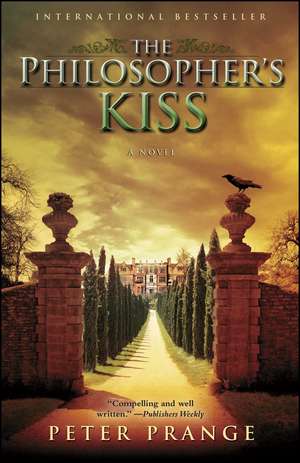

The Philosopher's Kiss: A Novel

Autor Peter Prangeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 apr 2012

Internationally bestselling author Peter Prange makes his US debut with a luminous historical novel.

Truth. Betrayal. Revolution. Love. ENLIGHTENMENT.

PARIS, 1747. Betrayed by God and humanity, eighteen-year-old Sophie moves to the seething French capital and finds work as a serving girl at Café Procope. Here, against her will, she falls deeply in love with Denis Diderot, the famed philosopher and a married man. He and his colleagues are planning the most dangerous book in the world since the Bible: an encyclopedia. Even more scandalous are references concealed within that threaten to undermine both the monarchy and the church. But Sophie soon realizes that even her own rights to freedom, love, and happiness are at risk. Prange powerfully recreates a fascinating era in this spirited story of passion, censorship, self-expression, and rebellion.

Preț: 151.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 227

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.95€ • 30.16$ • 23.97£

28.95€ • 30.16$ • 23.97£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781451617887

ISBN-10: 1451617887

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

ISBN-10: 1451617887

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Notă biografică

Peter Prange is a bestselling German author of fiction and nonfiction. More than 2.5 million copies of his books have sold to date, and he has been published in twenty-four countries. He lives with his wife and daughter in Tübingen, Germany.

Extras

1

“Credo in unum Deum. Patrem omnipotentem, factorem coeli et terrae . . .”

Sophie closed her eyes as she knelt barefoot on the tamped clay floor of her bedroom to pray with all the fervor of her eleven-year-old heart. And this heart of hers was giving her no rest—it was pounding so fiercely, as if it wanted to jump out of her chest. The Apostles’ Creed in Latin was one of the tests that the priest was going to require today of the village children studying for Communion, before they were allowed to approach the Altar of the Lord for the first time in their lives. Although Sophie had already prayed the Credo a dozen times this morning, she said it one more time aloud. The sacrament of Holy Communion, after the sacraments of baptism and confession, was the third door on the long, long journey to the Kingdom of Heaven, and this profession of faith within the Catholic Church was the key to opening this door in her heart.

“. . . visibilium omnium et invisibilium. Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum . . .”

Of course Sophie understood not a word of the prayer, but she knew for certain that the Lord God in Heaven loved her. As she murmured her way through the maze of Latin verses, she felt as if she were running through the boxwood labyrinth that Baron de Laterre had planted in the castle park. She felt utterly lost inside it, without hope, about to reach the end, but if she simply kept rushing along she would manage it somehow. Each verse was a new passageway, the end of each verse a turn in the labyrinth, and suddenly she would be standing free in a sundrenched clearing. As if she had passed through the gates of Heaven into Paradise.

“. . . Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum. Et vitam ventura saeculi. Amen.”

“Don’t you think you’ve practiced enough? It’s time for you to get dressed.”

Sophie opened her eyes. Before her stood her mother, Madeleine. Over her arm she carried a white, billowing cloud—Sophie’s Communion dress.

“I’m so scared,” said Sophie, pulling off her coarse linen shift. “I feel terrible.”

“That’s only because you’ve got nothing in your stomach,” said Madeleine, slipping the dress over Sophie’s naked body. She had sewn it out of a curtain remnant that the baron had given to Sophie. “You haven’t eaten a thing since confession yesterday.”

“What if I’ve forgotten one of my sins?” Sophie hesitated before going on. “Then will I be able to let the Savior into my soul at all? It has to be completely pure.”

“What sort of sins have you committed?” Her mother laughed and shook her head. “No, I think your soul is as shining clean as the sky outside.”

Sophie could feel the curtain material scratching the tips of her breasts, which had been strangely taut for the past few weeks. “People say,” she replied softly, “that I’m a testament to sinful love. Shouldn’t I confess that too?”

“Who said that?” asked Madeleine, and from the vigorous way she was doing up the buttons Sophie could sense that her mother was of an entirely different opinion.

“The priest, Abbé Morel.”

“So, he says that, does he? Even though you relieve him of so much burdensome work? Without you he wouldn’t be able to teach the other children at all.”

“And he also says that Papa is in Hell. Because he never married you. If men and women have children without being married, then they’re no better than cats, Monsieur l’Abbé says.”

“Nonsense,” declared Madeleine, fastening the last button on Sophie’s dress. “The only thing that matters is that parents love each other, like your papa and I. Love is the only thing that counts.”

“Except for reading!” Sophie protested.

“Except for reading.” Madeleine laughed. “And everything else is foolish talk—pay no attention to it.” She kissed Sophie’s forehead and gave her a tender look. “How lovely you are. Here, see for yourself.”

She gave her a little shove, and Sophie stepped in front of the shard of mirror that hung next to the small altar to the Virgin Mary on the whitewashed wall. When she saw herself she had a delightful shock. Looking back at her from the mirror was a girl with red hair falling in thick tresses over a beautiful dress, like the ones that only princesses and fairies wore in the pictures in fairy-tale books.

“If your papa in Heaven can see you now,” said her mother, “he won’t be able to tell you from the angels.”

Could he really see her? Sophie wished so fervently for it to be true that she bit her lip. Her father had died three years before in a foreign land from a violent fever raging in the south of that country. She remembered him so vividly that all she had to do was close her eyes to see him: a big, bearded man with a slouch hat on his head and a pack on his back. He could imitate all the sounds of animals in his bright voice, from horses whinnying to the twittering of strange birds that were found only in Africa. His name was Dorval, and people called him a peddler, but for Sophie he had been a harbinger from another world, a world full of secrets and wonders.

Each year he had come to the church fair in their village, loaded down with knives and shears, pots and pans, notions and brushes—but above all with books. For three weeks, from Ascension Day to Corpus Christi, they would then live together like a real family in their tiny thatched-roof house at the edge of the village. Then Dorval would move on with his treasures. Those three weeks had always been the best time of the year for Sophie. She spent every moment in his company, listening to his stories of faraway places and dangerous adventures, about the fair Melusine or Ogier the Danish giant. With her father she would leaf through the thick, magnificently illustrated books from among the new ones he kept producing out of his pack. Handbooks, herbals, and treatises that apparently had an answer to every question in life: how to cure warts or the hiccups, how to banish the terror of Judgment Day, or how to overcome the evil powers in dreams. From Dorval Sophie had inherited her red hair and the freckles that were sprinkled across her snub nose and cheeks by the thousands, making her green eyes seem to shine even more brightly than her mother’s. Even more important, she had gotten something from Dorval that set her apart from all the other children in the village—an ability that her mother said was worth more than all the treasures in the world: the ability to read and write.

Suddenly something occurred to Sophie, and in an instant her festive mood vanished.

“That man last night,” she said softly.

“What man?” asked her mother, startled.

“The man with the feather in his hat. I heard what he told you.”

“You were eavesdropping on us?” Madeleine had the same expression as Sophie did whenever she was caught doing something forbidden.

“I couldn’t sleep,” Sophie stammered. “Is he going to be—my new papa?”

“No, no, my dear heart, most assuredly not!” Madeleine knelt down and looked her straight in the eye. “How could you believe anything so foolish?”

“Then what did the man want from you? He tried to kiss you!”

“Don’t worry about that. That’s just how men are sometimes.”

“So he’s really not going to be my father?” Sophie asked. Her whole body was trembling because she was so upset.

“Cross my heart! I told him to go to the Devil,” Madeleine said. “But what’s wrong? You look all flustered. I think I’d better give you something to help you relax, or else you’ll feel ill in church.” From the shelf she took one of the many little bottles that stood next to the thick herbal tome, and poured a few drops of a black liquid into a wooden spoon.

“There now, take this,” she said, holding out the spoon. “This will calm you down.”

Sophie hesitated. “Isn’t it a sin? Before Communion?”

“No, no, my heart, it’s not a sin,” said Madeleine as she carefully stuck the spoon into Sophie’s mouth so that not a drop would fall on her white dress. “Medicine is allowed before Communion. You want to pass the test, don’t you?”

© 2003 Droemer Verlag

“Credo in unum Deum. Patrem omnipotentem, factorem coeli et terrae . . .”

Sophie closed her eyes as she knelt barefoot on the tamped clay floor of her bedroom to pray with all the fervor of her eleven-year-old heart. And this heart of hers was giving her no rest—it was pounding so fiercely, as if it wanted to jump out of her chest. The Apostles’ Creed in Latin was one of the tests that the priest was going to require today of the village children studying for Communion, before they were allowed to approach the Altar of the Lord for the first time in their lives. Although Sophie had already prayed the Credo a dozen times this morning, she said it one more time aloud. The sacrament of Holy Communion, after the sacraments of baptism and confession, was the third door on the long, long journey to the Kingdom of Heaven, and this profession of faith within the Catholic Church was the key to opening this door in her heart.

“. . . visibilium omnium et invisibilium. Et in unum Dominum Jesum Christum . . .”

Of course Sophie understood not a word of the prayer, but she knew for certain that the Lord God in Heaven loved her. As she murmured her way through the maze of Latin verses, she felt as if she were running through the boxwood labyrinth that Baron de Laterre had planted in the castle park. She felt utterly lost inside it, without hope, about to reach the end, but if she simply kept rushing along she would manage it somehow. Each verse was a new passageway, the end of each verse a turn in the labyrinth, and suddenly she would be standing free in a sundrenched clearing. As if she had passed through the gates of Heaven into Paradise.

“. . . Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum. Et vitam ventura saeculi. Amen.”

“Don’t you think you’ve practiced enough? It’s time for you to get dressed.”

Sophie opened her eyes. Before her stood her mother, Madeleine. Over her arm she carried a white, billowing cloud—Sophie’s Communion dress.

“I’m so scared,” said Sophie, pulling off her coarse linen shift. “I feel terrible.”

“That’s only because you’ve got nothing in your stomach,” said Madeleine, slipping the dress over Sophie’s naked body. She had sewn it out of a curtain remnant that the baron had given to Sophie. “You haven’t eaten a thing since confession yesterday.”

“What if I’ve forgotten one of my sins?” Sophie hesitated before going on. “Then will I be able to let the Savior into my soul at all? It has to be completely pure.”

“What sort of sins have you committed?” Her mother laughed and shook her head. “No, I think your soul is as shining clean as the sky outside.”

Sophie could feel the curtain material scratching the tips of her breasts, which had been strangely taut for the past few weeks. “People say,” she replied softly, “that I’m a testament to sinful love. Shouldn’t I confess that too?”

“Who said that?” asked Madeleine, and from the vigorous way she was doing up the buttons Sophie could sense that her mother was of an entirely different opinion.

“The priest, Abbé Morel.”

“So, he says that, does he? Even though you relieve him of so much burdensome work? Without you he wouldn’t be able to teach the other children at all.”

“And he also says that Papa is in Hell. Because he never married you. If men and women have children without being married, then they’re no better than cats, Monsieur l’Abbé says.”

“Nonsense,” declared Madeleine, fastening the last button on Sophie’s dress. “The only thing that matters is that parents love each other, like your papa and I. Love is the only thing that counts.”

“Except for reading!” Sophie protested.

“Except for reading.” Madeleine laughed. “And everything else is foolish talk—pay no attention to it.” She kissed Sophie’s forehead and gave her a tender look. “How lovely you are. Here, see for yourself.”

She gave her a little shove, and Sophie stepped in front of the shard of mirror that hung next to the small altar to the Virgin Mary on the whitewashed wall. When she saw herself she had a delightful shock. Looking back at her from the mirror was a girl with red hair falling in thick tresses over a beautiful dress, like the ones that only princesses and fairies wore in the pictures in fairy-tale books.

“If your papa in Heaven can see you now,” said her mother, “he won’t be able to tell you from the angels.”

Could he really see her? Sophie wished so fervently for it to be true that she bit her lip. Her father had died three years before in a foreign land from a violent fever raging in the south of that country. She remembered him so vividly that all she had to do was close her eyes to see him: a big, bearded man with a slouch hat on his head and a pack on his back. He could imitate all the sounds of animals in his bright voice, from horses whinnying to the twittering of strange birds that were found only in Africa. His name was Dorval, and people called him a peddler, but for Sophie he had been a harbinger from another world, a world full of secrets and wonders.

Each year he had come to the church fair in their village, loaded down with knives and shears, pots and pans, notions and brushes—but above all with books. For three weeks, from Ascension Day to Corpus Christi, they would then live together like a real family in their tiny thatched-roof house at the edge of the village. Then Dorval would move on with his treasures. Those three weeks had always been the best time of the year for Sophie. She spent every moment in his company, listening to his stories of faraway places and dangerous adventures, about the fair Melusine or Ogier the Danish giant. With her father she would leaf through the thick, magnificently illustrated books from among the new ones he kept producing out of his pack. Handbooks, herbals, and treatises that apparently had an answer to every question in life: how to cure warts or the hiccups, how to banish the terror of Judgment Day, or how to overcome the evil powers in dreams. From Dorval Sophie had inherited her red hair and the freckles that were sprinkled across her snub nose and cheeks by the thousands, making her green eyes seem to shine even more brightly than her mother’s. Even more important, she had gotten something from Dorval that set her apart from all the other children in the village—an ability that her mother said was worth more than all the treasures in the world: the ability to read and write.

Suddenly something occurred to Sophie, and in an instant her festive mood vanished.

“That man last night,” she said softly.

“What man?” asked her mother, startled.

“The man with the feather in his hat. I heard what he told you.”

“You were eavesdropping on us?” Madeleine had the same expression as Sophie did whenever she was caught doing something forbidden.

“I couldn’t sleep,” Sophie stammered. “Is he going to be—my new papa?”

“No, no, my dear heart, most assuredly not!” Madeleine knelt down and looked her straight in the eye. “How could you believe anything so foolish?”

“Then what did the man want from you? He tried to kiss you!”

“Don’t worry about that. That’s just how men are sometimes.”

“So he’s really not going to be my father?” Sophie asked. Her whole body was trembling because she was so upset.

“Cross my heart! I told him to go to the Devil,” Madeleine said. “But what’s wrong? You look all flustered. I think I’d better give you something to help you relax, or else you’ll feel ill in church.” From the shelf she took one of the many little bottles that stood next to the thick herbal tome, and poured a few drops of a black liquid into a wooden spoon.

“There now, take this,” she said, holding out the spoon. “This will calm you down.”

Sophie hesitated. “Isn’t it a sin? Before Communion?”

“No, no, my heart, it’s not a sin,” said Madeleine as she carefully stuck the spoon into Sophie’s mouth so that not a drop would fall on her white dress. “Medicine is allowed before Communion. You want to pass the test, don’t you?”

© 2003 Droemer Verlag