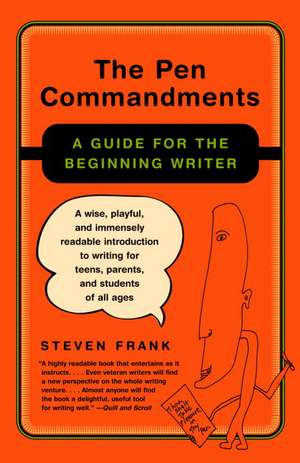

The Pen Commandments: A Guide for the Beginning Writer

Autor Steven Franken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2004

With outrageous anecdotes (how a kid's oral surgery led to the ultimate writing assignment) and irreverent advice (Thou Shalt Not Kill Thy Sentences), Frank shows how to conquer writer's block, make friends with punctuation, and live forever in words. If you want to inspire your kids of just want to brush up on your own skills, The Pen Commandments will change—and enliven—the way you write forever.

Preț: 87.43 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 131

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.73€ • 17.37$ • 13.95£

16.73€ • 17.37$ • 13.95£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400032297

ISBN-10: 1400032296

Pagini: 314

Dimensiuni: 142 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400032296

Pagini: 314

Dimensiuni: 142 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Mr. Frank has been a high school English teacher for ten years. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife and two children.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

One

Thou Shalt Honor Thy Reader

On the first day of school where I teach, the students all line up in the yard according to grade. They mill about, getting reacquainted after a summer apart, and they tell stories. One year I heard someone cry out, "Ewwww, that's disgusting!" I turned and saw a small crowd huddled around a boy named Jason who was describing the oral surgery he had had back in June.

"They found out I had an extra tooth growing down from the roof of my mouth. If we did nothing, it would keep on growing till it touched my tongue. So the dentist said he'd have to pull it."

"Did it hurt?" asked one girl.

"Well, when he cut the hole around the tooth, that wasn't so bad. But then he took a pair of pliers and started twisting it back and forth, like a nail. That I felt."

"Was there a lot of blood?" a boy asked.

"That depends on how you define a lot. Let's just say I couldn't spit fast enough and kept swallowing instead. Finally he got the tooth out, jammed some cotton up there, and told me to hold it in place with my tongue."

"What's it look like now?"

Jason smiled a thin, wicked smile. Then he threw back his head and opened wide for all the kids to gaze at--and be grossed out by--the crater in the roof of his mouth. There was a roar of disgusted cries, and then one kid said, "Can I see that again?"

That's when it hit me: a writing assignment designed to gross us out, to keep us gathered around a composition the way the kids had all gathered around Jason. The topic: "An Accident That Happened." The goal: include so many gory details that at least five of your classmates will either hurl their lunch or skip their dinner. Now you may ask how a writer who incites mass vomiting is respecting his reader, but I invite you to visit my classroom on the day these compositions are read aloud. People love to hear the stories behind scars just as much as they love to tell them.

The Right Topic

The leading cause of writer apathy among today's students is bad topics. "Write about your summer vacation." "Describe your room." "Describe your family." "Write a letter to the editor." "Write a plot summary." "Write a character analysis." "Write a report about the uses of zinc oxide in a developed society." Write a this, write a that, write a write a write a write--why write at all?

If you're not inspired by a writing topic, ask to change it. Ask your teacher if you can describe your family from the dog's point of view, or the fish's. Ask if your plot summary can include blanks so that your classmates can try to guess the title when you read it aloud. Ask if your character analysis can include a literary personals ad to help your character find a date. Don't ask--send your letter to a real editor of a real newspaper. Or better yet, start a newspaper of your own. Sell subscriptions to pay for the Xeroxing costs. Do whatever you can to feel passionate about writing, because if you find the topic boring to write, your reader will find it just as boring to read.

When my brother-in-law Steve was a freshman in college, he had to write an essay entitled "A World Without Books." The professor had the poor judgment to announce the assignment in mid-March, just as the NCAA basketball tournament was getting under way. Steve was too busy placing bets to ponder a world without books, so he ignored the topic until the night before it was due. At eleven p.m., after UCLA had trounced Michigan and won Steve enough money for a weekend in Tahoe, he sat down to his Smith-Corona typewriter and wrote a perfectly suitable topic sentence: "A world without books would be a miserable place in which to live." Within seconds Steve's head fell forward and crashed onto the keys of his typewriter. Three hours later he woke up, squinted at his paper, and saw the topic sentence followed by a row of zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz's.

Two cups of coffee and four No-Doz tablets later, Steve tried again. To warm up his typing fingers, he retyped the topic sentence: "A world without books would be a miserable place in which to live." The third cup of coffee was still steaming when his head lolled forward and thudded to the typewriter. At six o'clock the next morning, there was the same topic sentence, this time followed by a row of pppppppppppppppppppppppp's.

With z's and p's imprinted on his forehead and not much more on the page, and with the essay due in less than three hours, Steve got the sillies. He began to type over and over: "a world without books. a world without books. a world without books..." Near the bottom of the page he accidentally typed something different: a world without books. a world without books. a world without bookies. He stopped and reread that phrase: a world without bookies. "That's it!" he thought. "That's something I can write about."

He loaded a fresh sheet. "A world without bookies would be a miserable place in which to live," he began. And for the next hour and a half Steve wrote a college essay on a topic that thrilled him.

Do you know what his grade was?

A-plus. The professor was blown away by the originality and irreverence of his essay. Not only did he reward him with the highest grade in the class, he thanked him by reading the composition out loud to a lecture hall crammed with five hundred students. "Of the all the essays I read, this was the only one I enjoyed."

Your first reader is often a teacher. Honor thy reader: we're desperate to be entertained.

Show, Don't Tell

Once you've found a topic that keeps you awake, you can honor thy reader by keeping him awake too. While you can't control the flow of caffeine into your reader's blood, you can control the flow of words into his brain. Don't use too many, but be vivid with the ones you choose: show, don't tell.

Early in the school year I ask my students to write an outrageous excuse for why their homework wasn't done. If the excuse is convincing, I let them use it like a get-out-of-jail-free card instead of turning in one assignment during the semester.

One student who did not respect her reader dashed off the cliche, "My dog ate it." "My dog ate it" is as old as a bloodhound who's lost his sense of smell, but even it can be delivered with a little more panache. A more entertaining excuse might have gone, "My homework lay on the floor in slimy, torn pieces. There were teeth marks in the margins and paw prints on my opening paragraph. I followed the trail of slobber into the kitchen, where my dog sat with my conclusion in his mouth." That brief paragraph shows, through storytelling, what the first sentence merely tells, in flat uninteresting fact. It's more fun to read because it hooks you with an image--the slimy, torn pieces on the floor--and then leads you to another image--the dog with a conclusion in his mouth--to explain it. You, the reader, get to complete the puzzle. You aren't passively receiving information; you have to work for it, and the result is a sense of accomplishment and fun. (By the way, the rewritten version is the work of the student who wrote the dog excuse in the first place. With a little help from her classmates, she was able to improve her writing a thousand percent.)

You can always write, "Last night it rained." But isn't it more intriguing to show us that it rained by creating a picture or a sound for the morning after? "I was awakened by the sound of tires splashing through puddles of water. Pulling back the curtain, I saw that the sun had sliced through the clouds and was busy mopping up the streets."

Is this a violation of Pen Commandment 2, Thou Shalt Not Waste Words? It's true I'm using more words to express what could be stated in fewer, but I'm not just adding words to the sentence; I'm adding an image. "Last night it rained" won't stay with the reader nearly as long as the idea of puddles being mopped up by the sun. Less is sometimes less, and more is sometimes more.

Feed Your Reader Well

You can also honor thy reader by not serving him a skimpy meal. Your writing needs to cast a spell on the reader, lure him into a chair and keep him there, engaged, challenged, and well fed. If, for example, you're writing a realtor's brochure for a dream house in the year 2550, it's not enough to describe it as "an awesome home with all the comforts that technology can provide." Your reader wants to know what those comforts are. Will your dream house feature a shower bed that wakes you with a gentle spray of warm water? Will it come with a virtual closet that lets you see how you'll look in an outfit before you put it on? Will it know just the right music to play for your shifting moods?

If you are writing a composition called "______s Make the Best Pets," in which you describe the most outlandish nondomesticated animal you can imagine bringing home, try to write beyond the obvious. Sure, having a pet giraffe would force you to blow the roof off your house and plant many more trees, but how else would it change your life? Would you have to swap your sedan for a convertible? Would you make enemies at the movies every time you and your giraffe sat in the front row? Would you become the first pick on a basketball team if you and your pet were partners? You might even have to buy a skip loader to keep the backyard tidy.

Where do these ideas come from? For some people, right off the top of the head, but for most of us, the only thing that comes off the top of the head is dandruff. Ideas worthy of your reader come from someplace deeper and more satisfying to scratch. Give yourself enough time to reach there.

One effective technique is to brainstorm before you write. A brainstorm is the initial explosion of ideas you might have on a topic:

SAMPLE BRAINSTORM

TOPIC: You are Earth's ambassador to an alien planet. What three things will you take to introduce the human race to the aliens?

You spill ideas onto a page and circle the useful ones. You then draw spokes between main ideas and their offshoots. The main ideas will become topic sentences for paragraphs; the offshoots will become supporting sentences. If I were to expand this brainstorm into an essay, I would plan for three main paragraphs: one on a ball, one on a dictionary, and a third on a McDonald's Happy Meal. My brainstorm has a number of good points I can develop within each paragraph: the ball, a sign of friendship with the aliens, can teach them about the human need for exercise and fun; the dictionary can introduce them to the English language and teach them how to pronounce and spell words; and the McDonald's Happy Meal will help them understand our physiology, our economics, and our taste in food.

On days when compositions are read aloud, I forbid the class to talk while a student reads. As soon as she finishes, however, I want the class to get noisy, either with applause, helpful criticism, or the Hunger Chant. The Hunger Chant permits the students to act like underfed orphans. When a writer hasn't given enough examples, details, or support, I urge everyone to shout, "We want more! We want more! We want more!" The assault usually delivers the message, and the second draft is far more satisfying than the first.

When you finish a piece of writing, listen for the Hunger Chant. The best time to adjust the portions is before you serve the meal.

Avoid Giving Your Reader Whiplash

Have you ever been in a car accident? I certainly hope not, but if you have, you'll know what I mean when I say don't give your reader whiplash.

My first encounter with whiplash occurred on a Friday afternoon twenty years ago. I was driving through the intersection of Pico Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles when a truck ran the red light and smashed into the right side of my car. Just then a second truck traveling in the opposite direction ran the same light and smashed into the left side of my car. I felt like a spinner in a board game, only the players were fighting over who got to spin first.

Since then I've suffered many instances of whiplash, but none of them in a car. The whiplash I've had has been confined to the classroom, where I listen to my students read their compositions:

The most embarrassing moment of my life occurred on my tenth birthday, when my mother dropped my cake. My friends and I were shouting, "We want cake! We want cake!" when all of a sudden my mom comes out of the kitchen carrying a beautiful chocolate cake ablaze with candles. She looks up at us and doesn't see the hot wheel track that we'd set up on the floor. The next thing I knew, my mom tripped over the tracks. The candles blew out on her way down, and she lands with her face in the center of the cake.

Did you notice the abrupt change in tense in the second sentence? Did you feel your mind being jerked back and forth between past and present? Uncomfortable, isn't it? I have often thought of hiring a personal injury attorney to sue my students for the mental whiplash that they cause whenever they change tense like this, but on a teacher's salary I can't even afford the parking at a law firm. Instead, I try to show them that by wavering between past and present, they confuse the reader and break the spell of reading itself. It's better to choose a single tense and be faithful to it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Thou Shalt Honor Thy Reader

On the first day of school where I teach, the students all line up in the yard according to grade. They mill about, getting reacquainted after a summer apart, and they tell stories. One year I heard someone cry out, "Ewwww, that's disgusting!" I turned and saw a small crowd huddled around a boy named Jason who was describing the oral surgery he had had back in June.

"They found out I had an extra tooth growing down from the roof of my mouth. If we did nothing, it would keep on growing till it touched my tongue. So the dentist said he'd have to pull it."

"Did it hurt?" asked one girl.

"Well, when he cut the hole around the tooth, that wasn't so bad. But then he took a pair of pliers and started twisting it back and forth, like a nail. That I felt."

"Was there a lot of blood?" a boy asked.

"That depends on how you define a lot. Let's just say I couldn't spit fast enough and kept swallowing instead. Finally he got the tooth out, jammed some cotton up there, and told me to hold it in place with my tongue."

"What's it look like now?"

Jason smiled a thin, wicked smile. Then he threw back his head and opened wide for all the kids to gaze at--and be grossed out by--the crater in the roof of his mouth. There was a roar of disgusted cries, and then one kid said, "Can I see that again?"

That's when it hit me: a writing assignment designed to gross us out, to keep us gathered around a composition the way the kids had all gathered around Jason. The topic: "An Accident That Happened." The goal: include so many gory details that at least five of your classmates will either hurl their lunch or skip their dinner. Now you may ask how a writer who incites mass vomiting is respecting his reader, but I invite you to visit my classroom on the day these compositions are read aloud. People love to hear the stories behind scars just as much as they love to tell them.

The Right Topic

The leading cause of writer apathy among today's students is bad topics. "Write about your summer vacation." "Describe your room." "Describe your family." "Write a letter to the editor." "Write a plot summary." "Write a character analysis." "Write a report about the uses of zinc oxide in a developed society." Write a this, write a that, write a write a write a write--why write at all?

If you're not inspired by a writing topic, ask to change it. Ask your teacher if you can describe your family from the dog's point of view, or the fish's. Ask if your plot summary can include blanks so that your classmates can try to guess the title when you read it aloud. Ask if your character analysis can include a literary personals ad to help your character find a date. Don't ask--send your letter to a real editor of a real newspaper. Or better yet, start a newspaper of your own. Sell subscriptions to pay for the Xeroxing costs. Do whatever you can to feel passionate about writing, because if you find the topic boring to write, your reader will find it just as boring to read.

When my brother-in-law Steve was a freshman in college, he had to write an essay entitled "A World Without Books." The professor had the poor judgment to announce the assignment in mid-March, just as the NCAA basketball tournament was getting under way. Steve was too busy placing bets to ponder a world without books, so he ignored the topic until the night before it was due. At eleven p.m., after UCLA had trounced Michigan and won Steve enough money for a weekend in Tahoe, he sat down to his Smith-Corona typewriter and wrote a perfectly suitable topic sentence: "A world without books would be a miserable place in which to live." Within seconds Steve's head fell forward and crashed onto the keys of his typewriter. Three hours later he woke up, squinted at his paper, and saw the topic sentence followed by a row of zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz's.

Two cups of coffee and four No-Doz tablets later, Steve tried again. To warm up his typing fingers, he retyped the topic sentence: "A world without books would be a miserable place in which to live." The third cup of coffee was still steaming when his head lolled forward and thudded to the typewriter. At six o'clock the next morning, there was the same topic sentence, this time followed by a row of pppppppppppppppppppppppp's.

With z's and p's imprinted on his forehead and not much more on the page, and with the essay due in less than three hours, Steve got the sillies. He began to type over and over: "a world without books. a world without books. a world without books..." Near the bottom of the page he accidentally typed something different: a world without books. a world without books. a world without bookies. He stopped and reread that phrase: a world without bookies. "That's it!" he thought. "That's something I can write about."

He loaded a fresh sheet. "A world without bookies would be a miserable place in which to live," he began. And for the next hour and a half Steve wrote a college essay on a topic that thrilled him.

Do you know what his grade was?

A-plus. The professor was blown away by the originality and irreverence of his essay. Not only did he reward him with the highest grade in the class, he thanked him by reading the composition out loud to a lecture hall crammed with five hundred students. "Of the all the essays I read, this was the only one I enjoyed."

Your first reader is often a teacher. Honor thy reader: we're desperate to be entertained.

Show, Don't Tell

Once you've found a topic that keeps you awake, you can honor thy reader by keeping him awake too. While you can't control the flow of caffeine into your reader's blood, you can control the flow of words into his brain. Don't use too many, but be vivid with the ones you choose: show, don't tell.

Early in the school year I ask my students to write an outrageous excuse for why their homework wasn't done. If the excuse is convincing, I let them use it like a get-out-of-jail-free card instead of turning in one assignment during the semester.

One student who did not respect her reader dashed off the cliche, "My dog ate it." "My dog ate it" is as old as a bloodhound who's lost his sense of smell, but even it can be delivered with a little more panache. A more entertaining excuse might have gone, "My homework lay on the floor in slimy, torn pieces. There were teeth marks in the margins and paw prints on my opening paragraph. I followed the trail of slobber into the kitchen, where my dog sat with my conclusion in his mouth." That brief paragraph shows, through storytelling, what the first sentence merely tells, in flat uninteresting fact. It's more fun to read because it hooks you with an image--the slimy, torn pieces on the floor--and then leads you to another image--the dog with a conclusion in his mouth--to explain it. You, the reader, get to complete the puzzle. You aren't passively receiving information; you have to work for it, and the result is a sense of accomplishment and fun. (By the way, the rewritten version is the work of the student who wrote the dog excuse in the first place. With a little help from her classmates, she was able to improve her writing a thousand percent.)

You can always write, "Last night it rained." But isn't it more intriguing to show us that it rained by creating a picture or a sound for the morning after? "I was awakened by the sound of tires splashing through puddles of water. Pulling back the curtain, I saw that the sun had sliced through the clouds and was busy mopping up the streets."

Is this a violation of Pen Commandment 2, Thou Shalt Not Waste Words? It's true I'm using more words to express what could be stated in fewer, but I'm not just adding words to the sentence; I'm adding an image. "Last night it rained" won't stay with the reader nearly as long as the idea of puddles being mopped up by the sun. Less is sometimes less, and more is sometimes more.

Feed Your Reader Well

You can also honor thy reader by not serving him a skimpy meal. Your writing needs to cast a spell on the reader, lure him into a chair and keep him there, engaged, challenged, and well fed. If, for example, you're writing a realtor's brochure for a dream house in the year 2550, it's not enough to describe it as "an awesome home with all the comforts that technology can provide." Your reader wants to know what those comforts are. Will your dream house feature a shower bed that wakes you with a gentle spray of warm water? Will it come with a virtual closet that lets you see how you'll look in an outfit before you put it on? Will it know just the right music to play for your shifting moods?

If you are writing a composition called "______s Make the Best Pets," in which you describe the most outlandish nondomesticated animal you can imagine bringing home, try to write beyond the obvious. Sure, having a pet giraffe would force you to blow the roof off your house and plant many more trees, but how else would it change your life? Would you have to swap your sedan for a convertible? Would you make enemies at the movies every time you and your giraffe sat in the front row? Would you become the first pick on a basketball team if you and your pet were partners? You might even have to buy a skip loader to keep the backyard tidy.

Where do these ideas come from? For some people, right off the top of the head, but for most of us, the only thing that comes off the top of the head is dandruff. Ideas worthy of your reader come from someplace deeper and more satisfying to scratch. Give yourself enough time to reach there.

One effective technique is to brainstorm before you write. A brainstorm is the initial explosion of ideas you might have on a topic:

SAMPLE BRAINSTORM

TOPIC: You are Earth's ambassador to an alien planet. What three things will you take to introduce the human race to the aliens?

You spill ideas onto a page and circle the useful ones. You then draw spokes between main ideas and their offshoots. The main ideas will become topic sentences for paragraphs; the offshoots will become supporting sentences. If I were to expand this brainstorm into an essay, I would plan for three main paragraphs: one on a ball, one on a dictionary, and a third on a McDonald's Happy Meal. My brainstorm has a number of good points I can develop within each paragraph: the ball, a sign of friendship with the aliens, can teach them about the human need for exercise and fun; the dictionary can introduce them to the English language and teach them how to pronounce and spell words; and the McDonald's Happy Meal will help them understand our physiology, our economics, and our taste in food.

On days when compositions are read aloud, I forbid the class to talk while a student reads. As soon as she finishes, however, I want the class to get noisy, either with applause, helpful criticism, or the Hunger Chant. The Hunger Chant permits the students to act like underfed orphans. When a writer hasn't given enough examples, details, or support, I urge everyone to shout, "We want more! We want more! We want more!" The assault usually delivers the message, and the second draft is far more satisfying than the first.

When you finish a piece of writing, listen for the Hunger Chant. The best time to adjust the portions is before you serve the meal.

Avoid Giving Your Reader Whiplash

Have you ever been in a car accident? I certainly hope not, but if you have, you'll know what I mean when I say don't give your reader whiplash.

My first encounter with whiplash occurred on a Friday afternoon twenty years ago. I was driving through the intersection of Pico Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles when a truck ran the red light and smashed into the right side of my car. Just then a second truck traveling in the opposite direction ran the same light and smashed into the left side of my car. I felt like a spinner in a board game, only the players were fighting over who got to spin first.

Since then I've suffered many instances of whiplash, but none of them in a car. The whiplash I've had has been confined to the classroom, where I listen to my students read their compositions:

The most embarrassing moment of my life occurred on my tenth birthday, when my mother dropped my cake. My friends and I were shouting, "We want cake! We want cake!" when all of a sudden my mom comes out of the kitchen carrying a beautiful chocolate cake ablaze with candles. She looks up at us and doesn't see the hot wheel track that we'd set up on the floor. The next thing I knew, my mom tripped over the tracks. The candles blew out on her way down, and she lands with her face in the center of the cake.

Did you notice the abrupt change in tense in the second sentence? Did you feel your mind being jerked back and forth between past and present? Uncomfortable, isn't it? I have often thought of hiring a personal injury attorney to sue my students for the mental whiplash that they cause whenever they change tense like this, but on a teacher's salary I can't even afford the parking at a law firm. Instead, I try to show them that by wavering between past and present, they confuse the reader and break the spell of reading itself. It's better to choose a single tense and be faithful to it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"A highly readable book that entertains as it instructs... Even veteran writers will find a new perspective on the whole writing venture... Almost anyone will find the book a delightful, useful tool for writing well."- Quill and Scroll

“Steven Frank is the English teacher you wish you’d had in high school. That’s because he knows that education and humor make terrific team teachers. If thou wishest to become a better—and more joyful—writer, thou shalt follow The Pen Commandments.”

—Richard Lederer, author of A Man of My Words

"Frank's approach is fresh and irreverent... If writers absorb Frank's commandments, they'll reap a worthwhile reward: good writing."- The Advocate

"Helpful... To be read as you write...Frank is generous; he doesn't want anyone to be frightened away from the sport because the don't know the rules."- Los Angeles Times

“Steven Frank is the English teacher you wish you’d had in high school. That’s because he knows that education and humor make terrific team teachers. If thou wishest to become a better—and more joyful—writer, thou shalt follow The Pen Commandments.”

—Richard Lederer, author of A Man of My Words

"Frank's approach is fresh and irreverent... If writers absorb Frank's commandments, they'll reap a worthwhile reward: good writing."- The Advocate

"Helpful... To be read as you write...Frank is generous; he doesn't want anyone to be frightened away from the sport because the don't know the rules."- Los Angeles Times

Descriere

With practical advice and compelling case studies, Frank unfreezes the pens of struggling writers all around him, from his mail carrier to a former student to his own mom, with this witty and accessible book that entertains as it instructs. Young Adult.