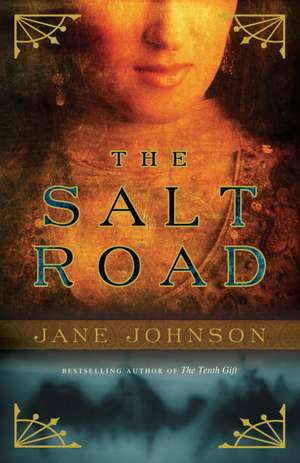

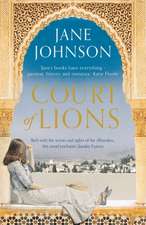

The Salt Road

Autor Jane Johnsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2011

"My dear Isabelle, in the attic you will find a box with your name on it."

Isabelle's estranged archeologist father dies, leaving her a puzzle. In a box she finds some papers and a mysterious African amulet — but their connection to her remains unclear until she embarks on a trip to Morocco to discover how the amulet came into her father's possession. When the amulet is damaged and Isabelle almost killed in an accident, she fears her curiosity has got the better of her. But Taib, her rescuer, knows the dunes and their peoples, and offers to help uncover the amulet's extraordinary history, involving Tin Hinan — She of the Tents — who made a legendary crossing of the desert, and her beautiful descendant Mariata.

Across years and over hot, shifting sands, tracking the Salt Road, the stories of Isabelle and Taib, Mariata and her lover, become entangled with that of the lost amulet. It is a tale of souls wounded by history and of love blossoming on barren ground.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 97.91 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.74€ • 20.36$ • 15.75£

18.74€ • 20.36$ • 15.75£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385670012

ISBN-10: 038567001X

Pagini: 390

Dimensiuni: 163 x 202 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

ISBN-10: 038567001X

Pagini: 390

Dimensiuni: 163 x 202 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: ANCHOR CANADA

Notă biografică

JANE JOHNSON is a writer for adults and children.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

When I was a child, I had a wigwam in our back garden: a circle of thin yellow cotton draped over a bamboo pole and pegged to the lawn. Every time my parents argued, that was where I went. I would lie on my stomach with my fingers in my ears and stare so hard at the red animals printed on its bright decorative border that after a while they began to dance and run, until I wasn’t in the garden any more but out on the plains, wearing a fringed deerskin tunic and feathers in my hair, just like the braves in the films I watched every Saturday morning in the cinema down the road.

Even at an early age I found it preferable to be outside in my little tent rather than inside the house. The tent was my space. It was as large as my imagination, which was infinite. But the house, for all its grandeur and Georgian spaciousness, felt small and suffocating. It was stuffed with things, as well as with my mother and father’s bitterness. They were both archaeologists, my parents: lovers of the past, they had surrounded themselves with boxes of yellowed papers, ancient artefacts, dusty objects; the fragile, friable husks of lost civilizations. I never understood why they decided to have me: even the quietest baby, the most house-trained toddler, the most studious child, would have disrupted the artificial, museum-like calm they had wrapped around themselves. In that house they lived separated from the rest of the world, in a bubble in which dust motes floated silently like the fake snow in a snow-globe. I was not the child to complement such a life, being a wild little creature, loud and messy and unbiddable. I liked to play rough games with the boys instead of engaging in the sedate, codified exchanges of the other girls. I had dolls, but more often than not I beheaded or scalped them, or buried them in the garden and forgot where they were. I had no interest in making fashionable outfits for the oddly attenuated pink plastic mannequins with their insectile torsos and brassy hair that the other girls so worshipped and adorned. I had little interest even in my own clothes: I preferred making mud missiles and catapults and chasing my playmates till my sides hurt from a combination of laughing and stitches, building hides and running around half naked, even in the winter.

‘You little savage!’ my mother would admonish, accompanying the words with a sharp smack on the backside. ‘For God’s sake put some clothes on, Isabelle.’ She would say this with all the severity her clipped French accent could deliver, as if she thought she could imprint civilized behaviour on me by the use of the full version of my old-fashioned name. But it never really worked.

My friends called me Izzy: it fitted the chaos of me, always buzzing, always noisy – such a trial.

In the garden behind our house my friends and I played at being cowboys and Indians, Zulus, King Arthur and Robin Hood, armed with swords and spears in the form of bamboo canes robbed from the vegetable patch, and make-believe bows and arrows. When it came to the Robin Hood game I always insisted on playing a merry man, or even the Sheriff of Nottingham – anything other than Maid Marian. In all the versions of the legend I’d come across Maid Marian didn’t do very much except get imprisoned and/or rescued, which didn’t greatly appeal to me. I had no interest in being the swooning prisoner: I wanted to wrestle and hit people with sticks, like the rough little tomboy I was. This was in the late sixties and early seventies: girlpower hadn’t yet turned Maid Marian, Guinevere, Arwen or any of the other complaisant heroines of legend into feisty, all-action go-getters. Besides, in comparison with the pale, pretty girls who were my friends, I was too ugly to play the heroine. I didn’t care: I liked being ugly. I had thick, black hair and dirty skin and earth under my nails and calluses on my feet, and that was how I preferred it. How I howled when my mother made me take a bath, when she attacked me with Wright’s coal tar soap, or tried to untangle my hair. If guests were staying at the house, as they occasionally did, she had to warn them, ‘Take no notice of the screaming: it’s only Isabelle. She hates having her hair washed.’

You’d never have recognized me three decades later.

The day I went to the solicitor’s office to take charge of the letter my father had left me in his will I wore a classic Armani trouser suit and Prada heels. My unruly hair was cut and straightened into a neat shoulder-length bob; my make-up was discreet and expertly applied. The dirt under my nails had been replaced with a practical square-cut French manicure. Ironic, really: I now presented myself in a manner of which my mother would have thoroughly approved, had she still been alive. It was hard even for me, who had travelled every step of the long path between the grubby little hooligan I had once been and the carefully turned-out businesswoman I had become, to reconcile the two.

The letter he left for me was short and cryptic, which was apposite: my father was a short and cryptic sort of man. It said:

My dear Isabelle

I know I have been a great disappointment to you, as a father and as a man. I do not ask for forgiveness, or even understanding. What I did was wrong: I knew it then, and I know it now. One bad decision leads to another and another and another; a chain of events leading to catastrophe. There is a story behind this catastrophe to be told, but I am not the one to tell it. It is something you need to piece together for yourself, for it belongs to you and I do not want to reinterpret it for you, or to spoil it as I have spoiled everything else. So I am leaving you the house: and something else besides. In the attic you will find a box with your name on it. Inside that box are what you might call ‘waymarkers’ for your life. I know you have always felt at odds with the world in which you found yourself, and I must take at least half of the blame for that; but perhaps by now you have come to terms with it. If that is indeed the case, forget this letter. Do not open the box. Sell the house and everything in it. Let sleeping beasts lie. Go in peace, Isabelle, and with my love. For the little it is worth.

Anthony Treslove-Fawcett

I read this in the lawyer’s office in Holborn, a brisk ten-minute walk away from the office where I worked as a highly paid tax accountant, with the solicitor and his clerk watching on curiously. Also in the envelope, a set of house keys on a battered leather fob.

‘All well?’ the solicitor asked brightly. A strange question to ask someone whose father has just died; though maybe he was not to know that I had not seen that father in the best part of thirty years; not in person, at least.

I was shaking so much I could hardly speak. ‘Yes, thank you,’ I replied, stowing the letter and keys clumsily into my handbag. Summoning every ounce of resolve, I gave him a smile so bright it would have dazzled blind Justice herself.

The senior partner tried not to show his disappointment at my failure to disclose the contents. Then he passed me a folder of papers and started to talk very fast.

All I wanted was to be outside now. I needed sunlight on me; I needed outdoor space. I could feel the walls of the office – its stacked shelves and massive filing cabinets – closing in on me. The words ‘probate’ and ‘frozen accounts’ and ‘legal process’ came at me thick and fast, a maddening buzz of flies in the back of my skull. While he was still in mid-sentence, I wrenched open the door, stepped out into the corridor and fled down the stairs.

When my father left us, I was fourteen. I had not cried, not one tear. I had mixed feelings about his absence: I hated him for walking out, despised him for running away and abandoning us; but from time to time I suffered flashes of mourning for the father he had occasionally shown himself to be and also felt a considerable relief that he was not there any more. It made life easier, if colder and poorer. My mother did not show the distress his disappearance must have caused her. She was not a demonstrative woman, my mother, and I didn’t understand her: she remained a mystery to me throughout my life. My father, with his volcanic temper and choleric disposition, seemed more like me; but my mother was a perfect Ice Queen, chilly and polite, interested only in the outward face one turned to the world. When it came to child-rearing she made it her business to monitor my progress at school, my appearance, my manners. She found emotional display vulgar, and I must have been a terrible disappointment to her with my exuberance and rages. She treated me with a sort of cool impatience, a repressed exasperation, forever repeating her corrections and strictures as if I were an espaliered pear tree that constantly needed lopping in order to make it grow along the correct lines. For most of my life I thought all mothers were like this.

But one day when I returned from school there was something different in the atmosphere of the house, something charged and threatening, as if an electric storm was lurking inside. I found my mother sitting in the half-dark with the curtains drawn. ‘Are you OK?’ I asked, scared suddenly by the idea of losing a second parent.

I pulled the curtains back and the harsh late-afternoon sunlight obliterated her features, making her face a flat white Kabuki mask, turning her into a foreign, disturbing presence. For a moment this faceless woman sat staring at me as if I were a stranger. Then at last she said, ‘Everything was wonderful between us until you came along. I knew you would ruin everything from the first moment I held you in my hands.’ She paused. ‘Sometimes you just know these things. I told him that I never wanted children; but he was so determined.’ She fixed me with her dark eyes and I was appalled by the quiet malevolence I glimpsed there.

Long moments passed and I felt my heart beating wildly. Then she smiled at me and started to talk about the rhododendrons in the garden.

The next day she was just the same as usual. She clicked her tongue over the state of my uniform (I had fallen asleep in it and it was crumpled and ruined) and tried to make me take it off so that she could iron it, but I was out of the door quickly. From that day on I lived as if I were walking across the surface of a frozen lake, terrified that the fragile, apparent surface might at any moment give way, plunging me into the roiling darkness I had glimpsed beneath. Of course, no one else knew about our strange and strained relationship: who was there to tell, and what was there to say? Abandoned by one parent, afraid of another sudden glimpse of the terrifying void inside the other, I realized I was on my own; and so as the years rolled on I devoted myself to being self-sufficient, not just in terms of financial means but in all the ways that matter, sealing myself off from need and desire and pain, making a bubble around myself that no one could penetrate.

But that evening at my kitchen table when I reread the letter I knew that bubble was about to be shattered.

Forget this letter. Do not open the box. Sell the house and everything in it. Let sleeping beasts lie . . .

Was there ever a farewell letter so guaranteed to torment? Whatever did he mean by ‘sleeping beasts’? The phrase plagued me. It also filled me with a mysterious, deep-seated excitement. My life had been so settled, so dull, for so long: but I sensed that something was about to change.

At the gym the next morning I determinedly ran and stepped and skied and pulled weights for an hour. I showered, dressed in Chanel and arrived at my office at precisely ten minutes before nine, as I did every working day. There, I switched on the computer, examined my calendar and made a list of the day’s tasks, allotting times and precedence to each of them.

I had sought security in all aspects of my life, and as Benjamin Franklin’s old saw goes, there is nothing sure in life but death and taxes. Not much fancying the trade of an undertaker, I had opted for the latter. As a corporate tax accountant my working life ran in a smooth routine from day to day. Most nights I’d leave the office at half past six, catch the tube and train home, put together a simple meal and read a book, watch the news on television and go to bed, alone, before eleven. Occasionally, I’d go into town and meet a friend; or a stranger. Sometimes I went to the indoor wall at the Westway or the Castle and climbed like a demon: my one concession to the lost Izzy trapped within. And that was my life.

I kept no ties to the girl I had been. Except for Eve.

I had known Eve since I was thirteen and she had moved into the area with her father. Eve was everything I was not: pretty, funny and more sophisticated than the rest of us, who were busy with trying to stick safety pins in our ears and join, rather belatedly, the punk revolution. Eve wore authentic Westwood bondage trousers and ripped T-shirts tied artfully at the waist; with all this and her dandelion-blonde hair she looked like Debbie Harry. Everyone loved Eve, but for some reason it was me she chose as her friend, and it was Eve I turned to that first Saturday morning after taking receipt of my father’s bombshell of a letter.

‘Come over,’ I said. ‘I need some moral support.’

At the other end of the phone, her laugh rang out. ‘You hardly need me for that! Give me half an hour, I’ll be over for some immoral support. Much more fun.’

She’d come to the funeral with me, and cried till her eyes were red, while I remained stone-faced throughout. Everyone who didn’t know me had thought she was Anthony’s daughter. ‘He was nice, your dad,’ she said now, turning her coffee cup around in her hands. ‘Remember when Tim Fleming broke my heart?’

Tim Fleming had been seventeen to our thirteen, louche, long-haired and leather-jacketed. Going out with him was just asking for trouble, which was exactly what Eve wanted, and got. I grinned. ‘Who could forget?’

‘Your father gave me that look of his – you know’ – she put her head on one side and fixed me with a beady eye; it was an absurd exaggeration of his most quizzical expression but strangely accurate – ‘and said: “Pretty girl like you, you’re wasted on a git like that.” It was so funny, a word like that being said in that incredibly posh accent of his: I just burst out laughing. And that’s what I told him myself when I saw him next, remember? “I’m wasted on a git like you!”’

I remembered Eve striding up to Tim Fleming outside the kebab shop, where he was mooching around that Saturday lunchtime with the rest of his friends, and shouting the words out, her blonde hair flying like a banner. She’d seemed so bright and defiant, and I was so proud of her. Hers was not the image of my father I most often remembered, though.

She read my father’s letter, frowning in concentration, then read it again. ‘Weird,’ she said at last and handed it back to me. ‘A box in an attic, eh? Do you think your mother’s corpse is in it, mouldering away? Perhaps she never died in France at all.’ She made a Gothic face at me. The eyeliner beneath her left eye had smudged. I itched to reach over and wipe it away, not out of any lesbian urge but purely for the sake of tidiness.

‘Oh, she went back to France, all right.’

As soon as I left to go to university, as if abnegated of all responsibility for me, my mother had sold her share of the house back to my father for some astronomical sum (I had not realized they were even in contact) and gone back to France. I visited her there twice before she died; and each time she was as distant and polite as a passing acquaintance. Each time I sensed dark shadows gliding beneath the composed exterior, and knew that if those shadows were to surface they would emerge with monstrous teeth and the power to destroy. It was probably a relief to both of us that I decided not to visit again.

Eve put a consoling hand on my arm. ‘How are you feeling about it all?’

‘I don’t know.’ It was true.

‘Oh, come on, Iz. It’s me: emotional trainwreck Eve. You don’t have to stay buttoned-up with me.’

‘To be honest, it was a bit of a shock to hear he was dead. The last time I saw him on TV he looked fine. But the money from selling the house will come in handy.’

For a moment she looked appalled. Then she gave me the bright, forced smile you might give a three-year-old that’s just inadvertently (or not) stamped on a frog. ‘You’re probably still feeling a bit numb, from the shock of it all. Some people grasp the enormity of a death at once; it just takes longer with others. The grief will kick in later.’

‘Honestly, Eve, I don’t think so. He walked out of my life when I was fourteen. This wretched letter is the first time he’s been in contact since. How are you supposed to feel about a father who did that to you? No matter how rich he is.’

My father might have ended up as a rich man, but he hadn’t started out that way. Archaeology isn’t an occupation known for making fortunes. He had a genuine passion for the ancient past, having spurned the modern world as a thoroughly bad lot, which was not an entirely surprising attitude for a young man coming of age immediately after the Second World War, with all the horrors and inhumanities that liberation had revealed. When he met my mother on a dig in Egypt in the fifties he barely had the price of a meal. She, however, came of aristocratic French stock, with a smart house in the first Paris arrondissement and a small chateau in the Lot. They travelled together all over the world, from one ancient site to another. They visited the excavated ziggurat at Dur Untash and joined for a while Kelso’s dig at Bethel. They saw the Neolithic plastered skulls unearthed at Jericho and marvelled over the rosered city at Petra. They saw Imhotep’s stepped pyramid and the city of the dead at Saqqara, spent time walking amid the Roman ruins of Volubilis and visiting the ancient capital of the Hoggar at Abalessa. They were, as they loved to tell me, academic nomads, always on the trail of knowledge. And then I came along and put a stop to their joyous quests.

My father got work as a researcher just as the new medium of television was taking off; soon every family in Britain was basing its evening life around its television set. Not long after, he got a lucky break and ended up presenting an hour-long segment when the regular presenter fell ill. He was good at it; he was an immediate hit with the public, with his slightly old-fashioned academic air. He was handsome without being overly distracting, a man whom women enjoyed watching and men would listen to, and infectiously enthusiastic about his favourite subjects. He was the David Attenborough of archaeology: he made history entertaining, and the British have always loved history – they lay claim to so much of it. On the screen he radiated bonhomie and a generous delight in sharing his passion. I remember him on one programme horrifying a British Museum curator by trying on the Sutton Hoo helmet and getting it stuck on the crown of his head. Ancient peoples were smaller than we are today, he spluttered, struggling to wrestle it off, leaving his dark hair standing up in tufts. People loved him for gaffes like this: they made him human and accessible, and by association brought the subjects of his programmes closer to them. It was exceedingly odd to see him still walking and talking on television even after he’d left us, as if nothing had happened. The worst of it was that you never knew where he’d pop up next: he was a public institution, a national treasure. It was easy enough to avoid programmes about history and archaeology, but turn over to watch a charity appeal for some godforsaken corner of Africa and you’d suddenly be caught out as he appeared, running a hand through his increasingly mad hair and making an impassioned plea for funds.

‘Come on,’ Eve said, leaping to her feet and grabbing up her handbag. ‘We’re going to the house.’ She saw my face and added quickly, ‘We can make an assessment in preparation for the sale. Instructions for the agents, stuff to be cleared, that sort of thing. You’re going to have to do it some time or another, so why not now, while I’m here? Bit of moral support, remember?’

I stared past her shoulder into the rain-sodden courtyard, where a pair of cats were squaring up to one another, one on the wall, the other on top of the shed. The one on the shed roof had its ears laid flat to its skull; the tabby on the wall looked ready to spring. I walked quickly to the window and tapped on the glass. Both cats turned to stare at me, their yellow gazes inimical. The cat on the shed stood up and stretched its back legs, then its front legs, and leapt neatly down on to the patio. The tabby started unconcernedly to lick its paws. Humans: what did they know?

Abruptly, I remembered the cat we had owned in my youth – Max, short for Doctor Maximus ibn Arabi, a lithe beast with huge ears and a sleek, sandy-brown coat like a fennec fox – and how he would lie stretched out in my sandpit at the bottom of the garden, blinking at the sun as if he had located himself in a tiny yet infinite desert. At the age of eight I asked my father why our cat had such a strange name. My friends’ cats were called simple descriptive things such as Blackie or Spot or Socks. ‘That’s not even his real name,’ he told me solemnly, as if imparting one of the world’s long-hidden secrets. ‘Nor is he even just a cat. He’s the reincarnation of an ancient scholar and his real name is Abu abd-Allah Muhammad ibn-Ali ibn Muhammad ibn al-Arabi al-Hatimi al-TTaa’i. And that’s why we call him Max.’ Which left me none the wiser. But every time that cat looked at me I sensed it regarded me through the veil of hundreds of years of acquired wisdom. Other children might have been unnerved by such a concept, but I was fascinated. I would lie nose to nose with Max out in the garden to see if that wisdom would leap the gap between us, inter-species. I had completely forgotten not just that cat, but the entire sensation of magic and promise and possibility it had represented to the child I had been.

Remembering now, I felt like an entirely different person to that naive and trusting eight-year-old; but perhaps her shade was waiting to be reunited with me under the eaves of my childhood home. ‘All right,’ I said, making what felt like a momentous decision. ‘Let’s go.’

From the Hardcover edition.

When I was a child, I had a wigwam in our back garden: a circle of thin yellow cotton draped over a bamboo pole and pegged to the lawn. Every time my parents argued, that was where I went. I would lie on my stomach with my fingers in my ears and stare so hard at the red animals printed on its bright decorative border that after a while they began to dance and run, until I wasn’t in the garden any more but out on the plains, wearing a fringed deerskin tunic and feathers in my hair, just like the braves in the films I watched every Saturday morning in the cinema down the road.

Even at an early age I found it preferable to be outside in my little tent rather than inside the house. The tent was my space. It was as large as my imagination, which was infinite. But the house, for all its grandeur and Georgian spaciousness, felt small and suffocating. It was stuffed with things, as well as with my mother and father’s bitterness. They were both archaeologists, my parents: lovers of the past, they had surrounded themselves with boxes of yellowed papers, ancient artefacts, dusty objects; the fragile, friable husks of lost civilizations. I never understood why they decided to have me: even the quietest baby, the most house-trained toddler, the most studious child, would have disrupted the artificial, museum-like calm they had wrapped around themselves. In that house they lived separated from the rest of the world, in a bubble in which dust motes floated silently like the fake snow in a snow-globe. I was not the child to complement such a life, being a wild little creature, loud and messy and unbiddable. I liked to play rough games with the boys instead of engaging in the sedate, codified exchanges of the other girls. I had dolls, but more often than not I beheaded or scalped them, or buried them in the garden and forgot where they were. I had no interest in making fashionable outfits for the oddly attenuated pink plastic mannequins with their insectile torsos and brassy hair that the other girls so worshipped and adorned. I had little interest even in my own clothes: I preferred making mud missiles and catapults and chasing my playmates till my sides hurt from a combination of laughing and stitches, building hides and running around half naked, even in the winter.

‘You little savage!’ my mother would admonish, accompanying the words with a sharp smack on the backside. ‘For God’s sake put some clothes on, Isabelle.’ She would say this with all the severity her clipped French accent could deliver, as if she thought she could imprint civilized behaviour on me by the use of the full version of my old-fashioned name. But it never really worked.

My friends called me Izzy: it fitted the chaos of me, always buzzing, always noisy – such a trial.

In the garden behind our house my friends and I played at being cowboys and Indians, Zulus, King Arthur and Robin Hood, armed with swords and spears in the form of bamboo canes robbed from the vegetable patch, and make-believe bows and arrows. When it came to the Robin Hood game I always insisted on playing a merry man, or even the Sheriff of Nottingham – anything other than Maid Marian. In all the versions of the legend I’d come across Maid Marian didn’t do very much except get imprisoned and/or rescued, which didn’t greatly appeal to me. I had no interest in being the swooning prisoner: I wanted to wrestle and hit people with sticks, like the rough little tomboy I was. This was in the late sixties and early seventies: girlpower hadn’t yet turned Maid Marian, Guinevere, Arwen or any of the other complaisant heroines of legend into feisty, all-action go-getters. Besides, in comparison with the pale, pretty girls who were my friends, I was too ugly to play the heroine. I didn’t care: I liked being ugly. I had thick, black hair and dirty skin and earth under my nails and calluses on my feet, and that was how I preferred it. How I howled when my mother made me take a bath, when she attacked me with Wright’s coal tar soap, or tried to untangle my hair. If guests were staying at the house, as they occasionally did, she had to warn them, ‘Take no notice of the screaming: it’s only Isabelle. She hates having her hair washed.’

You’d never have recognized me three decades later.

The day I went to the solicitor’s office to take charge of the letter my father had left me in his will I wore a classic Armani trouser suit and Prada heels. My unruly hair was cut and straightened into a neat shoulder-length bob; my make-up was discreet and expertly applied. The dirt under my nails had been replaced with a practical square-cut French manicure. Ironic, really: I now presented myself in a manner of which my mother would have thoroughly approved, had she still been alive. It was hard even for me, who had travelled every step of the long path between the grubby little hooligan I had once been and the carefully turned-out businesswoman I had become, to reconcile the two.

The letter he left for me was short and cryptic, which was apposite: my father was a short and cryptic sort of man. It said:

My dear Isabelle

I know I have been a great disappointment to you, as a father and as a man. I do not ask for forgiveness, or even understanding. What I did was wrong: I knew it then, and I know it now. One bad decision leads to another and another and another; a chain of events leading to catastrophe. There is a story behind this catastrophe to be told, but I am not the one to tell it. It is something you need to piece together for yourself, for it belongs to you and I do not want to reinterpret it for you, or to spoil it as I have spoiled everything else. So I am leaving you the house: and something else besides. In the attic you will find a box with your name on it. Inside that box are what you might call ‘waymarkers’ for your life. I know you have always felt at odds with the world in which you found yourself, and I must take at least half of the blame for that; but perhaps by now you have come to terms with it. If that is indeed the case, forget this letter. Do not open the box. Sell the house and everything in it. Let sleeping beasts lie. Go in peace, Isabelle, and with my love. For the little it is worth.

Anthony Treslove-Fawcett

I read this in the lawyer’s office in Holborn, a brisk ten-minute walk away from the office where I worked as a highly paid tax accountant, with the solicitor and his clerk watching on curiously. Also in the envelope, a set of house keys on a battered leather fob.

‘All well?’ the solicitor asked brightly. A strange question to ask someone whose father has just died; though maybe he was not to know that I had not seen that father in the best part of thirty years; not in person, at least.

I was shaking so much I could hardly speak. ‘Yes, thank you,’ I replied, stowing the letter and keys clumsily into my handbag. Summoning every ounce of resolve, I gave him a smile so bright it would have dazzled blind Justice herself.

The senior partner tried not to show his disappointment at my failure to disclose the contents. Then he passed me a folder of papers and started to talk very fast.

All I wanted was to be outside now. I needed sunlight on me; I needed outdoor space. I could feel the walls of the office – its stacked shelves and massive filing cabinets – closing in on me. The words ‘probate’ and ‘frozen accounts’ and ‘legal process’ came at me thick and fast, a maddening buzz of flies in the back of my skull. While he was still in mid-sentence, I wrenched open the door, stepped out into the corridor and fled down the stairs.

When my father left us, I was fourteen. I had not cried, not one tear. I had mixed feelings about his absence: I hated him for walking out, despised him for running away and abandoning us; but from time to time I suffered flashes of mourning for the father he had occasionally shown himself to be and also felt a considerable relief that he was not there any more. It made life easier, if colder and poorer. My mother did not show the distress his disappearance must have caused her. She was not a demonstrative woman, my mother, and I didn’t understand her: she remained a mystery to me throughout my life. My father, with his volcanic temper and choleric disposition, seemed more like me; but my mother was a perfect Ice Queen, chilly and polite, interested only in the outward face one turned to the world. When it came to child-rearing she made it her business to monitor my progress at school, my appearance, my manners. She found emotional display vulgar, and I must have been a terrible disappointment to her with my exuberance and rages. She treated me with a sort of cool impatience, a repressed exasperation, forever repeating her corrections and strictures as if I were an espaliered pear tree that constantly needed lopping in order to make it grow along the correct lines. For most of my life I thought all mothers were like this.

But one day when I returned from school there was something different in the atmosphere of the house, something charged and threatening, as if an electric storm was lurking inside. I found my mother sitting in the half-dark with the curtains drawn. ‘Are you OK?’ I asked, scared suddenly by the idea of losing a second parent.

I pulled the curtains back and the harsh late-afternoon sunlight obliterated her features, making her face a flat white Kabuki mask, turning her into a foreign, disturbing presence. For a moment this faceless woman sat staring at me as if I were a stranger. Then at last she said, ‘Everything was wonderful between us until you came along. I knew you would ruin everything from the first moment I held you in my hands.’ She paused. ‘Sometimes you just know these things. I told him that I never wanted children; but he was so determined.’ She fixed me with her dark eyes and I was appalled by the quiet malevolence I glimpsed there.

Long moments passed and I felt my heart beating wildly. Then she smiled at me and started to talk about the rhododendrons in the garden.

The next day she was just the same as usual. She clicked her tongue over the state of my uniform (I had fallen asleep in it and it was crumpled and ruined) and tried to make me take it off so that she could iron it, but I was out of the door quickly. From that day on I lived as if I were walking across the surface of a frozen lake, terrified that the fragile, apparent surface might at any moment give way, plunging me into the roiling darkness I had glimpsed beneath. Of course, no one else knew about our strange and strained relationship: who was there to tell, and what was there to say? Abandoned by one parent, afraid of another sudden glimpse of the terrifying void inside the other, I realized I was on my own; and so as the years rolled on I devoted myself to being self-sufficient, not just in terms of financial means but in all the ways that matter, sealing myself off from need and desire and pain, making a bubble around myself that no one could penetrate.

But that evening at my kitchen table when I reread the letter I knew that bubble was about to be shattered.

Forget this letter. Do not open the box. Sell the house and everything in it. Let sleeping beasts lie . . .

Was there ever a farewell letter so guaranteed to torment? Whatever did he mean by ‘sleeping beasts’? The phrase plagued me. It also filled me with a mysterious, deep-seated excitement. My life had been so settled, so dull, for so long: but I sensed that something was about to change.

At the gym the next morning I determinedly ran and stepped and skied and pulled weights for an hour. I showered, dressed in Chanel and arrived at my office at precisely ten minutes before nine, as I did every working day. There, I switched on the computer, examined my calendar and made a list of the day’s tasks, allotting times and precedence to each of them.

I had sought security in all aspects of my life, and as Benjamin Franklin’s old saw goes, there is nothing sure in life but death and taxes. Not much fancying the trade of an undertaker, I had opted for the latter. As a corporate tax accountant my working life ran in a smooth routine from day to day. Most nights I’d leave the office at half past six, catch the tube and train home, put together a simple meal and read a book, watch the news on television and go to bed, alone, before eleven. Occasionally, I’d go into town and meet a friend; or a stranger. Sometimes I went to the indoor wall at the Westway or the Castle and climbed like a demon: my one concession to the lost Izzy trapped within. And that was my life.

I kept no ties to the girl I had been. Except for Eve.

I had known Eve since I was thirteen and she had moved into the area with her father. Eve was everything I was not: pretty, funny and more sophisticated than the rest of us, who were busy with trying to stick safety pins in our ears and join, rather belatedly, the punk revolution. Eve wore authentic Westwood bondage trousers and ripped T-shirts tied artfully at the waist; with all this and her dandelion-blonde hair she looked like Debbie Harry. Everyone loved Eve, but for some reason it was me she chose as her friend, and it was Eve I turned to that first Saturday morning after taking receipt of my father’s bombshell of a letter.

‘Come over,’ I said. ‘I need some moral support.’

At the other end of the phone, her laugh rang out. ‘You hardly need me for that! Give me half an hour, I’ll be over for some immoral support. Much more fun.’

She’d come to the funeral with me, and cried till her eyes were red, while I remained stone-faced throughout. Everyone who didn’t know me had thought she was Anthony’s daughter. ‘He was nice, your dad,’ she said now, turning her coffee cup around in her hands. ‘Remember when Tim Fleming broke my heart?’

Tim Fleming had been seventeen to our thirteen, louche, long-haired and leather-jacketed. Going out with him was just asking for trouble, which was exactly what Eve wanted, and got. I grinned. ‘Who could forget?’

‘Your father gave me that look of his – you know’ – she put her head on one side and fixed me with a beady eye; it was an absurd exaggeration of his most quizzical expression but strangely accurate – ‘and said: “Pretty girl like you, you’re wasted on a git like that.” It was so funny, a word like that being said in that incredibly posh accent of his: I just burst out laughing. And that’s what I told him myself when I saw him next, remember? “I’m wasted on a git like you!”’

I remembered Eve striding up to Tim Fleming outside the kebab shop, where he was mooching around that Saturday lunchtime with the rest of his friends, and shouting the words out, her blonde hair flying like a banner. She’d seemed so bright and defiant, and I was so proud of her. Hers was not the image of my father I most often remembered, though.

She read my father’s letter, frowning in concentration, then read it again. ‘Weird,’ she said at last and handed it back to me. ‘A box in an attic, eh? Do you think your mother’s corpse is in it, mouldering away? Perhaps she never died in France at all.’ She made a Gothic face at me. The eyeliner beneath her left eye had smudged. I itched to reach over and wipe it away, not out of any lesbian urge but purely for the sake of tidiness.

‘Oh, she went back to France, all right.’

As soon as I left to go to university, as if abnegated of all responsibility for me, my mother had sold her share of the house back to my father for some astronomical sum (I had not realized they were even in contact) and gone back to France. I visited her there twice before she died; and each time she was as distant and polite as a passing acquaintance. Each time I sensed dark shadows gliding beneath the composed exterior, and knew that if those shadows were to surface they would emerge with monstrous teeth and the power to destroy. It was probably a relief to both of us that I decided not to visit again.

Eve put a consoling hand on my arm. ‘How are you feeling about it all?’

‘I don’t know.’ It was true.

‘Oh, come on, Iz. It’s me: emotional trainwreck Eve. You don’t have to stay buttoned-up with me.’

‘To be honest, it was a bit of a shock to hear he was dead. The last time I saw him on TV he looked fine. But the money from selling the house will come in handy.’

For a moment she looked appalled. Then she gave me the bright, forced smile you might give a three-year-old that’s just inadvertently (or not) stamped on a frog. ‘You’re probably still feeling a bit numb, from the shock of it all. Some people grasp the enormity of a death at once; it just takes longer with others. The grief will kick in later.’

‘Honestly, Eve, I don’t think so. He walked out of my life when I was fourteen. This wretched letter is the first time he’s been in contact since. How are you supposed to feel about a father who did that to you? No matter how rich he is.’

My father might have ended up as a rich man, but he hadn’t started out that way. Archaeology isn’t an occupation known for making fortunes. He had a genuine passion for the ancient past, having spurned the modern world as a thoroughly bad lot, which was not an entirely surprising attitude for a young man coming of age immediately after the Second World War, with all the horrors and inhumanities that liberation had revealed. When he met my mother on a dig in Egypt in the fifties he barely had the price of a meal. She, however, came of aristocratic French stock, with a smart house in the first Paris arrondissement and a small chateau in the Lot. They travelled together all over the world, from one ancient site to another. They visited the excavated ziggurat at Dur Untash and joined for a while Kelso’s dig at Bethel. They saw the Neolithic plastered skulls unearthed at Jericho and marvelled over the rosered city at Petra. They saw Imhotep’s stepped pyramid and the city of the dead at Saqqara, spent time walking amid the Roman ruins of Volubilis and visiting the ancient capital of the Hoggar at Abalessa. They were, as they loved to tell me, academic nomads, always on the trail of knowledge. And then I came along and put a stop to their joyous quests.

My father got work as a researcher just as the new medium of television was taking off; soon every family in Britain was basing its evening life around its television set. Not long after, he got a lucky break and ended up presenting an hour-long segment when the regular presenter fell ill. He was good at it; he was an immediate hit with the public, with his slightly old-fashioned academic air. He was handsome without being overly distracting, a man whom women enjoyed watching and men would listen to, and infectiously enthusiastic about his favourite subjects. He was the David Attenborough of archaeology: he made history entertaining, and the British have always loved history – they lay claim to so much of it. On the screen he radiated bonhomie and a generous delight in sharing his passion. I remember him on one programme horrifying a British Museum curator by trying on the Sutton Hoo helmet and getting it stuck on the crown of his head. Ancient peoples were smaller than we are today, he spluttered, struggling to wrestle it off, leaving his dark hair standing up in tufts. People loved him for gaffes like this: they made him human and accessible, and by association brought the subjects of his programmes closer to them. It was exceedingly odd to see him still walking and talking on television even after he’d left us, as if nothing had happened. The worst of it was that you never knew where he’d pop up next: he was a public institution, a national treasure. It was easy enough to avoid programmes about history and archaeology, but turn over to watch a charity appeal for some godforsaken corner of Africa and you’d suddenly be caught out as he appeared, running a hand through his increasingly mad hair and making an impassioned plea for funds.

‘Come on,’ Eve said, leaping to her feet and grabbing up her handbag. ‘We’re going to the house.’ She saw my face and added quickly, ‘We can make an assessment in preparation for the sale. Instructions for the agents, stuff to be cleared, that sort of thing. You’re going to have to do it some time or another, so why not now, while I’m here? Bit of moral support, remember?’

I stared past her shoulder into the rain-sodden courtyard, where a pair of cats were squaring up to one another, one on the wall, the other on top of the shed. The one on the shed roof had its ears laid flat to its skull; the tabby on the wall looked ready to spring. I walked quickly to the window and tapped on the glass. Both cats turned to stare at me, their yellow gazes inimical. The cat on the shed stood up and stretched its back legs, then its front legs, and leapt neatly down on to the patio. The tabby started unconcernedly to lick its paws. Humans: what did they know?

Abruptly, I remembered the cat we had owned in my youth – Max, short for Doctor Maximus ibn Arabi, a lithe beast with huge ears and a sleek, sandy-brown coat like a fennec fox – and how he would lie stretched out in my sandpit at the bottom of the garden, blinking at the sun as if he had located himself in a tiny yet infinite desert. At the age of eight I asked my father why our cat had such a strange name. My friends’ cats were called simple descriptive things such as Blackie or Spot or Socks. ‘That’s not even his real name,’ he told me solemnly, as if imparting one of the world’s long-hidden secrets. ‘Nor is he even just a cat. He’s the reincarnation of an ancient scholar and his real name is Abu abd-Allah Muhammad ibn-Ali ibn Muhammad ibn al-Arabi al-Hatimi al-TTaa’i. And that’s why we call him Max.’ Which left me none the wiser. But every time that cat looked at me I sensed it regarded me through the veil of hundreds of years of acquired wisdom. Other children might have been unnerved by such a concept, but I was fascinated. I would lie nose to nose with Max out in the garden to see if that wisdom would leap the gap between us, inter-species. I had completely forgotten not just that cat, but the entire sensation of magic and promise and possibility it had represented to the child I had been.

Remembering now, I felt like an entirely different person to that naive and trusting eight-year-old; but perhaps her shade was waiting to be reunited with me under the eaves of my childhood home. ‘All right,’ I said, making what felt like a momentous decision. ‘Let’s go.’

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Jane Johnson has written a beautifully crafted story that paints a vivid picture and captures the imagination. . . . [The] reader can see the colours of sunsets, feel the grittiness of the sand, taste the spices in the bazaar and smell the camel hair blankets in the goatskin tents. . . . The Salt Road is a book you won’t want to end, yet at the same time, you’ll be yearning for a satisfying conclusion. [This] novel will not let you down.”

— Liz Read, The Women’s Post

“The Salt Road, like all powerful stories, is about change. . . . For readers looking to experience a shifting, disappearing world, and to be introduced to an exotic culture with evocative descriptions, The Salt Road is an exhilarating ride. Part historic and part contemporary, with universal themes of betrayal, love, and the anguish caused by human greed, it has an ending rich and fulfilling enough for those who like all their questions answered.”

—Linda Holeman, The Globe and Mail

“Jane Johnson (The Tenth Gift) re-works her irresistible cross-cultural magic . . . in The Salt Road”

—More magazine

From the Hardcover edition.

— Liz Read, The Women’s Post

“The Salt Road, like all powerful stories, is about change. . . . For readers looking to experience a shifting, disappearing world, and to be introduced to an exotic culture with evocative descriptions, The Salt Road is an exhilarating ride. Part historic and part contemporary, with universal themes of betrayal, love, and the anguish caused by human greed, it has an ending rich and fulfilling enough for those who like all their questions answered.”

—Linda Holeman, The Globe and Mail

“Jane Johnson (The Tenth Gift) re-works her irresistible cross-cultural magic . . . in The Salt Road”

—More magazine

From the Hardcover edition.

Caracteristici

Author is from the UK but spends half the year living in Morocco.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

A magical historical adventure which brings the most unlikely of people together in an epic quest that spans the decades and the hot, shifting sands of Morocco.