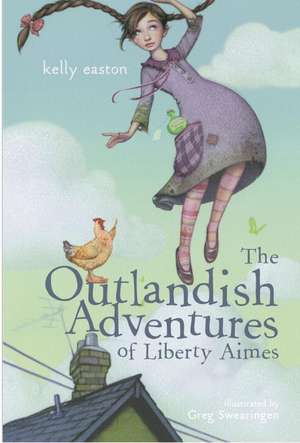

The Outlandish Adventures of Liberty Aimes

Autor Kelly Easton Ilustrat de Greg Swearingenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2011 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

One day, Liberty works up the courage to enter her father's forbidden basement laboratory. There she discovers a world of talking animals and magic potions. With the aid of one such potion, Liberty escapes into the world--and learns that she can talk to animals. She decides her destiny is to find the renowned Sullivan School, where she can live and get an education. Along the way, she meets a wacky cast of characters--some become true friends, but others want to kidnap her.

Preț: 38.39 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 58

Preț estimativ în valută:

7.35€ • 7.58$ • 6.22£

7.35€ • 7.58$ • 6.22£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 11-25 februarie

Livrare express 25-31 ianuarie pentru 16.54 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375837722

ISBN-10: 0375837728

Pagini: 216

Dimensiuni: 130 x 191 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

ISBN-10: 0375837728

Pagini: 216

Dimensiuni: 130 x 191 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Recenzii

Review, Family Fun, September 2009:

"The Outlandish Adventures of Liberty Aimes evokes the work of Roald Dahl and Lewis Carroll."

From the Hardcover edition.

"The Outlandish Adventures of Liberty Aimes evokes the work of Roald Dahl and Lewis Carroll."

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

Kelly Easton is the award-winning author of White Magic and several other young adult novels. She is a teacher and lives in Rhode Island and Martha’s Vineyard with her husband and their children.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Libby Aimes

Once upon a time like now, and in a place like here, there existed a crooked house. The house at 33 Gooch Street was decrepit beyond description. If it could walk, it would limp. If it could talk, it would stutter. If it could smile, it would have rotting teeth. You get the picture.

The back of the house was surrounded by high concrete walls and choked by vines. The front yard had only a picnic bench split in two by lightning, and a row of thorny bushes that never produced a rose.

Insects had fled 33 Gooch, leaving behind their nests' empty catacombs, their webs' dusty strands. Only the mosquitoes came each evening, undiscerning blood_suckers that they are.

People also avoided the house. The postman delivered the mail at a trot. Trick-or-treaters crossed the street, dashing to number 34, the bright yellow house where the man handed out gummy worms.

That man was the only person who knew that inside 33 Gooch lived a family. He knew because he watched the house with great curiosity.

The family was a couple and their only daughter, Liberty, nicknamed Libby, after a brand of canned vegetables.

Libby Aimes was small with two long dark braids and pale skin. She owned only one dress, a gray one, with big pockets to hold her cooking utensils and cleaning supplies.

Although she was ten, she was not in any grade, like you might be. Her parents had never allowed her to go to school. They told the school officials that she would be "homeschooled." Usually, that's a fine thing. For Libby, though, it meant that she was locked up all day, waiting on her parents hand and foot, dodging their insults like a beleaguered catcher.

Some people have names that suit them exactly. Like Lilac, for someone who smells nice. Or Jock, for a boy who's good at sports. Libby's real name, Liberty, was kind of a joke. She was a prisoner in her own house. It was good that her parents always called her by her nickname. She had never heard her real name pass their lips.

Libby's mother, Sal, had grown up at 33 Gooch, but she never talked about that. What she talked about was how, because of Libby, she was now fat, married to a dud, and stuck in her life.

Libby never understood the connection between herself and her mother's extreme tubbiness. Her mother was fat, Libby knew, because she ate nonstop. Each day Sal consumed thirty-two pieces of fried French toast, seven pounds of fried clams, sixteen fried hot dogs, two fried chickens, twenty fried hamburgers, six platters of french fries, three platters of fried noodles, a pie (not fried), six ice cream sundaes, and a variety of other foods. Libby cooked these meals, so she knew the numbers.

The only thing she didn't cook for her mother was the buttergoo pudding Sal consumed three times a day. Libby's father, Mal, cooked it. Mal told Libby that if she dared to taste a drop, he would "teach her a lesson." It was something he often said, although Libby had yet to figure out what the lesson was.

As unpleasant as Sal was, Liberty's father was worse. Mal (which means "evil" in French) was thin as a thread, and so tall that he whacked his head walking through doorways. The constant stooping made him look crooked. Unlike Sal, Mal barely ate a morsel; he said that eating was a sign of bad character.

Mal was the only one who ever left the house. During the day, he sold insurance. "People are terrified of disasters," he said. "I remind them about landslides, tornadoes, hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, fires, termite infestations, carpenter bees, bedbugs, bad guys, and wild goats on rampages. Then I sell them insurance."

Mal was crooked inside as well as outside. If a disaster really did befall one of his customers, Mal had tricks to avoid paying the claims. Libby had heard him numerous times, shouting into the phone he kept in his pocket. "Read the fine print!"

The fine print was writing at the bottom of contracts, so small you could only see it with a magnifying glass. It said that the insurance company was not responsible for any disasters that occurred between the days of Sunday and Saturday.

This made the policy worthless. Oh, Mal was happy when he got to tell some homeless or injured person, "Read the fine print."

Have you ever had a ripe apple fresh from the tree? It is delicious: crunchy and sweet. But once in a while, you bite into an apple that is mushy and vile. Parents are much the same as apples. Most of them are perfectly lovely, but occasionally you find one that is rotten. Mal was such a bad apple. He also smelled rotten, since he bathed only during months that had a Z in them. Baths cost too much, he said, but Libby figured he just liked being filthy and gross to match his personality.

In addition to making Libby do all the cooking and cleaning, Mal made her pry up the bricks on the back patio and then lay them again, even in the winter, to teach her a lesson. She had to wax his shoes, cut his toenails, groom his mustache, and brush his teeth; his breath smelled like a warthog's (at least, that was what she imagined).

"Do you know why you do what I say?" Mal asked Libby ten or twenty times a day.

She was too frightened to answer, but he always answered for her.

"Because I'm a friggin' genius, and you are a zero."

Some people, when told they're a zero, take it to heart and feel like a nothing. But Libby was too smart for that. She knew that a zero was a fine, round thing. Put a zero on any number, she thought, and it becomes more valuable.

Sal also called Mal "the genius." She'd say, "The genius is stinking up the bathroom again." Or, "The genius thinks we can pay the mortgage with ideas." For no matter how many people "the genius" cheated, Libby's family was always dead broke.

Once upon a time like now, and in a place like here, there existed a crooked house. The house at 33 Gooch Street was decrepit beyond description. If it could walk, it would limp. If it could talk, it would stutter. If it could smile, it would have rotting teeth. You get the picture.

The back of the house was surrounded by high concrete walls and choked by vines. The front yard had only a picnic bench split in two by lightning, and a row of thorny bushes that never produced a rose.

Insects had fled 33 Gooch, leaving behind their nests' empty catacombs, their webs' dusty strands. Only the mosquitoes came each evening, undiscerning blood_suckers that they are.

People also avoided the house. The postman delivered the mail at a trot. Trick-or-treaters crossed the street, dashing to number 34, the bright yellow house where the man handed out gummy worms.

That man was the only person who knew that inside 33 Gooch lived a family. He knew because he watched the house with great curiosity.

The family was a couple and their only daughter, Liberty, nicknamed Libby, after a brand of canned vegetables.

Libby Aimes was small with two long dark braids and pale skin. She owned only one dress, a gray one, with big pockets to hold her cooking utensils and cleaning supplies.

Although she was ten, she was not in any grade, like you might be. Her parents had never allowed her to go to school. They told the school officials that she would be "homeschooled." Usually, that's a fine thing. For Libby, though, it meant that she was locked up all day, waiting on her parents hand and foot, dodging their insults like a beleaguered catcher.

Some people have names that suit them exactly. Like Lilac, for someone who smells nice. Or Jock, for a boy who's good at sports. Libby's real name, Liberty, was kind of a joke. She was a prisoner in her own house. It was good that her parents always called her by her nickname. She had never heard her real name pass their lips.

Libby's mother, Sal, had grown up at 33 Gooch, but she never talked about that. What she talked about was how, because of Libby, she was now fat, married to a dud, and stuck in her life.

Libby never understood the connection between herself and her mother's extreme tubbiness. Her mother was fat, Libby knew, because she ate nonstop. Each day Sal consumed thirty-two pieces of fried French toast, seven pounds of fried clams, sixteen fried hot dogs, two fried chickens, twenty fried hamburgers, six platters of french fries, three platters of fried noodles, a pie (not fried), six ice cream sundaes, and a variety of other foods. Libby cooked these meals, so she knew the numbers.

The only thing she didn't cook for her mother was the buttergoo pudding Sal consumed three times a day. Libby's father, Mal, cooked it. Mal told Libby that if she dared to taste a drop, he would "teach her a lesson." It was something he often said, although Libby had yet to figure out what the lesson was.

As unpleasant as Sal was, Liberty's father was worse. Mal (which means "evil" in French) was thin as a thread, and so tall that he whacked his head walking through doorways. The constant stooping made him look crooked. Unlike Sal, Mal barely ate a morsel; he said that eating was a sign of bad character.

Mal was the only one who ever left the house. During the day, he sold insurance. "People are terrified of disasters," he said. "I remind them about landslides, tornadoes, hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, fires, termite infestations, carpenter bees, bedbugs, bad guys, and wild goats on rampages. Then I sell them insurance."

Mal was crooked inside as well as outside. If a disaster really did befall one of his customers, Mal had tricks to avoid paying the claims. Libby had heard him numerous times, shouting into the phone he kept in his pocket. "Read the fine print!"

The fine print was writing at the bottom of contracts, so small you could only see it with a magnifying glass. It said that the insurance company was not responsible for any disasters that occurred between the days of Sunday and Saturday.

This made the policy worthless. Oh, Mal was happy when he got to tell some homeless or injured person, "Read the fine print."

Have you ever had a ripe apple fresh from the tree? It is delicious: crunchy and sweet. But once in a while, you bite into an apple that is mushy and vile. Parents are much the same as apples. Most of them are perfectly lovely, but occasionally you find one that is rotten. Mal was such a bad apple. He also smelled rotten, since he bathed only during months that had a Z in them. Baths cost too much, he said, but Libby figured he just liked being filthy and gross to match his personality.

In addition to making Libby do all the cooking and cleaning, Mal made her pry up the bricks on the back patio and then lay them again, even in the winter, to teach her a lesson. She had to wax his shoes, cut his toenails, groom his mustache, and brush his teeth; his breath smelled like a warthog's (at least, that was what she imagined).

"Do you know why you do what I say?" Mal asked Libby ten or twenty times a day.

She was too frightened to answer, but he always answered for her.

"Because I'm a friggin' genius, and you are a zero."

Some people, when told they're a zero, take it to heart and feel like a nothing. But Libby was too smart for that. She knew that a zero was a fine, round thing. Put a zero on any number, she thought, and it becomes more valuable.

Sal also called Mal "the genius." She'd say, "The genius is stinking up the bathroom again." Or, "The genius thinks we can pay the mortgage with ideas." For no matter how many people "the genius" cheated, Libby's family was always dead broke.