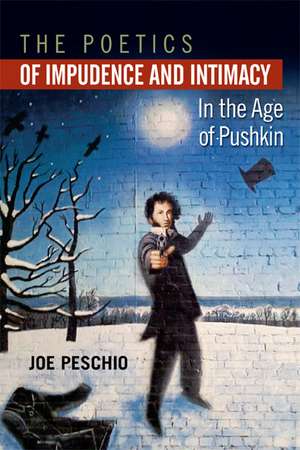

The Poetics of Impudence and Intimacy in the Age of Pushkin: Publications of the Wisconsin Center for Pushkin Studies

Autor Joe Peschioen Limba Engleză Paperback – 12 feb 2013

In early nineteenth-century Russia, members of jocular literary societies gathered to recite works written in the lightest of genres: the friendly verse epistle, the burlesque, the epigram, the comic narrative poem, the prose parody. In a period marked by the Decembrist Uprising and heightened state scrutiny into private life, these activities were hardly considered frivolous; such works and the domestic, insular spaces within which they were created could be seen by the Russian state as rebellious, at times even treasonous.

Joe Peschio offers the first comprehensive history of a set of associated behaviors known in Russian as “shalosti,” a word which at the time could refer to provocative behaviors like practical joking, insubordination, ritual humiliation, or vandalism, among other things, but also to literary manifestations of these behaviors such as the use of obscenities in poems, impenetrably obscure allusions, and all manner of literary inside jokes. One of the period’s most fashionable literary and social poses became this complex of behaviors taken together. Peschio explains the importance of literary shalosti as a form of challenge to the legitimacy of existing literary institutions and sometimes the Russian regime itself. Working with a wide variety of primary texts—from verse epistles to denunciations, etiquette manuals, and previously unknown archival materials—Peschio argues that the formal innovations fueled by such “prankish” types of literary behavior posed a greater threat to the watchful Russian government and the literary institutions it fostered than did ordinary civic verse or overtly polemical prose.

Joe Peschio offers the first comprehensive history of a set of associated behaviors known in Russian as “shalosti,” a word which at the time could refer to provocative behaviors like practical joking, insubordination, ritual humiliation, or vandalism, among other things, but also to literary manifestations of these behaviors such as the use of obscenities in poems, impenetrably obscure allusions, and all manner of literary inside jokes. One of the period’s most fashionable literary and social poses became this complex of behaviors taken together. Peschio explains the importance of literary shalosti as a form of challenge to the legitimacy of existing literary institutions and sometimes the Russian regime itself. Working with a wide variety of primary texts—from verse epistles to denunciations, etiquette manuals, and previously unknown archival materials—Peschio argues that the formal innovations fueled by such “prankish” types of literary behavior posed a greater threat to the watchful Russian government and the literary institutions it fostered than did ordinary civic verse or overtly polemical prose.

Preț: 227.27 lei

Preț vechi: 256.57 lei

-11% Nou

Puncte Express: 341

Preț estimativ în valută:

43.49€ • 45.52$ • 36.20£

43.49€ • 45.52$ • 36.20£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780299290443

ISBN-10: 0299290441

Pagini: 174

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Wisconsin Press

Colecția University of Wisconsin Press

Seria Publications of the Wisconsin Center for Pushkin Studies

ISBN-10: 0299290441

Pagini: 174

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: University of Wisconsin Press

Colecția University of Wisconsin Press

Seria Publications of the Wisconsin Center for Pushkin Studies

Recenzii

“One of the most engaging, yet understudied, aspects of Russia’s ‘golden age’ is the playfulness of its verse, prose, and familiar letters. Peschio brings conceptual power, scholarly rigor, and an appropriately light touch to this important but elusive topic. An absolutely indispensable study of the creative irreverence of the Pushkin period.”—William Todd, Harvard University

“Original, imaginative, well researched, convincingly argued, and excellently written. This book fills an important lacuna in the history of Russian literature and culture of the early nineteenth century.”—Irina Reyfman, author of Ritualized Violence Russian Style: The Duel in Russian Culture and Literature

“This engaging volume by Peschio . . . is a welcome addition to a growing body of books dealing with the icon of Russian literature from an iconoclastic perspective.”—Choice

“Theoretical approaches are handled with deftness and grace. . . . Peschio is also an exemplary archival scholar, scrupulous in his thoroughness and imaginative in the connections he is able to make among seemingly disparate discoveries. . . . Should be required reading for anyone with a serious interest in the literature, society, and culture of early nineteenth-century Russia.”—Slavic and East European Journal

“A model of exacting scholarship—often written, appropriately, with a witty tongue in cheek.”—Slavic Review

Notă biografică

Joe Peschio is associate professor of Russian and coordinator of the Slavic languages program at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.

Cuprins

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Roots and Contexts

The Semantics and Etymology of Misbehavior

Contexts: Domesticity, Society, State

The Verse Shalost'

2 Arzamas: Rudeness

Like Talk

Rudeness and Domesticity in the Arzamasian Letter

3 The Green Lamp: Banter

Arkadii Rodzianko's "Ligurinus"

Del'vig's "Fanni" and Del'vig's "Shack"

4 Ruslan and Liudmila: Rudeness and Banter

Sexual Banter and Eroticism in Ruslan and Liudmila

"Blush You Wretch!": Rudeness in Ruslan and Liudmila and Its Impact on Youth Culture

Epilogue: Pushkin the Pornographer Two Hundred Years Later

Notes

Index

Descriere

In early nineteenth-century Russia, members of jocular literary societies gathered to recite works written in the lightest of genres: the friendly verse epistle, the burlesque, the epigram, the comic narrative poem, the prose parody. In a period marked by the Decembrist Uprising and heightened state scrutiny into private life, these activities were hardly considered frivolous; such works and the domestic, insular spaces within which they were created could be seen by the Russian state as rebellious, at times even treasonous.

Joe Peschio offers the first comprehensive history of a set of associated behaviors known in Russian as “shalosti,” a word which at the time could refer to provocative behaviors like practical joking, insubordination, ritual humiliation, or vandalism, among other things, but also to literary manifestations of these behaviors such as the use of obscenities in poems, impenetrably obscure allusions, and all manner of literary inside jokes. One of the period’s most fashionable literary and social poses became this complex of behaviors taken together. Peschio explains the importance of literary shalosti as a form of challenge to the legitimacy of existing literary institutions and sometimes the Russian regime itself. Working with a wide variety of primary texts—from verse epistles to denunciations, etiquette manuals, and previously unknown archival materials—Peschio argues that the formal innovations fueled by such “prankish” types of literary behavior posed a greater threat to the watchful Russian government and the literary institutions it fostered than did ordinary civic verse or overtly polemical prose.

Joe Peschio offers the first comprehensive history of a set of associated behaviors known in Russian as “shalosti,” a word which at the time could refer to provocative behaviors like practical joking, insubordination, ritual humiliation, or vandalism, among other things, but also to literary manifestations of these behaviors such as the use of obscenities in poems, impenetrably obscure allusions, and all manner of literary inside jokes. One of the period’s most fashionable literary and social poses became this complex of behaviors taken together. Peschio explains the importance of literary shalosti as a form of challenge to the legitimacy of existing literary institutions and sometimes the Russian regime itself. Working with a wide variety of primary texts—from verse epistles to denunciations, etiquette manuals, and previously unknown archival materials—Peschio argues that the formal innovations fueled by such “prankish” types of literary behavior posed a greater threat to the watchful Russian government and the literary institutions it fostered than did ordinary civic verse or overtly polemical prose.