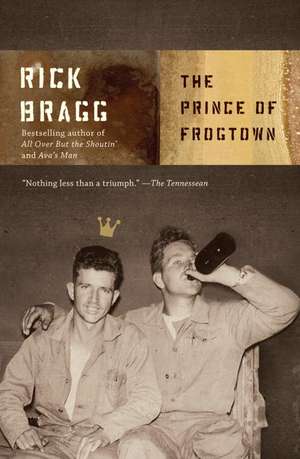

The Prince of Frogtown

Autor Rick Braggen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2009 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Listen Up (2008)

Inspired by Rick Bragg's love for his stepson, The Prince of Frogtown also chronicles his own journey into fatherhood, as he learns to avoid the pitfalls of his forebearers. With candor, insight, and tremendous humor, Bragg seamlessly weaves these luminous narrative threads together and delivers an unforgettable rumination about fathers and sons.

Preț: 98.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.90€ • 19.74$ • 15.61£

18.90€ • 19.74$ • 15.61£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400032686

ISBN-10: 1400032687

Pagini: 255

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400032687

Pagini: 255

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Rick Bragg is the author of two best-selling books, Ava's Man and All Over but the Shoutin'. He lives in Alabama.

Extras

The ditch cleaved frogtown into two realms, and two powerful spirits heldsway,one on each side. One was old, old as the Cross, and the other had aged only a few days in a gallon can. Both had the power to change men’s lives. On one side of the ditch, a packed-in, pleading faithful fell hard to their knees and called the Holy Ghost into their jerking bodies in unknown tongues. On the other side, two boys, too much alike to be anything but brothers, flung open the doors of a black Chevrolet and lurched into the yard of 117 D Street, hallelujahs falling dead around them in the weeds. In the house, a sad-eyed little woman looked out, afraid it might be the law. When your boys are gone you’re always afraid it might be the law. But it was just her two oldest sons, Roy and Troy, floating home inside the bubble of her prayer, still in crumpled, cattin’-around clothes from Saturday night, still a little drunk on Sunday morning. They were fine boys, though, beautiful boys. They were just steps away now, a few steps. She would fry eggs by the platterful and pour black coffee, and be glad they were not in a smoking hulk wrapped around a tree, or at the mercy of the police. She thought sometimes of walking over to the church to see it all, to hear the lovely music, but that would leave her boys and man unsupervised for too long. Her third son was eleven or so then. He could hear the piano ring across the ditch, even hear people shout, but he could smell the liquor that was always in the house on a Sunday and even steal a taste of it when no one was looking, so it was more real.

The holy ghost moved invisible, but they could feel it in the rafters, sense it racing inside the walls. It was as real as a jag of lightning, or an electrical fire.

The preacher stood on a humble, foot-high dais, to show that he did not believe he was better than them. “Do you believe in the Holy

Ghost?” he asked, and they said they did. He preached then of the end of the world, and it was beautiful.

They were still a new denomination then, but had spread rapidly in the last fifty years around a nation of exploited factory workers, coal

miners, and rural and inner-city poor. Here, it was a church of lintheads, pulpwooders and sharecroppers, shoutin’ people, who said

amen like they were throwing a mule shoe. Biblical scholars turned their noses up, calling it hysteria, theatrics, a faith of the illiterate. But in a place where machines ate people alive, faith had to pour even hotter than blood.

It had no steeple, no stained glass, no bell tower, but it was the house of Abraham and Isaac, of Moses and Joshua, of the Lord thy

God. People tithed in Mercury dimes and buffalo nickels, and pews filled with old men who wore ancient black suit coats over overalls,

and young men in short-sleeved dress shirts and clip-on ties. Women sat plain, not one smear of lipstick or daub of makeup on their

faces, and not one scrap of lace at their wrists or necks. Their hair was long, because Paul wrote that “if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her, for her hair is given her for a covering.” Their hair and long dresses were always getting caught in the machines, but it was in the Scripture, so they obeyed. Some wore it pinned up for church, because of the heat, but before it was over hairpins would litter the

floor.

They listened as the preacher laid down a list of sins so complete it left a person no place to go but down.

“They preached it hard, so hard a feller couldn’t live it,” said Homer Barnwell, who went there as a boy.

The people, some gasping from the brown lung, ignored the weakness in their wind and pain in their chests and sang “I’ll Fly Away”

and “Kneel at the Cross” and “That Good Ol’ Gospel Ship.” A woman named Cora Lee Garmon, famous for her range, used to hit

the high notes so hard “the leaders would stand out in her neck,” Homer said.

Then, with the unstoppable momentum of a train going down a grade, the service picked up speed. The Reverend evoked a harsh

God, who turned Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt, and condemned the Children of Israel, who gave their golden earrings to Aaron to fashion Baal, the false god. “I have seen this people,” God told Moses, “and behold, it is a stiff-necked people. Now therefore let me alone, so that my wrath may wax hot against them.”

As children looked with misery on a service without end, the preacher read chapter 2 of the Acts of the Apostles:

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with

one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from

heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house

where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven

tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were

all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other

tongues . . .

The congregants’ eyes were shut tight.

“Do you feel the Spirit?” the Reverend shouted.

Their hands reached high.

“Can you feel the Holy Ghost?”

They answered one by one, in the light of the full Gospel.

“Yeeeeesssss.”

Then, as if they had reached for a sizzling clothesline in the middle of an electrical storm, one by one they began to jerk, convulsing in the grip of unseen power. Others threw their arms open wide, and the Holy Ghost touched them soul by soul.

Some just stood and shivered.

Some danced, spinning.

Some leapt high in the air.

Some wept.

Some shrieked.

Some of the women shook their heads so violently that their hair came free and whipped through the air, three feet long. Hairpins flew.

The Ghost was in them now.

They began to speak in tongues.

The older church people interpreted, and the congregation leaned in, to hear the miracle. It sounded like ancient Hebrew,maybe, a little,

and other times it sounded like nothing they had heard or imagined. They rushed to the front of the church and knelt in a line, facing the

altar, so the preacher could lay his hands on them, and–through the Father, in the presence of the Holy Ghost–make them whole.

One by one, they were slain in the Spirit, and fell backward, some of them, fainting on the floor. The services could last for hours, till the congregants’ stomachs growled. “If it’s goin’ good,” Homer said, “why switch it off ?”

As strong as it was, as close, it was as if sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal, across that ditch.

“We could have by God stayed longer if you’d have brought some damn money,” griped Roy, as they meandered toward the house. It is unclear where they had been that weekend, but apparently they had a real good time. Roy, the prettiest of all of them, leaned against the car for balance, and cussed his older brother a little more.Roy’s eyes were just like my father’s, a bright blue, and his hair was black. He was tall for a Bragg, and the meanest when he drank. He was not a dandy and just threw on his clothes, but was one of those men who would have looked elegant standing in a mudhole.

Troy cussed him back, but cheerfully. He always wore snow-white T-shirts, black pants and black penny loafer shoes, and as he blithely dog-cussed his brother he bent over, took off one loafer and dumped several neatly folded bills into his hand. Then, hopping around on one foot, he waved the bills in his brother’s face.

“You lying son of a bitch,”Roy said.

Troy, his shoe still in his hand, just hopped and grinned, trying not to get his white sock dirty.

He sniffed the money, like it was flowers.

“I’ll kill you,”Roy said.

But they were always threatening to kill somebody.

Troy, in a wobbly pirouette, laughed out loud.

In seconds, they were in the dirt, tearing at clothes and screaming curses, and rolled clear into the middle of D Street, in a whirl of blood

and cinders.

The commotion drew first Velma and then Bobby from inside the house.Velma, unheard and ignored, pleaded for them to stop. Bobby,

on a binge and still dressed only in his long-handles, cackled, hopped, and did a do-si-do.

My father banged through the door and into the yard, and, like a pair of long underwear sucked off a clothesline by a tornado, was carried away by the melee.

In the rising dust, they clubbed each other about the head with their fists, split lips and blacked eyes and bruised ribs. My father, smaller than his brothers, was knocked down and almost out. Velma bent over my father, to make sure he was breathing, and yelled at the

older two: “I’ll call the law.” Then she left walking, to find a telephone.

How many times did Velma make that walk to a borrowed telephone, having to choose between her sons’ freedom and their safety?

My Aunt Juanita, driving through the village, remembers seeing her walking fast down the street. “Her heels was just a’clickin’ on the

road,” she said.

She stopped and, through the window, asked Velma if she was all right.

“The boys is killing each other,” she said.

In the yard, the boys were staggering now, about used-up. The neighbors watched from their porches, but no one got in the way. The

distant scream of a police siren drifted into the yard.Velma had found a telephone.

By the time the police came, the street was empty and quiet in front of 117, the brothers inside, ruining Velma’s washrags with their blood. Bobby had enjoyed himself immensely, and gone a half day without pants of any kind. Velma walked back, her flat shoes clicking slowly now. But her boys were safe, and nothing mattered next to that.

In the aftermath, she cooked a five-pound block of meat loaf, a mountain of fried potatoes, a cauldron of pinto beans, and dishpans of squash and okra–nothing special, just the usual supper for the kin that, every Sunday, trickled in to eat.

It was nothing special, either, that fight, nothing to get all worked up about. The brothers regularly fought in the middle of D Street. “I

watched ’em fight,” said Charles Parker, who lived next door.

Or, as Carlos put it: “You didn’t never ask about that big fight Roy and Troy had, you asked about which one. It happened regular.” It was just part of the rhythm of the week, the rhythm of their lives.

Most lives move to one kind or another. On the coast, they move to tides, and in a factory town they move to an assembly line. For Carlos, a body and fender man and wrecker driver, life moved to the rhythms of the highway, to the voice of the dispatcher on the radio. In the week he cruised slow and easy, but on Friday nights, when drinkers hit the roads, the dispatcher’s voice crackled with possibility. He stomped the accelerator and raced from ditch to ditch, his winch cable whining, yellow lights spinning, mommas crying, ambulances screaming away or, if it was a bad one, not screaming at all.

For his cousins on D Street, it was the bootlegger’s rhythm. “The boys and Uncle Bobby all worked, and only dranked on weekends. They’d get goin’ real good on Friday and still be goin’ on a Sunday. Of course, sometimes they could still be going on a Tuesday, depending on how much liquor they had. They were the best people in the world, gentle people, when they were all right. But all your daddy’s life, on a weekend, there was liquor there in that house.”

In the calm of a Monday, the nights had a warmth and peace in Velma’s house. After work, her extended family gathered in her

kitchen, eating, talking, babies riding on their knees. But mostly, in that quiet, she cooked. “Oh my,” said Carlos, “did she cook.” She

cooked showpiece meals, meals most people only got on Thanksgiving or Christmas Day, and Carlos loved to go see his Aunt Velma in

the calm. “It didn’t matter what time of night or day it was, or even if she had to get out of bed, when you went to Aunt Velma’s house

the first thing she did was ask you, ‘Y’all boys had something to eat?’ It didn’t matter if you’d done eat, ’cause Velma was gonna feed you anyway.”

The iron stove had a cast-iron warmer on the top, and in that warmer would be pork roasts and pork chops and fried chicken, twogallon

pots of butter beans with salt pork, navy beans with ham bone, rattlesnake beans glistening with bacon fat, pans of chicken and dressing, macaroni and cheese, cornbread and cathead biscuits, mounds of mashed potatoes and sweet potatoes, skillets of fried green tomatoes.

She made meat loaf in a washtub, working loaf bread into the meat, onions and spices with her hands. There would be fried pies, apple

and peach, in the warmer, and a banana puddin’ in the icebox. She cooked her pies in a pan the size of a Western Flyer, and she did not

cut you a piece but scooped out a mound, a solid pound of pie.

It was not just food. There was a richness in it, of cream and butter and bacon fat. Her dishes were chipped and her forks were worn, pitted steel, but when people were done the utensils looked like they had been licked clean, and sometimes they were. She taught generations of women to cook, including my own mother, who thinks of her with every shaker of salt. Generations of men, like Carlos, get teary-eyed when they think of her supper table on a random Monday, because they know it will never be that good again.

In the calm of a Tuesday, the mercurial Roy lay on the couch in the living room with a baby asleep on his chest. He would fight an army when he was drinking, fight laughing, bleeding, but sober he was a gentle man. “Whose baby are you?” he always asked, as the infants opened their eyes. “Roy rocked the babies in the rocking chairs, when he was all right,” my mother said. “He would sing, and hum to them, and he would even diaper them–I guarantee you that your daddy never got nowhere near a diaper.” Roy was not married then, and had no children of his own. He just loved babies, and would rock Troy’s children and sing, and hum the part where the bough breaks, and the baby falls.

He was a mechanic, a good one, with a set of paid-for tools. Women chased him. He had everything to live for, on a Tuesday, and no reason to dull his life with liquor, no reason to hide in a whiskey haze.

In the quiet of a Wednesday, Troy walked home from his job at the mill, to tend his birds. In that time and place, it was as noble a job as

being a horse breeder. He opened the coop and stuck his hand in toward the fierce creature inside, eyes yellow, beak sharp as a cat’s

claw, trilling a warning so low it was almost a growl. But it did not draw blood as he reached in and lifted it out.

He would sit on the porch, a cup of Red Diamond coffee on the rail, and stroke its beak, cooing to it, as if he wanted it to understand the

awful sacrifice he was asking it to make. He had one bird that had won seven fights, a remarkable feat in a death sport, and he would run his fingers through its feathers, looking for parasites. He would treat it with Mercurochrome, like a child with a skinned knee, and let it peck corn from his palm. He fed them a mix of vitamins and racing pigeon feed, to make them strong and fast, and spiked their diet with pickling lime, to stanch the bleeding when they were cut.

From the Hardcover edition.

The holy ghost moved invisible, but they could feel it in the rafters, sense it racing inside the walls. It was as real as a jag of lightning, or an electrical fire.

The preacher stood on a humble, foot-high dais, to show that he did not believe he was better than them. “Do you believe in the Holy

Ghost?” he asked, and they said they did. He preached then of the end of the world, and it was beautiful.

They were still a new denomination then, but had spread rapidly in the last fifty years around a nation of exploited factory workers, coal

miners, and rural and inner-city poor. Here, it was a church of lintheads, pulpwooders and sharecroppers, shoutin’ people, who said

amen like they were throwing a mule shoe. Biblical scholars turned their noses up, calling it hysteria, theatrics, a faith of the illiterate. But in a place where machines ate people alive, faith had to pour even hotter than blood.

It had no steeple, no stained glass, no bell tower, but it was the house of Abraham and Isaac, of Moses and Joshua, of the Lord thy

God. People tithed in Mercury dimes and buffalo nickels, and pews filled with old men who wore ancient black suit coats over overalls,

and young men in short-sleeved dress shirts and clip-on ties. Women sat plain, not one smear of lipstick or daub of makeup on their

faces, and not one scrap of lace at their wrists or necks. Their hair was long, because Paul wrote that “if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her, for her hair is given her for a covering.” Their hair and long dresses were always getting caught in the machines, but it was in the Scripture, so they obeyed. Some wore it pinned up for church, because of the heat, but before it was over hairpins would litter the

floor.

They listened as the preacher laid down a list of sins so complete it left a person no place to go but down.

“They preached it hard, so hard a feller couldn’t live it,” said Homer Barnwell, who went there as a boy.

The people, some gasping from the brown lung, ignored the weakness in their wind and pain in their chests and sang “I’ll Fly Away”

and “Kneel at the Cross” and “That Good Ol’ Gospel Ship.” A woman named Cora Lee Garmon, famous for her range, used to hit

the high notes so hard “the leaders would stand out in her neck,” Homer said.

Then, with the unstoppable momentum of a train going down a grade, the service picked up speed. The Reverend evoked a harsh

God, who turned Lot’s wife into a pillar of salt, and condemned the Children of Israel, who gave their golden earrings to Aaron to fashion Baal, the false god. “I have seen this people,” God told Moses, “and behold, it is a stiff-necked people. Now therefore let me alone, so that my wrath may wax hot against them.”

As children looked with misery on a service without end, the preacher read chapter 2 of the Acts of the Apostles:

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with

one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from

heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house

where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven

tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were

all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other

tongues . . .

The congregants’ eyes were shut tight.

“Do you feel the Spirit?” the Reverend shouted.

Their hands reached high.

“Can you feel the Holy Ghost?”

They answered one by one, in the light of the full Gospel.

“Yeeeeesssss.”

Then, as if they had reached for a sizzling clothesline in the middle of an electrical storm, one by one they began to jerk, convulsing in the grip of unseen power. Others threw their arms open wide, and the Holy Ghost touched them soul by soul.

Some just stood and shivered.

Some danced, spinning.

Some leapt high in the air.

Some wept.

Some shrieked.

Some of the women shook their heads so violently that their hair came free and whipped through the air, three feet long. Hairpins flew.

The Ghost was in them now.

They began to speak in tongues.

The older church people interpreted, and the congregation leaned in, to hear the miracle. It sounded like ancient Hebrew,maybe, a little,

and other times it sounded like nothing they had heard or imagined. They rushed to the front of the church and knelt in a line, facing the

altar, so the preacher could lay his hands on them, and–through the Father, in the presence of the Holy Ghost–make them whole.

One by one, they were slain in the Spirit, and fell backward, some of them, fainting on the floor. The services could last for hours, till the congregants’ stomachs growled. “If it’s goin’ good,” Homer said, “why switch it off ?”

As strong as it was, as close, it was as if sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal, across that ditch.

“We could have by God stayed longer if you’d have brought some damn money,” griped Roy, as they meandered toward the house. It is unclear where they had been that weekend, but apparently they had a real good time. Roy, the prettiest of all of them, leaned against the car for balance, and cussed his older brother a little more.Roy’s eyes were just like my father’s, a bright blue, and his hair was black. He was tall for a Bragg, and the meanest when he drank. He was not a dandy and just threw on his clothes, but was one of those men who would have looked elegant standing in a mudhole.

Troy cussed him back, but cheerfully. He always wore snow-white T-shirts, black pants and black penny loafer shoes, and as he blithely dog-cussed his brother he bent over, took off one loafer and dumped several neatly folded bills into his hand. Then, hopping around on one foot, he waved the bills in his brother’s face.

“You lying son of a bitch,”Roy said.

Troy, his shoe still in his hand, just hopped and grinned, trying not to get his white sock dirty.

He sniffed the money, like it was flowers.

“I’ll kill you,”Roy said.

But they were always threatening to kill somebody.

Troy, in a wobbly pirouette, laughed out loud.

In seconds, they were in the dirt, tearing at clothes and screaming curses, and rolled clear into the middle of D Street, in a whirl of blood

and cinders.

The commotion drew first Velma and then Bobby from inside the house.Velma, unheard and ignored, pleaded for them to stop. Bobby,

on a binge and still dressed only in his long-handles, cackled, hopped, and did a do-si-do.

My father banged through the door and into the yard, and, like a pair of long underwear sucked off a clothesline by a tornado, was carried away by the melee.

In the rising dust, they clubbed each other about the head with their fists, split lips and blacked eyes and bruised ribs. My father, smaller than his brothers, was knocked down and almost out. Velma bent over my father, to make sure he was breathing, and yelled at the

older two: “I’ll call the law.” Then she left walking, to find a telephone.

How many times did Velma make that walk to a borrowed telephone, having to choose between her sons’ freedom and their safety?

My Aunt Juanita, driving through the village, remembers seeing her walking fast down the street. “Her heels was just a’clickin’ on the

road,” she said.

She stopped and, through the window, asked Velma if she was all right.

“The boys is killing each other,” she said.

In the yard, the boys were staggering now, about used-up. The neighbors watched from their porches, but no one got in the way. The

distant scream of a police siren drifted into the yard.Velma had found a telephone.

By the time the police came, the street was empty and quiet in front of 117, the brothers inside, ruining Velma’s washrags with their blood. Bobby had enjoyed himself immensely, and gone a half day without pants of any kind. Velma walked back, her flat shoes clicking slowly now. But her boys were safe, and nothing mattered next to that.

In the aftermath, she cooked a five-pound block of meat loaf, a mountain of fried potatoes, a cauldron of pinto beans, and dishpans of squash and okra–nothing special, just the usual supper for the kin that, every Sunday, trickled in to eat.

It was nothing special, either, that fight, nothing to get all worked up about. The brothers regularly fought in the middle of D Street. “I

watched ’em fight,” said Charles Parker, who lived next door.

Or, as Carlos put it: “You didn’t never ask about that big fight Roy and Troy had, you asked about which one. It happened regular.” It was just part of the rhythm of the week, the rhythm of their lives.

Most lives move to one kind or another. On the coast, they move to tides, and in a factory town they move to an assembly line. For Carlos, a body and fender man and wrecker driver, life moved to the rhythms of the highway, to the voice of the dispatcher on the radio. In the week he cruised slow and easy, but on Friday nights, when drinkers hit the roads, the dispatcher’s voice crackled with possibility. He stomped the accelerator and raced from ditch to ditch, his winch cable whining, yellow lights spinning, mommas crying, ambulances screaming away or, if it was a bad one, not screaming at all.

For his cousins on D Street, it was the bootlegger’s rhythm. “The boys and Uncle Bobby all worked, and only dranked on weekends. They’d get goin’ real good on Friday and still be goin’ on a Sunday. Of course, sometimes they could still be going on a Tuesday, depending on how much liquor they had. They were the best people in the world, gentle people, when they were all right. But all your daddy’s life, on a weekend, there was liquor there in that house.”

In the calm of a Monday, the nights had a warmth and peace in Velma’s house. After work, her extended family gathered in her

kitchen, eating, talking, babies riding on their knees. But mostly, in that quiet, she cooked. “Oh my,” said Carlos, “did she cook.” She

cooked showpiece meals, meals most people only got on Thanksgiving or Christmas Day, and Carlos loved to go see his Aunt Velma in

the calm. “It didn’t matter what time of night or day it was, or even if she had to get out of bed, when you went to Aunt Velma’s house

the first thing she did was ask you, ‘Y’all boys had something to eat?’ It didn’t matter if you’d done eat, ’cause Velma was gonna feed you anyway.”

The iron stove had a cast-iron warmer on the top, and in that warmer would be pork roasts and pork chops and fried chicken, twogallon

pots of butter beans with salt pork, navy beans with ham bone, rattlesnake beans glistening with bacon fat, pans of chicken and dressing, macaroni and cheese, cornbread and cathead biscuits, mounds of mashed potatoes and sweet potatoes, skillets of fried green tomatoes.

She made meat loaf in a washtub, working loaf bread into the meat, onions and spices with her hands. There would be fried pies, apple

and peach, in the warmer, and a banana puddin’ in the icebox. She cooked her pies in a pan the size of a Western Flyer, and she did not

cut you a piece but scooped out a mound, a solid pound of pie.

It was not just food. There was a richness in it, of cream and butter and bacon fat. Her dishes were chipped and her forks were worn, pitted steel, but when people were done the utensils looked like they had been licked clean, and sometimes they were. She taught generations of women to cook, including my own mother, who thinks of her with every shaker of salt. Generations of men, like Carlos, get teary-eyed when they think of her supper table on a random Monday, because they know it will never be that good again.

In the calm of a Tuesday, the mercurial Roy lay on the couch in the living room with a baby asleep on his chest. He would fight an army when he was drinking, fight laughing, bleeding, but sober he was a gentle man. “Whose baby are you?” he always asked, as the infants opened their eyes. “Roy rocked the babies in the rocking chairs, when he was all right,” my mother said. “He would sing, and hum to them, and he would even diaper them–I guarantee you that your daddy never got nowhere near a diaper.” Roy was not married then, and had no children of his own. He just loved babies, and would rock Troy’s children and sing, and hum the part where the bough breaks, and the baby falls.

He was a mechanic, a good one, with a set of paid-for tools. Women chased him. He had everything to live for, on a Tuesday, and no reason to dull his life with liquor, no reason to hide in a whiskey haze.

In the quiet of a Wednesday, Troy walked home from his job at the mill, to tend his birds. In that time and place, it was as noble a job as

being a horse breeder. He opened the coop and stuck his hand in toward the fierce creature inside, eyes yellow, beak sharp as a cat’s

claw, trilling a warning so low it was almost a growl. But it did not draw blood as he reached in and lifted it out.

He would sit on the porch, a cup of Red Diamond coffee on the rail, and stroke its beak, cooing to it, as if he wanted it to understand the

awful sacrifice he was asking it to make. He had one bird that had won seven fights, a remarkable feat in a death sport, and he would run his fingers through its feathers, looking for parasites. He would treat it with Mercurochrome, like a child with a skinned knee, and let it peck corn from his palm. He fed them a mix of vitamins and racing pigeon feed, to make them strong and fast, and spiked their diet with pickling lime, to stanch the bleeding when they were cut.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Nothing less than a triumph.”—The Tennessean“Powerful.... [Bragg is] a storyteller on a par with Pat Conroy.” —Denver Post“Rick Bragg has made of the dark shadow in his life a figure of flesh and blood, passion and tragedy, and a father, at last, whose memory he can live with. And that is no small thing for any man to do.” —The New York Times Book Review“Bragg writes in that sumptuous, multilayered, image-rich Southern yarn-spinning manner that seduces as fast as you can read it. It unwinds beautifully.”—The Providence Journal“With The Prince of Frogtown, Bragg finds a heartening truth: He is not doomed to take up the defects of his forebears but learns instead to use them as a compass.... Readers will relish the journey.”—Rocky Mountain News“Vivid.... An evocative family memoir.”—Boston Globe“By turns gut-wrenching, hilarious and heartbreaking.... A way of looking hard at the past in order to break free of it.” —St. Petersburg Times“Bragg crafts flowing sentences that vividly describe the southern Appalachian landscape and ways of life both old and new. . . . His father’s story walks the line between humorous and heartbreaking . . . This book, much like his previous two memoirs, is lush with narratives about manhood, fathers and sons, families and the changing face of the rural South.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)“Smooth and rich as bourbon.”—Kirkus“Bragg continues in the vein of his legendary storytelling, breathing life into a father he barely knew while learning to love a son.”—Library Journal

Descriere

With candor, insight, and tremendous humor, Bragg closes his circle of family stories in an unforgettable tale about fathers and sons.

Premii

- Listen Up Editor's Choice, 2008