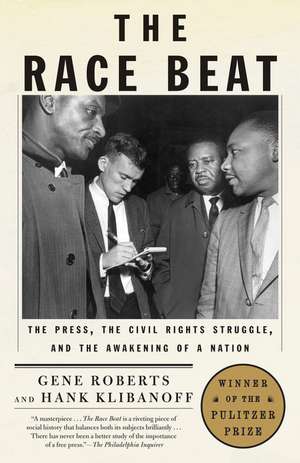

The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation

Autor Gene Roberts, Hank Klibanoffen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2007

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Pulitzer Prize (2007)

Roberts and Klibanoff draw on private correspondence, notes from secret meetings, unpublished articles, and interviews to show how a dedicated cadre of newsmen—black and white—revealed to a nation its most shameful shortcomings that compelled its citizens to act. Meticulously researched and vividly rendered, The Race Beat is an extraordinary account of one of the most calamitous periods in our nation’s history, as told by those who covered it.

Preț: 83.71 lei

Preț vechi: 97.45 lei

-14% Nou

Puncte Express: 126

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.02€ • 16.77$ • 13.25£

16.02€ • 16.77$ • 13.25£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780679735656

ISBN-10: 0679735658

Pagini: 518

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.52 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0679735658

Pagini: 518

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.52 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Recenzii

“A masterpiece . . . The Race Beat is a riveting piece of social history that balances both its subjects brilliantly . . . There has never been a better study of the importance of a free press.”—The Philadelphia Inquirer“Fascinating. . . . Just when you think there's nothing left to say about the civil rights movement, [The Race Beat] pulls you back in.” —The Los Angeles Times“The Race Beat has good characters, good yarns and good thinking. Just as important, though, it’s got a good heart.” —Newsweek “Research for The Race Beat is meticulous, uncovering many facts that have gone unreported in other books about the movement . . . proves a necessary addition to anyone interested in learning more about the movement and the journalists whose work helped transform the South and, indeed, the nation.” —Chicago Sun-Times

Notă biografică

Gene Roberts is a retired journalism professor at the University of Maryland, College Park. He was a reporter and editor with the Detroit Free Press, The Raleigh, N.C., News & Observer, Norfolk Virginian-Pilot and The Goldsboro News-Argus before joining The New York Times in 1965, where until 1972 he served as chief Southern and civil rights correspondent, chief war correspondent in South Vietnam, and national editor. During his 18 years as executive editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, his staff won 17 Pulitzer Prizes. He later became managing editor of the Times.A native of Alabama, Hank Klibanoff is the Managing editor/news at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He is the former Deputy Managing Editor for ThePhiladelphia Inquirer, where he worked for 20 years. He was also a reporter for three years at the Boston Globe and six years in Mississippi for The Daily Herald, South Mississippi Sun (now the Sun-Herald) and the Greenville Delta Democrat Times.

Extras

Chapter 1

An American Dilemma:

“An Astonishing Ignorance . . .”

The winter of 1940 was a cruel one for Gunnar Myrdal, and spring was shaping up even worse. He was in the United States, finishing the research on the most comprehensive study yet of race relations and the condition of Negroes in America. But he was having trouble reaching conclusions, and he struggled to outline and conceptualize the writing. “The whole plan is now in danger of breaking down,” he wrote the Carnegie Foundation, which was underwriting his project.

What’s more, the gathering crisis in Europe had thrown him into a depression; he feared for the very existence of his native Sweden. In April, Nazi Germany had invaded Denmark and Norway. Myrdal believed Sweden would be next. He put aside more than two years of work by 125 researchers and began arranging passage home for himself, his wife, Alva, and their three children. He and Alva wanted to fight alongside their countrymen if the worst should come. The boat he found, the Mathilda Thorden, a Finnish freighter, was laden with explosives, and the captain tried to dissuade the Myrdals from boarding the dangerous ship. When this failed, the captain jokingly urged Myrdal to look on the bright side. He would not have to worry about his family freezing to death in icy waters. If German U-boats attacked, the resulting explosion would almost certainly kill everyone instantly.

The U-boats did not attack, and the Myrdals arrived in Sweden only to be appalled by what was happening there. Rather than preparing for war with Germany, the Swedish government was seeking an accommodation with the Nazis.

Knowing that Germany was monitoring the Swedish press for anti-German sentiment, the government first confiscated copies of anti-Nazi newspapers; then, emboldened, it interfered with the distribution of one of the nation’s most important dailies, Göteborgs Handelstidning. This, Myrdal believed, could not happen in America. He was outraged. “The press is strangled,” he wrote to a Swedish friend in the United States. “Nothing gets written about Germany. News is suppressed.”1

There and then, Myrdal’s understanding of America and its race relations became crystallized. In a book that quickly took precedence over his Carnegie project, then became its seed, Gunnar and Alva Myrdal wrote Kontakt med Amerika (Contact with America), which was crafted largely to rally Swedish resistance against Hitler. In Kontakt, published in 1941, the Myrdals argued that Swedes had much to learn from America about democracy, dialogue, and self-criticism. “The secret,” they wrote, “is that America, ahead of every other country in the whole Western world, large or small, has a living system of expressed ideals for human cooperation which is unified, stable and clearly formulated.”2 The Carnegie project, they added, was evidence of America’s willingness to sanction a sweeping examination and discussion of a national problem.

Almost all of America’s citizens, the Myrdals said, believed in free speech and a free press. Americans respected other viewpoints even when they strongly disagreed. As a result, diverse ethnic groups were living with one another in peace while Europe was tearing itself apart.

Before writing Kontakt, Myrdal didn’t have the insight or context he needed for his weightier book on race in America. Nor did he have the words he felt would serve as the road map to change. Three years earlier, in 1938, he had reached the South, the dark side of the moon. There, he had found an enigmatic, sometimes exotic, always deeply divided and repressive society whose behavior was known to, but overlooked by, the world beyond. In pursuit of an understanding and insight that was still beyond his grasp, his immersion had been total, the details of his discoveries had been staggering, and he had come to a point where he was no longer horrified by the pathology of racism or stunned by the cruelty and pervasiveness of discrimination. He had found himself fascinated by the way an entire social order had been built, and rationalized, around race.

By early 1940, Myrdal frequently found himself feeling oddly optimistic about attitudes he found despicable, and he was moving, somewhat unwittingly, toward the conclusion that would become the core definition of his landmark work, An American Dilemma: that Americans, for all their differences, for all their warring and rivalries, were bound by a distinct “American creed,” a common set of values that embodied such concepts as fair play and an equal chance for everyone. He was coming to that view in the unlikeliest of settings. He had been able to sit with the rapaciously racist U.S. senator from Mississippi Theodore Bilbo, listen to his proposal for shipping Negroes back to Africa, ask why he hadn’t proposed instead that they be sterilized, and come away uplifted by Bilbo’s answer. “American opinion would never allow it,” Bilbo had told him. “It goes against all our ideals and the sentiments of the people.”3

But for all his excitement, information, and knowledge, Myrdal remained mystified. How had the South’s certifiable, pathological inhumanity toward Negroes been allowed to exist for so long into the twentieth century? Why didn’t anyone outside the South know? If they did know, why didn’t they do something about it? Who could do something about it? Who would? Where would the leadership for change come from?

Myrdal returned to the United States and his racial study in 1941, brimming with the insights he would need for An American Dilemma to have an impact on the country.4 Seeing his homeland’s willingness to trade freedoms for security of another kind, Myrdal came to appreciate the vital role the American press could play in challenging the status quo of race relations.

In Sweden, newspapers wanted to report the news but were blocked by the government. In America, the First Amendment kept the government in check, but the press, other than black newspapers and a handful of liberal southern editors, simply didn’t recognize racism in America as a story. The segregation of the Negro in America, by law in the South and by neighborhood and social and economic stratification in the North, had engulfed the press as well as America’s citizens. The mainstream American press wrote about whites but seldom about Negro Americans or discrimination against them; that was left to the Negro press.

Myrdal had a clear understanding of the Negro press’s role in fostering positive discontent. He saw the essential leadership role that southern moderate and liberal white editors were playing by speaking out against institutionalized race discrimination, yet he was aware of the anguish they felt as the pressure to conform intensified. There was also the segregationist press in the South that dehumanized Negroes in print and suppressed the biggest story in their midst. And he came to see the northern press—and the national press, such as it was—as the best hope for force-feeding the rest of the nation a diet so loaded with stories about the cruelty of racism that it would have to rise up in protest.

“The Northerner does not have his social conscience and all his political thinking permeated with the Negro problem as the Southerner does,” Myrdal wrote in the second chapter of An American Dilemma. “Rather, he succeeds in forgetting about it most of the time. The Northern newspapers help him by minimizing all Negro news, except crime news. The Northerners want to hear as little as possible about the Negroes, both in the South and in the North, and they have, of course, good reasons for that.

“The result is an astonishing ignorance about the Negro on the part of the white public in the North. White Southerners, too, are ignorant of many phases of the Negro’s life, but their ignorance has not such a simple and unemotional character as that in the North. There are many educated Northerners who are well informed about foreign problems but almost absolutely ignorant about Negro conditions both in their own city and in the nation as a whole.”5

Left to their own devices, white people in America would want to keep it that way, Myrdal wrote. They’d prefer to be able to accept the stereotype that Negroes “are criminal and of disgustingly, but somewhat enticingly, loose sexual morals; that they are religious and have a gift for dancing and singing; and that they are the happy-go- lucky children of nature who get a kick out of life which white people are too civilized to get.”6

Myrdal concluded that there was one barrier between the white northerner’s ignorance and his sense of outrage that the creed was being poisoned. That barrier was knowledge, incontrovertible information that was strong enough, graphic enough, and constant enough to overcome “the opportunistic desire of the whites for ignorance.”

“A great many Northerners, perhaps the majority, get shocked and shaken in their conscience when they learn the facts,” Myrdal wrote. “The average Northerner does not understand the reality and the effects of such discriminations as those in which he himself is taking part in his routine of life.”

Then, underscoring his point in italics, Myrdal reached the conclusion that would prove to be uncannily prescient. Even before he got to the fiftieth page of his tome, he wrote, “To get publicity is of the highest strategic importance to the Negro people.”

He added, “There is no doubt, in the writer’s opinion, that a great majority of white people in America would be prepared to give the Negro a substantially better deal if they knew the facts.”7

The future of race relations, Myrdal believed, rested largely in the hands of the American press.

An American Dilemma was both a portrait of segregation and a mirror in which an emerging generation of southerners would measure themselves. In a few short years, the book would have a personal impact on a core group of journalists, judges, lawyers, and academicians, who, in turn, would exercise influence on race relations in the South over the next two decades. The book would become a cornerstone of the Supreme Court’s landmark verdict against school segregation a full decade later, and it would become a touchstone by which progressive journalists, both southern and northern, would measure how far the South had come, how far it had to go, and the extent of their roles and responsibilities.

The Myrdal investigation was so incisive and comprehensive—monumental, even—that it would for many years remain a mandatory starting point for anyone seriously studying race in the United States. Its timing was perfect. Most of its fieldwork occurred in the three years before the United States entered World War II, a period in which segregation in the South was as rigid as it ever got. The book ran 1,483 pages long yet was a distillation of a raw product that included 44 monographs totaling 15,000 pages.8

More remarkable than the study’s impact was its foresight. The coming years would prove, time and again, the extraordinary connection between news coverage of race discrimination—publicity, as Myrdal called it—and the emerging protest against discrimination—the civil rights movement, as it became known. That movement grew to be the most dynamic American news story of the last half of the twentieth century.

At no other time in U.S. history were the news media—another phrase that did not exist at the time—more influential than they were in the 1950s and 1960s, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. From the news coverage came significant and enduring changes not only in the civil rights movement but also in the way the print and television media did their jobs. There is little in American society that was not altered by the civil rights movement. There is little in the civil rights movement that was not changed by the news coverage of it. And there is little in the way the news media operate that was not influenced by their coverage of the movement.

An American Dilemma began with a decision by the Carnegie Corporation to conduct a comprehensive study of race in America, and especially of segregation and white supremacy in the South. Recalling the contribution of Alexis de Tocqueville, a Frenchman, in his book Democracy in America, the foundation decided its racial study should be headed by a non-American scholar from a country with no history of colonialism or racial domination.

In the beginning, Myrdal declined the Carnegie offer. He was, after all, a member of the House of the Swedish Parliament, the rough equivalent of the U.S. Senate. He was also a director of the national bank at a moment when Sweden was hobbled by economic depression. He would have to resign both positions and take leave from a prestigious chair in economics at the University of Stockholm, where he was considered one of the nation’s most brilliant academics. What’s more, the Myrdals had recently found an ideological home and leadership positions in the reform policies of the Social Democratic Party, which favored social engineering and economic planning.

He was fluent in English and no stranger to the United States. He and Alva, a psychologist, had been fellows in the Rockefeller Foundation’s social science program in 1929–30. He had refused the Rockefeller Foundation traveling fellowship for himself until the foundation agreed to make Alva a fellow as well.9 No one at the foundation had reason to regret the deal. Indeed, officials of the Rockefeller Foundation regarded Gunnar Myrdal as one of the program’s great successes and recommended him with enthusiasm to Frederick P. Keppel, president of the Carnegie Corporation.

After saying no, Myrdal changed his mind, but only on the condition that he have complete control over planning the study. The foundation agreed. Myrdal became enthusiastic. “I shall work on the Negro—I will do nothing else,” he wrote. “I shall think and dream of the Negro 24 hours a day. . . .”10

He began work in September 1938, almost immediately on his arrival, and plunged into it with confidence; he viewed himself as “born abnormally curious” and specially suited to the investigation of a complicated social problem.11

On his first field trip, Myrdal was accompanied by his primary researcher and writer, Ralph Bunche, a UCLA- and Harvard-educated Negro whose urbane presence was more jarring than Myrdal’s in some parts of the South. Myrdal was stunned by what he saw. Though prepared for the worst, the Swedish economist had not anticipated anything like this. “I didn’t realize,” he promptly wrote his sponsor, Keppel, “what a terrible problem you have put me into. I mean we are horrified.”12

To get an understanding of segregation, the talkative Myrdal and his team moved through the southern states, absorbing experiences, data, impressions, previous studies, and viewpoints.13 The South they discovered was but a single lifetime, fifty-six years, removed from the end of Reconstruction.

As an economist, he was staggered by the material plight of Negroes. It was so grindingly desperate that only one word seemed to describe it: pathological. For southern Negroes, poverty had become a disease of epidemic proportions. “Except for a small minority enjoying upper or middle class status, the masses of American Negroes, in the rural south and in the segregated slum quarters in southern cities, are destitute,” Myrdal wrote. “They own little property; even their household goods are mostly inadequate and dilapidated. Their incomes are not only low but irregular. They thus live day to day and have scant security for the future.”14

From the Hardcover edition.

An American Dilemma:

“An Astonishing Ignorance . . .”

The winter of 1940 was a cruel one for Gunnar Myrdal, and spring was shaping up even worse. He was in the United States, finishing the research on the most comprehensive study yet of race relations and the condition of Negroes in America. But he was having trouble reaching conclusions, and he struggled to outline and conceptualize the writing. “The whole plan is now in danger of breaking down,” he wrote the Carnegie Foundation, which was underwriting his project.

What’s more, the gathering crisis in Europe had thrown him into a depression; he feared for the very existence of his native Sweden. In April, Nazi Germany had invaded Denmark and Norway. Myrdal believed Sweden would be next. He put aside more than two years of work by 125 researchers and began arranging passage home for himself, his wife, Alva, and their three children. He and Alva wanted to fight alongside their countrymen if the worst should come. The boat he found, the Mathilda Thorden, a Finnish freighter, was laden with explosives, and the captain tried to dissuade the Myrdals from boarding the dangerous ship. When this failed, the captain jokingly urged Myrdal to look on the bright side. He would not have to worry about his family freezing to death in icy waters. If German U-boats attacked, the resulting explosion would almost certainly kill everyone instantly.

The U-boats did not attack, and the Myrdals arrived in Sweden only to be appalled by what was happening there. Rather than preparing for war with Germany, the Swedish government was seeking an accommodation with the Nazis.

Knowing that Germany was monitoring the Swedish press for anti-German sentiment, the government first confiscated copies of anti-Nazi newspapers; then, emboldened, it interfered with the distribution of one of the nation’s most important dailies, Göteborgs Handelstidning. This, Myrdal believed, could not happen in America. He was outraged. “The press is strangled,” he wrote to a Swedish friend in the United States. “Nothing gets written about Germany. News is suppressed.”1

There and then, Myrdal’s understanding of America and its race relations became crystallized. In a book that quickly took precedence over his Carnegie project, then became its seed, Gunnar and Alva Myrdal wrote Kontakt med Amerika (Contact with America), which was crafted largely to rally Swedish resistance against Hitler. In Kontakt, published in 1941, the Myrdals argued that Swedes had much to learn from America about democracy, dialogue, and self-criticism. “The secret,” they wrote, “is that America, ahead of every other country in the whole Western world, large or small, has a living system of expressed ideals for human cooperation which is unified, stable and clearly formulated.”2 The Carnegie project, they added, was evidence of America’s willingness to sanction a sweeping examination and discussion of a national problem.

Almost all of America’s citizens, the Myrdals said, believed in free speech and a free press. Americans respected other viewpoints even when they strongly disagreed. As a result, diverse ethnic groups were living with one another in peace while Europe was tearing itself apart.

Before writing Kontakt, Myrdal didn’t have the insight or context he needed for his weightier book on race in America. Nor did he have the words he felt would serve as the road map to change. Three years earlier, in 1938, he had reached the South, the dark side of the moon. There, he had found an enigmatic, sometimes exotic, always deeply divided and repressive society whose behavior was known to, but overlooked by, the world beyond. In pursuit of an understanding and insight that was still beyond his grasp, his immersion had been total, the details of his discoveries had been staggering, and he had come to a point where he was no longer horrified by the pathology of racism or stunned by the cruelty and pervasiveness of discrimination. He had found himself fascinated by the way an entire social order had been built, and rationalized, around race.

By early 1940, Myrdal frequently found himself feeling oddly optimistic about attitudes he found despicable, and he was moving, somewhat unwittingly, toward the conclusion that would become the core definition of his landmark work, An American Dilemma: that Americans, for all their differences, for all their warring and rivalries, were bound by a distinct “American creed,” a common set of values that embodied such concepts as fair play and an equal chance for everyone. He was coming to that view in the unlikeliest of settings. He had been able to sit with the rapaciously racist U.S. senator from Mississippi Theodore Bilbo, listen to his proposal for shipping Negroes back to Africa, ask why he hadn’t proposed instead that they be sterilized, and come away uplifted by Bilbo’s answer. “American opinion would never allow it,” Bilbo had told him. “It goes against all our ideals and the sentiments of the people.”3

But for all his excitement, information, and knowledge, Myrdal remained mystified. How had the South’s certifiable, pathological inhumanity toward Negroes been allowed to exist for so long into the twentieth century? Why didn’t anyone outside the South know? If they did know, why didn’t they do something about it? Who could do something about it? Who would? Where would the leadership for change come from?

Myrdal returned to the United States and his racial study in 1941, brimming with the insights he would need for An American Dilemma to have an impact on the country.4 Seeing his homeland’s willingness to trade freedoms for security of another kind, Myrdal came to appreciate the vital role the American press could play in challenging the status quo of race relations.

In Sweden, newspapers wanted to report the news but were blocked by the government. In America, the First Amendment kept the government in check, but the press, other than black newspapers and a handful of liberal southern editors, simply didn’t recognize racism in America as a story. The segregation of the Negro in America, by law in the South and by neighborhood and social and economic stratification in the North, had engulfed the press as well as America’s citizens. The mainstream American press wrote about whites but seldom about Negro Americans or discrimination against them; that was left to the Negro press.

Myrdal had a clear understanding of the Negro press’s role in fostering positive discontent. He saw the essential leadership role that southern moderate and liberal white editors were playing by speaking out against institutionalized race discrimination, yet he was aware of the anguish they felt as the pressure to conform intensified. There was also the segregationist press in the South that dehumanized Negroes in print and suppressed the biggest story in their midst. And he came to see the northern press—and the national press, such as it was—as the best hope for force-feeding the rest of the nation a diet so loaded with stories about the cruelty of racism that it would have to rise up in protest.

“The Northerner does not have his social conscience and all his political thinking permeated with the Negro problem as the Southerner does,” Myrdal wrote in the second chapter of An American Dilemma. “Rather, he succeeds in forgetting about it most of the time. The Northern newspapers help him by minimizing all Negro news, except crime news. The Northerners want to hear as little as possible about the Negroes, both in the South and in the North, and they have, of course, good reasons for that.

“The result is an astonishing ignorance about the Negro on the part of the white public in the North. White Southerners, too, are ignorant of many phases of the Negro’s life, but their ignorance has not such a simple and unemotional character as that in the North. There are many educated Northerners who are well informed about foreign problems but almost absolutely ignorant about Negro conditions both in their own city and in the nation as a whole.”5

Left to their own devices, white people in America would want to keep it that way, Myrdal wrote. They’d prefer to be able to accept the stereotype that Negroes “are criminal and of disgustingly, but somewhat enticingly, loose sexual morals; that they are religious and have a gift for dancing and singing; and that they are the happy-go- lucky children of nature who get a kick out of life which white people are too civilized to get.”6

Myrdal concluded that there was one barrier between the white northerner’s ignorance and his sense of outrage that the creed was being poisoned. That barrier was knowledge, incontrovertible information that was strong enough, graphic enough, and constant enough to overcome “the opportunistic desire of the whites for ignorance.”

“A great many Northerners, perhaps the majority, get shocked and shaken in their conscience when they learn the facts,” Myrdal wrote. “The average Northerner does not understand the reality and the effects of such discriminations as those in which he himself is taking part in his routine of life.”

Then, underscoring his point in italics, Myrdal reached the conclusion that would prove to be uncannily prescient. Even before he got to the fiftieth page of his tome, he wrote, “To get publicity is of the highest strategic importance to the Negro people.”

He added, “There is no doubt, in the writer’s opinion, that a great majority of white people in America would be prepared to give the Negro a substantially better deal if they knew the facts.”7

The future of race relations, Myrdal believed, rested largely in the hands of the American press.

An American Dilemma was both a portrait of segregation and a mirror in which an emerging generation of southerners would measure themselves. In a few short years, the book would have a personal impact on a core group of journalists, judges, lawyers, and academicians, who, in turn, would exercise influence on race relations in the South over the next two decades. The book would become a cornerstone of the Supreme Court’s landmark verdict against school segregation a full decade later, and it would become a touchstone by which progressive journalists, both southern and northern, would measure how far the South had come, how far it had to go, and the extent of their roles and responsibilities.

The Myrdal investigation was so incisive and comprehensive—monumental, even—that it would for many years remain a mandatory starting point for anyone seriously studying race in the United States. Its timing was perfect. Most of its fieldwork occurred in the three years before the United States entered World War II, a period in which segregation in the South was as rigid as it ever got. The book ran 1,483 pages long yet was a distillation of a raw product that included 44 monographs totaling 15,000 pages.8

More remarkable than the study’s impact was its foresight. The coming years would prove, time and again, the extraordinary connection between news coverage of race discrimination—publicity, as Myrdal called it—and the emerging protest against discrimination—the civil rights movement, as it became known. That movement grew to be the most dynamic American news story of the last half of the twentieth century.

At no other time in U.S. history were the news media—another phrase that did not exist at the time—more influential than they were in the 1950s and 1960s, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. From the news coverage came significant and enduring changes not only in the civil rights movement but also in the way the print and television media did their jobs. There is little in American society that was not altered by the civil rights movement. There is little in the civil rights movement that was not changed by the news coverage of it. And there is little in the way the news media operate that was not influenced by their coverage of the movement.

An American Dilemma began with a decision by the Carnegie Corporation to conduct a comprehensive study of race in America, and especially of segregation and white supremacy in the South. Recalling the contribution of Alexis de Tocqueville, a Frenchman, in his book Democracy in America, the foundation decided its racial study should be headed by a non-American scholar from a country with no history of colonialism or racial domination.

In the beginning, Myrdal declined the Carnegie offer. He was, after all, a member of the House of the Swedish Parliament, the rough equivalent of the U.S. Senate. He was also a director of the national bank at a moment when Sweden was hobbled by economic depression. He would have to resign both positions and take leave from a prestigious chair in economics at the University of Stockholm, where he was considered one of the nation’s most brilliant academics. What’s more, the Myrdals had recently found an ideological home and leadership positions in the reform policies of the Social Democratic Party, which favored social engineering and economic planning.

He was fluent in English and no stranger to the United States. He and Alva, a psychologist, had been fellows in the Rockefeller Foundation’s social science program in 1929–30. He had refused the Rockefeller Foundation traveling fellowship for himself until the foundation agreed to make Alva a fellow as well.9 No one at the foundation had reason to regret the deal. Indeed, officials of the Rockefeller Foundation regarded Gunnar Myrdal as one of the program’s great successes and recommended him with enthusiasm to Frederick P. Keppel, president of the Carnegie Corporation.

After saying no, Myrdal changed his mind, but only on the condition that he have complete control over planning the study. The foundation agreed. Myrdal became enthusiastic. “I shall work on the Negro—I will do nothing else,” he wrote. “I shall think and dream of the Negro 24 hours a day. . . .”10

He began work in September 1938, almost immediately on his arrival, and plunged into it with confidence; he viewed himself as “born abnormally curious” and specially suited to the investigation of a complicated social problem.11

On his first field trip, Myrdal was accompanied by his primary researcher and writer, Ralph Bunche, a UCLA- and Harvard-educated Negro whose urbane presence was more jarring than Myrdal’s in some parts of the South. Myrdal was stunned by what he saw. Though prepared for the worst, the Swedish economist had not anticipated anything like this. “I didn’t realize,” he promptly wrote his sponsor, Keppel, “what a terrible problem you have put me into. I mean we are horrified.”12

To get an understanding of segregation, the talkative Myrdal and his team moved through the southern states, absorbing experiences, data, impressions, previous studies, and viewpoints.13 The South they discovered was but a single lifetime, fifty-six years, removed from the end of Reconstruction.

As an economist, he was staggered by the material plight of Negroes. It was so grindingly desperate that only one word seemed to describe it: pathological. For southern Negroes, poverty had become a disease of epidemic proportions. “Except for a small minority enjoying upper or middle class status, the masses of American Negroes, in the rural south and in the segregated slum quarters in southern cities, are destitute,” Myrdal wrote. “They own little property; even their household goods are mostly inadequate and dilapidated. Their incomes are not only low but irregular. They thus live day to day and have scant security for the future.”14

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

This gripping account of how America and the world found out about the Civil Rights movement is written by two veteran journalists of the "race beat" from 1954 to 1965. Building on an exhaustive base of interviews, oral histories, and news stories, the authors provide a fresh account of the events.

Premii

- Pulitzer Prize Winner, 2007