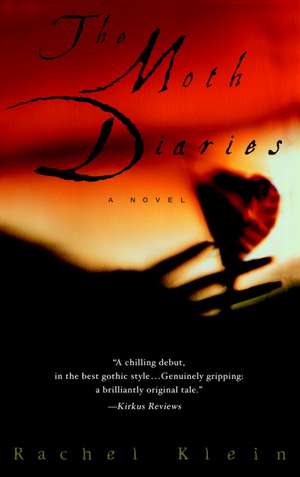

The Moth Diaries

Autor Rachel Kleinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2003

What I saw wasn’t real. And I know it wasn’t a dream.

Ernessa is a vampire.

At an exclusive girls’ boarding school, a sixteen-year-old girl records her most intimate thoughts in a diary. The object of her growing obsession is her roommate, Lucy Blake, and Lucy’s friendship with their new and disturbing classmate. Ernessa is an enigmatic, moody presence with pale skin and hypnotic eyes.

Around her swirl dark rumors, suspicions, and secrets as well as a series of ominous disasters. As fear spreads through the school and Lucy isn’t Lucy anymore, fantasy and reality mingle until what is true and what is dreamed bleed together into a waking nightmare that evokes with gothic menace the anxieties, lusts, and fears of adolescence. And at the center of the diary is the question that haunts all who read it: Is Ernessa really a vampire? Or has the narrator trapped herself in the fevered world of her own imagining?

Preț: 105.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.09€ • 20.90$ • 16.59£

20.09€ • 20.90$ • 16.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553382181

ISBN-10: 0553382187

Pagini: 246

Dimensiuni: 132 x 210 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0553382187

Pagini: 246

Dimensiuni: 132 x 210 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Bantam Books

Extras

Preface

When Dr. Karl Wolff first suggested publishing the journal that I kept during my junior year in boarding school, I thought I hadn’t heard him correctly. He’s been interested in me—or maybe I should say my case—since I was under his psychiatric care, and we talk on the phone every year or so. But I hadn’t seen the journal since I handed it over to him in the hospital thirty years ago, and we discussed it on only one occasion, when he made it clear I needed to put that period of my life behind me. Giving up writing in the journal was a first step.

My instinctive response to publication was to say no. I didn’t write the journal with the intention of having anyone else read it. And Dr. Wolff kept it only because of a promise he made to my mother before I left the hospital. I wrote it to preserve my sixteen-year-old self. Or at least that’s what I thought at the time. Besides, I have a daughter who is the same age I was when I kept this journal, and I want to protect her. I don’t feel that she needs to know everything about me.

Dr. Wolff reassured me. All the names would be changed. It would be impossible to recognize me in the person of the narrator. It would even be difficult to recognize the school. Above all, he felt the journal would be an invaluable addition to the literature on female adolescence at a time when risk-taking behavior has reached epidemic proportions. He happened to reread it while packing up his office before retirement and was struck by how convincing my writing was.

I’m not sure I agree with him. But I have always been intrigued by the journals that girls keep. They are like dollhouses. Once you look inside them, the rest of the world seems very far away, even unbelievable. If only we had the power to leap outside ourselves at such moments, we would spare ourselves so much pain and fear. I’m not talking about truth or falsehood but about surviving.

I agreed to Dr. Wolff’s suggestion with reservations. If, after reading my journal, I felt he was right, I would allow him to arrange for its publication. Dr. Wolff also asked me to write an afterword, as a kind of closure on the experience. He felt it was relatively rare for someone suffering from borderline personality disorder complicated by depression and psychosis to recover and never have another “episode,” as he so kindly put it. He was sure my reactions to the journal would be illuminating.

I can’t begin to judge that. When I opened this notebook, I found the razor blade I had hidden among the pages so long ago. Dr. Wolff had kept it as part of the “clinical picture,” as he explained. It looked utterly incongruous. It was just a razor blade. And the words on the page were just that—words in a familiar handwriting.

To anyone who wonders whether it’s possible to survive adolescence, that’s as much as I can offer of reassurance.

September

September 10

My mother dropped me off at two. Practically everyone is back. Except for Lucy. I can’t wait for her to come so that we can unpack together. I’m going to write in my journal until she’s here.

After my mother left, I felt an emptiness in my stomach that spread up through my throat to the back of my eyes. I didn’t cry, even though I probably would have felt better afterward. I needed to hold on to that feeling, that pain. If Lucy had been here, she would have distracted me. I had a moment of panic when I said good-bye to my mother. I almost begged her not to leave me here. It’s so strange. I’ve been looking forward to school for the past month. I was even excited when I got my new uniforms in the mail. The light blue spring skirt was as stiff as cardboard. I had to wash it before I could wear it. I’m glad I’m not a day student, worried about how I look on the train ride home. They sneak into the bathroom at the station and put on makeup and change from their saddle shoes into loafers, in case they run into boys they know on the train. I’ve seen them waiting for the train with their skirts hiked above their knees, and it’s hard to tell that they are wearing a uniform. We boarders couldn’t care less if we look like nurses.

Now that I’m here, I want to run away.

I’m always afraid to leave my mother. I’m afraid that I’ll never see her again. I want to run after her like a little girl, grab onto her skirt, grope for her hand, sniffle. Instead I stand very stiff and don’t say a word. “Can’t you at least say good-bye?” she says. After a few days, I get caught up in school. Then I’m glad to be away from her, even though she’s all I have left. I like to get letters from her, but I hate it when she calls. I never call her. Her voice is so heavy. It pulls me down. I’m always scared when I’m called to the phone. It’s incredibly hard for me to put the receiver to my ear. It wants to swallow me. I’m struggling to lift it, while the person on the other end is hanging in space, waiting for my voice.

From my window, I watched my mother speed down the drive. I lost sight of her car behind the Workshop. When she turned left onto the avenue, I could see it again, a streak of blue flashing through the black fence. And then she was gone. My mother always drives too fast; she doesn’t care what happens to her. Lucy’s mother would never drive like that.

I stood at the window for a long time. Then I turned around and looked at my room, my new room, with my trunk and bags and boxes piled up in the middle of the floor. It isn’t as wonderful as I had thought it would be all summer long. The walls are dirty. The girl who lived here last year left smudged black fingerprints in odd places. There’s nothing on the floor. Under the window is a chair with wooden arms, covered in tan and pink flowered material. It’s not very inviting. I think I’ll put some pillows on the sill and turn it into a window seat. I thought it would be the best room in the Residence. When I’ve unpacked and Lucy is next door, it will be different.

I got tired of waiting for Lucy, so I took a walk up to the train station. In the stationery store next to the drugstore, I found an old French composition book with a mottled crimson cover and a thick black spine, like a real book, but with blank pages. Somehow it ended up in the back of the store, forgotten. I grabbed it and walked up to the register, hugging it to my chest, afraid someone might snatch it away from me. It’s exactly like the journals my father used to keep. It was a sign, and I had to buy it. Now I’m going to fill it with words, the way he filled his notebooks: the pages, the margins, the endpapers all covered with little notes that made no sense to anyone else. I won’t tell anyone about it, not even Lucy.

I read the Claudine books over the summer. They were a replacement for school, which I missed so much. I hope the words flow from my pen onto the paper the way they did for Colette: the exact words I need. I’ve got Claudine at School on my desk, for inspiration. She knows what it’s like to be shut up in a place like this, where all your emotions are focused on the girls around you, where you dream of a boyfriend but only feel comfortable with your arm around another girl’s waist.

Already I’ve put too many sad thoughts down on these pages. I have to start all over again, very slowly and carefully. Everything has to be perfect. I’m not in a hurry. First, I open the notebook on my desk, flatten the smooth pages ruled with green lines, and uncap my fountain pen, the one my mother gave me for my sixteenth birthday. It’s also crimson and feels heavy in my hand. I fill an old glass inkwell that I found on a desk in the study hall with black ink from a bottle. The acrid smell lingers in the air. It is the smell of a writer. I start at the beginning and put a number in the top right corner of each page. There are 155 pages, and I’m going to write on both sides. Three hundred and ten pages, that should be enough.

It took me a long time to get used to school, not to feel that everyone was looking at me and feeling sorry for me all the time. They hated feeling sorry for me. I think I’ll be able to be happy this year, sharing a suite with Lucy. That was my dream. Next year I have to think about college. I’ll have to start all over again.

I can’t believe how lucky we were. I chose a low number in the lottery, and we got our first choice. My room is larger, but Lucy’s has a fireplace, and we have our own bathroom between the two rooms. It’s so private and spacious. We can go into each other’s rooms whenever we want, and Mrs. Halton will never know. We just have to make sure that we are quiet and neat and don’t make her think we are the type to cause trouble. No one ever thinks Lucy is the type to cause trouble. She’s too sweet. Last year, Mrs. Dunlap was all over us, barging in during quiet hour to make sure we were alone. I hated that. This year we’ve arranged everything much better.

I don’t want this year ever to end.

I’m going to stay in my room until Lucy comes. I don’t want to see anyone else, only her.

The door.

It wasn’t Lucy. The new girl from across the corridor came over. It’s strange to have a new girl in the eleventh grade. And she’s managed to get a big room by herself with a bathroom and a fireplace. Everyone but Sofia is together on one corridor this year. Sofia wanted a single, and she didn’t have a good number. She had to settle for a small room in the front, but at least it’s just around the corner from us. Only the rooms on the second and third floors have fireplaces. Usually the new girls get the tiny maids’ rooms on the fourth floor. That’s all that’s left after everyone else chooses. They’re stuck up there with the eighth and ninth graders and Mac. Charley came up with that nickname for her. Mrs. McCallum looks like an old bulldog. The new girl is probably rich, and Miss Rood is trying to impress her parents.

I often think about what it was like when the Residence was a hotel. Rich guests came here for a “rest cure,” whatever that is. They rode ponies on the playing fields and played croquet and took afternoon tea on the porches and danced in the assembly room after dinner.

In a way nothing has changed since then, except that it’s full of girls.

The first time I drove through the tall iron gates of the Brangwyn School with my mother and saw the Residence, I felt as if I had woken up in a dream. No, not a dream. Dreams aren’t real. I had entered a different time and place, of curved red roofs and gables, stone arches and tall brick chimneys, all topped with ornaments of greenish copper, like weapons on a battlefield, spears and lances and halberds. This wasn’t a school; it was a castle. It was winter, and the playing fields and long, sweeping driveway were covered with snow. The snow made the fields look immense, endless.

Everything about school—the uniforms, the formal meals, the bells, the rules—was like the red roofs and copper spikes: elaborate and confusing. I didn’t know how I could get used to it. I thought I would leave before that happened. Then one day, someone said, “I’ll meet you on the Landing during break,” and even though there were staircases and landings all over the school, I knew exactly which landing she meant, the one behind the library. I didn’t have to look at her with a frantic blank stare.

The new girl’s name is Ernessa Bloch. She’s quite pretty, with long, dark, wavy hair, pale skin, deep red lips, and black eyes. Only her nose is too large and curves down at the end. Pretty is actually too girlish a word for her. Maybe that’s because of her manner; she’s very polite but not at all shy. She doesn’t speak with an accent, but there’s something foreign about her. She only stayed for a minute. She wanted to know what time we had to be up in the morning and if breakfast was compulsory. I offered to sign her in tomorrow because she said she was totally exhausted from her long trip. Her answer: “If it suits you.”

At last. This must be Lucy!

September 11

Sofia came running into my room last night after dinner. “There’s a man teaching English,” she said. “And he’s a poet!”

His name is Mr. Davies. I have him for “Beyond Belief: Writers of the Supernatural.” It was my first choice for electives this semester, but I don’t care about having a man for a teacher. All the other girls are going nuts. The ones who didn’t get into his classes are so jealous of us. I remember once Miss Watson brought a man to school, and nobody talked about anything else all day. Dora is in the “Age of Abstraction.” She’s going to read all kinds of heavy things like Dostoyevsky and Gide. I’m glad she’s not in my class.

Sofia said, “You’re in his class and you don’t care? That’s supernatural.”

He is good-looking, with medium-length brown hair and a moustache. He’s in his thirties and married. He wears a wedding ring. After one class, Claire is madly in love with him. There was a pile of poetry books on his desk, and the top one was the collected poems of Dylan Thomas.

Claire whispered to me, “You can tell him that your father was a famous poet, before he killed himself.”

She’s a stupid cow.

“He wasn’t famous,” was all I said.

She’s jealous of me because her father is just a boring lawyer. She thinks that if her father were a poet, Mr. Davies would fall in love with her. Besides, my father wasn’t just a poet; he also worked in a bank. He used to call poetry his hobby.

September 12

I have decided to write at least one page in my journal every day, like doing calisthenics. I’ll do it first thing during quiet hour. That way I won’t forget. I’ll write on weekends, too. I want to write about what happens to me during the day—what I have to do for homework, what’s for dinner, the score of my hockey game, who’s getting on my nerves. No dreaming about boyfriends or anything. I want it to be a record. I’ll be able to read it later and know exactly what happened to me when I was sixteen.

I’m going to practice the piano at the same time every day, during my free period right before lunch. I’ve been working on the same Mozart sonata for almost a year, and I still can’t play it the way I want to. I wish I could sit down at the piano and toss off the music without any effort. Instead I have to work so hard. Sometimes I’ll play a piece really well, but then it almost feels as if it’s not me playing. Miss Simpson says I have to work on my concentration. It’s true that my mind wanders when I play. I try to concentrate, but after a few minutes, I forget about the music and I’m wondering what’s for lunch.

Anyway, the first three days have been perfect.

September 15

I broke my resolution, but that doesn’t matter. No one is looking over my shoulder. I’ve been really busy. All my teachers loaded on the homework right from the first class. Lucy is already totally overwhelmed. She’s hopeless at chemistry. How is she going to make it through the whole year?

Nothing much happened anyway. I signed up for hockey again, even though Miss Bobbie will never move me up from B squad. It was hard enough to get onto B squad. I’m only there because I’m in eleventh grade. She likes the girls with long, straight, blond hair, the day student types. Not a Jew and a boarder! No matter how hard I practice, I’ll never move up. Even though I expected to see my name exactly where it appeared, I was still disappointed when they put up the lists on the Athletic Association bulletin board. And there was Lucy on A squad. She’d be there without doing anything. Of course Miss Bobbie likes Lucy. She’s the goddess of field hockey. If she weren’t my friend, I would hate her. She came up and put her arm around me and whispered in my ear, “Don’t cry. When she sees how good you are, she’ll move you up.”

What a stupid name, Miss Bobbie. Her real name is Miss Roberts. It’s pathetic for an old woman with white hair and sagging skin to have a nickname. She always wears a plaid wool kilt with a matching sweater over a white shirt and navy blue knee socks that fall down in folds around her ankles. It’s like a uniform. I’d never wear a uniform if I didn’t have to. Sofia likes the uniform, for some strange reason, but then she also loves school.

I’m not going to let that old cow ruin my fall. I love to play hockey, to run up and down the field, out of breath, with my lungs aching and the smell of dry leaves in the air. The light fades, and the players spread out across the field can barely see one another. They sink back into the darkness like ghosts. The white ball, the only thing that connects them, gleams on the grass. There’s the sound of the wooden stick smacking against the hard ball, the calls in the empty air, then the jarring, numbing feeling as I whack the ball down the long field and everyone takes off after it and disappears into the dusk. It’s beautiful. Even on B squad.

I’ve got to do some work before I go down to set up. I’m at Mrs. Davenport’s table. She lets us finish quickly, have coffee, and then get down to the Playroom for a smoke before study hour. That’s because she doesn’t eat much. She watches her weight. If you get at a table with Miss Bombay, she never lets you go without eating everything. It takes forever.

After dinner

Poor Lucy is stuck at Miss Bombay’s table. And she has to clear. That means we won’t have any time together in the Playroom after dinner. I haven’t been at Miss Bombay’s table since I came to school in ninth grade. It was bad enough that I came in the middle of the year, and then I was put at Miss Bombay’s table. I had to go away to school because my mother couldn’t have me around. She wanted to wallow in her own pain, alone. At night we sat down to dinner in silence. The only sounds were chewing and swallowing. If we had to speak, to ask for the salt or something, we would whisper and try not to stare at my father’s empty place. Every night I would think, I can’t stand to have another dinner with her. Then I got to school, and it was even worse. I was terrified of everything: the other boarders, the corridor teachers, the gym teachers, Miss Rood, all the rules and bells. I couldn’t even find my way around the school. One night I ran away from the other girls who gathered at the top of the stairs to go down to dinner together and came down the back stairs by the music practice rooms. I had no idea where I was. I stood in the dark hallway and cried. No one heard me. I could have been dead. At the table, as we stood for grace, I couldn’t stop staring at Miss Bombay. Her legs were so big and her ankles so swollen that her calves seemed to go right into her shoes, like thick wooden pegs. Her ankles and calves were wrapped up in ace bandages. She lowered herself slowly into her chair, clutching the edge of the table for support, and sighed with relief when she sat down. I was too petrified to eat. The room was flooded with the sounds of voices and clanking silverware, which got louder as dinner went on. There were conversations all around me. Girls jumped up and delivered the food from a cart, then ran around the table to clear away the plates and threw them back onto the cart. I looked up. My plate was still covered with food, there was a bite of lamb in my mouth, and I found the table had grown silent and everyone was staring at me. I couldn’t move my jaw to chew.

“Don’t hurry, dear,” said Miss Bombay. “Finish your meal.”

“Hurry up,” whispered the girl sitting next to me. “We want to have a smoke.”

I managed to squeak, “Done.”

“Go on now, finish up,” insisted Miss Bombay.

“No, I’m finished,” I said. Only my fear of the other girls made me speak louder.

Miss Bombay sat there without saying a word. I felt that if she made me finish, with everyone staring at me as I choked down each bite, I wouldn’t be able to stay at school. When she finally told the girls to clear, I was drenched in sweat, and my legs were trembling under the table. The worst part was that dessert was angel food cake with whipped cream. I wanted a piece so much, and Miss Bombay kept offering me one, but I kept shaking my head. Then I heard Miss Bombay whisper to one of the older girls, “The poor child is still in a state of shock.” Nothing could have been worse than those words. I wished I’d taken some dessert and my mouth was stuffed with the soft sweet cake like all the other girls sitting around the table, who seemed to stop chewing at once and stare at me again. This time not with annoyance but with disgusting pity in their eyes.

Now I’m one of those older girls. I hurry through dinner and go down for a smoke afterward. I have lots of friends, and no one stares. I always take a big piece of angel food cake.

When Dr. Karl Wolff first suggested publishing the journal that I kept during my junior year in boarding school, I thought I hadn’t heard him correctly. He’s been interested in me—or maybe I should say my case—since I was under his psychiatric care, and we talk on the phone every year or so. But I hadn’t seen the journal since I handed it over to him in the hospital thirty years ago, and we discussed it on only one occasion, when he made it clear I needed to put that period of my life behind me. Giving up writing in the journal was a first step.

My instinctive response to publication was to say no. I didn’t write the journal with the intention of having anyone else read it. And Dr. Wolff kept it only because of a promise he made to my mother before I left the hospital. I wrote it to preserve my sixteen-year-old self. Or at least that’s what I thought at the time. Besides, I have a daughter who is the same age I was when I kept this journal, and I want to protect her. I don’t feel that she needs to know everything about me.

Dr. Wolff reassured me. All the names would be changed. It would be impossible to recognize me in the person of the narrator. It would even be difficult to recognize the school. Above all, he felt the journal would be an invaluable addition to the literature on female adolescence at a time when risk-taking behavior has reached epidemic proportions. He happened to reread it while packing up his office before retirement and was struck by how convincing my writing was.

I’m not sure I agree with him. But I have always been intrigued by the journals that girls keep. They are like dollhouses. Once you look inside them, the rest of the world seems very far away, even unbelievable. If only we had the power to leap outside ourselves at such moments, we would spare ourselves so much pain and fear. I’m not talking about truth or falsehood but about surviving.

I agreed to Dr. Wolff’s suggestion with reservations. If, after reading my journal, I felt he was right, I would allow him to arrange for its publication. Dr. Wolff also asked me to write an afterword, as a kind of closure on the experience. He felt it was relatively rare for someone suffering from borderline personality disorder complicated by depression and psychosis to recover and never have another “episode,” as he so kindly put it. He was sure my reactions to the journal would be illuminating.

I can’t begin to judge that. When I opened this notebook, I found the razor blade I had hidden among the pages so long ago. Dr. Wolff had kept it as part of the “clinical picture,” as he explained. It looked utterly incongruous. It was just a razor blade. And the words on the page were just that—words in a familiar handwriting.

To anyone who wonders whether it’s possible to survive adolescence, that’s as much as I can offer of reassurance.

September

September 10

My mother dropped me off at two. Practically everyone is back. Except for Lucy. I can’t wait for her to come so that we can unpack together. I’m going to write in my journal until she’s here.

After my mother left, I felt an emptiness in my stomach that spread up through my throat to the back of my eyes. I didn’t cry, even though I probably would have felt better afterward. I needed to hold on to that feeling, that pain. If Lucy had been here, she would have distracted me. I had a moment of panic when I said good-bye to my mother. I almost begged her not to leave me here. It’s so strange. I’ve been looking forward to school for the past month. I was even excited when I got my new uniforms in the mail. The light blue spring skirt was as stiff as cardboard. I had to wash it before I could wear it. I’m glad I’m not a day student, worried about how I look on the train ride home. They sneak into the bathroom at the station and put on makeup and change from their saddle shoes into loafers, in case they run into boys they know on the train. I’ve seen them waiting for the train with their skirts hiked above their knees, and it’s hard to tell that they are wearing a uniform. We boarders couldn’t care less if we look like nurses.

Now that I’m here, I want to run away.

I’m always afraid to leave my mother. I’m afraid that I’ll never see her again. I want to run after her like a little girl, grab onto her skirt, grope for her hand, sniffle. Instead I stand very stiff and don’t say a word. “Can’t you at least say good-bye?” she says. After a few days, I get caught up in school. Then I’m glad to be away from her, even though she’s all I have left. I like to get letters from her, but I hate it when she calls. I never call her. Her voice is so heavy. It pulls me down. I’m always scared when I’m called to the phone. It’s incredibly hard for me to put the receiver to my ear. It wants to swallow me. I’m struggling to lift it, while the person on the other end is hanging in space, waiting for my voice.

From my window, I watched my mother speed down the drive. I lost sight of her car behind the Workshop. When she turned left onto the avenue, I could see it again, a streak of blue flashing through the black fence. And then she was gone. My mother always drives too fast; she doesn’t care what happens to her. Lucy’s mother would never drive like that.

I stood at the window for a long time. Then I turned around and looked at my room, my new room, with my trunk and bags and boxes piled up in the middle of the floor. It isn’t as wonderful as I had thought it would be all summer long. The walls are dirty. The girl who lived here last year left smudged black fingerprints in odd places. There’s nothing on the floor. Under the window is a chair with wooden arms, covered in tan and pink flowered material. It’s not very inviting. I think I’ll put some pillows on the sill and turn it into a window seat. I thought it would be the best room in the Residence. When I’ve unpacked and Lucy is next door, it will be different.

I got tired of waiting for Lucy, so I took a walk up to the train station. In the stationery store next to the drugstore, I found an old French composition book with a mottled crimson cover and a thick black spine, like a real book, but with blank pages. Somehow it ended up in the back of the store, forgotten. I grabbed it and walked up to the register, hugging it to my chest, afraid someone might snatch it away from me. It’s exactly like the journals my father used to keep. It was a sign, and I had to buy it. Now I’m going to fill it with words, the way he filled his notebooks: the pages, the margins, the endpapers all covered with little notes that made no sense to anyone else. I won’t tell anyone about it, not even Lucy.

I read the Claudine books over the summer. They were a replacement for school, which I missed so much. I hope the words flow from my pen onto the paper the way they did for Colette: the exact words I need. I’ve got Claudine at School on my desk, for inspiration. She knows what it’s like to be shut up in a place like this, where all your emotions are focused on the girls around you, where you dream of a boyfriend but only feel comfortable with your arm around another girl’s waist.

Already I’ve put too many sad thoughts down on these pages. I have to start all over again, very slowly and carefully. Everything has to be perfect. I’m not in a hurry. First, I open the notebook on my desk, flatten the smooth pages ruled with green lines, and uncap my fountain pen, the one my mother gave me for my sixteenth birthday. It’s also crimson and feels heavy in my hand. I fill an old glass inkwell that I found on a desk in the study hall with black ink from a bottle. The acrid smell lingers in the air. It is the smell of a writer. I start at the beginning and put a number in the top right corner of each page. There are 155 pages, and I’m going to write on both sides. Three hundred and ten pages, that should be enough.

It took me a long time to get used to school, not to feel that everyone was looking at me and feeling sorry for me all the time. They hated feeling sorry for me. I think I’ll be able to be happy this year, sharing a suite with Lucy. That was my dream. Next year I have to think about college. I’ll have to start all over again.

I can’t believe how lucky we were. I chose a low number in the lottery, and we got our first choice. My room is larger, but Lucy’s has a fireplace, and we have our own bathroom between the two rooms. It’s so private and spacious. We can go into each other’s rooms whenever we want, and Mrs. Halton will never know. We just have to make sure that we are quiet and neat and don’t make her think we are the type to cause trouble. No one ever thinks Lucy is the type to cause trouble. She’s too sweet. Last year, Mrs. Dunlap was all over us, barging in during quiet hour to make sure we were alone. I hated that. This year we’ve arranged everything much better.

I don’t want this year ever to end.

I’m going to stay in my room until Lucy comes. I don’t want to see anyone else, only her.

The door.

It wasn’t Lucy. The new girl from across the corridor came over. It’s strange to have a new girl in the eleventh grade. And she’s managed to get a big room by herself with a bathroom and a fireplace. Everyone but Sofia is together on one corridor this year. Sofia wanted a single, and she didn’t have a good number. She had to settle for a small room in the front, but at least it’s just around the corner from us. Only the rooms on the second and third floors have fireplaces. Usually the new girls get the tiny maids’ rooms on the fourth floor. That’s all that’s left after everyone else chooses. They’re stuck up there with the eighth and ninth graders and Mac. Charley came up with that nickname for her. Mrs. McCallum looks like an old bulldog. The new girl is probably rich, and Miss Rood is trying to impress her parents.

I often think about what it was like when the Residence was a hotel. Rich guests came here for a “rest cure,” whatever that is. They rode ponies on the playing fields and played croquet and took afternoon tea on the porches and danced in the assembly room after dinner.

In a way nothing has changed since then, except that it’s full of girls.

The first time I drove through the tall iron gates of the Brangwyn School with my mother and saw the Residence, I felt as if I had woken up in a dream. No, not a dream. Dreams aren’t real. I had entered a different time and place, of curved red roofs and gables, stone arches and tall brick chimneys, all topped with ornaments of greenish copper, like weapons on a battlefield, spears and lances and halberds. This wasn’t a school; it was a castle. It was winter, and the playing fields and long, sweeping driveway were covered with snow. The snow made the fields look immense, endless.

Everything about school—the uniforms, the formal meals, the bells, the rules—was like the red roofs and copper spikes: elaborate and confusing. I didn’t know how I could get used to it. I thought I would leave before that happened. Then one day, someone said, “I’ll meet you on the Landing during break,” and even though there were staircases and landings all over the school, I knew exactly which landing she meant, the one behind the library. I didn’t have to look at her with a frantic blank stare.

The new girl’s name is Ernessa Bloch. She’s quite pretty, with long, dark, wavy hair, pale skin, deep red lips, and black eyes. Only her nose is too large and curves down at the end. Pretty is actually too girlish a word for her. Maybe that’s because of her manner; she’s very polite but not at all shy. She doesn’t speak with an accent, but there’s something foreign about her. She only stayed for a minute. She wanted to know what time we had to be up in the morning and if breakfast was compulsory. I offered to sign her in tomorrow because she said she was totally exhausted from her long trip. Her answer: “If it suits you.”

At last. This must be Lucy!

September 11

Sofia came running into my room last night after dinner. “There’s a man teaching English,” she said. “And he’s a poet!”

His name is Mr. Davies. I have him for “Beyond Belief: Writers of the Supernatural.” It was my first choice for electives this semester, but I don’t care about having a man for a teacher. All the other girls are going nuts. The ones who didn’t get into his classes are so jealous of us. I remember once Miss Watson brought a man to school, and nobody talked about anything else all day. Dora is in the “Age of Abstraction.” She’s going to read all kinds of heavy things like Dostoyevsky and Gide. I’m glad she’s not in my class.

Sofia said, “You’re in his class and you don’t care? That’s supernatural.”

He is good-looking, with medium-length brown hair and a moustache. He’s in his thirties and married. He wears a wedding ring. After one class, Claire is madly in love with him. There was a pile of poetry books on his desk, and the top one was the collected poems of Dylan Thomas.

Claire whispered to me, “You can tell him that your father was a famous poet, before he killed himself.”

She’s a stupid cow.

“He wasn’t famous,” was all I said.

She’s jealous of me because her father is just a boring lawyer. She thinks that if her father were a poet, Mr. Davies would fall in love with her. Besides, my father wasn’t just a poet; he also worked in a bank. He used to call poetry his hobby.

September 12

I have decided to write at least one page in my journal every day, like doing calisthenics. I’ll do it first thing during quiet hour. That way I won’t forget. I’ll write on weekends, too. I want to write about what happens to me during the day—what I have to do for homework, what’s for dinner, the score of my hockey game, who’s getting on my nerves. No dreaming about boyfriends or anything. I want it to be a record. I’ll be able to read it later and know exactly what happened to me when I was sixteen.

I’m going to practice the piano at the same time every day, during my free period right before lunch. I’ve been working on the same Mozart sonata for almost a year, and I still can’t play it the way I want to. I wish I could sit down at the piano and toss off the music without any effort. Instead I have to work so hard. Sometimes I’ll play a piece really well, but then it almost feels as if it’s not me playing. Miss Simpson says I have to work on my concentration. It’s true that my mind wanders when I play. I try to concentrate, but after a few minutes, I forget about the music and I’m wondering what’s for lunch.

Anyway, the first three days have been perfect.

September 15

I broke my resolution, but that doesn’t matter. No one is looking over my shoulder. I’ve been really busy. All my teachers loaded on the homework right from the first class. Lucy is already totally overwhelmed. She’s hopeless at chemistry. How is she going to make it through the whole year?

Nothing much happened anyway. I signed up for hockey again, even though Miss Bobbie will never move me up from B squad. It was hard enough to get onto B squad. I’m only there because I’m in eleventh grade. She likes the girls with long, straight, blond hair, the day student types. Not a Jew and a boarder! No matter how hard I practice, I’ll never move up. Even though I expected to see my name exactly where it appeared, I was still disappointed when they put up the lists on the Athletic Association bulletin board. And there was Lucy on A squad. She’d be there without doing anything. Of course Miss Bobbie likes Lucy. She’s the goddess of field hockey. If she weren’t my friend, I would hate her. She came up and put her arm around me and whispered in my ear, “Don’t cry. When she sees how good you are, she’ll move you up.”

What a stupid name, Miss Bobbie. Her real name is Miss Roberts. It’s pathetic for an old woman with white hair and sagging skin to have a nickname. She always wears a plaid wool kilt with a matching sweater over a white shirt and navy blue knee socks that fall down in folds around her ankles. It’s like a uniform. I’d never wear a uniform if I didn’t have to. Sofia likes the uniform, for some strange reason, but then she also loves school.

I’m not going to let that old cow ruin my fall. I love to play hockey, to run up and down the field, out of breath, with my lungs aching and the smell of dry leaves in the air. The light fades, and the players spread out across the field can barely see one another. They sink back into the darkness like ghosts. The white ball, the only thing that connects them, gleams on the grass. There’s the sound of the wooden stick smacking against the hard ball, the calls in the empty air, then the jarring, numbing feeling as I whack the ball down the long field and everyone takes off after it and disappears into the dusk. It’s beautiful. Even on B squad.

I’ve got to do some work before I go down to set up. I’m at Mrs. Davenport’s table. She lets us finish quickly, have coffee, and then get down to the Playroom for a smoke before study hour. That’s because she doesn’t eat much. She watches her weight. If you get at a table with Miss Bombay, she never lets you go without eating everything. It takes forever.

After dinner

Poor Lucy is stuck at Miss Bombay’s table. And she has to clear. That means we won’t have any time together in the Playroom after dinner. I haven’t been at Miss Bombay’s table since I came to school in ninth grade. It was bad enough that I came in the middle of the year, and then I was put at Miss Bombay’s table. I had to go away to school because my mother couldn’t have me around. She wanted to wallow in her own pain, alone. At night we sat down to dinner in silence. The only sounds were chewing and swallowing. If we had to speak, to ask for the salt or something, we would whisper and try not to stare at my father’s empty place. Every night I would think, I can’t stand to have another dinner with her. Then I got to school, and it was even worse. I was terrified of everything: the other boarders, the corridor teachers, the gym teachers, Miss Rood, all the rules and bells. I couldn’t even find my way around the school. One night I ran away from the other girls who gathered at the top of the stairs to go down to dinner together and came down the back stairs by the music practice rooms. I had no idea where I was. I stood in the dark hallway and cried. No one heard me. I could have been dead. At the table, as we stood for grace, I couldn’t stop staring at Miss Bombay. Her legs were so big and her ankles so swollen that her calves seemed to go right into her shoes, like thick wooden pegs. Her ankles and calves were wrapped up in ace bandages. She lowered herself slowly into her chair, clutching the edge of the table for support, and sighed with relief when she sat down. I was too petrified to eat. The room was flooded with the sounds of voices and clanking silverware, which got louder as dinner went on. There were conversations all around me. Girls jumped up and delivered the food from a cart, then ran around the table to clear away the plates and threw them back onto the cart. I looked up. My plate was still covered with food, there was a bite of lamb in my mouth, and I found the table had grown silent and everyone was staring at me. I couldn’t move my jaw to chew.

“Don’t hurry, dear,” said Miss Bombay. “Finish your meal.”

“Hurry up,” whispered the girl sitting next to me. “We want to have a smoke.”

I managed to squeak, “Done.”

“Go on now, finish up,” insisted Miss Bombay.

“No, I’m finished,” I said. Only my fear of the other girls made me speak louder.

Miss Bombay sat there without saying a word. I felt that if she made me finish, with everyone staring at me as I choked down each bite, I wouldn’t be able to stay at school. When she finally told the girls to clear, I was drenched in sweat, and my legs were trembling under the table. The worst part was that dessert was angel food cake with whipped cream. I wanted a piece so much, and Miss Bombay kept offering me one, but I kept shaking my head. Then I heard Miss Bombay whisper to one of the older girls, “The poor child is still in a state of shock.” Nothing could have been worse than those words. I wished I’d taken some dessert and my mouth was stuffed with the soft sweet cake like all the other girls sitting around the table, who seemed to stop chewing at once and stare at me again. This time not with annoyance but with disgusting pity in their eyes.

Now I’m one of those older girls. I hurry through dinner and go down for a smoke afterward. I have lots of friends, and no one stares. I always take a big piece of angel food cake.

Descriere

At an exclusive girls' boarding school, a 16-year-old girl records her most intimate thoughts in a diary. The object of her growing obsession is her roommate, Lucy, and their new and disturbing classmate Ernessa. At the center of the diary is the question that haunts all who read it: Is Ernessa really a vampire?

Notă biografică

Rachel Klein