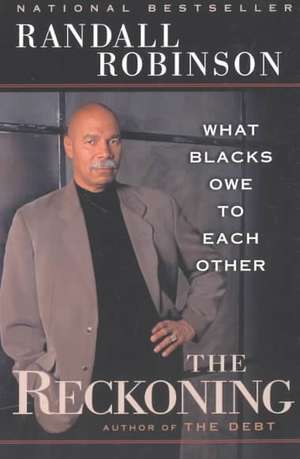

The Reckoning

Autor Randall Robinsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2002

In The Reckoning, Randall Robinson examines the crime and poverty that grips much of urban America and urges black Americans to speak out and reach back to ensure their social and economic success in this country. With insight, compassion, and unflinching honesty, Robinson explores the twin blights of crime and poverty—the former often a symptom of the latter—and asks questions that are critical to the rebuilding of black communities: How do we create awareness of the heroic efforts already being made and how can we bring our troubled youth to safety? A product of Robinson’s work with gang members, ex-convicts, and others who have been scarred by the harshness of life in our inner cities, The Reckoning is certain to be as important and controversial as his earlier books.

Preț: 133.21 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.49€ • 26.68$ • 21.09£

25.49€ • 26.68$ • 21.09£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780452283145

ISBN-10: 0452283140

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

ISBN-10: 0452283140

Pagini: 306

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

Cuprins

The Reckoning Introduction

1. The Luncheon

2. My Thoughts As Peewee Waits to Speak

3. Peewee's Speach

4. Deja Vu

5. Playing the Hand You Are Dealt

6. Peewee's Revenge

7. The Aspiring American Entrepreneur

8. Peewee's Father

9. Wadleigh Junior High School

10. Peewee and the White Stockbroker

11. Wealth, Privilege, Social Class, and Race

12. Washington, D.C., in the Year 2076

13. New York, 1964

14. False Exits

15. Peewee Goes to Prison

16. New Child Lynch

17. Walk-up Retail

18. Aubrey Lynch

19. Peewee and New Child: Saving Themselves and Saving Others

Afterword

My Plea

Index

Acknowledgments

1. The Luncheon

2. My Thoughts As Peewee Waits to Speak

3. Peewee's Speach

4. Deja Vu

5. Playing the Hand You Are Dealt

6. Peewee's Revenge

7. The Aspiring American Entrepreneur

8. Peewee's Father

9. Wadleigh Junior High School

10. Peewee and the White Stockbroker

11. Wealth, Privilege, Social Class, and Race

12. Washington, D.C., in the Year 2076

13. New York, 1964

14. False Exits

15. Peewee Goes to Prison

16. New Child Lynch

17. Walk-up Retail

18. Aubrey Lynch

19. Peewee and New Child: Saving Themselves and Saving Others

Afterword

My Plea

Index

Acknowledgments

Recenzii

“Engaging…Robinson continues an important conversation…His anecdotes support his attempts to reclaim African heritage and empower African Americans.” —The Washington Post

“A reality check. The Reckoning makes you stop and think, and inspires you to take action.” —Heart & Soul

“A reality check. The Reckoning makes you stop and think, and inspires you to take action.” —Heart & Soul

Notă biografică

Randall Robinson is the founder and president of TransAfrica, the organization that spearheaded the movement to influence U.S. policies toward international black leadership. He is the author of Defending the Spirit: A Black Life in America, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks and The Reckoning: What Blacks Owe To Each Other. Frequently featured in major print media, he has appeared on Charlie Rose, Today, Good Morning America, and the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, among others.

Extras

The story that is the centerpiece of this book is true. The names of its principal characters, Peewee Kirkland, New Child Lynch, and Mark Lawrence, are real. I have changed the names of others for reasons that will become obvious.

I do not venture in this telling far afield of the events of the lives remarked here. You, no doubt, would have puzzled out the reasons for this narrowness of compass on your own. Sometimes, very old, very broad stories are best told small, in consumable units of observed lives, replete with travail and stunted prospect. Social data, the scholar's tool, serve well enough in conveying the trend and breadth of social conditions. But the usefulness of the academician's bar graph ends there, bleaching from general view the searing pain and hopelessness borne by the modern, uncomprehending victims of old, obscure, and oft-transmuted American social policies. To understand the full damage that America has done to the black world over the last 346 years, we must extrapolate the general from the specific, not the other way around.

The young black men whose stories are told here represent the gravely endangered generation of the fathers of our future. They, like the millions who comprise their peer ranks, were born into the rigged game of dysfunctional families, variably crippling poverty, poor education, and all but nonexistent opportunity for long-term success.

Some of them miraculously survive; a few, even, like Mark Lawrence and Peewee Kirkland, with an abiding exercise of fatherlike duty towards the many like New Child Lynch who are forced to contend with social obstacles that no child in a "civilized" society should ever be compelled to confront.

Such are the legacies for American blacks after 246 years of slavery and the century of government-embraced racial discrimination that followed on slavery's heels. One hundred and thirty-eight years after the Emancipation Proclamation, our young men, slavery's grandsons, are six times more likely to be arrested for a serious crime than are their white counterparts. After arrest, they are more likely than their white counterparts to be prosecuted and convicted. Upon conviction, they serve prison sentences roughly twice as long as those served by whites for the same crimes.

From birth, black inner-city males are strapped onto a hard-life treadmill leading all too often toward early death or jail. While the United States has the highest incarceration rate of any nation in the world, Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, has one of the highest in America. More than one in every three black men in the District of Columbia between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five falls under one or another arm of the criminal justice system.

Prisons, increasingly under private ownership, are a growth industry. Nothing inflates prison stock prices like the growing ranks of American prisoners, the majority of whom are being held for nonviolent crimes and, all too many, in places like Washington, D.C., well past the times set by the courts.

Public funds are being used to subsidize a national private prison industry whose growth depends on higher incarceration rates. Said differently, society is subsidizing its own demise for the benefit of private investors. The investors are disproportionately white. The prisoners are disproportionately black. Inside the new private hells, prisoners toil for private companies, earning but a pittance while undercutting the wages of nonprison labor. Owing to the extremely low wages for prison labor, the companies that employ prisoners constitute, not surprisingly, still another new growth industry. Towards this modern bondage, down this human cattle chute, black males from birth are being herded willy-nilly before our very eyes. It is this new de facto slavery that benefits the same private interests, transmogrified, that its predecessor institution benefited centuries before.

In my last book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks, I argued that only massive American government reparations can begin to repair the devastating economic and psychosocial injury done to blacks in America since 1619 at the hands of, first, the colonial governments, and, later, the American government. But while broad programmatic restitution can insure for African-Americans a future, it cannot salvage a living generation of African-American men and women who are being, in alarming numbers, lost to the black community as wives, husbands, mothers, fathers, breadwinners, and responsible social contributors.

This, we must do for ourselves.

I do not venture in this telling far afield of the events of the lives remarked here. You, no doubt, would have puzzled out the reasons for this narrowness of compass on your own. Sometimes, very old, very broad stories are best told small, in consumable units of observed lives, replete with travail and stunted prospect. Social data, the scholar's tool, serve well enough in conveying the trend and breadth of social conditions. But the usefulness of the academician's bar graph ends there, bleaching from general view the searing pain and hopelessness borne by the modern, uncomprehending victims of old, obscure, and oft-transmuted American social policies. To understand the full damage that America has done to the black world over the last 346 years, we must extrapolate the general from the specific, not the other way around.

The young black men whose stories are told here represent the gravely endangered generation of the fathers of our future. They, like the millions who comprise their peer ranks, were born into the rigged game of dysfunctional families, variably crippling poverty, poor education, and all but nonexistent opportunity for long-term success.

Some of them miraculously survive; a few, even, like Mark Lawrence and Peewee Kirkland, with an abiding exercise of fatherlike duty towards the many like New Child Lynch who are forced to contend with social obstacles that no child in a "civilized" society should ever be compelled to confront.

Such are the legacies for American blacks after 246 years of slavery and the century of government-embraced racial discrimination that followed on slavery's heels. One hundred and thirty-eight years after the Emancipation Proclamation, our young men, slavery's grandsons, are six times more likely to be arrested for a serious crime than are their white counterparts. After arrest, they are more likely than their white counterparts to be prosecuted and convicted. Upon conviction, they serve prison sentences roughly twice as long as those served by whites for the same crimes.

From birth, black inner-city males are strapped onto a hard-life treadmill leading all too often toward early death or jail. While the United States has the highest incarceration rate of any nation in the world, Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, has one of the highest in America. More than one in every three black men in the District of Columbia between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five falls under one or another arm of the criminal justice system.

Prisons, increasingly under private ownership, are a growth industry. Nothing inflates prison stock prices like the growing ranks of American prisoners, the majority of whom are being held for nonviolent crimes and, all too many, in places like Washington, D.C., well past the times set by the courts.

Public funds are being used to subsidize a national private prison industry whose growth depends on higher incarceration rates. Said differently, society is subsidizing its own demise for the benefit of private investors. The investors are disproportionately white. The prisoners are disproportionately black. Inside the new private hells, prisoners toil for private companies, earning but a pittance while undercutting the wages of nonprison labor. Owing to the extremely low wages for prison labor, the companies that employ prisoners constitute, not surprisingly, still another new growth industry. Towards this modern bondage, down this human cattle chute, black males from birth are being herded willy-nilly before our very eyes. It is this new de facto slavery that benefits the same private interests, transmogrified, that its predecessor institution benefited centuries before.

In my last book, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks, I argued that only massive American government reparations can begin to repair the devastating economic and psychosocial injury done to blacks in America since 1619 at the hands of, first, the colonial governments, and, later, the American government. But while broad programmatic restitution can insure for African-Americans a future, it cannot salvage a living generation of African-American men and women who are being, in alarming numbers, lost to the black community as wives, husbands, mothers, fathers, breadwinners, and responsible social contributors.

This, we must do for ourselves.