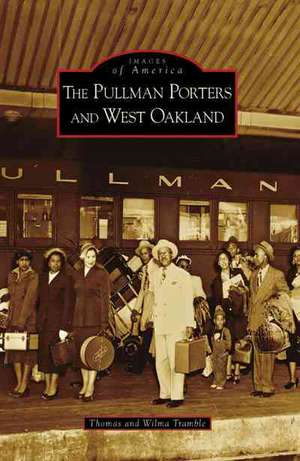

The Pullman Porters and West Oakland: Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

Autor Thomas Tramble, Wilma Trambleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2007

metropolitan area. The catalyst that transformed this neighborhood from a transcontinental rail terminal into a true settlement was the arrival of the railroad porters, employed by the Pullman Palace Car Company as early as 1867. After years of struggling in labor battles and negotiations, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union became the first African American-led union to sign a contract with a large American company. The union's West Coast headquarters were established at Fifth and Wood Streets in West Oakland. Soon families,

benevolent societies, and churches followed, and a true community came into being.

Din seria Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

-

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 133.00 lei

Preț: 133.00 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 127.39 lei

Preț: 127.39 lei -

Preț: 133.00 lei

Preț: 133.00 lei -

Preț: 133.00 lei

Preț: 133.00 lei -

Preț: 133.17 lei

Preț: 133.17 lei -

Preț: 133.41 lei

Preț: 133.41 lei -

Preț: 117.50 lei

Preț: 117.50 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 131.72 lei

Preț: 131.72 lei -

Preț: 117.72 lei

Preț: 117.72 lei -

Preț: 128.26 lei

Preț: 128.26 lei -

Preț: 132.54 lei

Preț: 132.54 lei -

Preț: 128.26 lei

Preț: 128.26 lei -

Preț: 117.72 lei

Preț: 117.72 lei -

Preț: 132.13 lei

Preț: 132.13 lei -

Preț: 127.20 lei

Preț: 127.20 lei -

Preț: 133.41 lei

Preț: 133.41 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 127.20 lei

Preț: 127.20 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 127.20 lei

Preț: 127.20 lei -

Preț: 132.76 lei

Preț: 132.76 lei -

Preț: 120.40 lei

Preț: 120.40 lei -

Preț: 127.39 lei

Preț: 127.39 lei -

Preț: 127.61 lei

Preț: 127.61 lei -

Preț: 133.00 lei

Preț: 133.00 lei -

Preț: 136.28 lei

Preț: 136.28 lei -

Preț: 133.17 lei

Preț: 133.17 lei -

Preț: 118.31 lei

Preț: 118.31 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 133.17 lei

Preț: 133.17 lei -

Preț: 133.17 lei

Preț: 133.17 lei -

Preț: 133.41 lei

Preț: 133.41 lei -

Preț: 133.41 lei

Preț: 133.41 lei -

Preț: 133.00 lei

Preț: 133.00 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 133.00 lei

Preț: 133.00 lei -

Preț: 133.41 lei

Preț: 133.41 lei -

Preț: 131.72 lei

Preț: 131.72 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 128.02 lei

Preț: 128.02 lei -

Preț: 131.94 lei

Preț: 131.94 lei -

Preț: 176.10 lei

Preț: 176.10 lei -

Preț: 118.13 lei

Preț: 118.13 lei

Preț: 133.17 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.49€ • 26.54$ • 21.54£

25.49€ • 26.54$ • 21.54£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780738547893

ISBN-10: 0738547891

Pagini: 127

Dimensiuni: 166 x 234 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Arcadia Publishing (SC)

Seria Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

ISBN-10: 0738547891

Pagini: 127

Dimensiuni: 166 x 234 x 9 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Arcadia Publishing (SC)

Seria Images of America (Arcadia Publishing)

Descriere

A hub of transportation and industry since the mid-19th century, West Oakland is today a vital commercial conduit and an inimitably distinct and diverse community within the Greater Oakland

metropolitan area. The catalyst that transformed this neighborhood from a transcontinental rail terminal into a true settlement was the arrival of the railroad porters, employed by the Pullman Palace Car Company as early as 1867. After years of struggling in labor battles and negotiations, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union became the first African Americanaled union to sign a contract with a large American company. The unionas West Coast headquarters were established at Fifth and Wood Streets in West Oakland. Soon families,

benevolent societies, and churches followed, and a true community came into being.

metropolitan area. The catalyst that transformed this neighborhood from a transcontinental rail terminal into a true settlement was the arrival of the railroad porters, employed by the Pullman Palace Car Company as early as 1867. After years of struggling in labor battles and negotiations, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Union became the first African Americanaled union to sign a contract with a large American company. The unionas West Coast headquarters were established at Fifth and Wood Streets in West Oakland. Soon families,

benevolent societies, and churches followed, and a true community came into being.

Recenzii

Title:

Author: Heidi Benson

Publisher: San Francisco Chronicle

Date: 2/11/2009

On his first day of work on a passenger train in 1943, James Smith didn't get a chance to drink in the landscape on the run from Los Angeles to Portland, OR.

He was deep inside the galley of the dining car.

"I'll never forget that trip," said Smith, 83, who now lives just north of Los Angeles. "I never saw so many dishes in my whole life."

Smith worked his way up, became a waiter - earning tips on top of his salary of 36 cents an hour - and put himself through college. When he left the railroad, he was hired as a civil engineer for the city of Los Angeles, where he worked as a surveyor for 30 years.

His story is emblematic of the role the railroads and a railroad union played in building a foundation for America's black middle class.

Smith was one of five retired railroad employees from the West honored Tuesday morning in a ceremony at the Oakland Amtrak station at Jack London Square. The event was sponsored by Amtrak and the A. Philip Randolph/Pullman Porter Museum in Chicago.

"The self-imposed standard of excellence of the porters made people in the black community very proud," the museum's director, Lyn Hughes, said from the podium. "They planted seeds of confidence for generations to come."

These were the property owners, the business owners, the men who insisted their children go to college, Hughes said, noting that many noteworthy African Americans, from Thurgood Marshall to Malcolm X, worked as Pullman porters in their youth.

The legacy began in 1867-68, when Chicago industrialist George Pullman established the Pullman PalaceCar Co. to build railroad cars with sleeping berths. These Pullman Sleeping Cars, known as "rolling hotels," attracted wealthy business travelers who expected high levels of service.

George Pullman hired newly freed slaves to work as porters, and by the company's heyday in the 1920s, the Pullman Co. was one of the largest employers of African Americans in the nation.

African American union

Hours were long and pay was low until the first African American union - the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters - was founded in 1925 by A. Philip Randolph, who became a powerful leader in the civil rights movement.

In front of the Oakland Amtrak station stands a statue of the vice president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, C.L. Dellums, the Oakland-based labor and civil rights leader and the late uncle of Oakland Mayor Ron Dellums.

In recent years, Mayor Dellums memorably has called the Pullman porters the "astronauts" of the black community.

The comparison is apt, because working on the railroad allowed porters to see great swaths of the country and to meet people from all over the world. They were exposed to new ideas, new music and a broad range of newspapers, magazines and books. Equally, their influence was felt wherever they stepped off the train.

"Porters spread the word," said Leon F. Litwack, a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of history and author of "Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery," winner of the 1980 Pulitzer Prize for history.

"When they went into the South, they took along copies of the Chicago Defender, the most important black newspaper in America," Litwack said. "They helped to publicize theatrocities still taking place in the South, and they told Southern blacks there were alternatives."

Some railroad workers witnessed violence themselves, including Troy Walker, 90, a former dining-car waiter and supervisor who rode the train from his home in Seattle to attend Tuesday's tribute. As a child, Walker survived the Tulsa race riot of 1921, the worst in U.S. history, in which 35 city blocks burned to the ground.

"My parents got us out of there, moved us to Kansas City, Kan.," he recalled. "There was prejudice there, too." He soon moved north to Chicago, where he began work on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad in 1944.

"That job built character," Walker said. "It helped me learn that I could better myself by doing the right thing - for my passengers, for my fellow workers, for my family."

Three generations

Walker met the son of one of his fellow workers, Thomas Henry Gray, 71, on the train trip to Oakland. A chair-car attendant on the Santa Fe from 1955 to '59, Gray also makes his home in Seattle.

"I represent three generations of railroad workers," Gray said from the podium.

His grandfather was a brakeman and a porter. His father, Thomas Jefferson Gray, was a porter for 36 years. Both were members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Together, they paved the way for the younger Gray, who graduated from college in 1961 and worked for Boeing Aircraft as an electrical engineer for 32 years.

"My career is a result of having the guidance of people who worked for the railroad," said Gray, who brought his 92-year-old mother to the Oakland event.

"I was lucky," he said. "I went from trains to planes."

To learn more

The A. Philip Randolph / Pullman Porter Museum: ( www.aphiliprandolphmuseum.com)10406 S. Maryland Ave., Chicago 60628; (773) 928-3935.

"The Pullman Porters and West Oakland": A book by Thomas and Wilma Tramble, Arcadia Publishing (www.arcadiapublishing.com), 2007.

Author: Heidi Benson

Publisher: San Francisco Chronicle

Date: 2/11/2009

On his first day of work on a passenger train in 1943, James Smith didn't get a chance to drink in the landscape on the run from Los Angeles to Portland, OR.

He was deep inside the galley of the dining car.

"I'll never forget that trip," said Smith, 83, who now lives just north of Los Angeles. "I never saw so many dishes in my whole life."

Smith worked his way up, became a waiter - earning tips on top of his salary of 36 cents an hour - and put himself through college. When he left the railroad, he was hired as a civil engineer for the city of Los Angeles, where he worked as a surveyor for 30 years.

His story is emblematic of the role the railroads and a railroad union played in building a foundation for America's black middle class.

Smith was one of five retired railroad employees from the West honored Tuesday morning in a ceremony at the Oakland Amtrak station at Jack London Square. The event was sponsored by Amtrak and the A. Philip Randolph/Pullman Porter Museum in Chicago.

"The self-imposed standard of excellence of the porters made people in the black community very proud," the museum's director, Lyn Hughes, said from the podium. "They planted seeds of confidence for generations to come."

These were the property owners, the business owners, the men who insisted their children go to college, Hughes said, noting that many noteworthy African Americans, from Thurgood Marshall to Malcolm X, worked as Pullman porters in their youth.

The legacy began in 1867-68, when Chicago industrialist George Pullman established the Pullman PalaceCar Co. to build railroad cars with sleeping berths. These Pullman Sleeping Cars, known as "rolling hotels," attracted wealthy business travelers who expected high levels of service.

George Pullman hired newly freed slaves to work as porters, and by the company's heyday in the 1920s, the Pullman Co. was one of the largest employers of African Americans in the nation.

African American union

Hours were long and pay was low until the first African American union - the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters - was founded in 1925 by A. Philip Randolph, who became a powerful leader in the civil rights movement.

In front of the Oakland Amtrak station stands a statue of the vice president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, C.L. Dellums, the Oakland-based labor and civil rights leader and the late uncle of Oakland Mayor Ron Dellums.

In recent years, Mayor Dellums memorably has called the Pullman porters the "astronauts" of the black community.

The comparison is apt, because working on the railroad allowed porters to see great swaths of the country and to meet people from all over the world. They were exposed to new ideas, new music and a broad range of newspapers, magazines and books. Equally, their influence was felt wherever they stepped off the train.

"Porters spread the word," said Leon F. Litwack, a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of history and author of "Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery," winner of the 1980 Pulitzer Prize for history.

"When they went into the South, they took along copies of the Chicago Defender, the most important black newspaper in America," Litwack said. "They helped to publicize theatrocities still taking place in the South, and they told Southern blacks there were alternatives."

Some railroad workers witnessed violence themselves, including Troy Walker, 90, a former dining-car waiter and supervisor who rode the train from his home in Seattle to attend Tuesday's tribute. As a child, Walker survived the Tulsa race riot of 1921, the worst in U.S. history, in which 35 city blocks burned to the ground.

"My parents got us out of there, moved us to Kansas City, Kan.," he recalled. "There was prejudice there, too." He soon moved north to Chicago, where he began work on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad in 1944.

"That job built character," Walker said. "It helped me learn that I could better myself by doing the right thing - for my passengers, for my fellow workers, for my family."

Three generations

Walker met the son of one of his fellow workers, Thomas Henry Gray, 71, on the train trip to Oakland. A chair-car attendant on the Santa Fe from 1955 to '59, Gray also makes his home in Seattle.

"I represent three generations of railroad workers," Gray said from the podium.

His grandfather was a brakeman and a porter. His father, Thomas Jefferson Gray, was a porter for 36 years. Both were members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

Together, they paved the way for the younger Gray, who graduated from college in 1961 and worked for Boeing Aircraft as an electrical engineer for 32 years.

"My career is a result of having the guidance of people who worked for the railroad," said Gray, who brought his 92-year-old mother to the Oakland event.

"I was lucky," he said. "I went from trains to planes."

To learn more

The A. Philip Randolph / Pullman Porter Museum: ( www.aphiliprandolphmuseum.com)10406 S. Maryland Ave., Chicago 60628; (773) 928-3935.

"The Pullman Porters and West Oakland": A book by Thomas and Wilma Tramble, Arcadia Publishing (www.arcadiapublishing.com), 2007.