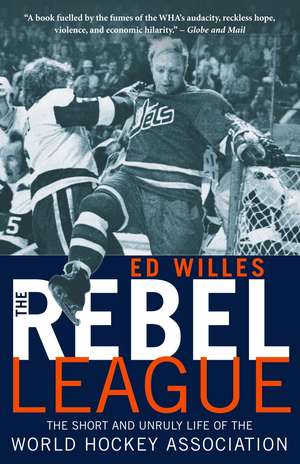

The Rebel League: The Short and Unruly Life of the World Hockey Association

Autor Ed Willesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2005

The Rebel League celebrates the good, the bad, and the ugly of the fabled WHA. It is filled with hilarious anecdotes, behind the scenes dealing, and simply great hockey. It tells the story of Bobby Hull’s astonishing million-dollar signing, which helped launch the league, and how he lost his toupee in an on-ice scrap.It explains how a team of naked Birmingham Bulls ended up in an arena concourse spoiling for a brawl. How the Oilers had to smuggle fugitive forward Frankie “Seldom” Beaton out of their dressing room in an equipment bag. And how Mark Howe sometimes forgot not to yell “Dad!” when he called for his teammate father, Gordie, to pass. There’s the making of Slap Shot, that classic of modern cinema, and the making of the virtuoso line of Hull, Anders Hedberg, and Ulf Nilsson.

It began as the moneymaking scheme of two California lawyers. They didn’t know much about hockey, but they sure knew how to shake things up. The upstart WHA introduced to the world 27 new hockey franchises, a trail of bounced cheques, fractious lawsuits, and folded teams. It introduced the crackpots, goons, and crazies that are so well remembered as the league’s bizarre legacy.

But the hit-and-miss league was much more than a travelling circus of the weird and wonderful. It was the vanguard that drove hockey into the modern age. It ended the NHL’s monopoly, freed players from the reserve clause, ushered in the 18-year-old draft, moved the game into the Sun Belt, and put European players on the ice in numbers previously unimagined.

The rebel league of the WHA gave shining stars their big-league debut and others their swan song, and provided high-octane fuel for some spectacular flameouts. By the end of its seven years, there were just six teams left standing, four of which – the Winnipeg Jets, Quebec Nordiques, Edmonton Oilers, and Hartford Whalers – would wind up in the expanded NHL.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 104.01 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 156

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.90€ • 21.69$ • 16.77£

19.90€ • 21.69$ • 16.77£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Livrare express 19-25 martie pentru 25.89 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771089497

ISBN-10: 077108949X

Pagini: 277

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 077108949X

Pagini: 277

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

ED WILLES started his journalism career in 1982 at the Medicine Hat News, which is where the idea for this book was born. After four years there he moved on to the Regina Leader-Post, then to the Winnipeg Sun, where he was the hockey writer for eight years. From 1997 to 1998, he worked as a freelancer in Montreal and ended up writing for the New York Times. That summer he was offered the sports columnist job at The Province (Vancouver), where he stayed until his retirement in 2020. He is the author of Gretzky to Lemieux: The Story of the 1987 Canada Cup and The Rebel League: The Short and Unruly Life of the World Hockey Association. He lives in North Vancouver, B.C., with his wife and two children.

Extras

He probably didn’t think it would be an issue when he joined the WHA, but in addition to his many other personality quirks Mike Walton was deathly afraid of spiders, cockroaches, and anything else that crawled and had six or more legs. Sadly, this phobia qualified as something of an occupational hazard for Shaky, because the new league, in the early years at least, played in places that did not discourage the presence of insects.

The Sam Houston Arena, for instance, built in 1937 and famous for its Friday-night wrestling cards, was fairly typical of the first generation of WHA rinks. Owner Paul Deneau invested enough money to bring it up to code and even installed Plexiglas in place of the chicken wire that was still in use in many of the old rinks. “I thought it was okay,” says Dineen.

Still, no one was mistaking it for Madison Square Garden.

“We used to have cockroach contests in the dressing room,” says John Garrett. “We’d be putting our equipment on, and a cockroach always got in your skates or your sweater. If you got a really big one, you’d hang it from a skate lace in the middle of the dressing room. Then the other guys would try to get a bigger one. There was no money involved. We just did it for the honour.”

Which was funny to everyone except Walton. During one road trip, the Saints played in Houston before taking off immediately for Baltimore. The accepted WHA procedure after a game in Houston was to shake your equipment vigorously to dislodge any unwanted guests, who could, if left unattended, multiply and eat your brain. Walton, sadly, forgot this safety precaution, which caused some excitement when he took his skates out of his bag in Baltimore.

“I was in the coaches’ room and I heard this horrible scream coming from the dressing room,” says Harry Neale. “I thought, Oh my god, someone’s cut their hand off. Then I see this cockroach coming out of our dressing room and I figured out what had happened.

“I think the cockroach made the rest of the road trip with us and he didn’t ask for a per diem so we kept him around.”

The pioneers of the new league would experience many such indignities in the WHA’s sevenyear existence. While they were grateful for the opportunity, to say nothing of the paycheques, NHL veterans who’d lived the life in The Show would often look at their surroundings and ask the great existential question, “Just what the hell am I doing here?”

Some of them never received a satisfactory answer. But the journeymen and minor-leaguers endured the league’s more unusual aspects with patience and humour, because they knew the WHA was infinitely superior to the alternative.

“I wasn’t like Keon, McKenzie, or Walton,” says Dave Hanson. “I had nothing to compare it to. I just thought this was the way things were, and it was a great adventure. We had a lot of fun.”

One of the WHA’s biggest sources of amusement was its buildings. In time, the rebels could boast a series of new arenas that were years ahead of the NHL’s and foreshadowed the great steel-andglass mausoleums of today. There was the new St. Paul Civic Center. The Oilers moved into Northlands Coliseum midway through Year 3. The Indianapolis Racers played in the magnificent new Market Square Arena. Nick Mileti would build a new facility for the Cleveland Crusaders in Richfield that, at the time, was the most luxurious in hockey. Cincinnati and New England would also move into new buildings. But over the first couple of years, the league was jammed into a collection of dusty old pre-war rinks that, while not without their own charms, fell somewhat short of big-league.

“You just saw things in the WHA you never saw anywhere else,” says Paul Shmyr.

And Shmyr knows whereof he speaks. The defenceman played in all seven years of the WHA, his first four in Cleveland as the Crusaders’ captain. In his first two seasons, the Crusaders played out of the old Cleveland Arena in an area of town that was scarier than Nightmare on Elm Street. Five Crusaders had their cars stolen out of the parking lot at the Arena, and two of them, Wayne Muloin and Tom Edur, lost new Thunderbirds on the same night. Steve Thomas, the Crusaders’ trainer, was mugged three times one winter. A would-be thief demanded Thomas’s watch. “They got that last week,” Thomas answered.

“It was a war zone,” says Shmyr. “You didn’t take your helmet off going from your car to the rink for practice.”

“If you didn’t get mugged during that first year, they didn’t think that much of you,” says Gerry Cheevers, the Crusaders’ goalie.

Inside, it wasn’t much better. Like a number of the old WHA rinks, the Cleveland Arena featured chicken wire instead of Plexiglas. As every WHA player knew, chicken wire had two distinct disadvantages: (1) You could pour beer through it, and (2) it produced some very strange bounces.

“There were two standard lines when you were getting beer dumped on you,” Shmyr says. “The first one was, ‘If you’re going to pour beer on me at least hit me in the mouth.’ The second one was, ‘Hey, that isn’t my brand.’”

But the wire also gave the Crusaders a clear homeice advantage. Neale says when you played there only a couple of times a year, fundamentals such as dump-ins and hardarounds became a complete mystery to the visiting team. The savvy Cheevers, meanwhile, became a master at reading dumpins off the mesh.

“It was like watching Yastrzemski play the Green Monster at Fenway,” Garrett says of Cheevers.

“There wasn’t much to it,” Cheevers shrugs. “When the puck hit the screen, it would just drop.”

At the other end of the ice, the Crusaders’ Gary Jarrett was equally adept at reading the caroms and ricochets in the offensive zone. Jarrett recorded 40 goals and 79 points in the Crusaders’ first year and 31 goals and 70 points in Year 2. However, when the Crusaders moved to their splendid new home in Richfield, and away from the chicken wire, Jarrett’s totals fell to 41, then 33 points, and he retired after Year 4.

Jarrett, mind you, was probably the only player sad to see the Crusaders move in Year 3 into their new $20-million palace in the Cleveland suburbs. Widely described as the finest indoor facility in North America, the Coliseum had a seating capacity of just under twenty thousand, private boxes, a Jumbotron, and a fancy-schmancy restaurant long before those amenities were the industry norms.

“It was the nicest rink by far in all of hockey, and it compares to anything they’ve built today,” says Shmyr.

There were, however, a few problems. The roads into the Coliseum, for starters, were unable to handle the traffic it created. Opening night featured a Frank Sinatra concert and a massive traffic jam in which ticket holders, dressed in tuxes and formal gowns, simply abandoned their cars on the highway miles away and hiked to the Coliseum in their evening wear.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Sam Houston Arena, for instance, built in 1937 and famous for its Friday-night wrestling cards, was fairly typical of the first generation of WHA rinks. Owner Paul Deneau invested enough money to bring it up to code and even installed Plexiglas in place of the chicken wire that was still in use in many of the old rinks. “I thought it was okay,” says Dineen.

Still, no one was mistaking it for Madison Square Garden.

“We used to have cockroach contests in the dressing room,” says John Garrett. “We’d be putting our equipment on, and a cockroach always got in your skates or your sweater. If you got a really big one, you’d hang it from a skate lace in the middle of the dressing room. Then the other guys would try to get a bigger one. There was no money involved. We just did it for the honour.”

Which was funny to everyone except Walton. During one road trip, the Saints played in Houston before taking off immediately for Baltimore. The accepted WHA procedure after a game in Houston was to shake your equipment vigorously to dislodge any unwanted guests, who could, if left unattended, multiply and eat your brain. Walton, sadly, forgot this safety precaution, which caused some excitement when he took his skates out of his bag in Baltimore.

“I was in the coaches’ room and I heard this horrible scream coming from the dressing room,” says Harry Neale. “I thought, Oh my god, someone’s cut their hand off. Then I see this cockroach coming out of our dressing room and I figured out what had happened.

“I think the cockroach made the rest of the road trip with us and he didn’t ask for a per diem so we kept him around.”

The pioneers of the new league would experience many such indignities in the WHA’s sevenyear existence. While they were grateful for the opportunity, to say nothing of the paycheques, NHL veterans who’d lived the life in The Show would often look at their surroundings and ask the great existential question, “Just what the hell am I doing here?”

Some of them never received a satisfactory answer. But the journeymen and minor-leaguers endured the league’s more unusual aspects with patience and humour, because they knew the WHA was infinitely superior to the alternative.

“I wasn’t like Keon, McKenzie, or Walton,” says Dave Hanson. “I had nothing to compare it to. I just thought this was the way things were, and it was a great adventure. We had a lot of fun.”

One of the WHA’s biggest sources of amusement was its buildings. In time, the rebels could boast a series of new arenas that were years ahead of the NHL’s and foreshadowed the great steel-andglass mausoleums of today. There was the new St. Paul Civic Center. The Oilers moved into Northlands Coliseum midway through Year 3. The Indianapolis Racers played in the magnificent new Market Square Arena. Nick Mileti would build a new facility for the Cleveland Crusaders in Richfield that, at the time, was the most luxurious in hockey. Cincinnati and New England would also move into new buildings. But over the first couple of years, the league was jammed into a collection of dusty old pre-war rinks that, while not without their own charms, fell somewhat short of big-league.

“You just saw things in the WHA you never saw anywhere else,” says Paul Shmyr.

And Shmyr knows whereof he speaks. The defenceman played in all seven years of the WHA, his first four in Cleveland as the Crusaders’ captain. In his first two seasons, the Crusaders played out of the old Cleveland Arena in an area of town that was scarier than Nightmare on Elm Street. Five Crusaders had their cars stolen out of the parking lot at the Arena, and two of them, Wayne Muloin and Tom Edur, lost new Thunderbirds on the same night. Steve Thomas, the Crusaders’ trainer, was mugged three times one winter. A would-be thief demanded Thomas’s watch. “They got that last week,” Thomas answered.

“It was a war zone,” says Shmyr. “You didn’t take your helmet off going from your car to the rink for practice.”

“If you didn’t get mugged during that first year, they didn’t think that much of you,” says Gerry Cheevers, the Crusaders’ goalie.

Inside, it wasn’t much better. Like a number of the old WHA rinks, the Cleveland Arena featured chicken wire instead of Plexiglas. As every WHA player knew, chicken wire had two distinct disadvantages: (1) You could pour beer through it, and (2) it produced some very strange bounces.

“There were two standard lines when you were getting beer dumped on you,” Shmyr says. “The first one was, ‘If you’re going to pour beer on me at least hit me in the mouth.’ The second one was, ‘Hey, that isn’t my brand.’”

But the wire also gave the Crusaders a clear homeice advantage. Neale says when you played there only a couple of times a year, fundamentals such as dump-ins and hardarounds became a complete mystery to the visiting team. The savvy Cheevers, meanwhile, became a master at reading dumpins off the mesh.

“It was like watching Yastrzemski play the Green Monster at Fenway,” Garrett says of Cheevers.

“There wasn’t much to it,” Cheevers shrugs. “When the puck hit the screen, it would just drop.”

At the other end of the ice, the Crusaders’ Gary Jarrett was equally adept at reading the caroms and ricochets in the offensive zone. Jarrett recorded 40 goals and 79 points in the Crusaders’ first year and 31 goals and 70 points in Year 2. However, when the Crusaders moved to their splendid new home in Richfield, and away from the chicken wire, Jarrett’s totals fell to 41, then 33 points, and he retired after Year 4.

Jarrett, mind you, was probably the only player sad to see the Crusaders move in Year 3 into their new $20-million palace in the Cleveland suburbs. Widely described as the finest indoor facility in North America, the Coliseum had a seating capacity of just under twenty thousand, private boxes, a Jumbotron, and a fancy-schmancy restaurant long before those amenities were the industry norms.

“It was the nicest rink by far in all of hockey, and it compares to anything they’ve built today,” says Shmyr.

There were, however, a few problems. The roads into the Coliseum, for starters, were unable to handle the traffic it created. Opening night featured a Frank Sinatra concert and a massive traffic jam in which ticket holders, dressed in tuxes and formal gowns, simply abandoned their cars on the highway miles away and hiked to the Coliseum in their evening wear.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A must-read for hockey fans.”

—Canadian Press

“A book fuelled by the fumes of the WHA’s audacity, reckless hope, violence, and economic hilarity. . . . A highly entertaining tale.”

—Globe and Mail

—Canadian Press

“A book fuelled by the fumes of the WHA’s audacity, reckless hope, violence, and economic hilarity. . . . A highly entertaining tale.”

—Globe and Mail