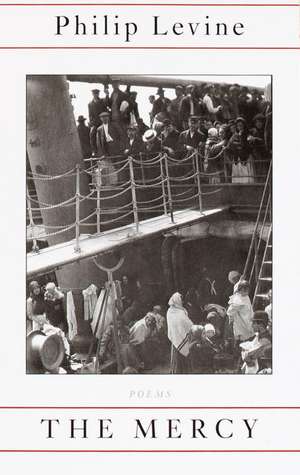

The Mercy: Poems

Autor Philip Levine, Poets Laureate Collection (Library of Coen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2000

Preț: 90.91 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.40€ • 18.21$ • 14.39£

17.40€ • 18.21$ • 14.39£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375701351

ISBN-10: 0375701354

Pagini: 96

Dimensiuni: 147 x 229 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Knopf Publishing Group

ISBN-10: 0375701354

Pagini: 96

Dimensiuni: 147 x 229 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Knopf Publishing Group

Notă biografică

Philip Levine was born in 1928 in Detroit, where he was formally educated in the public schools and at Wayne University (now Wayne State University). After a succession of industrial jobs, he left the country before settling in Fresno, California, where he taught at the university there until his retirement. He has received many awards for his books of poems, most recently the National Book Award in 1991 for What Work Is, and the Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for The Simple Truth.

Extras

The Unknowable

Practicing his horn on the Williamsburg Bridge

hour after hour, "woodshedding" the musicians

called it, but his woodshed was the world.

The enormous tone he borrowed from Hawkins

that could fill a club to overflowing

blown into tatters by the sea winds

teaching him humility, which he carries

with him at all times, not as an amulet

against the powers of animals and men

that mean harm or the lure of the marketplace.

No, a quality of the gaze downward

on the streets of Brooklyn or Manhattan.

Hold his hand and you'll see it, hold his eyes

in yours and you'll hear the wind singing

through the cables of the bridge that was home,

singing through his breath--no rarer than yours,

though his became the music of the world

thirty years ago. Today I ask myself

how he knew the time had come to inhabit

the voice of the air and how later

he decided the time had come for silence,

for the world to speak any way it could?

He wouldn't answer because he'd find

the question pompous. He plays for money.

The years pass, and like the rest of us

he ages, his hair and beard whiten, the great

shoulders narrow. He is merely a man--

after all--a man who stared for years

into the breathy, unknowable voice

of silence and captured the music.

The Return

All afternoon my father drove the country roads

between Detroit and Lansing. What he was looking for

I never learned, no doubt because he never knew himself,

though he would grab any unfamiliar side road

and follow where it led past fields of tall sweet corn

in August or in winter those of frozen sheaves.

Often he'd leave the Terraplane beside the highway

to enter the stunned silence of mid-September,

his eyes cast down for a sign, the only music

his own breath or the wind tracking slowly through

the stalks or riding above the barren ground. Later

he'd come home, his dress shoes coated with dust or mud,

his long black overcoat stained or tattered

at the hem, sit wordless in his favorite chair,

his necktie loosened, and stare at nothing. At first

my brothers and I tried conversation, questions

only he could answer: Why had he gone to war?

Where did he learn Arabic? Where was his father?

I remember none of this. I read it all later,

years later as an old man, a grandfather myself,

in a journal he left my mother with little drawings

of ruined barns and telephone poles, receding

toward a future he never lived, aphorisms

from Montaigne, Juvenal, Voltaire, and perhaps a few

of his own: "He who looks for answers finds questions."

Three times he wrote, "I was meant to be someone else,"

and went on to describe the perfumes of the damp fields.

"It all starts with seeds," and a pencil drawing

of young apple trees he saw somewhere or else dreamed.

I inherited the book when I was almost seventy

and with it the need to return to who we were.

In the Detroit airport I rented a Taurus;

the woman at the counter was bored or crazy:

Did I want company? she asked; she knew every road

from here to Chicago. She had a slight accent,

Dutch or German, long black hair, and one frozen eye.

I considered but decided to go alone,

determined to find what he had never found.

Slowly the autumn morning warmed, flocks of starlings

rose above the vacant fields and blotted out the sun.

I drove on until I found the grove of apple trees

heavy with fruit, and left the car, the motor running,

beside a sagging fence, and entered his life

on my own for maybe the first time. A crow welcomed

me home, the sun rode above, austere and silent,

the early afternoon was cloudless, perfect.

When the crow dragged itself off to another world,

the shade deepened slowly in pools that darkened around

the trees; for a moment everything in sight stopped.

The wind hummed in my good ear, not words exactly,

not nonsense either, nor what I spoke to myself,

just the language creation once wakened to.

I took off my hat, a mistake in the presence

of my father's God, wiped my brow with what I had,

the back of my hand, and marveled at what was here:

nothing at all except the stubbornness of things.

Practicing his horn on the Williamsburg Bridge

hour after hour, "woodshedding" the musicians

called it, but his woodshed was the world.

The enormous tone he borrowed from Hawkins

that could fill a club to overflowing

blown into tatters by the sea winds

teaching him humility, which he carries

with him at all times, not as an amulet

against the powers of animals and men

that mean harm or the lure of the marketplace.

No, a quality of the gaze downward

on the streets of Brooklyn or Manhattan.

Hold his hand and you'll see it, hold his eyes

in yours and you'll hear the wind singing

through the cables of the bridge that was home,

singing through his breath--no rarer than yours,

though his became the music of the world

thirty years ago. Today I ask myself

how he knew the time had come to inhabit

the voice of the air and how later

he decided the time had come for silence,

for the world to speak any way it could?

He wouldn't answer because he'd find

the question pompous. He plays for money.

The years pass, and like the rest of us

he ages, his hair and beard whiten, the great

shoulders narrow. He is merely a man--

after all--a man who stared for years

into the breathy, unknowable voice

of silence and captured the music.

The Return

All afternoon my father drove the country roads

between Detroit and Lansing. What he was looking for

I never learned, no doubt because he never knew himself,

though he would grab any unfamiliar side road

and follow where it led past fields of tall sweet corn

in August or in winter those of frozen sheaves.

Often he'd leave the Terraplane beside the highway

to enter the stunned silence of mid-September,

his eyes cast down for a sign, the only music

his own breath or the wind tracking slowly through

the stalks or riding above the barren ground. Later

he'd come home, his dress shoes coated with dust or mud,

his long black overcoat stained or tattered

at the hem, sit wordless in his favorite chair,

his necktie loosened, and stare at nothing. At first

my brothers and I tried conversation, questions

only he could answer: Why had he gone to war?

Where did he learn Arabic? Where was his father?

I remember none of this. I read it all later,

years later as an old man, a grandfather myself,

in a journal he left my mother with little drawings

of ruined barns and telephone poles, receding

toward a future he never lived, aphorisms

from Montaigne, Juvenal, Voltaire, and perhaps a few

of his own: "He who looks for answers finds questions."

Three times he wrote, "I was meant to be someone else,"

and went on to describe the perfumes of the damp fields.

"It all starts with seeds," and a pencil drawing

of young apple trees he saw somewhere or else dreamed.

I inherited the book when I was almost seventy

and with it the need to return to who we were.

In the Detroit airport I rented a Taurus;

the woman at the counter was bored or crazy:

Did I want company? she asked; she knew every road

from here to Chicago. She had a slight accent,

Dutch or German, long black hair, and one frozen eye.

I considered but decided to go alone,

determined to find what he had never found.

Slowly the autumn morning warmed, flocks of starlings

rose above the vacant fields and blotted out the sun.

I drove on until I found the grove of apple trees

heavy with fruit, and left the car, the motor running,

beside a sagging fence, and entered his life

on my own for maybe the first time. A crow welcomed

me home, the sun rode above, austere and silent,

the early afternoon was cloudless, perfect.

When the crow dragged itself off to another world,

the shade deepened slowly in pools that darkened around

the trees; for a moment everything in sight stopped.

The wind hummed in my good ear, not words exactly,

not nonsense either, nor what I spoke to myself,

just the language creation once wakened to.

I took off my hat, a mistake in the presence

of my father's God, wiped my brow with what I had,

the back of my hand, and marveled at what was here:

nothing at all except the stubbornness of things.

Recenzii

"Narrative poems of remarkable honesty and beauty--lines that speak softly and need not raise their voice to capture our full attention."

-- Sarah Manguso, Boston Book Review

"The Mercy is a book for the twenty-first century, revealing the diversity out of which Americans emerged and toward which we continue . . . In our rapidly changing world, we need such vision."

--Kate Daniels, Southern Review

-- Sarah Manguso, Boston Book Review

"The Mercy is a book for the twenty-first century, revealing the diversity out of which Americans emerged and toward which we continue . . . In our rapidly changing world, we need such vision."

--Kate Daniels, Southern Review