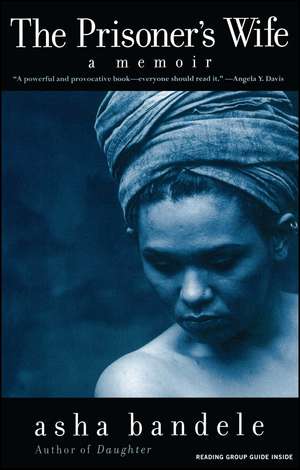

The Prisoner's Wife

Autor Asha Bandeleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 19 noi 2000

Preț: 90.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.33€ • 18.82$ • 14.56£

17.33€ • 18.82$ • 14.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780671021481

ISBN-10: 0671021486

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

ISBN-10: 0671021486

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Notă biografică

Asha Bandele served as features editor and writer for Essence magazine, and a Revson Fellow at Columbia University. She is the author of the memoir The Prisoner's Wife and a collection of poetry. She lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her daughter.

Extras

Chapter One: This Is a Love Story

This is a love story like every love story I had always known, like no love story I could ever have imagined. It's everything beautiful -- bright colors, candle-scented rooms, orange silk, and lavender amethyst. It's everything grotesque, disfigured. It's long twisting wounds, open and unhealed, nerves pricked raw, exposed.

This is a love story, awake and alive. It's a breathing document, a living witness. It's human possibility, hope, and connection. It's a gathering of Spirit, the claiming of dreams. It's an Alvin Ailey dance, a rainbow roun' mah shoulder. It's a freedom song, a 12-string guitar, a Delta blues song. This story is a reprieve.

This is a love story, threadbare and used up, yet sometimes fat, weighty, stretched out of shape. It's polyester, this story, man-made, trying to be pretty, not quite making it. This is a story desperate to hold itself together. This is a story with patches in the knees.

This is a love story, my love story and thousands of other women's love story. It's a story that's known, documented, photographed, videotaped, audiotaped, filed, photocopied, watched over, studied, caricatured, questioned, researched, and noted.

This is a love story. It's the one we keep close, sheltering it from judgment. It's lovers denied at family dinners and at office parties. It's secret glances at Polaroid pictures. It's whispered names. This is a story hidden within midnight bus rides and 5:00 A.M. van rides, behind metal detectors, electronic doors, and steel slamming against steel.

This is a love story, the one not generally discussed in polite or even public conversation. But if there's one thing that I do know about myself, it's that I know I hate secrets, that secrets mean shame, and that I am not now, nor will I ever be, ashamed that I am a woman who has loved someone, and that someone loved me.

And even though so many people have asked me if I have lost my mind, if I am lonely, or desperate. Even though so many people have wondered if I was having a crisis, or determined that I was just going through a phase, I will continue loving the man I am loving. I will love him even though he's got an ugly past, skeletons, and sorrow. Even though he doesn't have a great job or position or power, and even though he's a prisoner at a maximum-security correctional facility, which my husband, Rashid, is, I will continue loving him.

And this is our story.

The first time I ever went into a prison, it was for a class I was taking on the relationship between Black people and incarceration in the United States. Months later, long after final exams had been taken and grades received, my former professor called me and asked if I would come with him and a few other people to a place called Eastern Correctional Facility in upstate New York. It was just about eighty miles from Brooklyn, where I lived. He wanted me, he said, to participate in a Black History Month program.

Don't you write poems? he asked.

You could read your poetry, he said.

I agreed and we all went to do the program, and this was how we met, Rashid and I, convict and student, gangster and poet, resident host and visiting performer.

Rashid is fine as hell, which I tried not to but couldn't help noticing the very first time I saw him. He looks like this beautifully symmetrical collaboration between Africa and India. He isn't huge, not an overwhelming presence, contrary to the usual celluloid interpretation of Black prisoners. Rashid is 5'7", with a brave smile and bright eyes. He is, I remember thinking this then, just the right size, and I could look directly at him, nearly eye to eye. His voice, which was never loud, told a story of a transplanted Afro-Caribbean.

Where are you from? I wanted to know.

The Boogie Down, he responded, meaning the South Bronx.

And before?

Oh, oh, he said, understanding my question. Guyana. South America. It's the most beautiful place in the world. That's a hell of a thing in one life, huh? To have seen the most beautiful place in the world and the most horrible place. And I'm not even thirty yet!

After that, a number of other men came over to me to tell me how much they enjoyed my performance, and would I be willing to read their work, when was I coming back up, could they write to me to discuss poetry, did I know I reminded them of this sister they used to know back in the day? In the midst of these questions, Rashid left me. I watched him as he walked across the huge auditorium where the program was being held. He weaved easily through the nearly one hundred men gathered there, through the orange chairs, across the stage, the back of it, and found another guest to talk to, a poet like me. A very talented poet, I should say, and a very attractive one. I waited for him to come back over to me. I tried to will him to come back over to me, but finally I was left there annoyed because Rashid did not return until it was time to say good-bye.

After we were in love, Rashid would tell me that it was me, my fault, that I was hard to approach. He told me that while I was an animated and exciting performer, offstage I was quiet, withdrawn, cool and distant.

Besides, he admits now, through a series of childlike giggles, every dude knows when you really want to talk to a sister, you don't step to her directly. You step to her friend, and that's what I did. I talked to that other sister, the poet who performed before you, because that way I knew I'd get your attention. I mean, what I'd look like trying to talk to you when all of them other dudes were running they game on you? You know what I'm saying?

Rashid is so pleased with himself as he tells me this story five years after our first encounter. After all, in the moment of his confession, we are in a visiting room, and I lie, as fitted as possible, in the crook of his arms. And in that moment, despite every hurting and hell I have had to endure to love this man, there is no other place that I would rather be.

When we began, I was twenty-five, a student and organizer, a wife on the verge of divorce from my first husband, a poet full of secrets and sadness, an emerging woman hampered by insecurities and anger, a human being fighting off loneliness while craving solitude, needing an open love, long honest discussions, a quiet touching at my core.

When we began, he was twenty-nine, inmate number 83*****, a convicted killer doing twenty years with life on the back, a model prisoner, a program coordinator, the father of a nine-year-old boy he had never been able to raise, a lawyer without a law degree, a devoted Muslim, a man on the verge of divorce from his first wife, a human being fighting off loneliness while craving solitude, needing an open love, long honest discussions, a quiet touching at his core.

We were exactly the same and we were completely different.

We were never meant to be together.

We were always meant to save each other.

Copyright © 1999 by asha bandele

This is a love story like every love story I had always known, like no love story I could ever have imagined. It's everything beautiful -- bright colors, candle-scented rooms, orange silk, and lavender amethyst. It's everything grotesque, disfigured. It's long twisting wounds, open and unhealed, nerves pricked raw, exposed.

This is a love story, awake and alive. It's a breathing document, a living witness. It's human possibility, hope, and connection. It's a gathering of Spirit, the claiming of dreams. It's an Alvin Ailey dance, a rainbow roun' mah shoulder. It's a freedom song, a 12-string guitar, a Delta blues song. This story is a reprieve.

This is a love story, threadbare and used up, yet sometimes fat, weighty, stretched out of shape. It's polyester, this story, man-made, trying to be pretty, not quite making it. This is a story desperate to hold itself together. This is a story with patches in the knees.

This is a love story, my love story and thousands of other women's love story. It's a story that's known, documented, photographed, videotaped, audiotaped, filed, photocopied, watched over, studied, caricatured, questioned, researched, and noted.

This is a love story. It's the one we keep close, sheltering it from judgment. It's lovers denied at family dinners and at office parties. It's secret glances at Polaroid pictures. It's whispered names. This is a story hidden within midnight bus rides and 5:00 A.M. van rides, behind metal detectors, electronic doors, and steel slamming against steel.

This is a love story, the one not generally discussed in polite or even public conversation. But if there's one thing that I do know about myself, it's that I know I hate secrets, that secrets mean shame, and that I am not now, nor will I ever be, ashamed that I am a woman who has loved someone, and that someone loved me.

And even though so many people have asked me if I have lost my mind, if I am lonely, or desperate. Even though so many people have wondered if I was having a crisis, or determined that I was just going through a phase, I will continue loving the man I am loving. I will love him even though he's got an ugly past, skeletons, and sorrow. Even though he doesn't have a great job or position or power, and even though he's a prisoner at a maximum-security correctional facility, which my husband, Rashid, is, I will continue loving him.

And this is our story.

The first time I ever went into a prison, it was for a class I was taking on the relationship between Black people and incarceration in the United States. Months later, long after final exams had been taken and grades received, my former professor called me and asked if I would come with him and a few other people to a place called Eastern Correctional Facility in upstate New York. It was just about eighty miles from Brooklyn, where I lived. He wanted me, he said, to participate in a Black History Month program.

Don't you write poems? he asked.

You could read your poetry, he said.

I agreed and we all went to do the program, and this was how we met, Rashid and I, convict and student, gangster and poet, resident host and visiting performer.

Rashid is fine as hell, which I tried not to but couldn't help noticing the very first time I saw him. He looks like this beautifully symmetrical collaboration between Africa and India. He isn't huge, not an overwhelming presence, contrary to the usual celluloid interpretation of Black prisoners. Rashid is 5'7", with a brave smile and bright eyes. He is, I remember thinking this then, just the right size, and I could look directly at him, nearly eye to eye. His voice, which was never loud, told a story of a transplanted Afro-Caribbean.

Where are you from? I wanted to know.

The Boogie Down, he responded, meaning the South Bronx.

And before?

Oh, oh, he said, understanding my question. Guyana. South America. It's the most beautiful place in the world. That's a hell of a thing in one life, huh? To have seen the most beautiful place in the world and the most horrible place. And I'm not even thirty yet!

After that, a number of other men came over to me to tell me how much they enjoyed my performance, and would I be willing to read their work, when was I coming back up, could they write to me to discuss poetry, did I know I reminded them of this sister they used to know back in the day? In the midst of these questions, Rashid left me. I watched him as he walked across the huge auditorium where the program was being held. He weaved easily through the nearly one hundred men gathered there, through the orange chairs, across the stage, the back of it, and found another guest to talk to, a poet like me. A very talented poet, I should say, and a very attractive one. I waited for him to come back over to me. I tried to will him to come back over to me, but finally I was left there annoyed because Rashid did not return until it was time to say good-bye.

After we were in love, Rashid would tell me that it was me, my fault, that I was hard to approach. He told me that while I was an animated and exciting performer, offstage I was quiet, withdrawn, cool and distant.

Besides, he admits now, through a series of childlike giggles, every dude knows when you really want to talk to a sister, you don't step to her directly. You step to her friend, and that's what I did. I talked to that other sister, the poet who performed before you, because that way I knew I'd get your attention. I mean, what I'd look like trying to talk to you when all of them other dudes were running they game on you? You know what I'm saying?

Rashid is so pleased with himself as he tells me this story five years after our first encounter. After all, in the moment of his confession, we are in a visiting room, and I lie, as fitted as possible, in the crook of his arms. And in that moment, despite every hurting and hell I have had to endure to love this man, there is no other place that I would rather be.

When we began, I was twenty-five, a student and organizer, a wife on the verge of divorce from my first husband, a poet full of secrets and sadness, an emerging woman hampered by insecurities and anger, a human being fighting off loneliness while craving solitude, needing an open love, long honest discussions, a quiet touching at my core.

When we began, he was twenty-nine, inmate number 83*****, a convicted killer doing twenty years with life on the back, a model prisoner, a program coordinator, the father of a nine-year-old boy he had never been able to raise, a lawyer without a law degree, a devoted Muslim, a man on the verge of divorce from his first wife, a human being fighting off loneliness while craving solitude, needing an open love, long honest discussions, a quiet touching at his core.

We were exactly the same and we were completely different.

We were never meant to be together.

We were always meant to save each other.

Copyright © 1999 by asha bandele

Recenzii

Angela Y. Davis A powerful and provocative book -- everyone should read it.

Nikki Giovanni It is not easy to trust your heart, but here is a love story. The Prisoner's Wife takes us through not the dungeon of emotions, but the sunshine of hope. If we can continue to find a reason to care, we can all be saved. This book needs to be read by anyone who has...paid a price for love.

Booklist (starred review) asha bandele's writing soars with emotion. And the reader's emotions soar as well, not because of a shared experience but because her highly polished and skillful writing makes one feel her pain and joy. This is a romantic but realistic story, told with a directness and honesty that makes us know that however impossible the problems asha and Rashid face, we can question neither her motives nor sanity.

Nikki Giovanni It is not easy to trust your heart, but here is a love story. The Prisoner's Wife takes us through not the dungeon of emotions, but the sunshine of hope. If we can continue to find a reason to care, we can all be saved. This book needs to be read by anyone who has...paid a price for love.

Booklist (starred review) asha bandele's writing soars with emotion. And the reader's emotions soar as well, not because of a shared experience but because her highly polished and skillful writing makes one feel her pain and joy. This is a romantic but realistic story, told with a directness and honesty that makes us know that however impossible the problems asha and Rashid face, we can question neither her motives nor sanity.

Descriere

The intensely moving story of a young black poet who marries a prisoner convicted of murder. This lyrical memoir attests to the redemptive power of love, even when it is found behind barbed wire and gun towers.