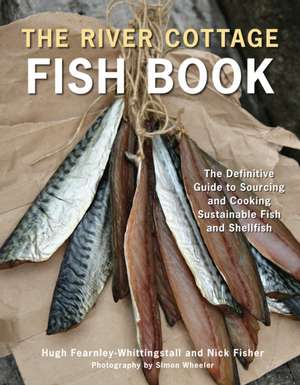

The River Cottage Fish Book: The Definitive Guide to Sourcing and Cooking Sustainable Fish and Shellfish: River Cottage Cookbook

Autor Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, Nick Fisher Fotografii de Simon Wheeleren Limba Engleză Hardback – 29 feb 2012

This ambitious reference-cookbook appeals to both intellect and appetite by focusing on the pleasures of catching, cooking, and eating fish while grounding those actions in a philosophy and practice of sustainability. The authors help us understand the human impact on the seafood population, while their infectious enthusiasm for all manner of fish and shellfish—from the mighty salmon to the humble mackerel to the unsung cockle—inspires us to explore different and unfamiliar species. Fish is superlative food, but it’s also a precious resource. The River Cottage Fish Book delivers a complete education alongside a wealth of recipes, and is the most opinionated and passionate fish book around.

Preț: 341.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 512

Preț estimativ în valută:

65.37€ • 70.99$ • 54.91£

65.37€ • 70.99$ • 54.91£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781607740056

ISBN-10: 1607740052

Pagini: 608

Ilustrații: 433 FULL-COLOR PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 203 x 267 x 45 mm

Greutate: 2.24 kg

Editura: Ten Speed Press

Seria River Cottage Cookbook

ISBN-10: 1607740052

Pagini: 608

Ilustrații: 433 FULL-COLOR PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 203 x 267 x 45 mm

Greutate: 2.24 kg

Editura: Ten Speed Press

Seria River Cottage Cookbook

Notă biografică

HUGH FEARNLEY-WHITTINGSTALL is a renowned British broadcaster, writer, farmer, educator, and campaigner for sustainably produced food. He has written eight books, including The River Cottage Meat Book, the 2008 James Beard Cookbook of the Year. Hugh established the River Cottage farm in rural Dorset, England, in 1998.

NICK FISHER is a leading fish authority and journalist who has created and presented television and radio shows on fishing. He lives in Dorset with his family, a lake full of trout, and several boats.

NICK FISHER is a leading fish authority and journalist who has created and presented television and radio shows on fishing. He lives in Dorset with his family, a lake full of trout, and several boats.

Extras

Introduction

We both love fish. And that is the overriding reason we have written this book. As anglers, cooks, and (very amateur) naturalists, we’ve got fish under our skin. It’s very hard – and rather stressful – to imagine life without them.

Over the years we’ve found all kinds of ways to scratch our fish itch: goldfish in a bowl, visits to aquariums, goggling at Jacques Cousteau on the telly, learning first to snorkel and then to scuba dive. Such enthusiasms have come and gone, but two have always been a constant: catching fish and eating them.

Between us, we have caught and cooked many fish. We have, of course, also caught a fair few that we haven’t cooked, and cooked countless others that we haven’t caught. But we are happiest when these two pursuits collide and we get to consume a fish that we have personally pulled from the deep. For both of us, our passion for fish as quarry and food began at an early age.

Hugh’s first fishing expedition occurred at the age of six, when his dad took him to a stream in Richmond Park, armed with a bamboo cane, a length of string, a bent pin, and a slice of bread. They actually caught a fish! Back home with his Observer’s Book of Fishes, Hugh identified the catch as a mackerel, noting that this was a fish that was meant to live in the sea.

Being omniscient, his dad naturally had a convincing explanation: “Er, it must have decided to swim up from the sea – like a salmon . . .” That was more than good enough for the young Hugh. There was no reason to be suspicious. After all, he had lifted the fish from the stream with his own hands, and watched his father knock it several times on the head with his own eyes.

Hugh’s mum fried the mackerel in butter and served it with a slice of lemon. It was the first fish Hugh had ever eaten that wasn’t finger shaped, coated in bread crumbs, and doused in ketchup – and he enjoyed it very much indeed.

It was ten years before the sorry truth came out. Seeing his teenage son swearing blind to some disbelieving friends that he had once caught a mackerel in a London park with a lump of Mother’s Pride on a bent pin, Hugh’s dad was moved to a guilty confession. He came clean about the trip to the fishmonger’s; the sleight of hand that slipped the fish onto the hook as Hugh was sent behind a bush for a much-needed pee; the ritual dispatch of a fish that had, in fact, already been dead for two days . . .

Hugh was a little disillusioned to discover the deceit but, being sixteen, soon found other things to strop about. In the end he is, of course, eternally grateful to his dad. Grateful to be hooked on fishing, and hooked on fish.

1. Understanding fish

The nitty-gritty of this book is the delightful activity of cooking and eating fish. And we think you’ll derive even more pleasure from your fish and shellfish if you understand a little, or perhaps a lot, about the business of catching and preparing them.

Besides being delicious, fish are uniquely nutritious. So you would think the very least we could do, given their contribution to our well-being, would be to nurture them in return. At this we are failing spectacularly. The prognosis is gloomy on a number of fronts, as the destructive fishing practices of the past half-century have taken their toll. The fact that we can finally acknowledge just how bad things are does offer, paradoxically, a glimmer of hope. We haven’t, thank goodness, passed the point of no return; we still have a stunning range of native fish and shellfish to celebrate. We would both argue that their future lies largely in the hands of the consumer – that’s every single one of us who loves to eat fish.

The angler-cook will, of necessity, prepare much of his or her fish from scratch, and knowing how to wield a filleting knife is clearly essential. But even the landlubber fish enthusiast may once in a while enjoy taking a live crab home or gutting a mackerel at the sink. Our two chapters covering fish and shellfish skills will show you the way.

Four million years ago, an early prototype of the human being, australopithecine man, roamed across the African savannah. He walked upright, stood around 4 feet (1.2m) tall and possessed a brain about the size of a chimp’s. Three million years later, on the verge of extinction, he hadn’t changed much. Despite a few hundred thousand generations of hunting and eating meat, Australopithecus remained pretty much as intellectually and vertically challenged as he had been when he first wandered out onto the plain. He lost the battle for survival – and became just another leaf to have fallen from the evolutionary tree.

Another human forerunner, who overlapped with Australopithecus for the last million years of his time on the planet, was Homo erectus. He grew over 5 feet (1.5m) tall, and in just 200,000 years of evolution he tripled the size of his brain. Equipped with this enlarged gray matter and a range of tools, erectus evolved into sapiens. Hom sap was anatomically modern and technologically minded; in other words, he was us.

Why did one branch of protohumans hit an evolutionary dead end while another grew bigger, stronger, and – crucially – much cleverer? What made one a hopeless, doomed grunter and the other the ancestor of Leonardo da Vinci (plus you and us, of course). The answer is fish.

Homo erectus stood up, but he didn’t stand still. He wandered all over the place, in search of a better living; he left the savannah and reached the coast, where he ate fish, shellfish, and seaweed for the first time (they must have made a nice change from mastodons – so much easier on the teeth). Fossil evidence shows that his burgeoning fish-eating habit coincided with his rapid cerebral growth. Scientists believe this staggering improvement came about because Homo sapiens was nourished by a substance previously present only in trace quantities in his diet: docosahexaenoic acid, or DHA for short. Our bodies aren’t able to manufacture their own DHA, so how did it end up inside them? It must have been something we ate. When it comes to identifying the “superfood” that provided the quantities of DHA necessary for the dramatic expansion of our cranial capacity, the only serious candidate is fish.

DHA is an omega-3 essential fatty acid, of the kind we now know to be vital to brain development. The body converts it into proteins, which it uses specifically to build neurons – the conductors that manage electrochemical activity in the brain. Up to 8 percent of our brain weight is made up of these fatty acids, so to achieve optimal brain growth we need fatty acids in our food. Put simply, the more of them we get, the better our brains develop. And there’s nowhere better

to get them than from fish.

So if it hadn’t been for early man’s trip to the seaside, we might all still be hairy bush dwellers, waiting for someone to invent the wheel (or at least the fish spear). Of course, we should remember that we didn’t become piscivores in order to evolve. We weren’t quite that clever. We ate fish because they were there, they sustained us, and perhaps because we found them delicious. It just so happens that, from a biological and evolutionary perspective, actively choosing to eat something that is so good for you makes for a fantastically virtuous circle. One that has led, down the millennia, to a culture of such stupendous sophistication that books have been written and television shows filmed about our favorite ways of eating fish (among other things).

Fish for health

A fish-rich diet continues to contribute to our well-being. Those cultures that still eat large amounts of fish and shellfish, such as the Inuit and the Japanese, have in the past consistently ranked high for good health, with far lower rates of cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. But when modern, highly processed foods begin to supplant the traditional, simple, fish-rich diet of such societies, these and other health problems rapidly mount up. The rising rate of type 2 diabetes in Japan correlates nicely (or nastily) with the expansion of Western fast-food franchises in that country over the last few decades. We turn from raw fish to cheeseburgers at our peril.

The term health food doesn’t tend to whet our appetites but, taken at face value, it describes a piece of fish rather better than a packet of lentils. It’s not just the famous omega-3s that fish have to offer. Even before you tot up the vitamins and minerals, almost all types of fish and shellfish are superb sources of first-class, low-fat, highly digestible protein. And, of course, there are so many different types of seafood – among them, they offer a whole spectrum of good things. Fin fish (i.e., fish that swim with fins) are packed with vitamins (particularly A and D but also B), plus magnesium, calcium, and other trace elements. Crustaceans and other shellfish are rich in other minerals, such as iodine, zinc, and iron, plus vital selenium and taurine (essential for the healthy function of all human cells). Nevertheless, it is those omega oils that really mark fish out as a fantastic food. And some fish have far more of them than others. These are the species that we refer to by the pleasingly nontechnical term “oily fish.” They include mackerel, herring, sardines, sprats, scad (horse mackerel), tuna, salmon, trout, and eel. All of these species are especially valuable as food because they are

so rich in omega-3s – much more so than white fish. This doesn’t mean that white fish, such as haddock and plaice, isn’t good for you. Quite the opposite: white fish is low in fat and high in protein, and is a good source of vitamins and and a fabulous addition to anybody’s diet. But oily fish is even better. Oily fish is essential.

Fish as brain food

The known direct health benefits of eating oily fish include a reduced risk of heart attack and type 2 diabetes; lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels; and, for expectant mothers, higher fetal birth weight, which generally correlates with more likely future good health. There is also mounting evidence of mental and psychological benefits from a fish-rich diet.

Current research into how omega-3s affect the human brain, and thus human behavior, suggests that dramatic discoveries are just over the horizon. It dovetails neatly with our understanding of the role of fish in the evolutionary progress of Homo sapiens. After all, his success was surely due to the fact that he was not only clever but well adjusted, too.

To recap on the brain front: essential fatty acids are necessary for optimal brain function, as they are the critical components of neuron membranes. As we can’t make fatty acids, the composition of our brains is determined by the types of fat we consume. The main dietary sources of the two types of essential fatty acid are seafood (for omega-3) and seed oils (for omega-6). For optimum biological functions, these two should be well balanced in our bodies.

Over the critical years of human evolution, the dietary ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 was generally a nice, even 1:1. But as we have turned our backs on our ancestors’ diet, our consumption of omega-6 fatty acids has soared (sources include soybean oil and corn oil, as well as dairy products and red meat from grazing ruminants). In the modern Western diet, the average ratio now stands at somewhere between 15:1 to 25:1 in favor of omega-6. This staggering change cannot fail to have consequences for our brain health – and hence our mental well-being.

In 2001, a large study by Dr. Antti Tanskanen and his colleagues at Finnish Psychiatric Services looked at fish consumption and depressive symptoms. It showed that the likelihood of both clinical depression and mild depressive episodes was significantly higher for those who rarely ate fish, compared to those who regularly did. It also suggested that the rise in depression rates generally might be due to the fact that our brains were built in the Paleolithic era, on a diet that offered roughly equal amounts of omega-3 and omega-6 oils. So, now that this ratio is way off kilter, our brains are prone to serious malfunction. Which is a compelling reason to eat oily fish!

And there’s more. A deficiency in omega-3 oils has recently been linked to violent and criminal behavior. In 2001, Dr. Joseph Hibbeln of the United States Public Health Service published research that compared the murder rate in twenty-six different countries to local fish-eating habits. His study, “Homicide Mortality Rates and Seafood Consumption,” demonstrated that homicide rates decline as seafood consumption rises. In other words, if you eat plenty of omega-3-rich fish, you’re statistically a lot less likely to kill someone.

Bernard Gesch, a senior research scientist at Oxford University, explored this idea further in a 2002 study. He enrolled 230 inmates from HM Young Offenders Institute in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, and divided them into two groups. Supplements that included essential fatty acids were given to one group, a placebo to the other. The researchers recorded the number of breached regulations and episodes of antisocial behavior committed by each of the inmates in the nine months before they received the pills and in the nine months of the trial period. The group who had taken the supplements committed 25 percent fewer offenses than those who’d taken the placebo. The greatest reduction was in the number of serious offenses, including violence, which fell by a staggering 40 percent. There was no change in the behavior of the group that took the placebo.

The results of this study suggest a probable link between antisocial behavior and a diet that is deficient in essential fatty acids. There is clearly a compelling case that fish oil supplements make troublesome teens significantly less punchy. Making oily fish a regular item on the prison canteen menu can’t be a bad plan, either.

Nobody yet fully understands the reasons behind such results, but they have been consistently replicated in a whole range of studies in Europe and the United States. There certainly appears to be a relationship between a happy human brain and a diet rich in fish. This doesn’t surprise us greatly. Eating fish has always made us happy – it’s a spring-in-the-step kind of food. And it’s good to know that scientists agree with us.

We both love fish. And that is the overriding reason we have written this book. As anglers, cooks, and (very amateur) naturalists, we’ve got fish under our skin. It’s very hard – and rather stressful – to imagine life without them.

Over the years we’ve found all kinds of ways to scratch our fish itch: goldfish in a bowl, visits to aquariums, goggling at Jacques Cousteau on the telly, learning first to snorkel and then to scuba dive. Such enthusiasms have come and gone, but two have always been a constant: catching fish and eating them.

Between us, we have caught and cooked many fish. We have, of course, also caught a fair few that we haven’t cooked, and cooked countless others that we haven’t caught. But we are happiest when these two pursuits collide and we get to consume a fish that we have personally pulled from the deep. For both of us, our passion for fish as quarry and food began at an early age.

Hugh’s first fishing expedition occurred at the age of six, when his dad took him to a stream in Richmond Park, armed with a bamboo cane, a length of string, a bent pin, and a slice of bread. They actually caught a fish! Back home with his Observer’s Book of Fishes, Hugh identified the catch as a mackerel, noting that this was a fish that was meant to live in the sea.

Being omniscient, his dad naturally had a convincing explanation: “Er, it must have decided to swim up from the sea – like a salmon . . .” That was more than good enough for the young Hugh. There was no reason to be suspicious. After all, he had lifted the fish from the stream with his own hands, and watched his father knock it several times on the head with his own eyes.

Hugh’s mum fried the mackerel in butter and served it with a slice of lemon. It was the first fish Hugh had ever eaten that wasn’t finger shaped, coated in bread crumbs, and doused in ketchup – and he enjoyed it very much indeed.

It was ten years before the sorry truth came out. Seeing his teenage son swearing blind to some disbelieving friends that he had once caught a mackerel in a London park with a lump of Mother’s Pride on a bent pin, Hugh’s dad was moved to a guilty confession. He came clean about the trip to the fishmonger’s; the sleight of hand that slipped the fish onto the hook as Hugh was sent behind a bush for a much-needed pee; the ritual dispatch of a fish that had, in fact, already been dead for two days . . .

Hugh was a little disillusioned to discover the deceit but, being sixteen, soon found other things to strop about. In the end he is, of course, eternally grateful to his dad. Grateful to be hooked on fishing, and hooked on fish.

1. Understanding fish

The nitty-gritty of this book is the delightful activity of cooking and eating fish. And we think you’ll derive even more pleasure from your fish and shellfish if you understand a little, or perhaps a lot, about the business of catching and preparing them.

Besides being delicious, fish are uniquely nutritious. So you would think the very least we could do, given their contribution to our well-being, would be to nurture them in return. At this we are failing spectacularly. The prognosis is gloomy on a number of fronts, as the destructive fishing practices of the past half-century have taken their toll. The fact that we can finally acknowledge just how bad things are does offer, paradoxically, a glimmer of hope. We haven’t, thank goodness, passed the point of no return; we still have a stunning range of native fish and shellfish to celebrate. We would both argue that their future lies largely in the hands of the consumer – that’s every single one of us who loves to eat fish.

The angler-cook will, of necessity, prepare much of his or her fish from scratch, and knowing how to wield a filleting knife is clearly essential. But even the landlubber fish enthusiast may once in a while enjoy taking a live crab home or gutting a mackerel at the sink. Our two chapters covering fish and shellfish skills will show you the way.

Four million years ago, an early prototype of the human being, australopithecine man, roamed across the African savannah. He walked upright, stood around 4 feet (1.2m) tall and possessed a brain about the size of a chimp’s. Three million years later, on the verge of extinction, he hadn’t changed much. Despite a few hundred thousand generations of hunting and eating meat, Australopithecus remained pretty much as intellectually and vertically challenged as he had been when he first wandered out onto the plain. He lost the battle for survival – and became just another leaf to have fallen from the evolutionary tree.

Another human forerunner, who overlapped with Australopithecus for the last million years of his time on the planet, was Homo erectus. He grew over 5 feet (1.5m) tall, and in just 200,000 years of evolution he tripled the size of his brain. Equipped with this enlarged gray matter and a range of tools, erectus evolved into sapiens. Hom sap was anatomically modern and technologically minded; in other words, he was us.

Why did one branch of protohumans hit an evolutionary dead end while another grew bigger, stronger, and – crucially – much cleverer? What made one a hopeless, doomed grunter and the other the ancestor of Leonardo da Vinci (plus you and us, of course). The answer is fish.

Homo erectus stood up, but he didn’t stand still. He wandered all over the place, in search of a better living; he left the savannah and reached the coast, where he ate fish, shellfish, and seaweed for the first time (they must have made a nice change from mastodons – so much easier on the teeth). Fossil evidence shows that his burgeoning fish-eating habit coincided with his rapid cerebral growth. Scientists believe this staggering improvement came about because Homo sapiens was nourished by a substance previously present only in trace quantities in his diet: docosahexaenoic acid, or DHA for short. Our bodies aren’t able to manufacture their own DHA, so how did it end up inside them? It must have been something we ate. When it comes to identifying the “superfood” that provided the quantities of DHA necessary for the dramatic expansion of our cranial capacity, the only serious candidate is fish.

DHA is an omega-3 essential fatty acid, of the kind we now know to be vital to brain development. The body converts it into proteins, which it uses specifically to build neurons – the conductors that manage electrochemical activity in the brain. Up to 8 percent of our brain weight is made up of these fatty acids, so to achieve optimal brain growth we need fatty acids in our food. Put simply, the more of them we get, the better our brains develop. And there’s nowhere better

to get them than from fish.

So if it hadn’t been for early man’s trip to the seaside, we might all still be hairy bush dwellers, waiting for someone to invent the wheel (or at least the fish spear). Of course, we should remember that we didn’t become piscivores in order to evolve. We weren’t quite that clever. We ate fish because they were there, they sustained us, and perhaps because we found them delicious. It just so happens that, from a biological and evolutionary perspective, actively choosing to eat something that is so good for you makes for a fantastically virtuous circle. One that has led, down the millennia, to a culture of such stupendous sophistication that books have been written and television shows filmed about our favorite ways of eating fish (among other things).

Fish for health

A fish-rich diet continues to contribute to our well-being. Those cultures that still eat large amounts of fish and shellfish, such as the Inuit and the Japanese, have in the past consistently ranked high for good health, with far lower rates of cancer, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. But when modern, highly processed foods begin to supplant the traditional, simple, fish-rich diet of such societies, these and other health problems rapidly mount up. The rising rate of type 2 diabetes in Japan correlates nicely (or nastily) with the expansion of Western fast-food franchises in that country over the last few decades. We turn from raw fish to cheeseburgers at our peril.

The term health food doesn’t tend to whet our appetites but, taken at face value, it describes a piece of fish rather better than a packet of lentils. It’s not just the famous omega-3s that fish have to offer. Even before you tot up the vitamins and minerals, almost all types of fish and shellfish are superb sources of first-class, low-fat, highly digestible protein. And, of course, there are so many different types of seafood – among them, they offer a whole spectrum of good things. Fin fish (i.e., fish that swim with fins) are packed with vitamins (particularly A and D but also B), plus magnesium, calcium, and other trace elements. Crustaceans and other shellfish are rich in other minerals, such as iodine, zinc, and iron, plus vital selenium and taurine (essential for the healthy function of all human cells). Nevertheless, it is those omega oils that really mark fish out as a fantastic food. And some fish have far more of them than others. These are the species that we refer to by the pleasingly nontechnical term “oily fish.” They include mackerel, herring, sardines, sprats, scad (horse mackerel), tuna, salmon, trout, and eel. All of these species are especially valuable as food because they are

so rich in omega-3s – much more so than white fish. This doesn’t mean that white fish, such as haddock and plaice, isn’t good for you. Quite the opposite: white fish is low in fat and high in protein, and is a good source of vitamins and and a fabulous addition to anybody’s diet. But oily fish is even better. Oily fish is essential.

Fish as brain food

The known direct health benefits of eating oily fish include a reduced risk of heart attack and type 2 diabetes; lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels; and, for expectant mothers, higher fetal birth weight, which generally correlates with more likely future good health. There is also mounting evidence of mental and psychological benefits from a fish-rich diet.

Current research into how omega-3s affect the human brain, and thus human behavior, suggests that dramatic discoveries are just over the horizon. It dovetails neatly with our understanding of the role of fish in the evolutionary progress of Homo sapiens. After all, his success was surely due to the fact that he was not only clever but well adjusted, too.

To recap on the brain front: essential fatty acids are necessary for optimal brain function, as they are the critical components of neuron membranes. As we can’t make fatty acids, the composition of our brains is determined by the types of fat we consume. The main dietary sources of the two types of essential fatty acid are seafood (for omega-3) and seed oils (for omega-6). For optimum biological functions, these two should be well balanced in our bodies.

Over the critical years of human evolution, the dietary ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 was generally a nice, even 1:1. But as we have turned our backs on our ancestors’ diet, our consumption of omega-6 fatty acids has soared (sources include soybean oil and corn oil, as well as dairy products and red meat from grazing ruminants). In the modern Western diet, the average ratio now stands at somewhere between 15:1 to 25:1 in favor of omega-6. This staggering change cannot fail to have consequences for our brain health – and hence our mental well-being.

In 2001, a large study by Dr. Antti Tanskanen and his colleagues at Finnish Psychiatric Services looked at fish consumption and depressive symptoms. It showed that the likelihood of both clinical depression and mild depressive episodes was significantly higher for those who rarely ate fish, compared to those who regularly did. It also suggested that the rise in depression rates generally might be due to the fact that our brains were built in the Paleolithic era, on a diet that offered roughly equal amounts of omega-3 and omega-6 oils. So, now that this ratio is way off kilter, our brains are prone to serious malfunction. Which is a compelling reason to eat oily fish!

And there’s more. A deficiency in omega-3 oils has recently been linked to violent and criminal behavior. In 2001, Dr. Joseph Hibbeln of the United States Public Health Service published research that compared the murder rate in twenty-six different countries to local fish-eating habits. His study, “Homicide Mortality Rates and Seafood Consumption,” demonstrated that homicide rates decline as seafood consumption rises. In other words, if you eat plenty of omega-3-rich fish, you’re statistically a lot less likely to kill someone.

Bernard Gesch, a senior research scientist at Oxford University, explored this idea further in a 2002 study. He enrolled 230 inmates from HM Young Offenders Institute in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, and divided them into two groups. Supplements that included essential fatty acids were given to one group, a placebo to the other. The researchers recorded the number of breached regulations and episodes of antisocial behavior committed by each of the inmates in the nine months before they received the pills and in the nine months of the trial period. The group who had taken the supplements committed 25 percent fewer offenses than those who’d taken the placebo. The greatest reduction was in the number of serious offenses, including violence, which fell by a staggering 40 percent. There was no change in the behavior of the group that took the placebo.

The results of this study suggest a probable link between antisocial behavior and a diet that is deficient in essential fatty acids. There is clearly a compelling case that fish oil supplements make troublesome teens significantly less punchy. Making oily fish a regular item on the prison canteen menu can’t be a bad plan, either.

Nobody yet fully understands the reasons behind such results, but they have been consistently replicated in a whole range of studies in Europe and the United States. There certainly appears to be a relationship between a happy human brain and a diet rich in fish. This doesn’t surprise us greatly. Eating fish has always made us happy – it’s a spring-in-the-step kind of food. And it’s good to know that scientists agree with us.

Recenzii

“A thorough, thoughtful 608-page guide to finding and eating ‘good’ fish.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Hugh is the person to go to for a properly informed and insightful read on almost any food subject. This fish book is no exception. It is illuminating, original, and utterly delicious, offering a solid background on the matter, including basic techniques and an abundance of original recipes.”

—Yotam Ottolenghi, author of Plenty

“Fearnley-Whittingstall and Fisher’s comprehensive instructions on the mechanics of cleaning and preparing fish are worth the price of the book alone, but their fondness for typically unloved species of fish—mackerel, sea robins, sand dabs, and the like—makes this an indispensible book for any serious piscivore.”

—Hank Shaw, author of Hunt Gather Cook: Finding the Forgotten Feast

—New York Times Book Review

“Hugh is the person to go to for a properly informed and insightful read on almost any food subject. This fish book is no exception. It is illuminating, original, and utterly delicious, offering a solid background on the matter, including basic techniques and an abundance of original recipes.”

—Yotam Ottolenghi, author of Plenty

“Fearnley-Whittingstall and Fisher’s comprehensive instructions on the mechanics of cleaning and preparing fish are worth the price of the book alone, but their fondness for typically unloved species of fish—mackerel, sea robins, sand dabs, and the like—makes this an indispensible book for any serious piscivore.”

—Hank Shaw, author of Hunt Gather Cook: Finding the Forgotten Feast

Cuprins

Introduction 9

1. Understanding fish 14

Fish as food 17

Sourcing fish 26

Fish skills 51

Shellfish skills 87

2. Fish cookery 110

Raw, salted, and marinated fish 119

Smoked fish 153

Open-fire cooking 185

Baked and broiled fish 211

Soups, stews, and poaching 249

Shallow and deep-frying 293

Cold fish and salads 343

Fish thrift and standbys 367

3. Guide to fish and shellfish 410

Sea fish 415

Freshwater fish 506

Shellfish 538

Notes to the US edition 590

Index 595

Bibliography 606

Acknowledgments 607

1. Understanding fish 14

Fish as food 17

Sourcing fish 26

Fish skills 51

Shellfish skills 87

2. Fish cookery 110

Raw, salted, and marinated fish 119

Smoked fish 153

Open-fire cooking 185

Baked and broiled fish 211

Soups, stews, and poaching 249

Shallow and deep-frying 293

Cold fish and salads 343

Fish thrift and standbys 367

3. Guide to fish and shellfish 410

Sea fish 415

Freshwater fish 506

Shellfish 538

Notes to the US edition 590

Index 595

Bibliography 606

Acknowledgments 607

Descriere

"The River Cottage Fish Book" is the definitive guide to catching, buying, cooking, and eating fish and shellfish, with an emphasis on making sustainable food choices.