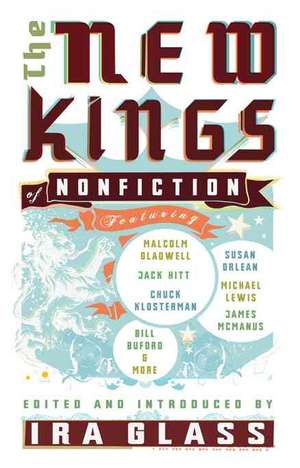

The New Kings of Nonfiction

Editat de Ira Glassen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2007 – vârsta de la 18 ani

A collection of stories-some well known, some more obscure- capturing some of the best storytelling of this golden age of nonfiction.

An anthology of the best new masters of nonfiction storytelling, personally chosen and introduced by Ira Glass, the producer and host of the award-winning public radio program This American Life.

These pieces-on teenage white collar criminals, buying a cow, Saddam Hussein, drunken British soccer culture, and how we know everyone in our Rolodex-are meant to mesmerize and inspire.

An anthology of the best new masters of nonfiction storytelling, personally chosen and introduced by Ira Glass, the producer and host of the award-winning public radio program This American Life.

These pieces-on teenage white collar criminals, buying a cow, Saddam Hussein, drunken British soccer culture, and how we know everyone in our Rolodex-are meant to mesmerize and inspire.

Preț: 137.30 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 206

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.27€ • 27.38$ • 21.75£

26.27€ • 27.38$ • 21.75£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781594482670

ISBN-10: 1594482675

Pagini: 455

Dimensiuni: 129 x 202 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Ediția:Riverhead Trade.

Editura: Riverhead Books

ISBN-10: 1594482675

Pagini: 455

Dimensiuni: 129 x 202 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Ediția:Riverhead Trade.

Editura: Riverhead Books

Notă biografică

Ira Glass is the producer and host of the award-winning radio and television program "This American Life".

Extras

Introduction Years ago, when I worked for public radio’s daily news shows, I put together this story about a guy named Jack Davis. He was a Rush Limbaugh fan and a proud Republican, and he’d set out on an unusual mission. He wanted to go into the Chicago public housing projects to instruct the children there in the value of hard work and entrepreneurship. He’d do this with vegetables. His plan was to teach the kids at the Cabrini Green projects to grow high-end produce, they’d sell their crop to the fancy restaurants that are just blocks from Cabrini, and this would be a valuable life lesson in the joys of market capitalism.

So Jack set up a garden in the middle of the high-rises, and for the first few years, it didn’t go so well. Jack was an accountant from the white suburbs and he didn’t relate to the kids or understand the culture of the projects. He made a lot of parents mad. A kid would miss a day’s work in the vegetable garden and Jack would dock his pay, to teach the consequences of sloth. Then all the windows in Jack’s truck would get smashed. Jack’s message was not getting through.

Hoping to turn this around, he enlisted this guy named Dan Underwood, who lived in Cabrini and whose children had been working in the garden. Everyone in the projects seemed to know Dan. He ran a double-Dutch jump-rope team for Cabrini kids that was ranked number one in the city, and a drum and color-guard squad, and martial arts classes. Kids loved Dan. He was fatherly. He was fun.

And while Jack was committed to the idea that they should run the vegetable garden like a real business, Dan saw it as just another afterschool program. “These are children,” he told me. “It’s not like an adult coming to work at, you know, 8:00 and getting off at 4:30, and ‘If you don’t come, you don’t get no money.’ That won’t work, not with a child.” When a kid didn’t show up to pick tomatoes, Dan would go to the family and find out why. He’d buy the kids pizza and take them on trips and get them singing in the van. What they needed was no mystery, as far as he was concerned. They were normal kids growing up in an unusually tough neighborhood, and they needed what any kid needs: some attention and some fun.

And sometimes, when he and Jack argued over how to run the program, they were both aware—uncomfortably aware, I think—how they were reenacting, in a vegetable garden surrounded by dingy high-rises, a bigger national debate. The white suburbanite was stomping around insisting that the project kids get a job and show up on time and not be coddled anymore, all for their own good, all to make them self-sufficient. The black guy was telling the interloper that he didn’t know what he was talking about. A little coddling might be better for these kids than an enhanced appreciation of the work ethic and the free market.

When I was working on this story I thought that Jack and Dan would’ve made a great ’70s TV show, one of those Norman Lear sitcoms where every week something happens to make all the characters argue about the big issues of the day. Sadly, we were twenty years too late for that, and Norman Lear had already set a show—Good Times—in Cabrini Green. One interesting thing about this story was how my officemate at the time hated it. Or maybe hate’s too strong a word. He was suspicious of the story. And he was incredulous at how it seemed to lay out like a perfect little fable about modern America. “Are you making these stories up?” I remember him asking.

But I don’t see anything wrong with a piece of reporting turning into a fable. In fact, when I’m researching a story and the real-life situation starts to turn into allegory—as it did with Dan and Jack—I feel incredibly lucky, and do everything in my power to expand that part of the story. Everything suddenly stands for something so much bigger, everything has more resonance, everything’s more engaging. Turning your back on that is rejecting tools that could make your work more powerful. But for a surprising number of reporters, the stagecraft of telling a story—managing its fable-like qualities—is not just of secondary concern, but a kind of mumbo jumbo that serious-minded people don’t get too caught up in. Taking delight in this part of the job, from their perspective, has little place in our important work as journalists. Another public radio officemate at that time—a Columbia University School of Journalism grad—would come back from the field with funny, vivid anecdotes she’d tell us in the hallway. Few of them ever appeared in her reports, which were dry as bones and hard to listen to.

She always had the same explanation for why she’d omit the entertaining details: “I thought that would be putting myself in the story.” As if being interesting and expressing any trace of a human personality would somehow detract from the nonstop flow of facts she assumed her listeners were craving. There’s a whole class of reporters—especially ones who went to journalism school, by the way—who have a strange kind of religious conviction about this. They actually get indignant; it’s an affront to them when a reporter tries to amuse himself and his audience.

I say phooey to that. This book says phooey to that.

Most of the stories in this book come from a stack of favorite writing that I’ve kept behind my desk for years. It started as a place to toss articles I simply didn’t want to throw away, and it’s a mess. Old photocopies of photocopies. Pages I’ve torn from magazines and stapled together. Random issues of a Canadian magazine a friend edited for a while. Now and then, in working on a radio story with someone, I’ll want to explain a certain kind of move they could try, or someone just needs inspiration. They need to see just how insanely good a piece of writing can be, and shoot for that. That’s when I go to the stack.

As far as I’m concerned, we’re living in an age of great nonfiction writing, in the same way that the 1920s and ’30s were a golden age for American popular song. Giants walk among us. Cole Porters and George Gershwins and Duke Ellingtons of nonfiction storytelling. They’re trying new things and doing pirouettes with the form. But nobody talks about it that way.

I don’t pretend that the writers in my stack of stories are representative of a movement or a school of writing or anything like that. But they generally share a few traits. First and foremost, they’re incredibly good reporters. And like the best reporters, they either find a new angle on something we all know about already, or—more often—they take on subjects that nobody else has figured out are worthy of reporting. They’re botanists in search of plants nobody’s given a name to yet. Take Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker story “Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg,” which at first reads like any other magazine story, until you take a moment to realize what it’s about, which is nothing less than the question “how does everyone know everyone they know?” Or Lee Sandlin’s story, which is attempting to redefine everything we think about World War II and, while he’s at it, all other wars as well. Or Michael Pollan’s story, where he buys a steer to illustrate in the most vivid way possible a thousand details most of us don’t know about where our meat comes from. Or Mark Bowden’s story, which addresses a very simple question, a question that’s so simple that once you’ve heard it, you wonder why you’ve never heard anybody else ask it: what was Saddam Hussein really like?

And these writers are all entertainers, in the best sense of the word. I know that’s not how we usually talk about great reporting, but it’s a huge part of all these stories. Great scenes, great characters, great moments. Often they’re funny. There’s a cheerful embracing of life in this kind of journalism, and a curiosity about the world. What hits me most when I reread Gladwell’s story is not his skill at laying out a series of very enjoyable anecdotes and his even greater skill at deploying scientific research that sheds light on those anecdotes. What hits me most is how the article could be half the length and still hit all its big ideas, and it’s only longer because Gladwell has found so many things that interest and amuse him, and that’s the engine that drives the whole enterprise. There’s a whole section of the article about actors and Kevin Bacon and Burgess Meredith that actually repeats an idea he illustrates elsewhere. And pretty much everything in the story after section five is, to my way of thinking, just there for fun. That includes Gladwell thinking through the consequences of his findings for affirmative-action programs, a scene of Gladwell trying to pin down the inner life of one of his super-connected interviewees, and—best of all—the completely improbable and utterly amazing story of how his protagonist, Lois Weisberg, hooked up with her second husband.

Finally, near the very end of the article, Gladwell is trying to explain once and for all why some of us know such an extraordinary number of people and, like a man writing a fable, he arrives at the moral of his story, which he points out is “the same lesson they teach in Sunday school.” Which is what I love about Gladwell. He stumbles onto some new phenomenon, and he’s trying his damnedest, for page after page, to think through what it means. And part of his mission is sharing the sheer pleasure in thinking it through. This is a special kind of pleasure, and another thing we don’t usually talk about when we talk about what makes a piece of journalism great. It’s the pleasure of discovery, the pleasure of trying to make sense of the world. Take this joyful passage from Jack Hitt’s story about a personal-injury lawsuit so big that the four thousand plaintiff s—just to keep their claims straight—actually had to write their own constitution. As Hitt notes, it’s nearly as long as the U.S. Constitution.

What first drew my attention was that absurd name. Stringfellow. Acid. Pits. Modern life rarely shunts nouns together with such Dickensian economy. After I first encountered that singular name in a newspaper article some four or five years ago, it began to appear in my life eerily, serendipitously. If I was in Washington, the Post had a short update; if in San Francisco, then the Chronicle. If, while dressing in a hotel, I caught an environmental lawyer on C-SPAN, then Stringfellow would be cited offhandedly and without explanation. One evening, seated at an intimate dinner party in New Haven, Connecticut, I casually mentioned my growing interest in String-fellow. Across the table a head turned and said, “I’ve worked on that case.” Then another guest spoke up. He, too, was indirectly involved. I was not following the case; it was pursuing me.

The newspaper reports I read created a sense of Cyclopean dimension: a specially constructed courtroom, private judges, secret negotiations, a quarter-million pages of pretrial documents, and legal processes of absurd intricacy. The case presented a problem unique in the history of American law. How does a court try four thousand cases that are generally similar but legally different? Judge Erik Kaiser came up with an innovative solution: he would bundle the four thousand plaintiffs into groups of roughly seventeen, and try the bundled cases consecutively. Consider the math: 4,000 divided by 17=235 trials. If each one lasted a little under a year—a conservative estimate—the entire process would be wrapped up in two centuries.

Two-thirds of the way into his story, it takes a remarkable turn, one I’ve rarely seen in any piece of reporting. There’s no way for me to explain this turn without actually revealing the spoiler so jump down to the next paragraph right now if you don’t want to know. Ready? Jack Hitt discovers that the premise of his story is completely wrong. Fantastic, right? Or here’s an excerpt from Bill Buford’s hilarious and disturbing book Among the Thugs, where he spends months with soccer hooligans in England.

The thing about reporting is that it is meant to be objective. It is meant to record and relay the truth of things, as if truth were out there, hanging around, waiting for the reporter to show up. Such is the premise of objective journalism. What this premise excludes, as any student of modern literature will tell you, is that slippery relative fact of the person doing the reporting, the modern notion that there is no such thing as the perceived without someone to do the perceiving, and that to exclude the circumstances surrounding the story is to tell an untruth. . . .

I do not want to tell an untruth and feel compelled, therefore, to note that at this moment, the reporter was aware that the circumstances surrounding his story had become intrusive and significant and that, if unacknowledged, his account of the events that follow would be grossly incomplete. And his circumstances were these: the reporter was very, very drunk.

That’s the will to entertain.

Part of what’s exciting about Among the Thugs is that Buford is so honest about what happens between him and his interviewees, especially the awkwardness he feels as an outsider in the midst of this tribe of drunk, violent men. They hate him, and they don’t trust him, and he doesn’t pretend otherwise. There’s a transparency to the reporting. Most of the book is Buford putting himself into one situation after another, and simply describing all the chance encounters he has along the way. It’s an inspiring book to read if you want to try your hand at reporting, because it makes the job seem so damned straightforward, and I can’t count the number of copies I’ve given away over the years to beginning journalists. Buford makes it clear how much of reporting is simply wandering from one place to another, talking to people and writing down what they say and trying to think of something, anything, that’ll shed some light on what’s happening in front of your face.

This explicitness about the process of reporting is true for many of the writers in this collection. It’s a shame this technique is forbidden to most daily newspaper reporters and broadcast journalists, because a lot of the power of these stories comes from the writers telling you step by step what they’re feeling and thinking, as they do their reporting. For example, here’s how Michael Lewis explains his interest in the story of a fifteen-year-old named Jonathan Lebed—a minor who got into trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission for trading stocks online: “When I first read the newspaper reports last fall, I didn’t understand them. It wasn’t just that I didn’t understand what the kid had done wrong; I didn’t understand what he had done.”

Much later in the story Lewis interviews the Chairman of the SEC about Lebed’s supposed crime, and he does something I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a reporter do in an interview with a government official. Lewis tells us what he’s thinking, moment by moment, as the SEC Chair trots out one unconvincing argument after another. It’s breathtaking, and skewers the guy in a way I’ve never seen before or since in an American newspaper. What’s even more breathtaking is that somehow, Lewis doesn’t come across as unfair. He doesn’t seem like a hothead, or someone with an agenda. He comes off as a curious, reasonable guy, the most reasonable guy in the room in fact, a guy who’s both annoyed and amused at the hokum being peddled. It’s done so deftly you don’t even realize how delicate it is, what he’s pulling off. Especially when you consider the big policy questions he’s juggling at the same time. In the middle of telling this great yarn, he’s actually explaining an entirely original way to look at the regulation of the stock market and online trading, an analysis he invented himself over the course of his reporting. And he’s made his explanation simple enough that people like you and me who may know absolutely nothing about the markets will understand what he’s talking about and why it matters at all.

Which brings me to my next point. What I’m about to say doesn’t apply to breaking news stories, which have their own rules and logic, but does apply to stories like the ones in this book, or on the radio show I host. When you’re writing stories like these, I think you’ve really only got two basic building blocks. You’ve got the plot of the story, and you’ve got the ideas the story is driving at. Usually the plot is the easy part. You do whatever research you can, you talk to lots of people, and you figure out what happened. It’s the ideas that kill you. What’s the story mean? What bigger truth about all of us does it point to? You can knock your head against a wall for days thinking that through.

The writers in this book are geniuses when it comes to the ideas. In fact usually their stories would have trouble existing at all, without the scaffolding of ideas they’ve erected to hold the thing up. And some of the moves they pull to deploy their ideas! There’s a section in Lawrence Weschler’s story “Shapinsky’s Karma” where every character in the story walks up to Weschler to tell him the meaning of the story he’s writing about Shapinksy. Some of them even offer titles for his story. Susan Orlean’s “The American Man, Age Ten” is a tour de force on this score, as she tries to think through what it means to be ten. She’s profiling a random suburban kid named Colin Duffy. I could almost pick any three sentences from the story at random and they’ll make my point, but this passage just kills me:

The girls in Colin’s class are named Cortnerd, Terror, Spacey, Lizard, Maggot, and Diarrhea. “They do have other names, but that’s what we call them,” Colin told me. “The girls aren’t very popular.”

“They are about as popular as a piece of dirt,” Japeth [Colin’s friend] said. “Or you know that couch in the classroom? That couch is more popular than any girl. A thousand times more.”

That is a very efficient way to explain a ten-year-old boy’s attitude toward girls. I love the overall tone she invents to write this story. It’s a voice that’s halfway between hers and his.

If Colin Duffy and I were to get married, we would have matching superhero notebooks. . . . We would eat pizza and candy for all of our meals. We wouldn’t have sex, but we would have crushes on each other and, magically, babies would appear in our home. We would win the lottery and then buy land in Wyoming, where we would have one of every kind of cute animal. All the while, Colin would be working in law enforcement—probably the FBI. Our favorite movie star, Morgan Freeman, would visit us occasionally. We would listen to the same Eurythmics song (“Here Comes the Rain Again”) over and over again and watch two hours of television every Friday night. We would both be good at football, have best friends, and know how to drive; we would cure AIDS and the garbage problem and everything that hurts animals. We would hang out a lot with Colin’s dad. For fun, we would load a slingshot with dog food and shoot it at my butt. We would have a very good life.

Much later in the story, Orlean states more explicitly some of her conclusions about Colin’s view of the world.

The collision in his mind of what he understands, what he hears, what he figures out, what popular culture pours into him, what he knows, what he pretends to know, and what he imagines makes an interesting mess. The mess oft en has the form of what he will probably think like when he is a grown man, but the content of what he is like as a little boy.

One thing I love about Weschler and Orlean (and, come to think of it, most of these writers) is their attitude toward the people they’re writing about. Weschler is clearly skeptical of his protagonist, Akumal. Orlean is not in agreement with her ten-year-old. But they try to get inside their protagonists’ heads with a degree of empathy that’s unusual. Theirs is a ministry of love, in a way we don’t usually discuss reporters’ feelings toward their subjects. Or at least, they’re willing to see what is lovable in the people they’re interviewing. (Weschler’s an interesting case when it comes to this, because he’s mildly annoyed by his main character for the early part of his story, and then comes to have an obvious and real affection for him.)

David Foster Wallace’s story kind of sneaks up on you in this regard. He’s writing about right-wing talk radio, which is, depending on how you look at it, either very easy or very hard to write about well, since it’s something everyone already has an opinion about. And aft er laying out a series of eye-opening details about how the whole talk industry actually works, at some point Wallace just starts to get very, very interested in the question of what sort of guy would be holding forth with these sorts of opinions on the radio. He then produces a set of unusually frank anecdotes and quotes to answer that question. The unusual honesty, by the way, is explained with this helpful footnote:

The best guess re Mr. Z.’s brutal on-record frankness is that either

(a) the host’s on- and off-air personas really are identical, or (b) he regards speaking to a magazine correspondent as just one more part of his job, which is to express himself in a maximally stimulating way.

Part of what’s most interesting about this story, I think, is Wallace’s attitude toward Mr. Z. When he analyzes what Mr. Z. says on the air, he questions some of the most basic premises of Mr. Z.’s occupation. But it’s all done in a way that’s somehow still sympathetic to the guy.

This empathetic mission gives the writing a warmth, and—not incidentally—it helps Wallace and all these writers get away with saying certain unflattering things about their subjects, because it’s clear the overall project of their writing is not a malicious or demeaning one. I like that. And as a reporter, I understand it. I have this experience when I interview someone, if it’s going well and we’re really talking in a serious way, and they’re telling me these very personal things, I fall in love a little. Man, woman, child, any age, any background, I fall in love a little. They’re sharing so much of themselves. If you have half a heart, how can you not?

Chuck Klosterman even makes Val Kilmer sympathetic. Klosterman is both an essayist and a reporter, and as an essayist, he has this fantastically agile brain. He tears through one idea after another with a speed and fierce confidence that I always find kind of inspiring. Some of the essays in his book Sex, Drugs and Cocoa Puff s I’ve read over and over, like the one explaining how Star Wars and Reality Bites are actually the same movie, and how that movie perfectly captures everything about Generation X, which is Klosterman’s generation. (“There are no myths about Generation X,” he writes. “It’s all true.”) When Klosterman does reporting, the superstructure of ideas and the aggressiveness with which he states those ideas are a big part of what makes the stories stand out. And the ideas are especially important when he writes about celebrities. I think celebrity journalism is one of the toughest assignments you can do, because the super-famous are usually guarded about what they reveal, and because they’ve been interviewed so many times before, what’s left for you to explore? Klosterman’s Val Kilmer story is a good example of someone taking a celebrity interview and creating a context and structure that gives the quotes and moments so much meaning. In general, Klosterman writes with a lot of sympathy for his subjects, while still simultaneously pointing out all sorts of things about them that they might find unflattering.

I wish there were a catchy name for stories like this. For one thing, it would’ve made titling this collection a lot easier. Sometimes people use the phrase “literary nonfiction” for work like this, but I’m a snob when it comes to that phrase. I think it’s for losers. It’s pretentious, for one thing, and it’s a bore. Which is to say, it’s exactly the opposite of the writing it’s trying to describe. Calling a piece of writing “literary nonfiction” is like daring you to read it.

In choosing stories for this book, I haven’t tried to include every great nonfiction writer who’s working right now, or even all my favorites. I ended up rereading dozens of essays and stories I’ve loved, some of them by regular contributors to the radio program, some by people I’ve admired from afar. In the end I returned to my original premise—to select journalism I’ve found myself talking about and recommending over the years. And I decided to stick with stories that are built around original reporting of one sort or another, not essays.

Some of these stories are very well-known; some barely known. There’s a whole class of stories I’ve included because the writers are trying to document such remarkable experiences they’ve had. Dan Savage tells how he got so sick of the homophobic policies of the Republican Party that he decided to join the party himself and became a delegate to their state convention, where he caused various sorts of trouble. Coco Henson Scales describes what happens inside a trendy New York restaurant and—even more interesting—inside her head as the hostess there. In her story, celebrities show up and perform exactly as you’d want them to, but never get to see in print. It is possibly the greatest New York Times “Styles Section” feature that will ever be written.

Jim McManus’s poker story is amazing because the facts shouldn’t lay out the way they do. He enters his first poker tournament—the World Series of Poker—to write about it for Harper’s magazine, and he ends up at the final table, pocketing a quarter-million dollars. This is the poker equivalent of showing up at the Olympics, never having competed on track or field, and taking home the bronze for the 100-meter dash. At one point, McManus squares off against one of his heroes, a guy whose poker manual he’d read and reread to prepare for the tournament, and—if that’s not enough—they end up playing one of the hands the guy wrote about in his book. “I’ve studied the passage so obsessively,” McManus writes, “I believe I can quote it verbatim.” His Harper’s article, by the way, was published two years before the full-blown poker craze hit America, which explains why he’s so patiently explaining rules and customs of the game that are now familiar to most high school students.

While this is the golden age of this kind of reporting and writing, it’s also a golden age for crap journalism. And for some of the most amazing technological advances for stuffing it down your throat. A lot of daily reporting and news “commentary” just reinforces everything we already think about the world. It lacks the sense of discovery, the curiosity, the uncorny, human-size drama that’s part of all these stories. A lot of daily reporting makes the world seem smaller and stupider.

In that environment, these stories are a kind of beacon. By making stories full of empathy and amusement and the sheer pleasure of discovering the world, these writers reassert the fact that we live in a world where joy and empathy and pleasure are all around us, there for the noticing. They make the world seem like an exciting place to live. I come out of them feeling like a better person—more awake and more aware and more appreciative of everything around me. That’s a hard thing for any kind of writing to accomplish. In times when the media can seem so clueless and beside the point, that’s a great comfort in itself.

So Jack set up a garden in the middle of the high-rises, and for the first few years, it didn’t go so well. Jack was an accountant from the white suburbs and he didn’t relate to the kids or understand the culture of the projects. He made a lot of parents mad. A kid would miss a day’s work in the vegetable garden and Jack would dock his pay, to teach the consequences of sloth. Then all the windows in Jack’s truck would get smashed. Jack’s message was not getting through.

Hoping to turn this around, he enlisted this guy named Dan Underwood, who lived in Cabrini and whose children had been working in the garden. Everyone in the projects seemed to know Dan. He ran a double-Dutch jump-rope team for Cabrini kids that was ranked number one in the city, and a drum and color-guard squad, and martial arts classes. Kids loved Dan. He was fatherly. He was fun.

And while Jack was committed to the idea that they should run the vegetable garden like a real business, Dan saw it as just another afterschool program. “These are children,” he told me. “It’s not like an adult coming to work at, you know, 8:00 and getting off at 4:30, and ‘If you don’t come, you don’t get no money.’ That won’t work, not with a child.” When a kid didn’t show up to pick tomatoes, Dan would go to the family and find out why. He’d buy the kids pizza and take them on trips and get them singing in the van. What they needed was no mystery, as far as he was concerned. They were normal kids growing up in an unusually tough neighborhood, and they needed what any kid needs: some attention and some fun.

And sometimes, when he and Jack argued over how to run the program, they were both aware—uncomfortably aware, I think—how they were reenacting, in a vegetable garden surrounded by dingy high-rises, a bigger national debate. The white suburbanite was stomping around insisting that the project kids get a job and show up on time and not be coddled anymore, all for their own good, all to make them self-sufficient. The black guy was telling the interloper that he didn’t know what he was talking about. A little coddling might be better for these kids than an enhanced appreciation of the work ethic and the free market.

When I was working on this story I thought that Jack and Dan would’ve made a great ’70s TV show, one of those Norman Lear sitcoms where every week something happens to make all the characters argue about the big issues of the day. Sadly, we were twenty years too late for that, and Norman Lear had already set a show—Good Times—in Cabrini Green. One interesting thing about this story was how my officemate at the time hated it. Or maybe hate’s too strong a word. He was suspicious of the story. And he was incredulous at how it seemed to lay out like a perfect little fable about modern America. “Are you making these stories up?” I remember him asking.

But I don’t see anything wrong with a piece of reporting turning into a fable. In fact, when I’m researching a story and the real-life situation starts to turn into allegory—as it did with Dan and Jack—I feel incredibly lucky, and do everything in my power to expand that part of the story. Everything suddenly stands for something so much bigger, everything has more resonance, everything’s more engaging. Turning your back on that is rejecting tools that could make your work more powerful. But for a surprising number of reporters, the stagecraft of telling a story—managing its fable-like qualities—is not just of secondary concern, but a kind of mumbo jumbo that serious-minded people don’t get too caught up in. Taking delight in this part of the job, from their perspective, has little place in our important work as journalists. Another public radio officemate at that time—a Columbia University School of Journalism grad—would come back from the field with funny, vivid anecdotes she’d tell us in the hallway. Few of them ever appeared in her reports, which were dry as bones and hard to listen to.

She always had the same explanation for why she’d omit the entertaining details: “I thought that would be putting myself in the story.” As if being interesting and expressing any trace of a human personality would somehow detract from the nonstop flow of facts she assumed her listeners were craving. There’s a whole class of reporters—especially ones who went to journalism school, by the way—who have a strange kind of religious conviction about this. They actually get indignant; it’s an affront to them when a reporter tries to amuse himself and his audience.

I say phooey to that. This book says phooey to that.

Most of the stories in this book come from a stack of favorite writing that I’ve kept behind my desk for years. It started as a place to toss articles I simply didn’t want to throw away, and it’s a mess. Old photocopies of photocopies. Pages I’ve torn from magazines and stapled together. Random issues of a Canadian magazine a friend edited for a while. Now and then, in working on a radio story with someone, I’ll want to explain a certain kind of move they could try, or someone just needs inspiration. They need to see just how insanely good a piece of writing can be, and shoot for that. That’s when I go to the stack.

As far as I’m concerned, we’re living in an age of great nonfiction writing, in the same way that the 1920s and ’30s were a golden age for American popular song. Giants walk among us. Cole Porters and George Gershwins and Duke Ellingtons of nonfiction storytelling. They’re trying new things and doing pirouettes with the form. But nobody talks about it that way.

I don’t pretend that the writers in my stack of stories are representative of a movement or a school of writing or anything like that. But they generally share a few traits. First and foremost, they’re incredibly good reporters. And like the best reporters, they either find a new angle on something we all know about already, or—more often—they take on subjects that nobody else has figured out are worthy of reporting. They’re botanists in search of plants nobody’s given a name to yet. Take Malcolm Gladwell’s New Yorker story “Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg,” which at first reads like any other magazine story, until you take a moment to realize what it’s about, which is nothing less than the question “how does everyone know everyone they know?” Or Lee Sandlin’s story, which is attempting to redefine everything we think about World War II and, while he’s at it, all other wars as well. Or Michael Pollan’s story, where he buys a steer to illustrate in the most vivid way possible a thousand details most of us don’t know about where our meat comes from. Or Mark Bowden’s story, which addresses a very simple question, a question that’s so simple that once you’ve heard it, you wonder why you’ve never heard anybody else ask it: what was Saddam Hussein really like?

And these writers are all entertainers, in the best sense of the word. I know that’s not how we usually talk about great reporting, but it’s a huge part of all these stories. Great scenes, great characters, great moments. Often they’re funny. There’s a cheerful embracing of life in this kind of journalism, and a curiosity about the world. What hits me most when I reread Gladwell’s story is not his skill at laying out a series of very enjoyable anecdotes and his even greater skill at deploying scientific research that sheds light on those anecdotes. What hits me most is how the article could be half the length and still hit all its big ideas, and it’s only longer because Gladwell has found so many things that interest and amuse him, and that’s the engine that drives the whole enterprise. There’s a whole section of the article about actors and Kevin Bacon and Burgess Meredith that actually repeats an idea he illustrates elsewhere. And pretty much everything in the story after section five is, to my way of thinking, just there for fun. That includes Gladwell thinking through the consequences of his findings for affirmative-action programs, a scene of Gladwell trying to pin down the inner life of one of his super-connected interviewees, and—best of all—the completely improbable and utterly amazing story of how his protagonist, Lois Weisberg, hooked up with her second husband.

Finally, near the very end of the article, Gladwell is trying to explain once and for all why some of us know such an extraordinary number of people and, like a man writing a fable, he arrives at the moral of his story, which he points out is “the same lesson they teach in Sunday school.” Which is what I love about Gladwell. He stumbles onto some new phenomenon, and he’s trying his damnedest, for page after page, to think through what it means. And part of his mission is sharing the sheer pleasure in thinking it through. This is a special kind of pleasure, and another thing we don’t usually talk about when we talk about what makes a piece of journalism great. It’s the pleasure of discovery, the pleasure of trying to make sense of the world. Take this joyful passage from Jack Hitt’s story about a personal-injury lawsuit so big that the four thousand plaintiff s—just to keep their claims straight—actually had to write their own constitution. As Hitt notes, it’s nearly as long as the U.S. Constitution.

What first drew my attention was that absurd name. Stringfellow. Acid. Pits. Modern life rarely shunts nouns together with such Dickensian economy. After I first encountered that singular name in a newspaper article some four or five years ago, it began to appear in my life eerily, serendipitously. If I was in Washington, the Post had a short update; if in San Francisco, then the Chronicle. If, while dressing in a hotel, I caught an environmental lawyer on C-SPAN, then Stringfellow would be cited offhandedly and without explanation. One evening, seated at an intimate dinner party in New Haven, Connecticut, I casually mentioned my growing interest in String-fellow. Across the table a head turned and said, “I’ve worked on that case.” Then another guest spoke up. He, too, was indirectly involved. I was not following the case; it was pursuing me.

The newspaper reports I read created a sense of Cyclopean dimension: a specially constructed courtroom, private judges, secret negotiations, a quarter-million pages of pretrial documents, and legal processes of absurd intricacy. The case presented a problem unique in the history of American law. How does a court try four thousand cases that are generally similar but legally different? Judge Erik Kaiser came up with an innovative solution: he would bundle the four thousand plaintiffs into groups of roughly seventeen, and try the bundled cases consecutively. Consider the math: 4,000 divided by 17=235 trials. If each one lasted a little under a year—a conservative estimate—the entire process would be wrapped up in two centuries.

Two-thirds of the way into his story, it takes a remarkable turn, one I’ve rarely seen in any piece of reporting. There’s no way for me to explain this turn without actually revealing the spoiler so jump down to the next paragraph right now if you don’t want to know. Ready? Jack Hitt discovers that the premise of his story is completely wrong. Fantastic, right? Or here’s an excerpt from Bill Buford’s hilarious and disturbing book Among the Thugs, where he spends months with soccer hooligans in England.

The thing about reporting is that it is meant to be objective. It is meant to record and relay the truth of things, as if truth were out there, hanging around, waiting for the reporter to show up. Such is the premise of objective journalism. What this premise excludes, as any student of modern literature will tell you, is that slippery relative fact of the person doing the reporting, the modern notion that there is no such thing as the perceived without someone to do the perceiving, and that to exclude the circumstances surrounding the story is to tell an untruth. . . .

I do not want to tell an untruth and feel compelled, therefore, to note that at this moment, the reporter was aware that the circumstances surrounding his story had become intrusive and significant and that, if unacknowledged, his account of the events that follow would be grossly incomplete. And his circumstances were these: the reporter was very, very drunk.

That’s the will to entertain.

Part of what’s exciting about Among the Thugs is that Buford is so honest about what happens between him and his interviewees, especially the awkwardness he feels as an outsider in the midst of this tribe of drunk, violent men. They hate him, and they don’t trust him, and he doesn’t pretend otherwise. There’s a transparency to the reporting. Most of the book is Buford putting himself into one situation after another, and simply describing all the chance encounters he has along the way. It’s an inspiring book to read if you want to try your hand at reporting, because it makes the job seem so damned straightforward, and I can’t count the number of copies I’ve given away over the years to beginning journalists. Buford makes it clear how much of reporting is simply wandering from one place to another, talking to people and writing down what they say and trying to think of something, anything, that’ll shed some light on what’s happening in front of your face.

This explicitness about the process of reporting is true for many of the writers in this collection. It’s a shame this technique is forbidden to most daily newspaper reporters and broadcast journalists, because a lot of the power of these stories comes from the writers telling you step by step what they’re feeling and thinking, as they do their reporting. For example, here’s how Michael Lewis explains his interest in the story of a fifteen-year-old named Jonathan Lebed—a minor who got into trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission for trading stocks online: “When I first read the newspaper reports last fall, I didn’t understand them. It wasn’t just that I didn’t understand what the kid had done wrong; I didn’t understand what he had done.”

Much later in the story Lewis interviews the Chairman of the SEC about Lebed’s supposed crime, and he does something I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a reporter do in an interview with a government official. Lewis tells us what he’s thinking, moment by moment, as the SEC Chair trots out one unconvincing argument after another. It’s breathtaking, and skewers the guy in a way I’ve never seen before or since in an American newspaper. What’s even more breathtaking is that somehow, Lewis doesn’t come across as unfair. He doesn’t seem like a hothead, or someone with an agenda. He comes off as a curious, reasonable guy, the most reasonable guy in the room in fact, a guy who’s both annoyed and amused at the hokum being peddled. It’s done so deftly you don’t even realize how delicate it is, what he’s pulling off. Especially when you consider the big policy questions he’s juggling at the same time. In the middle of telling this great yarn, he’s actually explaining an entirely original way to look at the regulation of the stock market and online trading, an analysis he invented himself over the course of his reporting. And he’s made his explanation simple enough that people like you and me who may know absolutely nothing about the markets will understand what he’s talking about and why it matters at all.

Which brings me to my next point. What I’m about to say doesn’t apply to breaking news stories, which have their own rules and logic, but does apply to stories like the ones in this book, or on the radio show I host. When you’re writing stories like these, I think you’ve really only got two basic building blocks. You’ve got the plot of the story, and you’ve got the ideas the story is driving at. Usually the plot is the easy part. You do whatever research you can, you talk to lots of people, and you figure out what happened. It’s the ideas that kill you. What’s the story mean? What bigger truth about all of us does it point to? You can knock your head against a wall for days thinking that through.

The writers in this book are geniuses when it comes to the ideas. In fact usually their stories would have trouble existing at all, without the scaffolding of ideas they’ve erected to hold the thing up. And some of the moves they pull to deploy their ideas! There’s a section in Lawrence Weschler’s story “Shapinsky’s Karma” where every character in the story walks up to Weschler to tell him the meaning of the story he’s writing about Shapinksy. Some of them even offer titles for his story. Susan Orlean’s “The American Man, Age Ten” is a tour de force on this score, as she tries to think through what it means to be ten. She’s profiling a random suburban kid named Colin Duffy. I could almost pick any three sentences from the story at random and they’ll make my point, but this passage just kills me:

The girls in Colin’s class are named Cortnerd, Terror, Spacey, Lizard, Maggot, and Diarrhea. “They do have other names, but that’s what we call them,” Colin told me. “The girls aren’t very popular.”

“They are about as popular as a piece of dirt,” Japeth [Colin’s friend] said. “Or you know that couch in the classroom? That couch is more popular than any girl. A thousand times more.”

That is a very efficient way to explain a ten-year-old boy’s attitude toward girls. I love the overall tone she invents to write this story. It’s a voice that’s halfway between hers and his.

If Colin Duffy and I were to get married, we would have matching superhero notebooks. . . . We would eat pizza and candy for all of our meals. We wouldn’t have sex, but we would have crushes on each other and, magically, babies would appear in our home. We would win the lottery and then buy land in Wyoming, where we would have one of every kind of cute animal. All the while, Colin would be working in law enforcement—probably the FBI. Our favorite movie star, Morgan Freeman, would visit us occasionally. We would listen to the same Eurythmics song (“Here Comes the Rain Again”) over and over again and watch two hours of television every Friday night. We would both be good at football, have best friends, and know how to drive; we would cure AIDS and the garbage problem and everything that hurts animals. We would hang out a lot with Colin’s dad. For fun, we would load a slingshot with dog food and shoot it at my butt. We would have a very good life.

Much later in the story, Orlean states more explicitly some of her conclusions about Colin’s view of the world.

The collision in his mind of what he understands, what he hears, what he figures out, what popular culture pours into him, what he knows, what he pretends to know, and what he imagines makes an interesting mess. The mess oft en has the form of what he will probably think like when he is a grown man, but the content of what he is like as a little boy.

One thing I love about Weschler and Orlean (and, come to think of it, most of these writers) is their attitude toward the people they’re writing about. Weschler is clearly skeptical of his protagonist, Akumal. Orlean is not in agreement with her ten-year-old. But they try to get inside their protagonists’ heads with a degree of empathy that’s unusual. Theirs is a ministry of love, in a way we don’t usually discuss reporters’ feelings toward their subjects. Or at least, they’re willing to see what is lovable in the people they’re interviewing. (Weschler’s an interesting case when it comes to this, because he’s mildly annoyed by his main character for the early part of his story, and then comes to have an obvious and real affection for him.)

David Foster Wallace’s story kind of sneaks up on you in this regard. He’s writing about right-wing talk radio, which is, depending on how you look at it, either very easy or very hard to write about well, since it’s something everyone already has an opinion about. And aft er laying out a series of eye-opening details about how the whole talk industry actually works, at some point Wallace just starts to get very, very interested in the question of what sort of guy would be holding forth with these sorts of opinions on the radio. He then produces a set of unusually frank anecdotes and quotes to answer that question. The unusual honesty, by the way, is explained with this helpful footnote:

The best guess re Mr. Z.’s brutal on-record frankness is that either

(a) the host’s on- and off-air personas really are identical, or (b) he regards speaking to a magazine correspondent as just one more part of his job, which is to express himself in a maximally stimulating way.

Part of what’s most interesting about this story, I think, is Wallace’s attitude toward Mr. Z. When he analyzes what Mr. Z. says on the air, he questions some of the most basic premises of Mr. Z.’s occupation. But it’s all done in a way that’s somehow still sympathetic to the guy.

This empathetic mission gives the writing a warmth, and—not incidentally—it helps Wallace and all these writers get away with saying certain unflattering things about their subjects, because it’s clear the overall project of their writing is not a malicious or demeaning one. I like that. And as a reporter, I understand it. I have this experience when I interview someone, if it’s going well and we’re really talking in a serious way, and they’re telling me these very personal things, I fall in love a little. Man, woman, child, any age, any background, I fall in love a little. They’re sharing so much of themselves. If you have half a heart, how can you not?

Chuck Klosterman even makes Val Kilmer sympathetic. Klosterman is both an essayist and a reporter, and as an essayist, he has this fantastically agile brain. He tears through one idea after another with a speed and fierce confidence that I always find kind of inspiring. Some of the essays in his book Sex, Drugs and Cocoa Puff s I’ve read over and over, like the one explaining how Star Wars and Reality Bites are actually the same movie, and how that movie perfectly captures everything about Generation X, which is Klosterman’s generation. (“There are no myths about Generation X,” he writes. “It’s all true.”) When Klosterman does reporting, the superstructure of ideas and the aggressiveness with which he states those ideas are a big part of what makes the stories stand out. And the ideas are especially important when he writes about celebrities. I think celebrity journalism is one of the toughest assignments you can do, because the super-famous are usually guarded about what they reveal, and because they’ve been interviewed so many times before, what’s left for you to explore? Klosterman’s Val Kilmer story is a good example of someone taking a celebrity interview and creating a context and structure that gives the quotes and moments so much meaning. In general, Klosterman writes with a lot of sympathy for his subjects, while still simultaneously pointing out all sorts of things about them that they might find unflattering.

I wish there were a catchy name for stories like this. For one thing, it would’ve made titling this collection a lot easier. Sometimes people use the phrase “literary nonfiction” for work like this, but I’m a snob when it comes to that phrase. I think it’s for losers. It’s pretentious, for one thing, and it’s a bore. Which is to say, it’s exactly the opposite of the writing it’s trying to describe. Calling a piece of writing “literary nonfiction” is like daring you to read it.

In choosing stories for this book, I haven’t tried to include every great nonfiction writer who’s working right now, or even all my favorites. I ended up rereading dozens of essays and stories I’ve loved, some of them by regular contributors to the radio program, some by people I’ve admired from afar. In the end I returned to my original premise—to select journalism I’ve found myself talking about and recommending over the years. And I decided to stick with stories that are built around original reporting of one sort or another, not essays.

Some of these stories are very well-known; some barely known. There’s a whole class of stories I’ve included because the writers are trying to document such remarkable experiences they’ve had. Dan Savage tells how he got so sick of the homophobic policies of the Republican Party that he decided to join the party himself and became a delegate to their state convention, where he caused various sorts of trouble. Coco Henson Scales describes what happens inside a trendy New York restaurant and—even more interesting—inside her head as the hostess there. In her story, celebrities show up and perform exactly as you’d want them to, but never get to see in print. It is possibly the greatest New York Times “Styles Section” feature that will ever be written.

Jim McManus’s poker story is amazing because the facts shouldn’t lay out the way they do. He enters his first poker tournament—the World Series of Poker—to write about it for Harper’s magazine, and he ends up at the final table, pocketing a quarter-million dollars. This is the poker equivalent of showing up at the Olympics, never having competed on track or field, and taking home the bronze for the 100-meter dash. At one point, McManus squares off against one of his heroes, a guy whose poker manual he’d read and reread to prepare for the tournament, and—if that’s not enough—they end up playing one of the hands the guy wrote about in his book. “I’ve studied the passage so obsessively,” McManus writes, “I believe I can quote it verbatim.” His Harper’s article, by the way, was published two years before the full-blown poker craze hit America, which explains why he’s so patiently explaining rules and customs of the game that are now familiar to most high school students.

While this is the golden age of this kind of reporting and writing, it’s also a golden age for crap journalism. And for some of the most amazing technological advances for stuffing it down your throat. A lot of daily reporting and news “commentary” just reinforces everything we already think about the world. It lacks the sense of discovery, the curiosity, the uncorny, human-size drama that’s part of all these stories. A lot of daily reporting makes the world seem smaller and stupider.

In that environment, these stories are a kind of beacon. By making stories full of empathy and amusement and the sheer pleasure of discovering the world, these writers reassert the fact that we live in a world where joy and empathy and pleasure are all around us, there for the noticing. They make the world seem like an exciting place to live. I come out of them feeling like a better person—more awake and more aware and more appreciative of everything around me. That’s a hard thing for any kind of writing to accomplish. In times when the media can seem so clueless and beside the point, that’s a great comfort in itself.

Descriere

Designed to mesmerize and inspire, this anthology of the best new masters of nonfiction storytelling has been personally chosen and introduced by Glass, the producer and host of the award-winning public radio program, "This American Life."