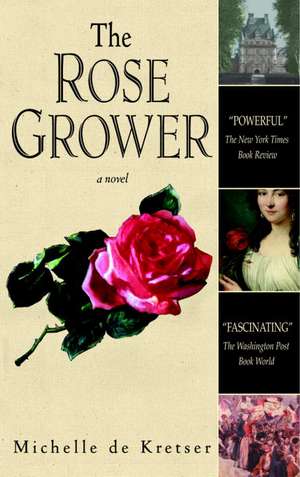

The Rose Grower

Autor Michelle De Kretseren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2001

The 1789 storming of the Bastille has brought France to the brink of revolution. Yet in the serene heart of the French province of Gascony, little has changed in a hundred years -- and the events in Paris seem but a distant thunder.

Indeed, the dramatic crash landing of American artist and amateur balloonist Stephen Fletcher sparks far more excitement. Stephen lands in the pastoral world of a magistrate and his three daughters -- ethereal Claire, pert and precocious Mathilde, and plain, sensible Sophie, who lovingly tends her rose garden as she simmers with unfulfilled longings.

As the revolution brings murder, terror, and fear into the remote Gascon countryside, Stephen finds himself enchanted by the angelic Claire. Yet he is also strangely drawn to Sophie, whose courage and compassion sustain them all, from her family to the quixotic, tormented physician who silently adores her. And even as Sophie keeps a tender secret of her own, she works toward realizing yet another dream: the miracle of an original repeat-flowering crimson rose -- a hopeful symbol of an unblighted future.

Preț: 74.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 111

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.21€ • 14.68$ • 11.83£

14.21€ • 14.68$ • 11.83£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553381214

ISBN-10: 0553381210

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 133 x 210 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Bantam Trade Pb.

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553381210

Pagini: 336

Dimensiuni: 133 x 210 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Bantam Trade Pb.

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Michelle de Kretser was born in Colombo in Sri Lanka. She emigrated at 14 with part of her family to Melbourne, where she now lives. She worked for many years for Lonely Planet, and took a sabbatical to write a novel.

Extras

On a cloudless summer afternoon in 1789, labourers working in the fields around Montsignac, a village in Gascony, saw a man fall out of the sky.

The balloon had drifted over a wooded ridge and into their valley. The farm-workers, straightening up one by one, shaded their eyes against the dazzle of sun on crimson and blue silk. The thing hung in the sky — sumptuous, menacing — like a sign from God or the devil.

Then there was thunder and fire, and a man plummeting earthwards.

It was the 14th of July. The world was about to change.

Stephen opened his eyes and fell in love.

It was right and natural that it should happen that way: he believed, like so many of his generation, in the coup de foudre — the lightning flash which reveals the lie of the land between a man and a woman. “An angel,” he sighed, not caring who might hear.

At once her face moved away, out of his field of vision. There was the sound of vigorous scratching.

He was propped up against cushions on a crimson sofa carved with scallop shells. There was slanting light, mote-speckled, and the scent of roses. He took in the old-fashioned beams, on which blue and red flowers had once been painted, and the unpapered walls. But as usual it was the pictures he really noticed: the large one directly opposite him showed a maiden with a basket of fruit, and the rest were no better. He had imagined that kind of thing would be different in France.

An elderly servant, long and thin as a nail, served him from a decanter on a silver tray. He sipped — was it brandy? something that made him choke — and looked around for her.

She was seated by the window, her head bent over a small garment at which she was stitching. But a child of about eight, solemn-faced and weighed down with dark curls, planted herself in front of him.

“Are you fatally injured? If you live, will you take me ballooning?”

“Mathilde, someone who has suffered an accident is ill-equipped for your conversation.” Stephen turned his head and saw a stout man in a mustard-yellow waistcoat, standing in front of the fireplace. “I envisage a speedier recovery for our visitor if you remove yourself from his vicinity. And take Brutus with you.”

Unperturbed, the child continued to gaze at Stephen with expectant curiosity. “I adore children,” he said and smiled at her. “They are so ... innocent and yet so perceptive in their apprehension of the world.”

“Oh no — another Rousseauist,” said the child with unconcealed disappointment. “I’m not like that at all.”

As she spoke, something manifested itself on the far side of the room. Stephen saw a squat black form, a squashed-in muzzle, a formidable underbite that exposed a row of yellow fangs. Swiftly and noiselessly, the apparition padded up to him and thrust its cold nose between his legs.

His knuckles whitened around his glass.

A tall young woman, whom he had not previously noticed, said, “Brutus!”

The creature withdrew its muzzle an inch or so and sneezed, scattering cold droplets. Its eyes were amber and unwavering, and made no secret of its low opinion of the intruder.

“It’s quite all right,” the child said kindly. “He doesn’t bite many people these days. He used to be much worse.”

“I trust you find the intelligence reassuring.” The stout gentleman crossed the room, obliging the dog to give reluctant ground. Stephen found himself looking up at panoramic grey eyebrows, and sharp brown eyes that pinned an enormous beaky nose into place. “Jean-Baptiste de Saint-Pierre” — holding out his hand — ”Welcome to Montsignac.”

“Stephen Fletcher.” He attempted to get to his feet but Saint-Pierre wouldn’t allow it, waving him back onto the cushions. Brown eyes and yellow ones continued their unhurried scrutiny of his person.

Eventually: “English?”

“American.”

“Really? Then no doubt you have an opinion about turkeys.”

Stephen had just decided that a turkey must be something entirely different in France, when his host added, “But you speak our language very well.”

He identified it as a question. “I’m afraid you exaggerate. But my mother is a Frenchwoman, and since my father’s death we’ve lived with her family.”

The explanation seemed to satisfy Saint-Pierre. “Well, Mr. Fletcher, you appear not to have suffered any serious harm as a result of your unexpected descent into our midst.”

He had been away from home long enough to recognise that he was being gently mocked. Old World conversations required athleticism, a series of leaps between words and what they might mean. That was another thing he had not been prepared for.

“No. That is, I mean...” He wriggled experimentally and regretted it: “My ankle...” He drank more brandy and asked, “What happened?”

“Reports vary. My own conclusion, based on the available evidence, is that you leapt from a balloon that had caught fire. Fortunately, you landed on one of my haystacks. Some villagers carried you here. A doctor has been sent for, but the town is a few miles away.”

One of the young women — not the angel but the tall one — said, “Father, if the gentleman has hurt his ankle it’ll swell up. He should take off his boot.”

At this, the servant creaked forward. “No sense at all,” he remarked, to no one in particular, between bootlaces.

Saint-Pierre said, “Allow me to present my daughters, Mr. Fletcher. Mathilde you are already acquainted with. Then there is Sophie” — she nodded shyly at him — ”and Claire, my eldest.”

The angel looked into his eyes and smiled. Not an angel after all, thought Stephen, but the Madonna herself, with that blue dress.

(Though not perhaps the way it clung to her body.)

“Madame la Marquise de Monferrant,” murmured Saint-Pierre, his head on one side, detached, observing.

Somehow the back of Stephen’s hand struck the decanter, sending it crashing. The dog surged forward and fastened its jaws onto his shin.

The balloon had drifted over a wooded ridge and into their valley. The farm-workers, straightening up one by one, shaded their eyes against the dazzle of sun on crimson and blue silk. The thing hung in the sky — sumptuous, menacing — like a sign from God or the devil.

Then there was thunder and fire, and a man plummeting earthwards.

It was the 14th of July. The world was about to change.

Stephen opened his eyes and fell in love.

It was right and natural that it should happen that way: he believed, like so many of his generation, in the coup de foudre — the lightning flash which reveals the lie of the land between a man and a woman. “An angel,” he sighed, not caring who might hear.

At once her face moved away, out of his field of vision. There was the sound of vigorous scratching.

He was propped up against cushions on a crimson sofa carved with scallop shells. There was slanting light, mote-speckled, and the scent of roses. He took in the old-fashioned beams, on which blue and red flowers had once been painted, and the unpapered walls. But as usual it was the pictures he really noticed: the large one directly opposite him showed a maiden with a basket of fruit, and the rest were no better. He had imagined that kind of thing would be different in France.

An elderly servant, long and thin as a nail, served him from a decanter on a silver tray. He sipped — was it brandy? something that made him choke — and looked around for her.

She was seated by the window, her head bent over a small garment at which she was stitching. But a child of about eight, solemn-faced and weighed down with dark curls, planted herself in front of him.

“Are you fatally injured? If you live, will you take me ballooning?”

“Mathilde, someone who has suffered an accident is ill-equipped for your conversation.” Stephen turned his head and saw a stout man in a mustard-yellow waistcoat, standing in front of the fireplace. “I envisage a speedier recovery for our visitor if you remove yourself from his vicinity. And take Brutus with you.”

Unperturbed, the child continued to gaze at Stephen with expectant curiosity. “I adore children,” he said and smiled at her. “They are so ... innocent and yet so perceptive in their apprehension of the world.”

“Oh no — another Rousseauist,” said the child with unconcealed disappointment. “I’m not like that at all.”

As she spoke, something manifested itself on the far side of the room. Stephen saw a squat black form, a squashed-in muzzle, a formidable underbite that exposed a row of yellow fangs. Swiftly and noiselessly, the apparition padded up to him and thrust its cold nose between his legs.

His knuckles whitened around his glass.

A tall young woman, whom he had not previously noticed, said, “Brutus!”

The creature withdrew its muzzle an inch or so and sneezed, scattering cold droplets. Its eyes were amber and unwavering, and made no secret of its low opinion of the intruder.

“It’s quite all right,” the child said kindly. “He doesn’t bite many people these days. He used to be much worse.”

“I trust you find the intelligence reassuring.” The stout gentleman crossed the room, obliging the dog to give reluctant ground. Stephen found himself looking up at panoramic grey eyebrows, and sharp brown eyes that pinned an enormous beaky nose into place. “Jean-Baptiste de Saint-Pierre” — holding out his hand — ”Welcome to Montsignac.”

“Stephen Fletcher.” He attempted to get to his feet but Saint-Pierre wouldn’t allow it, waving him back onto the cushions. Brown eyes and yellow ones continued their unhurried scrutiny of his person.

Eventually: “English?”

“American.”

“Really? Then no doubt you have an opinion about turkeys.”

Stephen had just decided that a turkey must be something entirely different in France, when his host added, “But you speak our language very well.”

He identified it as a question. “I’m afraid you exaggerate. But my mother is a Frenchwoman, and since my father’s death we’ve lived with her family.”

The explanation seemed to satisfy Saint-Pierre. “Well, Mr. Fletcher, you appear not to have suffered any serious harm as a result of your unexpected descent into our midst.”

He had been away from home long enough to recognise that he was being gently mocked. Old World conversations required athleticism, a series of leaps between words and what they might mean. That was another thing he had not been prepared for.

“No. That is, I mean...” He wriggled experimentally and regretted it: “My ankle...” He drank more brandy and asked, “What happened?”

“Reports vary. My own conclusion, based on the available evidence, is that you leapt from a balloon that had caught fire. Fortunately, you landed on one of my haystacks. Some villagers carried you here. A doctor has been sent for, but the town is a few miles away.”

One of the young women — not the angel but the tall one — said, “Father, if the gentleman has hurt his ankle it’ll swell up. He should take off his boot.”

At this, the servant creaked forward. “No sense at all,” he remarked, to no one in particular, between bootlaces.

Saint-Pierre said, “Allow me to present my daughters, Mr. Fletcher. Mathilde you are already acquainted with. Then there is Sophie” — she nodded shyly at him — ”and Claire, my eldest.”

The angel looked into his eyes and smiled. Not an angel after all, thought Stephen, but the Madonna herself, with that blue dress.

(Though not perhaps the way it clung to her body.)

“Madame la Marquise de Monferrant,” murmured Saint-Pierre, his head on one side, detached, observing.

Somehow the back of Stephen’s hand struck the decanter, sending it crashing. The dog surged forward and fastened its jaws onto his shin.

Recenzii

"If Jane Austen had been French, she might well have invented the family Saint-Pierre.... Stylish and uniquely crafted."

-- The Orlando Sentinel

"Powerful ... lovely, meticulously researched ... evokes the beginnings of the Terror in crisp, elegant, compassionate prose."

-- The New York Times Book Review

"Fascinating ... Sophie's calmness and kindness, her passion for roses, her botanical studies and attempts to create a crimson flower ... are the soul and spine of the book.... De Kretser has exhaustively researched the life of the period, but she wears her knowledge lightly."

-- The Washington Post Book World

-- The Orlando Sentinel

"Powerful ... lovely, meticulously researched ... evokes the beginnings of the Terror in crisp, elegant, compassionate prose."

-- The New York Times Book Review

"Fascinating ... Sophie's calmness and kindness, her passion for roses, her botanical studies and attempts to create a crimson flower ... are the soul and spine of the book.... De Kretser has exhaustively researched the life of the period, but she wears her knowledge lightly."

-- The Washington Post Book World

Descriere

In July 1789, the devastation of the French Reign of Terror forever alters the lives of three sisters: the precocious Mathilde, the angelic Claire, and the tall, plainspoken Sophie who refuses to relinquish the miracles of her extraordinary rose garden.