon. In the shadow of the headland the waves reached languidly for the black rocks below, caressing the same stone that in winter they would pound with white fury.

"Our people have always known these things," the old man said at last, reluctantly. He turned rheumy eyes upon the bright young face beside him, and smiled. In that instant it was possible to see that in his youth he, too, had been beautiful.

"The Dennifreians? Why do farmers and fishermen keep all this lore to themselves? Why--"

"For the last time, Rol, you and I, and Morin and Ayd who watch over you, we are not from Dennifrey. We come from--elsewhere."

"So you say. But where, Grandfather?" The boy's face had hardened into stubbornness as all children's will at the wheedling of some secret knowledge.

His grandfather puffed thoughtfully on his pipe, and stared up at the first stars that had come chasing the sunset. He seemed to be looking for something in the empurpling sky, and when he found it he pointed with one brown, corded arm. "See that star there?"

"The one that flashes blue? That's Quintillian. Bionar's Guard they call him too. Set your course by him and you'll come in the end to Urbonetto of the Wharves, the Free City."

Grandfather smiled. "Well done. But he was once called something else. Or-Desyr he was to me, when I was as young as you are now. Don't you be telling that to no one now. That's a secret, the name of our star, for us alone to know."

The boy nodded solemnly, deflated because the secret had been so small a thing as a name that meant nothing to him. And whom could he tell?

"You said we were not from Dennifrey," he pointed out sulkily. "What's a star got to do with that?"

"The star points home," his grandfather said patiently.

"We're from Urbonetto, then?"

"No! We're far beyond that, beyond mighty Bionar and Perilar and even fabled Uruban of the Silk. Remember this: Or-Desyr, or the Guard as they call him, he points over the Oronthic Sea, at the edge of Tethis herself. In those great waters it is said he can be followed to a place where one such as us may be safe, for a little while at least. But never mind that. It's a matter for another day. Look, the night has come upon us unawares."

It was indeed dark now, and behind them Morin and Ayd had lit the lamps so that kindly yellow light flickered out of the doorway of the cottage they all shared. They heard the click of wooden plates, Ayd's sharp voice berating Morin for some domestic infraction. A yellow rectangle of firelight flooded out of the doorway, waxing steadily as the darkness deepened around them and the coastal kirwits began to rasp their nightsong.

"Tethis sleeps," the old man said, staring out at the quiet sea. "See the swell? Ussa is combing her hair."

They watched the starlight as it glittered on the successive small waves lapping the rocks.

"I will sail the sea one day," Rol whispered fiercely. "I will visit every country and kingdom in the world. I will captain the finest ship ever built."

"Perhaps you will," said Rol's grandfather softly. "It is in your blood, after all. And all things came out of the sea in the Beginning. Even the mountains once were mud in the dark of Ussa's Womb. To the sea shall it all return before the end of days. Only when the sun grows cold will Ussa herself die, and the surface of the earth know stillness at last."

He stood up, gripping the shoulder of the boy beside him and groaning. The bowl of his pipe glowed red and he spat fragrant smoke into the night air.

"Come, Rol. Ussa will wait for you and that ship of yours, but it's time for supper and Ayd is not so patient. The pigs have seen too many of my meals lately."

Dennifrey of the Nets, easternmost of the Seven Isles, and most insular of the seven. The shallow water of the Wrywind Sea lapped its dour shores, famed for fogs and the treacherous Severed Banks that never twice appeared on the same longitude. The Dennifreians were wedded in a bitch-marriage to the sea, a nation canny with small boats, near with their welcome to strangers, giving grudging obeisance to Ussa of the Swells, sometimes slaughtering a kid to her consort, vicious Ran, to placate his winter storms. It was as though they hated the element upon which their craft floated.

They rode it as warily as a man might a skittish horse. But their fishing grounds were the richest in the northern world, and the Dennifreians had done well out of their hag-ridden union. They had become prosperous, and yet their wealth had not rendered them any more receptive to the matters of the world beyond their shores. Almost they gloried in their ignorance, and viewed the Fisher-Merchants who took the salted choice of their catch abroad with disdain.

A small payment for this fish-fueled prosperity of theirs--a steady trickle of lives every year lost to Ran's Nets, the blood-price for their tenure of the sea's riches. Perhaps it was that which made them dour, for they were a folk apt to strike hard bargains, and to resent it when in their turn they had one forced upon themselves. But one does not argue with the gods. So they cursed the sea when they were not out upon her breast, and their offerings were made with ill grace.

Rol's family--for so he thought of them though Morin and Ayd were no kin to him--had lived on Dennifrey for many years. And yet still they were outsiders, and Grandfather could bring stillness to a packed tavern in Driol merely by peering across the threshold.

"We are the flotsam of an old hatred," he had told Rol, "set adrift by the fear and ignorance of men."

He said many things of that sort, so many that even Rol now barely heard them. Grandfather had a rolling, lilted voice as deep as a barrel, musical as a lark, but he did so love to listen to it, and to make sonorous pronouncements about things Rol had no hope of ever understanding. So he and Morin would sit by the cottage wall mending the nets, nodding without knowing, for they loved the old man.

They lived separate and apart, the odd quartet, their cottage built by Morin out of wherzstone blocks, and set on a jutting promontory from which the shipping of the Twelve Seas could be seen in skeins of sails on the turquoise horizon. Eyrie, Grandfather had long before named their little dwelling, insisting that a house needed a name much as did a ship. And the house was good to them, as if appreciative of the thought. Roofed with turves and constructed as squarely as a redoubt, Eyrie shrugged off winter gales and crackling summer heat alike. It was the only home Rol had ever known, or would ever really know, a solid permanence at the center of his young life.

Below the cottage was a tiny crescent-shaped cove where they beached the wherry in winter, and behind it Ayd had crafted a rood of good soil with infinite labor and tons of seaweed, so they had fresh vegetables without haggling over them in town. Beyond it, in a small plashed wood, two pigs rooted in genial ignorance of their approaching fate, their black-striped offspring squealing for their teats.

On the very crumbling tip of the promontory loomed a hagrolith, cold even on the hottest Midsummer Day, and casting no shadow at sunset. The local folk refused to go near it, and yet Rol's family had made their home within sight of its mossy flanks, and Rol thought of the stone as one might of a distant and seldom-seen relative, neither good nor ill, but part of the mental landscape. Grandfather often sat with his back to the stone, even in winter, and watched the endless progression of the sea-swells as they came traveling across the Wrywind.

The familiar landscape was circumscribed by the emptiness of the high moorland about the promontory. This was a wide waste of heather and scrub and bracken, soft going underfoot, and in wet seasons treacherous to those who did not know about the bogs and quagmires it spawned. No one lived there; it was left to the deer and the rabbits and the buzzards.

There were only intermittent contacts with the local people. Serioc the Headman of Driol would drop by once a year for the Tollcount, and though he would not enter the house, he would share a flagon of barley beer with Grandfather in something of an annual ritual, and would ask the same polite questions, then leave with the sweat cold upon his brow and the relief staring out of his eyes. But it would raise his standing in town for him to say he had dared to sup with the folk on the headland, and his re-election as Headman would be assured.

And Ayd would tramp the muddy miles into Driol once every few months to barter for those necessities that they could not make or grow or catch for themselves. Yarn for net-making, whitherb for Grandfather's pipe, a new axe blade or kitchen knife to replace one worn to the quick, and always a great sack of yellow flour for their twice-weekly loaves. On her return the strap of her back-basket would leave a red bar across her forehead for days to mark the trip, and she would be slightly less cross-grained and irritable than usual, either because she liked going into town, or because she was glad to have it over with. After each trip she would always spend the following night out on the moors--to clear her head, she said--and would invariably return in the morning muddy and scratched, but with a brace of conies dangling from one fist, or more rarely a young deer, its neck broken and dangling.

One clear autumn afternoon Rol had fared farther afield than usual, blackberrying on the western slopes of the headland, when he had come across a knot of the local boys engaged in the same quest. He was large, and broad-shouldered for his age, but even he could do little when they pounced on him en masse and commenced pummeling his head into the springy short-grassed turf. His baffled astonishment gave way to fury, and he managed to plant his fist between the eyes of their sandy-haired ringleader. This merely fed their viciousness, however, and they were casting about for a suitable stone with which to crush his skull when out of nowhere Morin appeared. Rol lifted his bloodied head from the grass to see their faces go gray with terror, and abandoning their berry baskets, they fled, pelting back toward the town with a collective wail and nary a backward glance. But when Rol had looked at his rescuer, Morin was merely smiling his vacant-minded smile, like an amiable bear. Only for a second did he think he saw something else in the big man's face, an emerald gleam in the eye, a strange blurred definition to his countenance. He put it down to the ringing in his head, and forgot it in the wealth of blackberry jam that ensued.

They avoided him after that, the village boys, and often as he tramped about the sere upland moors above the headland with his birding bow and game bag, he would see them at their play, and feel an odd pang as they took to their heels when they sighted him. He was not solitary by nature, and as he grew older he wearied of Ayd's carping, Morin's simpleminded placidity, his grandfather's absurd tales and dark mutterings. It was a great joy to him when he was pronounced old enough to go out in the wherry with Morin, and take his chances with the whims of Ran and Ussa on the Wrywind.

Recenzii

"[A] gritty fantasy swashbuckler.... Kearney’s crisp, often lyrical writing shines brightest when his characters take to the sea."--Publishers Weekly

Descriere

Two assassins-in-training might belong to an ancient, powerful race thought by some to be exiled angels and by others to be demons. The deadly truths will launch Rol Cortishane and Rowan on a dangerous quest.