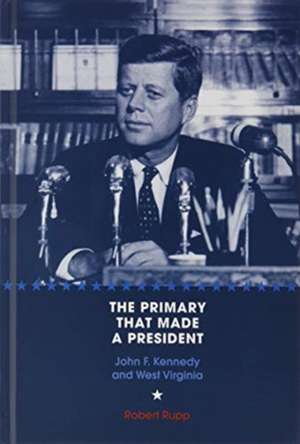

The Primary That Made a President: John F. Kennedy and West Virginia

Autor Prof. Robert O. Rupp Ph.D.en Limba Engleză Hardback – 21 aug 2020

Besides propelling Kennedy to the Democratic nomination, the West Virginia primary changed the face of politics by advancing religious tolerance, foreshadowing future political campaigns, influencing public policy, and drawing national attention to a misunderstood region. It meant the end of a taboo that kept the Catholic faith out of American politics; the rise of the primary as a political tool for garnering delegate support; the beginning of a nationwide confrontation with Appalachian stereotypes; and the seeds for what would become Kennedy’s War on Poverty. Rupp explores these themes and more to discuss how a small Appalachian state, overwhelmingly poor and Protestant, became a key player in the political future of John F. Kennedy.

The first of its kind among Kennedy biographies or histories of the 1960 election, this book offers a sustained scholarly analysis of the 1960 West Virginia presidential primary and its far-reaching significance for the political climate in the US.

Preț: 332.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 499

Preț estimativ în valută:

63.67€ • 65.78$ • 52.99£

63.67€ • 65.78$ • 52.99£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781621905738

ISBN-10: 162190573X

Pagini: 234

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: University of Tennessee Press

Colecția Univ Tennessee Press

ISBN-10: 162190573X

Pagini: 234

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.54 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: University of Tennessee Press

Colecția Univ Tennessee Press

Notă biografică

ROBERT O. RUPP is a professor of history and political science at West Virginia Wesleyan College. For more than a decade, he has authored a weekly op-ed column for the Charleston Gazette on all facets of West Virginia history and politics, and he serves as the election analyst for West Virginia Public Radio. He is past chair of the West Virginia State Election Commission.

Extras

The 1960 West Virginia presidential primary is arguably the most storied contest in modern American politics. And yet, John F. Kennedy traveled so quickly from being a dynamic presidential candidate to a martyred president that many forget his debt to West Virginia in his quest for the Democratic presidential nomination. Kennedy himself acknowledged this debt when he returned, as president, to the state to celebrate its centennial on June 20, 1963. At that event, he declared, “I would not be where I am, I would not have some of the responsibilities which I now bear, if it had not been for the people of West Virginia.” Besides propelling Kennedy to the Democratic nomination, the West Virginia primary changed the face of politics by advancing religious tolerance, foreshadowing future political campaigns, influencing public policy, and perpetuating regional stereotypes. This book will examine these four themes as well as other aspects of this important political contest in the Mountain State 60 years ago.

When the president spoke at the centennial celebration in Charleston that day, he didn’t mention the difficulties his campaign faced during the nearly five weeks spent campaigning across West Virginia, the most prominent of which was his Catholicism. In those weeks, the press and the candidate turned the primary into a referendum on religious tolerance.

The religious issue became an important factor in the West Virginia contest after the Wisconsin presidential primary on April 10, 1960. Prior to that, Kennedy and his advisors viewed the West Virginia primary as an easy contest that would serve as an insurance policy if opponent Hubert Humphrey remained in the fight after Wisconsin. In fact, a December statewide poll of Democratic voters by Lou Harris showed Kennedy beating Humphrey in West Virginia 70 to 30 percent.

But everything changed after that Wisconsin primary. While Kennedy handily beat Humphrey with 476,024 votes to 366,753, the press credited his victory to a strong turnout of Catholic voters, who composed 30 percent of Wisconsin’s population. And a new post-Wisconsin Lou Harris poll of selected precincts showed Kennedy trailing Humphrey 60 to 40 percent, with the explanation that before the Wisconsin primary, West Virginia voters didn’t know Kennedy was a Catholic. Now they did.

As a result, the primary caught the attention of the nation and beyond as a test case for religious bigotry. As Parkersburg newspaper editor James Young summed it up, “West Virginians will either bury their prejudice, or they will bury John Kennedy.” A Kennedy victory in a state where Catholics made up only 4 percent of the population would demonstrate that a Catholic could get Protestant votes. But a defeat would be attributed to one factor: prejudice.

On election night, Ken Kurtz of WSAZ television in Charleston explained that the election hinged on “how [Kennedy’s] Roman Catholic religion will sit at the polls with West Virginia’s heavily Protestant voters,” with Kennedy steadfastly denying that his religion “should have or has had much influence on the election.”

West Virginia voters agreed with the candidate: Kennedy won in a landslide, carrying 50 of the 55 counties and collecting almost 61 percent of the popular vote. The Charleston Gazette described the results as a “devastating victory” that should prompt reconsideration by those party professionals who held Kennedy “at arm’s length because of doubts that a Roman Catholic could be elected to the White House.”

As president, Kennedy reminisced about the West Virginia primary with his friend Ken O’Donnell one evening at the White House: “Just think, if I had buried Hubert in Wisconsin, we would not be sitting here now." His statement led O’Donnell to claim that this one primary election allowed Kennedy to “lick the religious issue in a showdown test that certainly must be a monument in American political history.”

The second impact of the West Virginia contest was how the primary provided a preview of future political campaigns. Not only were presidential candidates chosen in popular elections instead of party back rooms, but they also needed more money to run a campaign, and they needed to spend that money in a particular way to appeal to voters. The Kennedy campaign in the Mountain State prefigured modern presidential campaigns in expenditures as well as its allocation to television and the mounting of an impressive, statewide organization. Ralph McGill of the Atlanta Constitution called Kennedy’s victory a “dramatic example of what thorough, if expensive, organization can produce if handled by professionals.”

Joe Kennedy famously said they were going to sell his son “like soap flakes.” To accomplish that promotion in West Virginia, the Kennedy campaign previewed what McGill called the “latest scientific mechanisms” in its use of television, polling, and computers. The campaign focused on creating an image of a candidate that Joe championed as the first popular-culture political celebrity, boasting that John’s picture on a magazine cover boosted sales.

The distance between Boston, Massachusetts, and Charleston, West Virginia, may have been 800 miles, but the distance between John F. Kennedy and West Virginia seemed far more when he started his campaign in the Mountain State. This was most apparent when his life experience stood in stark contrast to that of his primary opponent, Hubert Humphrey. While the Minnesota senator had witnessed up-close poverty, the Massachusetts senator had little exposure to it until he started campaigning in West Virginia.

Kennedy’s experience in West Virginia became a teachable moment for the future president, one that influenced the policies of his administration and the direction for the nation, especially regarding federal attention on Appalachia. The candidate’s exposure to poverty provided motivation for a food stamp proposal and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), and it helped plant the seeds for a future War on Poverty. Several of those programs, like the food stamp program, survive today.

Kennedy was personally affected by the poverty, poor nutrition, joblessness, and hopelessness he saw firsthand in West Virginia. He spent time passing abandoned miners’ homes, with boards over windows called Eisenhower curtains, and considered it his “education.” Ramie Barker, who would become a senior advisor to West Virginia governor Earl Ray Tomblin, says, “Traveling around here changed him. He learned to become a president.” Barker notes that he “saw wives line up for surplus government food, and he heard about kids who saved their school milk for younger siblings at home.”

During the last week of the campaign Kennedy emphasized “he was glad that he entered the West Virginia primary because it gave him an opportunity to see the plight of men who have lost work because of automation.” Referring to the primary, he said that “This is the best school, the hardest school, and in many ways the most somber school of learning about this problem.”

As Richard Godwin wrote “Kennedy was in West Virginia to win an election. But in that struggle he was learning more about America; about that underside of American life that he had never experienced so personally, intimately.” Goodwin related that midway in the West Virginia primary campaign, Kennedy came to the Washington office and commenting to no one in particular said: “You can’t imagine how those people live down there. I was better off in the war than they are in those coal mines. It’s not right. I’m going to do something about it. If we make it.” Then he added ironically: “Even if they are a bunch of bigots.”

In his televised debate, Kennedy emphasized how his almost five weeks in the Mountain State would impact his presidency by saying “A President can hear about those problems (in West Virginia)—he can read reports—but unless he has spent a month here, seeing it for himself and talking with people, he cannot fully grasp this state’s urgent need for action.” But this recognition of the state and promise of action for the state had an important geographic component as the candidate went on to state that “For America is not just Chicago and Los Angeles—it is Logan and Beckley and Welch as well. The candidate often reminded his audiences that he had been in the state so long, that he learned the geography of the Mountain State. He knew the difference between Charleston and Charles Town; had been the only presidential candidate to have come to Welch three times, or visited Collins High School twice and knew “where Slab Fork is and has been there.” Never before had a presidential contender spent so much time in a state, and it could be argued that never before or since had a future president learned so much.

The experience motivated Kennedy to back up the promises he made to West Virginians during the campaign with concrete public policy programs based on governmental help. Key to these programs was the philosophy that these once proud and able people weren’t poor and malnourished because they deserved it, but because of circumstances beyond their control.

In regard to policy, the contest brought national attention to the economic problems in Appalachia and kindled Kennedy’s interest in fighting rural poverty, which ultimately lead to the creation of a number of initiatives and programs by Lyndon Johnson. But such attention and subsequent action came at a price. The so-called “rediscovery” of white poverty in the upland South brought with it increased attention to stereotypes. Appalachia in general and West Virginia in particular were portrayed negatively in popular culture and mainstream media.

The fourth impact of the primary campaign rests both in its challenge to and perpetuation of stereotypes of the state and region. On the upside, the outcome of the primary undermined outsiders’ low expectations of state residents, who confounded conventional wisdom due to the strong Appalachian value of judging people on an individual basis. After the election, a West Virginia newspaper argued, “Sen. Kennedy’s victory proves what some of us have been trying to say all along. That West Virginia is not the hotbed of religious prejudice some of our distinguished visitors have supposed it to be. We have our religious feelings, to be sure, and here and there they run deep and bitter, but in a purely political campaign, they are not decisive.”

The downside, however, was reflected in reports of West Virginia as an impoverished state, with photographs often showing hard times on gaunt faces. Appalachia had always been victim of such caricatures, but it was made worse in the spring of 1960 by the invasion of the national press with negative coverage that exaggerated the role of religious bigotry while resorting to stereotypes of the region. Charleston reporter L. T. Anderson pointed out “West Virginia was badly portrayed to the nation. It was pictured as a kingdom of defiant, vulgar, gross and stupid bigotry.”

When the Massachusetts senator began his nomination effort, Ben Bradlee of Newsweek asked him at the end of 1959 if he thought he could win. Kennedy answered, “Yes, if I don’t make a single mistake myself and if I don’t get maneuvered into a position where there is no way out.” In other words, he could never finish second in any primary, or get into a situation like Harold Stassen did in 1948, where everything was riding on one event (the Oregon primary) and he blew it. After the Wisconsin primary, the West Virginia contest unexpectedly became that one event that could derail Kennedy’s quest. It became an election that the candidate had to win.

When the president spoke at the centennial celebration in Charleston that day, he didn’t mention the difficulties his campaign faced during the nearly five weeks spent campaigning across West Virginia, the most prominent of which was his Catholicism. In those weeks, the press and the candidate turned the primary into a referendum on religious tolerance.

The religious issue became an important factor in the West Virginia contest after the Wisconsin presidential primary on April 10, 1960. Prior to that, Kennedy and his advisors viewed the West Virginia primary as an easy contest that would serve as an insurance policy if opponent Hubert Humphrey remained in the fight after Wisconsin. In fact, a December statewide poll of Democratic voters by Lou Harris showed Kennedy beating Humphrey in West Virginia 70 to 30 percent.

But everything changed after that Wisconsin primary. While Kennedy handily beat Humphrey with 476,024 votes to 366,753, the press credited his victory to a strong turnout of Catholic voters, who composed 30 percent of Wisconsin’s population. And a new post-Wisconsin Lou Harris poll of selected precincts showed Kennedy trailing Humphrey 60 to 40 percent, with the explanation that before the Wisconsin primary, West Virginia voters didn’t know Kennedy was a Catholic. Now they did.

As a result, the primary caught the attention of the nation and beyond as a test case for religious bigotry. As Parkersburg newspaper editor James Young summed it up, “West Virginians will either bury their prejudice, or they will bury John Kennedy.” A Kennedy victory in a state where Catholics made up only 4 percent of the population would demonstrate that a Catholic could get Protestant votes. But a defeat would be attributed to one factor: prejudice.

On election night, Ken Kurtz of WSAZ television in Charleston explained that the election hinged on “how [Kennedy’s] Roman Catholic religion will sit at the polls with West Virginia’s heavily Protestant voters,” with Kennedy steadfastly denying that his religion “should have or has had much influence on the election.”

West Virginia voters agreed with the candidate: Kennedy won in a landslide, carrying 50 of the 55 counties and collecting almost 61 percent of the popular vote. The Charleston Gazette described the results as a “devastating victory” that should prompt reconsideration by those party professionals who held Kennedy “at arm’s length because of doubts that a Roman Catholic could be elected to the White House.”

As president, Kennedy reminisced about the West Virginia primary with his friend Ken O’Donnell one evening at the White House: “Just think, if I had buried Hubert in Wisconsin, we would not be sitting here now." His statement led O’Donnell to claim that this one primary election allowed Kennedy to “lick the religious issue in a showdown test that certainly must be a monument in American political history.”

The second impact of the West Virginia contest was how the primary provided a preview of future political campaigns. Not only were presidential candidates chosen in popular elections instead of party back rooms, but they also needed more money to run a campaign, and they needed to spend that money in a particular way to appeal to voters. The Kennedy campaign in the Mountain State prefigured modern presidential campaigns in expenditures as well as its allocation to television and the mounting of an impressive, statewide organization. Ralph McGill of the Atlanta Constitution called Kennedy’s victory a “dramatic example of what thorough, if expensive, organization can produce if handled by professionals.”

Joe Kennedy famously said they were going to sell his son “like soap flakes.” To accomplish that promotion in West Virginia, the Kennedy campaign previewed what McGill called the “latest scientific mechanisms” in its use of television, polling, and computers. The campaign focused on creating an image of a candidate that Joe championed as the first popular-culture political celebrity, boasting that John’s picture on a magazine cover boosted sales.

The distance between Boston, Massachusetts, and Charleston, West Virginia, may have been 800 miles, but the distance between John F. Kennedy and West Virginia seemed far more when he started his campaign in the Mountain State. This was most apparent when his life experience stood in stark contrast to that of his primary opponent, Hubert Humphrey. While the Minnesota senator had witnessed up-close poverty, the Massachusetts senator had little exposure to it until he started campaigning in West Virginia.

Kennedy’s experience in West Virginia became a teachable moment for the future president, one that influenced the policies of his administration and the direction for the nation, especially regarding federal attention on Appalachia. The candidate’s exposure to poverty provided motivation for a food stamp proposal and the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), and it helped plant the seeds for a future War on Poverty. Several of those programs, like the food stamp program, survive today.

Kennedy was personally affected by the poverty, poor nutrition, joblessness, and hopelessness he saw firsthand in West Virginia. He spent time passing abandoned miners’ homes, with boards over windows called Eisenhower curtains, and considered it his “education.” Ramie Barker, who would become a senior advisor to West Virginia governor Earl Ray Tomblin, says, “Traveling around here changed him. He learned to become a president.” Barker notes that he “saw wives line up for surplus government food, and he heard about kids who saved their school milk for younger siblings at home.”

During the last week of the campaign Kennedy emphasized “he was glad that he entered the West Virginia primary because it gave him an opportunity to see the plight of men who have lost work because of automation.” Referring to the primary, he said that “This is the best school, the hardest school, and in many ways the most somber school of learning about this problem.”

As Richard Godwin wrote “Kennedy was in West Virginia to win an election. But in that struggle he was learning more about America; about that underside of American life that he had never experienced so personally, intimately.” Goodwin related that midway in the West Virginia primary campaign, Kennedy came to the Washington office and commenting to no one in particular said: “You can’t imagine how those people live down there. I was better off in the war than they are in those coal mines. It’s not right. I’m going to do something about it. If we make it.” Then he added ironically: “Even if they are a bunch of bigots.”

In his televised debate, Kennedy emphasized how his almost five weeks in the Mountain State would impact his presidency by saying “A President can hear about those problems (in West Virginia)—he can read reports—but unless he has spent a month here, seeing it for himself and talking with people, he cannot fully grasp this state’s urgent need for action.” But this recognition of the state and promise of action for the state had an important geographic component as the candidate went on to state that “For America is not just Chicago and Los Angeles—it is Logan and Beckley and Welch as well. The candidate often reminded his audiences that he had been in the state so long, that he learned the geography of the Mountain State. He knew the difference between Charleston and Charles Town; had been the only presidential candidate to have come to Welch three times, or visited Collins High School twice and knew “where Slab Fork is and has been there.” Never before had a presidential contender spent so much time in a state, and it could be argued that never before or since had a future president learned so much.

The experience motivated Kennedy to back up the promises he made to West Virginians during the campaign with concrete public policy programs based on governmental help. Key to these programs was the philosophy that these once proud and able people weren’t poor and malnourished because they deserved it, but because of circumstances beyond their control.

In regard to policy, the contest brought national attention to the economic problems in Appalachia and kindled Kennedy’s interest in fighting rural poverty, which ultimately lead to the creation of a number of initiatives and programs by Lyndon Johnson. But such attention and subsequent action came at a price. The so-called “rediscovery” of white poverty in the upland South brought with it increased attention to stereotypes. Appalachia in general and West Virginia in particular were portrayed negatively in popular culture and mainstream media.

The fourth impact of the primary campaign rests both in its challenge to and perpetuation of stereotypes of the state and region. On the upside, the outcome of the primary undermined outsiders’ low expectations of state residents, who confounded conventional wisdom due to the strong Appalachian value of judging people on an individual basis. After the election, a West Virginia newspaper argued, “Sen. Kennedy’s victory proves what some of us have been trying to say all along. That West Virginia is not the hotbed of religious prejudice some of our distinguished visitors have supposed it to be. We have our religious feelings, to be sure, and here and there they run deep and bitter, but in a purely political campaign, they are not decisive.”

The downside, however, was reflected in reports of West Virginia as an impoverished state, with photographs often showing hard times on gaunt faces. Appalachia had always been victim of such caricatures, but it was made worse in the spring of 1960 by the invasion of the national press with negative coverage that exaggerated the role of religious bigotry while resorting to stereotypes of the region. Charleston reporter L. T. Anderson pointed out “West Virginia was badly portrayed to the nation. It was pictured as a kingdom of defiant, vulgar, gross and stupid bigotry.”

When the Massachusetts senator began his nomination effort, Ben Bradlee of Newsweek asked him at the end of 1959 if he thought he could win. Kennedy answered, “Yes, if I don’t make a single mistake myself and if I don’t get maneuvered into a position where there is no way out.” In other words, he could never finish second in any primary, or get into a situation like Harold Stassen did in 1948, where everything was riding on one event (the Oregon primary) and he blew it. After the Wisconsin primary, the West Virginia contest unexpectedly became that one event that could derail Kennedy’s quest. It became an election that the candidate had to win.