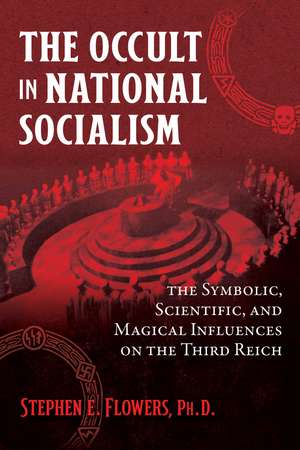

The Occult in National Socialism: The Symbolic, Scientific, and Magical Influences on the Third Reich

Autor Stephen E. Flowers Ph.D.en Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 sep 2022

• Explores the occult influences on various Nazi figures, including Adolf Hitler, Albert Speer, Rudolf Hess, Alfred Rosenberg, and Heinrich Himmler

• Examines the foundations of the movement laid in the 19th century and continuing in the early 20th century

• Explains the rites and runology of National Socialism, the occult dimensions of Nazi science, and how many of the sensationalist descriptions of Nazi “Satanic” practices were initiated by Church propaganda after the war

In this comprehensive examination of Nazi occultism, Stephen E. Flowers, Ph.D., offers a critical history and analysis of the occult and esoteric streams of thought active in the Third Reich and the growth of occult Nazism at work in movements today.

Sharing the culmination of five decades of research into primary and secondary sources, many in the original German, Flowers looks at the symbolic, occult, scientific, and magical traditions that became the foundations from which the Nazi movement would grow. He details the influences of Theosophy, Volkism, and the work of the Brothers Grimm as well as the impact of scientific culture of the time. Looking at the early 20th century, he describes the impact of Guido von List, Lanz von Liebenfels, Rudolf von Sebottendorf, Friedrich Hielscher, and others.

Examining the period after the Nazi Party was established in 1919, and more especially after it took power in 1933, Flowers explores the occult influences on key Nazi figures, including Adolf Hitler, Albert Speer, Rudolf Hess, and Heinrich Himmler. He analyzes Hitler’s usually missed references to magical techniques in Mein Kampf, revealing his adoption of occult methods for creating a large body of supporters and shaping the thoughts of the masses. Flowers also explains the rites and runology of National Socialism, the occult dimensions of Nazi science, and the blossoming of Nazi Christianity. Concluding with a look at the modern mythology of Nazi occultism, Flowers critiques postwar Nazi-related literature and unveils the presence of esoteric Nazi myths in modern occult and political circles.

Preț: 135.72 lei

Preț vechi: 190.79 lei

-29% Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.97€ • 26.60$ • 21.61£

25.97€ • 26.60$ • 21.61£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-12 martie

Livrare express 11-15 februarie pentru 97.26 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781644115749

ISBN-10: 1644115743

Pagini: 544

Ilustrații: 51 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.73 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

ISBN-10: 1644115743

Pagini: 544

Ilustrații: 51 b&w illustrations

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.73 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Inner Traditions

Notă biografică

Stephen Edred Flowers, Ph.D., received his doctorate in Germanic languages and medieval studies from the University of Texas at Austin and studied the history of occultism and runology at the University of Göttingen, Germany. The author of more than 50 books, including Revival of the Runes, he lives near Smithville, Texas.

Extras

INTRODUCTION TO PART I

Historical events of massive proportions have deep and vast root systems. The ideas of National Socialism and its occult dimensions have not only deep roots, but often obscure ones as well. The most common error made by those who represent themselves as doing research into these ideas is that they view the data through a distorted lens shaped by popular slogans. They take their direction from propagandistic phrases such as “Nazism was really a pagan movement,” or “Hitler was a Satanist.” These misdirecting slogans must be put into firm focus and subjected to much more rigorous historical examination.

All of the ideas made manifest in National Socialism have roots in the nineteenth century. The years between 18 and 19 were especially eventful and dynamic for the German-speaking Central European states, most of which would be politically forged together into the Second German Reich by the “Iron Chancellor,” Otto von Bismarck, in 1871. In the broader Western world, the whole century was filled with remarkable ideas and towering figures who vigorously professed them. In the realms of the understanding and implementation of myth and symbol, such figures as Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, J. J. Bachofen, Wilhelm Mannhardt, and Max Müller leap from the pages of history. In the scientific world, men such as Carl Friedrich Gauss, Robert Koch, and Alexander von Humboldt left their indelible marks. The occult world of the nineteenth century offers its own foundational figures, such as Franz Anton Mesmer, Éliphas Lévi, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (née Hahn), and Karl Friedrich Zöllner.

Some of the major ideas that dominated nineteenth-century thought, and which often cooperated or conflicted with one another, were German idealism, biology, evolutionary theories, nationalism, romanticism, social Darwinism, Marxism, and positivism. It is therefore little wonder that the most radical and impetuous children of that century would establish institutions flowing from a heady brew concocted from these ideas.

In order to explain the radical events and historical upheavals of the first half of the twentieth century, we have to understand the effects of intellectual movements beginning a century earlier. Although elite thinkers had held many radically divergent thoughts for a long time in Europe, due to limitations in publishing, education, and economic development this radicalism remained contained. This changed in the nineteenth century. Rational idealism, practiced by Kant and Hegel, was turned into a materialistic economic political philosophy by Karl Marx. Traditional Christian theology was subjected to widespread rationalistic attacks by the new biblical criticism. At the same time, there was an influx of exciting and apparently effective religio-philosophical conceptions from the East. Ideas imported from the Buddhistic and Brahmanic religions, especially as embodied in the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, all led to a new way of thinking that was ready to wipe away the old established philosophies and theologies. One of the most important figures in popularizing the new revolutionary way of thinking was the artist Richard Wagner followed by his former acolyte, Friedrich Nietzsche. This package of ideas was a potent mix for cultural change.

We will observe that a new symbolic culture grew from the seeds of the volkist ideology that were planted and cultivated throughout the course of the nineteenth century. Scientific theories—many of them later discredited, or shown to have been misapplied to cultural issues—grew abundantly throughout the century as well. Occultism as such was an abiding interest of Romantics of the early 18s and over the following decades it became steadily refocused from a center in religious myth into an increasingly “scientific” mode of expression.

In order to see the development of the nineteenth century in a clear context, a short overview of this period in German history is necessary.

GERMAN-SPEAKING CENTRAL EUROPE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Germany had never been a nation-state in the same way France or England had been since the end of the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, there was a nascent collective cultural identity among all German-speaking peoples of Central Europe. These include inhabitants of present-day Germany, Austria, and the northern cantons of Switzerland. Over the course of the nineteenth century, a number of German-speaking political entities—kingdoms, principalities, free cities, and other political corporations in the western part of the German-speaking area—were unified by Bismarck into a state ruled by the Prussian king and now kaiser, Wilhelm I. The century saw Germany go from a collection of independent, almost tribal, kingdoms to a new empire.

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, all of Europe was involved in a cultural debate between Enlightenment thinking couched in Neo-Classical aesthetics and the new approach proposed by the Romantics. Germany was no exception. The Enlightenment valued the rational mind above all else; Enlightenment thinkers questioned received traditions and extolled the virtues of simplicity, precision, and clarity. Enlightenment aesthetics revolved around mechanistic models—the whole world was seen as a great machine or clockwork with the Creator as the great clockmaker. Politically, the Enlightenment favored the development of international institutions and interconnections.

It was in the name of the Enlightenment that Napoleon conquered much of Europe in wars lasting from 1803 to 1815. Romanticism, on the other hand, criticized the arrogant naiveté of the Enlightenment and insisted on the primacy of emotion for human happiness. Romantics turned to the wildness of nature, extolled the “noble savage,” and delved into the night-side of life, into dreams and myths. In the Romantic introversion, the individual body was revalorized as was the collective organic body known as the nation (or Volk). The energy to throw off Napoleon, the foreign conqueror who had originally been welcomed to Germany as a liberator, came from that Romantic spirit.

German Enlightenment thinkers in particular tended to be conservative and optimistic—accepting the political status quo of the fragmented state of the German people. Romantics yearned for a political reality in which the nation and the state would be integrated into an organic whole. Germany, according to Romantic philosophers such as Hegel and Fichte, should be a state made up of German people who speak the German language. This stance was revolutionary and opposed to the conservative position, which favored retaining all of the various political bodies—some two hundred in number.

Romantic revolutionary fervor boiled over in a variety of states in Europe in the year 1848. (Coincidentally, this was the same year that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels issued The Communist Manifesto.) These uprisings were turned back by the conservative forces of many state authorities. This moment also marked the end of those unified cultural movements in which politics, religion, art, and literature could all be seen as exponents of a single philosophical position. After this time, culture began to become fragmented into the compartmentalized aspects of the now familiar modern world. At this point artists, mystics, poets, and writers tended to go underground to pursue their dreams.

Nevertheless, the next generation saw a steady movement toward the unification of various German states under the leadership of Prussia, the most powerful single German state of the time. Wars with Austria (the Seven Weeks’ War of 1866) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) resulted in the consolidation of Prussian power among the western German states. The Franco-Prussian War ended with the victorious Germans occupying Paris and declaring the establishment of the Second German Empire on January 18, 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors in the palace of Versailles.

Austrian cultural history in the last half of the nineteenth century was marked by increasing demands made by ethnic minorities in the Austrian Empire—especially Hungarians and Czechs—upon the central German-speaking authority in Vienna. This pressure helped to promote ideas of a Großdeutschland, a greater unification between the Germanspeaking Austrians and the burgeoning German Reich to the west.

The last quarter of the century witnessed the growth of the German Reich as a world power with the development of advanced technology, overseas colonies, and a modern military.

Additionally, Germany continued to pioneer policies of public welfare, such as health insurance and benefits for disabled and elderly citizens. By the turn of the century, Germany was the most technologically advanced, highly educated, and industrialized country in the world. The expected national ambitions commensurate with these accomplishments in a world that had little room for an upstart major player in geopolitics, could only lead to disaster.

Throughout the nineteenth century the symbolic world of volkism, the realm of scientific research, and the occult subculture were fermenting toward the eventual outpouring of an intoxicating brew in the twentieth century. But it must be remembered that all and everything the twentieth century manifested—the entire spectrum of activity—had roots in what went before it in time. There is nothing “inevitable” or “natural” about how any of these older ideas were used by later artists, scientists, or politicians. Each remains responsible for his own actions. We shall now explore in more detail the foundations of the folkish, scientific, and occult realms of the nineteenth century.

Historical events of massive proportions have deep and vast root systems. The ideas of National Socialism and its occult dimensions have not only deep roots, but often obscure ones as well. The most common error made by those who represent themselves as doing research into these ideas is that they view the data through a distorted lens shaped by popular slogans. They take their direction from propagandistic phrases such as “Nazism was really a pagan movement,” or “Hitler was a Satanist.” These misdirecting slogans must be put into firm focus and subjected to much more rigorous historical examination.

All of the ideas made manifest in National Socialism have roots in the nineteenth century. The years between 18 and 19 were especially eventful and dynamic for the German-speaking Central European states, most of which would be politically forged together into the Second German Reich by the “Iron Chancellor,” Otto von Bismarck, in 1871. In the broader Western world, the whole century was filled with remarkable ideas and towering figures who vigorously professed them. In the realms of the understanding and implementation of myth and symbol, such figures as Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, J. J. Bachofen, Wilhelm Mannhardt, and Max Müller leap from the pages of history. In the scientific world, men such as Carl Friedrich Gauss, Robert Koch, and Alexander von Humboldt left their indelible marks. The occult world of the nineteenth century offers its own foundational figures, such as Franz Anton Mesmer, Éliphas Lévi, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (née Hahn), and Karl Friedrich Zöllner.

Some of the major ideas that dominated nineteenth-century thought, and which often cooperated or conflicted with one another, were German idealism, biology, evolutionary theories, nationalism, romanticism, social Darwinism, Marxism, and positivism. It is therefore little wonder that the most radical and impetuous children of that century would establish institutions flowing from a heady brew concocted from these ideas.

In order to explain the radical events and historical upheavals of the first half of the twentieth century, we have to understand the effects of intellectual movements beginning a century earlier. Although elite thinkers had held many radically divergent thoughts for a long time in Europe, due to limitations in publishing, education, and economic development this radicalism remained contained. This changed in the nineteenth century. Rational idealism, practiced by Kant and Hegel, was turned into a materialistic economic political philosophy by Karl Marx. Traditional Christian theology was subjected to widespread rationalistic attacks by the new biblical criticism. At the same time, there was an influx of exciting and apparently effective religio-philosophical conceptions from the East. Ideas imported from the Buddhistic and Brahmanic religions, especially as embodied in the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, all led to a new way of thinking that was ready to wipe away the old established philosophies and theologies. One of the most important figures in popularizing the new revolutionary way of thinking was the artist Richard Wagner followed by his former acolyte, Friedrich Nietzsche. This package of ideas was a potent mix for cultural change.

We will observe that a new symbolic culture grew from the seeds of the volkist ideology that were planted and cultivated throughout the course of the nineteenth century. Scientific theories—many of them later discredited, or shown to have been misapplied to cultural issues—grew abundantly throughout the century as well. Occultism as such was an abiding interest of Romantics of the early 18s and over the following decades it became steadily refocused from a center in religious myth into an increasingly “scientific” mode of expression.

In order to see the development of the nineteenth century in a clear context, a short overview of this period in German history is necessary.

GERMAN-SPEAKING CENTRAL EUROPE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Germany had never been a nation-state in the same way France or England had been since the end of the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, there was a nascent collective cultural identity among all German-speaking peoples of Central Europe. These include inhabitants of present-day Germany, Austria, and the northern cantons of Switzerland. Over the course of the nineteenth century, a number of German-speaking political entities—kingdoms, principalities, free cities, and other political corporations in the western part of the German-speaking area—were unified by Bismarck into a state ruled by the Prussian king and now kaiser, Wilhelm I. The century saw Germany go from a collection of independent, almost tribal, kingdoms to a new empire.

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, all of Europe was involved in a cultural debate between Enlightenment thinking couched in Neo-Classical aesthetics and the new approach proposed by the Romantics. Germany was no exception. The Enlightenment valued the rational mind above all else; Enlightenment thinkers questioned received traditions and extolled the virtues of simplicity, precision, and clarity. Enlightenment aesthetics revolved around mechanistic models—the whole world was seen as a great machine or clockwork with the Creator as the great clockmaker. Politically, the Enlightenment favored the development of international institutions and interconnections.

It was in the name of the Enlightenment that Napoleon conquered much of Europe in wars lasting from 1803 to 1815. Romanticism, on the other hand, criticized the arrogant naiveté of the Enlightenment and insisted on the primacy of emotion for human happiness. Romantics turned to the wildness of nature, extolled the “noble savage,” and delved into the night-side of life, into dreams and myths. In the Romantic introversion, the individual body was revalorized as was the collective organic body known as the nation (or Volk). The energy to throw off Napoleon, the foreign conqueror who had originally been welcomed to Germany as a liberator, came from that Romantic spirit.

German Enlightenment thinkers in particular tended to be conservative and optimistic—accepting the political status quo of the fragmented state of the German people. Romantics yearned for a political reality in which the nation and the state would be integrated into an organic whole. Germany, according to Romantic philosophers such as Hegel and Fichte, should be a state made up of German people who speak the German language. This stance was revolutionary and opposed to the conservative position, which favored retaining all of the various political bodies—some two hundred in number.

Romantic revolutionary fervor boiled over in a variety of states in Europe in the year 1848. (Coincidentally, this was the same year that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels issued The Communist Manifesto.) These uprisings were turned back by the conservative forces of many state authorities. This moment also marked the end of those unified cultural movements in which politics, religion, art, and literature could all be seen as exponents of a single philosophical position. After this time, culture began to become fragmented into the compartmentalized aspects of the now familiar modern world. At this point artists, mystics, poets, and writers tended to go underground to pursue their dreams.

Nevertheless, the next generation saw a steady movement toward the unification of various German states under the leadership of Prussia, the most powerful single German state of the time. Wars with Austria (the Seven Weeks’ War of 1866) and the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) resulted in the consolidation of Prussian power among the western German states. The Franco-Prussian War ended with the victorious Germans occupying Paris and declaring the establishment of the Second German Empire on January 18, 1871, in the Hall of Mirrors in the palace of Versailles.

Austrian cultural history in the last half of the nineteenth century was marked by increasing demands made by ethnic minorities in the Austrian Empire—especially Hungarians and Czechs—upon the central German-speaking authority in Vienna. This pressure helped to promote ideas of a Großdeutschland, a greater unification between the Germanspeaking Austrians and the burgeoning German Reich to the west.

The last quarter of the century witnessed the growth of the German Reich as a world power with the development of advanced technology, overseas colonies, and a modern military.

Additionally, Germany continued to pioneer policies of public welfare, such as health insurance and benefits for disabled and elderly citizens. By the turn of the century, Germany was the most technologically advanced, highly educated, and industrialized country in the world. The expected national ambitions commensurate with these accomplishments in a world that had little room for an upstart major player in geopolitics, could only lead to disaster.

Throughout the nineteenth century the symbolic world of volkism, the realm of scientific research, and the occult subculture were fermenting toward the eventual outpouring of an intoxicating brew in the twentieth century. But it must be remembered that all and everything the twentieth century manifested—the entire spectrum of activity—had roots in what went before it in time. There is nothing “inevitable” or “natural” about how any of these older ideas were used by later artists, scientists, or politicians. Each remains responsible for his own actions. We shall now explore in more detail the foundations of the folkish, scientific, and occult realms of the nineteenth century.

Cuprins

INTRODUCTION

Essential Questions That Must Be Answered

PART I

Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1800-1900)

Introduction to Part I

1 Foundations of Volkism

The Deep Background of What Became National Socialism

2 Foundations of the Scientific Culture

Science and Pseudoscience of the Nineteenth Century at the Root of National Socialism

3 Foundations of German Occultism

The Deep Occult Background of the Age

PART II

Before Hitler Came

(1900-1919/1933)

Introduction to Part II

4 Symbolic Volkism

The World of Symbols and Signs into which the Third Reich Entered

5 Preludes in Science and Pseudoscience

Science as Symbol and Weapon

6 Occult Culture in Greater Germany

The Fantastic Occulture of the Age

PART III

Myth of the Twentieth Century (1919-1945)

Introduction to Part III

7 Symbolic Elements in the NSDAP

How Signs, Symbols, and Ceremonies Were Wielded to Gain and Maintain Power and Control

8 Rituals of National Socialism

Magic and Manipulation

9 Religious Revolution in the Third Reich

The Rise of New Religions

10 Occult Dimensions of Nazi Sciences

The Weaponization of the Occult

11 Occultism and the Third Reich

The Anti-occult Reich as a Step toward Political Spellcasting

PART IV

The Mythology of Nazi Occultism

Introduction to Part IV

12 The Roots of the Myth of Nazi Occultism in Wartime Propaganda Imaginative Propaganda Lays the Foundation of Postwar Tabloid Scholarship

13 Aftermath: Esoteric Nazism Since 1945

The Generation of a New-Age Mythology A Summary and Final Assessments

APPENDIX A

A Simplified Version of the Organizational Structure of the Ahnenerbe

APPENDIX B

The Word Nazi

A Chronological Annotated Bibliography

References

Index

Essential Questions That Must Be Answered

PART I

Foundations of the Nineteenth Century (1800-1900)

Introduction to Part I

1 Foundations of Volkism

The Deep Background of What Became National Socialism

2 Foundations of the Scientific Culture

Science and Pseudoscience of the Nineteenth Century at the Root of National Socialism

3 Foundations of German Occultism

The Deep Occult Background of the Age

PART II

Before Hitler Came

(1900-1919/1933)

Introduction to Part II

4 Symbolic Volkism

The World of Symbols and Signs into which the Third Reich Entered

5 Preludes in Science and Pseudoscience

Science as Symbol and Weapon

6 Occult Culture in Greater Germany

The Fantastic Occulture of the Age

PART III

Myth of the Twentieth Century (1919-1945)

Introduction to Part III

7 Symbolic Elements in the NSDAP

How Signs, Symbols, and Ceremonies Were Wielded to Gain and Maintain Power and Control

8 Rituals of National Socialism

Magic and Manipulation

9 Religious Revolution in the Third Reich

The Rise of New Religions

10 Occult Dimensions of Nazi Sciences

The Weaponization of the Occult

11 Occultism and the Third Reich

The Anti-occult Reich as a Step toward Political Spellcasting

PART IV

The Mythology of Nazi Occultism

Introduction to Part IV

12 The Roots of the Myth of Nazi Occultism in Wartime Propaganda Imaginative Propaganda Lays the Foundation of Postwar Tabloid Scholarship

13 Aftermath: Esoteric Nazism Since 1945

The Generation of a New-Age Mythology A Summary and Final Assessments

APPENDIX A

A Simplified Version of the Organizational Structure of the Ahnenerbe

APPENDIX B

The Word Nazi

A Chronological Annotated Bibliography

References

Index

Recenzii

“Much ink has been spilled on the topic of occult Nazism, but this book goes wider and deeper than most previous literature on this subject. It aims, as the author writes, ‘to bring the question of Nazi occultism into sharper focus with a more refined lens of understanding.’ One of the great merits of the book is that Flowers examines not only the question of the actual nature and extent of occult elements in the Nazi movement and its antecedents but also the huge amount of myth and hype that has grown up around the subject since the end of the Second World War. A central theme of the book is the power of myths, including those that ‘lead to misery and destruction,’ as in the case of the Third Reich. This searching book sheds new light on a troubled subject.”

“Going way beyond the typical sensationalistic tabloid press approach toward the occult undercurrents of National Socialism, as adopted invariably by most authors on the subject for far too many decades, this book is equally a highly welcome counterweight to Nicholas Goodricke-Clarke’s pioneering scholarly study. Himself a well-acknowledged and established occult practitioner as well as an academic scholar, Stephen Flowers deploys the entire arsenal of his critical tradecraft, both emic and etic (in-depth research, shrewd analysis, informed interpretation, historical contextualization, etc.), to present us with a sweeping detailed overview of the contemporary occult and political scene and its eventual culmination in the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust: a sober--and sobering-- depiction that is certain to set new standards for coming research well into the foreseeable future.”

“Although nothing is ‘easy’ about this book--not its argument, subtleties, or beneath-the-floorboards history--Stephen E. Flowers’s study of Nazism and the occult resounds with vitality and depth; this work must be encountered and reckoned with by anyone who hopes to make a serious consideration of its subject.”

“In The Occult in National Socialism, Stephen Flowers approaches this murky and phantasmal historical grotto with a bright lantern of illumination, an undistorted analytical lens, and a keen, unflinching eye. His exploration dispels propaganda from all sides, including that of the Nazis themselves as well as from the Catholic and Protestant churches; overturns cartloads of dubious claims; and punctures a host of untethered hot-air balloons fueled by vaporous theorizing. But this is more than just a debunker’s manual. Flowers is equally adept at cataloging and elucidating the hidden (or even ‘occult’) influences, shadowy organizations, and mysterious personalities that did exist in the pre-Nazi period and the Third Reich. Likewise groundbreaking is the final part of the book: a methodical survey of the postwar era of mythologizing, in which the smoldering ashes of a defeated criminal aggressor-state became a quaggy garden for the cultivation of bizarre tales and pseudo-history. Overall, this volume is a complex study of competing spiritual and ideological forces in a period when the obscured truth often turns out to be more unsettling than the overblown fictions that replaced it.”

“Stephen Flowers rises to the unenviable task of sorting fact from fiction in one of the most notorious questions of the 20th century: To what extent was the Third Reich influenced by and reliant on occult ideas in its quest for world domination? The further we are removed in time from these earth-shattering events, the more the facts about the Nazis’ supposed occult interests will be lost in neo-mythology; we need someone like Flowers to put this history in its proper context and to give a sober assessment of what actually lay behind the few genuine occult interests at work within the Third Reich. Flowers skillfully examines the influences on the intellectual and spiritual life of Germany in the early 20th century, while avoiding the typical sensationalist narrative that takes every insinuation of sinister influence at face value. The bar is now considerably higher with the publication of this long-awaited expert analysis.”

“Going way beyond the typical sensationalistic tabloid press approach toward the occult undercurrents of National Socialism, as adopted invariably by most authors on the subject for far too many decades, this book is equally a highly welcome counterweight to Nicholas Goodricke-Clarke’s pioneering scholarly study. Himself a well-acknowledged and established occult practitioner as well as an academic scholar, Stephen Flowers deploys the entire arsenal of his critical tradecraft, both emic and etic (in-depth research, shrewd analysis, informed interpretation, historical contextualization, etc.), to present us with a sweeping detailed overview of the contemporary occult and political scene and its eventual culmination in the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust: a sober--and sobering-- depiction that is certain to set new standards for coming research well into the foreseeable future.”

“Although nothing is ‘easy’ about this book--not its argument, subtleties, or beneath-the-floorboards history--Stephen E. Flowers’s study of Nazism and the occult resounds with vitality and depth; this work must be encountered and reckoned with by anyone who hopes to make a serious consideration of its subject.”

“In The Occult in National Socialism, Stephen Flowers approaches this murky and phantasmal historical grotto with a bright lantern of illumination, an undistorted analytical lens, and a keen, unflinching eye. His exploration dispels propaganda from all sides, including that of the Nazis themselves as well as from the Catholic and Protestant churches; overturns cartloads of dubious claims; and punctures a host of untethered hot-air balloons fueled by vaporous theorizing. But this is more than just a debunker’s manual. Flowers is equally adept at cataloging and elucidating the hidden (or even ‘occult’) influences, shadowy organizations, and mysterious personalities that did exist in the pre-Nazi period and the Third Reich. Likewise groundbreaking is the final part of the book: a methodical survey of the postwar era of mythologizing, in which the smoldering ashes of a defeated criminal aggressor-state became a quaggy garden for the cultivation of bizarre tales and pseudo-history. Overall, this volume is a complex study of competing spiritual and ideological forces in a period when the obscured truth often turns out to be more unsettling than the overblown fictions that replaced it.”

“Stephen Flowers rises to the unenviable task of sorting fact from fiction in one of the most notorious questions of the 20th century: To what extent was the Third Reich influenced by and reliant on occult ideas in its quest for world domination? The further we are removed in time from these earth-shattering events, the more the facts about the Nazis’ supposed occult interests will be lost in neo-mythology; we need someone like Flowers to put this history in its proper context and to give a sober assessment of what actually lay behind the few genuine occult interests at work within the Third Reich. Flowers skillfully examines the influences on the intellectual and spiritual life of Germany in the early 20th century, while avoiding the typical sensationalist narrative that takes every insinuation of sinister influence at face value. The bar is now considerably higher with the publication of this long-awaited expert analysis.”

Descriere

Stephen E. Flowers, Ph.D., offers a critical history and analysis of the occult and esoteric streams of thought active in the Third Reich and the new flowerings of occult Nazism at work in movements today.