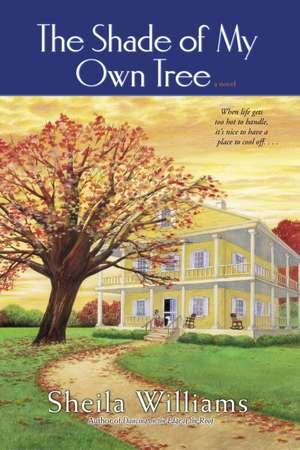

The Shade of My Own Tree

Autor Shelia Williams, Sheila Williamsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2003

The courage to change doesn’t come easy. When Opal Sullivan walks out on an abusive husband after fifteen years, she has only her dreams in her pocket. Her new beginning starts in Appalachian River country, where she sees a bit of herself in a graceful but dilapidated house. Like Opal, the house is worn-out and somewhat beaten up, but it still stands proudly and deserves a second chance.

So Opal opens her doors—and her heart—to a parade of unforgettable characters. There’s sassy Bette Smith with her cantaloupe-colored hair and four-inch heels; short-tempered Gloria and her devilish son, Troy; the mysterious Dana, who dresses in black and keeps exclusively nocturnal hours; a dog named “Bear” who is afraid of his own shadow; and Jack, who doesn’t mind hanging out with an OBBWA (old black broad with an attitude). It is Jack who helps Opal understand a funny thing about life: You can’t move forward if you keep looking back. . . .

Preț: 121.22 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 182

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.20€ • 25.21$ • 19.50£

23.20€ • 25.21$ • 19.50£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345465177

ISBN-10: 0345465172

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 142 x 208 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: One World/Ballantine

ISBN-10: 0345465172

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 142 x 208 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: One World/Ballantine

Extras

Chapter One

I sit in the shade of my own tree now, but it wasn’t too long ago, I didn’t have a twig, much less a tree to sit under. I was running from a marriage that was no good. It took me fifteen years to take that first step, but once I did, I just kept going. Now, several years have come and gone. Already! Time flies when you’re having fun. Or running for your life.

I married my college boyfriend, Ted, when I was twenty-one.

After a few years of marriage, I knew that I had made a terrible mistake.

But once I was in, I didn’t know how to get out. It was like being in prison. And I had a life sentence with no chance of parole.

I got three squares a day and had a bed, but that was it. There was hard labor and solitary confinement if I was uncooperative. Or if, as in Ted’s words, I acted like a “sassy, smart-mouth bitch.”

Even when it got as hot as hell in the summer, I wore long sleeves. My arms were always bruised. One August, I wore turtleneck sweaters to work for two weeks until the marks of Ted’s handprints faded where he had tried to choke me.

I know what you’re thinking: She sounds so articulate! She could get a job anywhere. Why didn’t she just leave? Why did she stay and put up with that?

How many times have I asked myself those questions? How many times did I beat myself up after Ted beat me up? I’ll turn the tables on you. You don’t understand what I was dealing with. And for years, I didn’t understand, either. By the time I did, it was almost too late.

The slaps, pushes, kicks, and punches didn’t start right away of course. The insults, put-downs, scoldings, and verbal abuse began slowly. He started with “constructive criticism.” I knew that I was in for it when he said, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but . . .” or, “This is for your own good.” By the time he finished with me, I felt like I was six inches tall and three years old, standing in the corner for bad behavior.

Ted was charming in college. Smart and handsome, athletic and talented, he played a saxophone that Sonny Rollins would have been jealous of. Everyone loved Ted. Especially women. The cutest girls on campus threw themselves at him. I, on the other hand, was awkward and strange. I liked Bach, the Indian-influenced music of Alice Coltrane, Herbert Marcuse, and Jane Eyre. Ted could dance. I had two right feet and that is worse than two left ones. Ted talked and dressed “cool.” I didn’t.

So when Ted Hearn asked the tall, gangly, studious-looking redbone girl from Ohio with straw-colored hair, braces, and glasses with lenses thicker than bullet-proof glass for a date, everyone was shocked. Especially me. I had never had a boyfriend like Ted before. I was thrilled and proud to be seen with him. I was finally “cool.” Ted took care of everything. He was wonderful. He made sure that my friends didn’t take advantage of my weakness for loaning out books and albums and helping with term papers. He helped me deal with my mother, who had a tendency to be a little overbearing and critical. Ted helped me with my class schedules; he even started to suggest the subjects for the paintings that I did, because I thought that I was a painter. He was so protective of me. At least, that’s what I thought at the time.

By the time we got married, the trap was nearly set. I was already isolated from my friends, who had been cut out of my life by Ted, who wanted only to be with me. He had alienated me from my mother, and my poor easygoing father accepted without question what he interpreted as a natural transition of authority: from father to husband.

Two weeks after our honeymoon, Ted and I moved to Atlanta, where he had taken a job. I was now three states and fourteen hours away from home. I had a new house, a car of my own (that was in Ted’s name), and a part-time job. I was pregnant and I didn’t know anybody in the big, long state of Georgia, not one soul. By the time our daughter, Imani, was born, the cheese was in the trap.

It started with an argument, I think. I don’t remember now what the argument was about. It ended with Ted backhanding me and then apologizing. It happened so fast. And then we made love. And it didn’t happen again for six months. I remember saying to myself, Maybe I imagined that. Maybe it didn’t really happen.

But, of course, it happened again. A push and a shove into the stove. Dinner was late that night. It was early the next night and I was slapped because it was cold. This was before microwaves.

I thought about calling for help. But who was I going to call? Imani? My friends? I didn’t have any friends. The only people I knew were the people Ted knew. And he was very careful to make sure that I didn’t get too friendly with anyone. I couldn’t call my parents, either. In my family, whining is not allowed. Thanks to Ted, Mother and I were barely speaking. And Dad’s gentle nature hid a strong resolve when it came to working out your own issues in a marriage. “If you make your bed too hard,” he always said, “be ready to turn over more often.” I turned over and over and over.

So I did nothing. The years of my life flew by.

Unlike prison, there was never time off for good behavior, because Ted beat me whether I was “good” or not. What was “good”? He made me feel small.

As the years passed, I became numb. I did not feel at all. The only thing that made me smile was Imani, our daughter. And yet there were days when, even with her, I couldn’t remember how. My voice grew softer and quieter and then went silent. I nearly disappeared altogether. Except when I screamed. I had volume control. There was loud. And there was louder. When Ted told me to shut up, I bit through my bottom lip and sent the screams deep inside.

I saw a silly movie once about voodoo and zombies. I watched the campy-looking zombie stagger through the scenes with its black-circled eyes and a blank expression. I could have performed that role myself without makeup, script, or rehearsal. Ted had beaten the humanity out of me.

I did ask for help a few times when I could get up the courage and get past the humiliation.

I just didn’t take the advice that I got.

I called a domestic violence hot line. The woman told me to pack up my daughter and leave Ted. Right then. Take only my purse and my keys. They had a shelter on Peachtree. Leave Ted and do what? I was only working part-time then. Imani was six. What would I do for money? Where would I live? How would I live?

Another time, after we moved north, a hospital social worker visited me, uninvited. I had been kept overnight for observation after Ted kicked me in the abdomen and broke a couple of my ribs. She touched one of the dark red roses that Ted had sent me from an expensive florist. I know that she saw the card that read: “I don’t know what got into me. I love you so much. I would die if you left me. Ted”

The woman sat down in the chair next to my bed and looked me straight in the eye. She didn’t say good morning; she didn’t say, “How are you feeling?” She just looked at me without smiling.

“If you don’t leave him, you will die.”

And then, there was the memorable occasion that I talked with Miss Thelma, one of the elders at my church. She clucked her tongue at me.

“Honey, there ain’t no problem with that man. Now he’s got a good job at the auto plant and he brings home good money. You-all have that nice house over there on the east side and you got your own car. You ain’t got nothin’ to complain about. What’s the matter with you?”

Well, that was no advice at all.

I was afraid to leave Ted. And I was afraid to stay.

I left him four times. And I came back four times. I called the police so often that they knew me by my first name: “Opal, are you going to let us lock him up?”

And I did a few times.

Ted called me from jail: “Are you gonna come and get me out? I’ll kick your ass if you don’t.” Ted wasn’t charming anymore.

I pretty much lost everything.

The few friends I’d made stopped calling because I always canceled lunch and girls’ night out at the last minute. And I wouldn’t return their telephone calls. I didn’t want to hear what they were telling me.

I missed the sermons and the music at church that gave me so much comfort. I stopped going to church because I dropped out of the choir. And I dropped out of the choir because I missed too many rehearsals. I missed too many rehearsals because I was ashamed. I didn’t want God to see my black eyes, bruises, and swollen lips. I didn’t want him to know.

Except for work and the grocery store, I became a recluse. I hardly saw anyone. I learned, well, sort of, what set Ted off. I could walk on eggshells in high heels. I was good. I could sense an electricity in the air; I could tell from the set of his jaw or the look in his eye. Sometimes I could tell whether I was going to be slapped or kicked. Or both. I should have used that ESP on better things.

It’s true that you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. I call it the ruby slippers syndrome: you can wear those shoes all over the place, but until you click your heels together and chant the magic words, nothing will happen.

I eventually made up with my mother and my parents offered me sanctuary. They knew what was going on. But I wouldn’t take it.

My brother, JT, threatened to just show up one day with a U-Haul to take me, Imani, and all of our furniture and other belongings away. I refused to go.

Even my cats left. There was a time, some years ago, when Ted would come home after he’d been drinking and pick up one of them and throw him against the wall to see if cats would bounce.

They don’t.

You don’t have to tell cats anything twice.

By the time Imani was ten, she knew that her mommy and daddy weren’t like other mommies and daddies or like the ones that she saw on TV. The households of her friends may have been noisy and hectic, but the muffled sounds of shrieks, screams, and banging furniture were absent. The mothers of her girlfriends didn’t have bruises or black eyes. My daughter is a smart kid. She never brought her friends home with her.

And I was stupid and blind enough to believe that because Imani was a child, she didn’t notice what was happening in her home.

“Mommy, did Daddy hurt you?”

Imani asked this question again and again over the years until it became more of a statement than an inquiry.

“No,” I lied. “Daddy was just a little upset.” My eyes were puffy because Daddy was “a little upset.” The kitchen chair was a pile of sticks because Daddy was “a little upset.”

Who was I kidding?

Certainly not my daughter. I became a “shadow” mommy, there but not there, lurking around the edges of my daughter’s life.

Imani left for college when she was eighteen, and she hasn’t really been home since. She spent the holidays with my parents. Ted got worse after she left. Once she was gone, there was no more need for me to bite my lip to keep from screaming. There was no one to hear.

And still, I stayed.

I must have been waiting for a sign from God. It fi- nally came.

Ted and I went to Kmart. I think we were looking for a lawn mower or some yard tools or something, I don’t really remember now what it was. We didn’t find the lawn mower, but we picked up a few other things, moved at a snail’s pace through the checkout line, then headed home.

Ted was quiet in the car.

I knew then.

The automatic garage door hadn’t finished its descent before he started in on me.

“Think you’re pretty slick, don’t you?”

My stomach began to churn.

“Ted, what are you talking about?”

His voice got louder and he clenched and unclenched his fists.

“I saw you looking at that man in the white shirt. I saw him looking at you! Who is he?”

The first punch caught me on the back of my head. The second one grazed my right eye. I saw stars and dropped to the floor.

“What man?”

“Bitch! I am tired of this shit! Do you think that you can sneak around on me!”

He kicked me in the ribs and in the stomach. My head was ringing and I remember thinking that now I knew how a football felt. A stupid thought, really, when you’re being beaten. But my mind was desperately trying to separate itself from the pain and the fear. I tried to open my eyes and look at Ted as I defended myself. But my left eye was bleary from the tears. And my right eye was swollen shut.

“I don’t know who—”

“You’re my goddamn wife and don’t you forget it!” he bellowed as he dragged me up from the floor by the collar of my shirt. “I’ll take care of this shit right now!”

He threw me against the wall and stormed off into the family room. I thought for a moment that he was going to get a gun and shoot me, but Ted doesn’t have a gun. His fists and feet have always been lethal-enough weapons. I just pressed against the wall where he had thrown me, stuck there like a piece of gum. My legs were so wobbly that I could barely stand up. And my vision was so blurred that I couldn’t see to run.

But I saw him approaching, his form dark and ominous. In his hand was a lighted cigarette.

“I’ll take care of this right now,” he repeated. “Your lover boy will know that you’re my wife. And you, you stupid bitch, you’ll know, too.”

He burned me in three places with that cigarette.

Ted left me in a heap on the floor of the foyer whimpering and moaning, my right eye cut and bleeding, my ribs sore, my kidneys bruised, and my arm and neck burned from the small glowing tip of a cigarette.

He went out to meet some friends for drinks at a sports bar.

I didn’t leave him that night.

I didn’t even leave him the next night.

To this day, I don’t remember a white-shirted man in Kmart who gave a hippy, tired-looking middle-aged woman the eye.

I slept in the same bed with Ted for two more nights.

On the third night, the straw broke the camel’s back.

I was brushing my teeth.

It was late and Ted wasn’t home yet. I was tired and had to work the next day, but I knew that I would probably be up all night because he would come home drunk and we would fight about God knows what. I turned off the faucet and caught a glimpse of the woman in the mirror.

I didn’t know who she was.

I hadn’t studied myself in the mirror for years. I usually did just enough to get my hair combed and put my glasses on straight.

My hair was white at the temples and there were pouches under my eyes. My right eye was a mess, completely black-and-blue and still huge. My nose was crooked (it had been broken twice) and there were deep gorges in my cheeks like the Grand Canyon. My complexion was gray. There was a welt on my neck that was several weeks old, but it wasn’t healing right. I’d have an ugly scar there no matter what I did.

And there were small circular sores on my arm and neck where Ted had burned me with the cigarette. I had been putting salve on them, but they still looked raw and nasty.

I looked like an old crack head.

I stared at that woman for a long time. And she stared back with sad, tired eyes.

My mind was confused. The Opal that it remembered was a caramel-colored woman with hair the same color and brown eyes. It remembered a woman with dimples in her cheeks when she smiled and a pointed nose and a little more meat on her bones. Where was the woman who liked fusion jazz, Latin American literature, and Egyptian mythology? The one who dreamed of studying art in Paris and living in a loft? What happened to the Opal who wanted to wear a beret on top of her Afro and find out what was so great about Whistler’s Mother?

“What is this shit?” Ted would ask, looking over my shoulder when I was painting. When he was sober and mean (as opposed to being drunk and mean) he said nothing at all. I’m not sure which was worse.

When Ted began to take out his frustrations on my canvasses, I only painted when he wasn’t home, hiding the pieces in the basement behind the furnace. I pulled them out once a week, then once a month, and then I stopped pulling them out at all. As I looked into the eyes of the defeated-looking woman in the mirror, I realized that I hadn’t looked at those canvasses in over ten years.

Hey! Didn’t you used to be Opal Sullivan? Didn’t you used to be her?

I didn’t know the woman in the mirror and I wasn’t sure that I wanted to. She was the scariest thing I’d seen in years. And she was me.

Then I noticed the ugly red burn on my upper arm.

Over the past fifteen or so years, I had been punched, slapped, backhanded, beaten with a belt, and kicked. I had been belittled and ridiculed. I had been “restrained” (a polite word to use when you have been locked in a closet) and almost choked. I had been smacked and pinched.

But I had never been branded.

And that’s just what Ted had done. He had branded me just like they used to brand slaves.

What was next? Would he stick pins in my feet? Tie me down and put wet bamboo sticks under my fingernails? Would he kill me?

The woman inside me had an answer to that question. The social worker’s words came back: “If you don’t leave him, you will die.”

Ted had his own litany: “If you try to leave me, bitch, I’ll fucking kill you.”

Well, maybe he would and maybe he wouldn’t. I might end up dead.

But I’d be free.

The woman in the mirror was so angry that her face almost split open.

I would be a lot of things in this life, but I would be damned in hell if I’d be branded like a steer.

I left with the clothes on my back and my purse.

I wasn’t sure what to do next.

My parents lived in Florida, and Pam, the only friend I had left that Ted hadn’t run off, was out of town. I was too embarrassed to call anyone else or go to a neighbor’s. With shaking fingers I leafed through the phone book until I found the number that I was looking for.

“Women’s Crisis Center, LaDonna speaking.”

“I, uh . . . I need a place to stay. Just for a few days.”

LaDonna’s voice was calm. “What’s your name, dear?”

“O-Opal Hearn.”

“Are you in a public place, Opal?” she asked.

I told her that I was.

“Is he around?”

“No, no, he’s gone. I’m in my car. At a gas station.”

“Good. You have transportation. All right, here’s what I want you to do. . . .”

The directions were crystal clear. I parked in the small lot behind the innocuous-looking apartment building. A woman holding a flashlight stood in the middle of the lot. She waved me over like she was directing an airplane on landing.

“I’m LaDonna,” she said, smiling. “Come on; let’s get you settled.”

She was petite and wore her waist-length bleached blond hair teased up in a style that I hadn’t even seen on a country and western singer in twenty years. At least two layers of makeup covered her fifty-plus-year-old face. She was dressed in blue jeans, cowboy boots, and a fringed Western-style shirt. Her earrings were almost as big as she was. She looked like Dale Evans on acid. But LaDonna wasn’t singing “Happy Trails.” There was a no-nonsense tone in her voice. This was a woman who was used to giving orders and having them obeyed. A small frown darkened her features. She touched my chin gently and turned my face to the side.

“Has anyone looked at your eye?”

I could barely talk. I shook my head.

She smiled sympathetically and passed me a handful of tissues.

“We’ll take care of it,” she said confidently. She took me by the arm and led me toward a taupe-colored door that was discreetly set in the recessed entryway. “You don’t want to go blind in that eye.”

“Opal R. . . . what’s the R stand for?” LaDonna asked as she filled out a form.

“Renee,” I told her, still blowing my nose.

“Nice name,” she commented. “Just sign here.”

I scribbled something that looked like my signature.

“I’m going to recommend that you not go to work tomorrow. You need a thorough medical exam. I’ll ask Christine, that’s the nurse-practitioner, to look at your eye tonight. But you should see a doctor just to make sure it’s nothing serious,” LaDonna said. “I’ll call your supervisor in the morning and—”

“No!” I shouted, suddenly getting my voice back. “No! Please . . . I’ll . . . I’ll just call in . . . sick or take a vacation day or something.” A lump was forming in my throat. I started crying again. “I—I don’t want them to know. . . .”

LaDonna’s expression was warm, but her words were as sharp as razor blades: “Opal, they know already.”

The humiliation and embarrassment swept over me like a tidal wave.

Of course they knew. I have had black eyes and bruises that paint and plaster couldn’t cover up. I wanted to crawl under LaDonna’s desk and hide.

She smiled and patted me on the arm. “It’s a form of denial, Opal; we’ve all been through it. It’s the work-ethic shit. We are raised from the cradle to get over it. Suck it up! Ignore it,” she said matter-of-factly. “The son of a bitch that I was married to was six feet, five inches tall and weighed over three hundred pounds. I’m barely five feet tall and weigh one hundred pounds. He threw me against a wall once and cracked my pelvis. I went to work the next day with a cane telling everyone that I was hav- ing trouble with my arthritis! Who was I kidding? Only myself.”

My ribs hurt when I laughed. So I cried instead.

Christine’s fingers were cool and firm. Her blue eyes were nearly unblinking as she listened to my heart and probed my abdomen and back.

“Does this hurt? This?”

I shook my head.

“Let me have a look at that eye again.” She turned her head slightly to the left as she studied me. “Good. I don’t think anything is broken. Bruised ribs, that’s all. I want a specialist to check out your eye, though.” She wrote something on a notepad, tore off the top sheet, and handed it to me. “Here’s the name of an ophthalmologist. She’ll see you without an appointment; just tell her receptionist that you’re a client of the Center.”

“OK,” I said. “Thank you.”

“No problem,” the nurse replied. “Just be sure that you go see the doctor. You can’t take black eyes for granted. I should know. The last one I got nearly blinded me. I’ll never be able to see more than shadows out of my right eye.”

I must have gasped, because the nurse smiled at me and folded her arms across her chest.

“I know. I don’t look like ‘the type.’ ” Christine sighed dramatically, then flashed me an impish grin. “I get that a lot. But there are all types, Opal, and that’s what you have to understand. This can happen to anyone. Unfortunately, our society has insulated itself with an antiquated image of a battering husband. They don’t all wear T-shirts and dirty blue jeans and guzzle beer all day. They are mayors, ministers, corporate types, and teachers. They are policemen, believe it or not. They are your coworkers and your funeral director. They are everywhere.” She bandaged my forehead.

“My boyfriend was a medical student. He came from a ‘nice home,’ whatever that is. And went to ‘nice schools’ and lived in an ‘upscale neighborhood.’ ” She paused for a moment and looked at me.

I noticed then that one of her eyes didn’t move in sync with the other one.

“He was so ‘nice’ that he tortured cats and squirrels when he was a kid. I found out later that he had punched his prom date and broke her jaw when he was seventeen. When he grew up, he graduated from small animals and prom dates to girlfriends.” She smirked. “And I wanted to be a doctor’s wife. Can you imagine?” Then she gave me an engaging grin. “After I spent two weeks in the hospital after he tried to kill me because I was leaving him, I decided that I would rather be a doctor myself. I’m going to medical school in the fall.”

LaDonna settled me into a small room with three beds.

“We’re under capacity tonight, so you’ll be on your own. The room across the hall and the room next to yours are occupied, but I don’t think you’ll be disturbed. Oh, and just ignore any clanging you hear from the basement. We had a broken pipe scare and the maintenance man is finishing up down there.”

She set an extra pillow on the bed and patted me on the shoulder.

“Sleep well, Opal. You’re safe now.”

...

I sat in the corner of the TV room by myself.

The woman in the room next to mine walked in on bare feet and got a Coke out of the vending machine. She nodded at me and padded out. I heard the maintenance man coming up the basement steps with the gait of King Kong. The basement door creaked when it closed and he clomped down the hall and stepped into the TV room, setting his toolbox on the floor. He, too, went to the vending machine to get a can of soda.

“Oh! Excuse me; I didn’t know that anyone was in here,” he said apologetically when he noticed me.

I turned my face away from his and scooted the chair quickly into a shadow. I wasn’t ready to face anyone else with a fat lip and one eye that was swollen and multi- colored.

“It’s OK,” I told him. “I was just sitting here.”

He paused for a moment. “Do you want me to turn on more lights for you?”

I shook my head. “No, thank you.”

“Then I’ll let you get back to it,” he said, giving me a nod and a quick smile. He had a nice face. And then he was gone. I heard his footsteps as he moved down the hall.

I smiled. He was trying to walk quietly on tiptoe in his heavy work boots with his huge feet. He wasn’t having much luck with it. He still sounded like King Kong.

It was now after eleven o’clock in the evening. With shaking fingers I smoked a cigarette, something I had not done since college. I still had the jitters. According to LaDonna, the “point of separation,” the phrase coined to describe the transitional period when women leave their abusers, is the most dangerous time of your life. I had tensed up my muscles so much that they hurt. My shoulders felt as if they were resting at the bottom of my ears. I exhaled and blew the smoke into a cloud in front of my face.

Through the window, I watched the lights in the apartment building across the street go out one by one. I tried to imagine the lives behind the drawn shades and closed curtains.

The late-night TV shows were about to come on. Work clothes for the next day were laid out; showers had been taken. People with normal lives checked the locks on the front door before they went to bed. They had walked the dog. They fluffed the pillows and set the alarm clock. People with normal lives clicked off the lamp on the nightstand. People with normal lives.

Normal lives.

What was a normal life?

I was a woman with a college degree, my name on a mortgage, one car note, a Sears bill, and a “good job.” Wasn’t that “normal”? And here I sat with three cigarette burns, bruised ribs, scratched knuckles, and a swollen eye.

“Sleep well, Opal. You’re safe now.” LaDonna’s words echoed in my head.

For years I slept curled up in a ball on the edge of the bed with one eye open. How in the world had I ever thought that I had a normal life?

I would try to have one now.

That night I stretched out in the little bed and buried my face into the pillow. And slept. Well.

I sit in the shade of my own tree now, but it wasn’t too long ago, I didn’t have a twig, much less a tree to sit under. I was running from a marriage that was no good. It took me fifteen years to take that first step, but once I did, I just kept going. Now, several years have come and gone. Already! Time flies when you’re having fun. Or running for your life.

I married my college boyfriend, Ted, when I was twenty-one.

After a few years of marriage, I knew that I had made a terrible mistake.

But once I was in, I didn’t know how to get out. It was like being in prison. And I had a life sentence with no chance of parole.

I got three squares a day and had a bed, but that was it. There was hard labor and solitary confinement if I was uncooperative. Or if, as in Ted’s words, I acted like a “sassy, smart-mouth bitch.”

Even when it got as hot as hell in the summer, I wore long sleeves. My arms were always bruised. One August, I wore turtleneck sweaters to work for two weeks until the marks of Ted’s handprints faded where he had tried to choke me.

I know what you’re thinking: She sounds so articulate! She could get a job anywhere. Why didn’t she just leave? Why did she stay and put up with that?

How many times have I asked myself those questions? How many times did I beat myself up after Ted beat me up? I’ll turn the tables on you. You don’t understand what I was dealing with. And for years, I didn’t understand, either. By the time I did, it was almost too late.

The slaps, pushes, kicks, and punches didn’t start right away of course. The insults, put-downs, scoldings, and verbal abuse began slowly. He started with “constructive criticism.” I knew that I was in for it when he said, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but . . .” or, “This is for your own good.” By the time he finished with me, I felt like I was six inches tall and three years old, standing in the corner for bad behavior.

Ted was charming in college. Smart and handsome, athletic and talented, he played a saxophone that Sonny Rollins would have been jealous of. Everyone loved Ted. Especially women. The cutest girls on campus threw themselves at him. I, on the other hand, was awkward and strange. I liked Bach, the Indian-influenced music of Alice Coltrane, Herbert Marcuse, and Jane Eyre. Ted could dance. I had two right feet and that is worse than two left ones. Ted talked and dressed “cool.” I didn’t.

So when Ted Hearn asked the tall, gangly, studious-looking redbone girl from Ohio with straw-colored hair, braces, and glasses with lenses thicker than bullet-proof glass for a date, everyone was shocked. Especially me. I had never had a boyfriend like Ted before. I was thrilled and proud to be seen with him. I was finally “cool.” Ted took care of everything. He was wonderful. He made sure that my friends didn’t take advantage of my weakness for loaning out books and albums and helping with term papers. He helped me deal with my mother, who had a tendency to be a little overbearing and critical. Ted helped me with my class schedules; he even started to suggest the subjects for the paintings that I did, because I thought that I was a painter. He was so protective of me. At least, that’s what I thought at the time.

By the time we got married, the trap was nearly set. I was already isolated from my friends, who had been cut out of my life by Ted, who wanted only to be with me. He had alienated me from my mother, and my poor easygoing father accepted without question what he interpreted as a natural transition of authority: from father to husband.

Two weeks after our honeymoon, Ted and I moved to Atlanta, where he had taken a job. I was now three states and fourteen hours away from home. I had a new house, a car of my own (that was in Ted’s name), and a part-time job. I was pregnant and I didn’t know anybody in the big, long state of Georgia, not one soul. By the time our daughter, Imani, was born, the cheese was in the trap.

It started with an argument, I think. I don’t remember now what the argument was about. It ended with Ted backhanding me and then apologizing. It happened so fast. And then we made love. And it didn’t happen again for six months. I remember saying to myself, Maybe I imagined that. Maybe it didn’t really happen.

But, of course, it happened again. A push and a shove into the stove. Dinner was late that night. It was early the next night and I was slapped because it was cold. This was before microwaves.

I thought about calling for help. But who was I going to call? Imani? My friends? I didn’t have any friends. The only people I knew were the people Ted knew. And he was very careful to make sure that I didn’t get too friendly with anyone. I couldn’t call my parents, either. In my family, whining is not allowed. Thanks to Ted, Mother and I were barely speaking. And Dad’s gentle nature hid a strong resolve when it came to working out your own issues in a marriage. “If you make your bed too hard,” he always said, “be ready to turn over more often.” I turned over and over and over.

So I did nothing. The years of my life flew by.

Unlike prison, there was never time off for good behavior, because Ted beat me whether I was “good” or not. What was “good”? He made me feel small.

As the years passed, I became numb. I did not feel at all. The only thing that made me smile was Imani, our daughter. And yet there were days when, even with her, I couldn’t remember how. My voice grew softer and quieter and then went silent. I nearly disappeared altogether. Except when I screamed. I had volume control. There was loud. And there was louder. When Ted told me to shut up, I bit through my bottom lip and sent the screams deep inside.

I saw a silly movie once about voodoo and zombies. I watched the campy-looking zombie stagger through the scenes with its black-circled eyes and a blank expression. I could have performed that role myself without makeup, script, or rehearsal. Ted had beaten the humanity out of me.

I did ask for help a few times when I could get up the courage and get past the humiliation.

I just didn’t take the advice that I got.

I called a domestic violence hot line. The woman told me to pack up my daughter and leave Ted. Right then. Take only my purse and my keys. They had a shelter on Peachtree. Leave Ted and do what? I was only working part-time then. Imani was six. What would I do for money? Where would I live? How would I live?

Another time, after we moved north, a hospital social worker visited me, uninvited. I had been kept overnight for observation after Ted kicked me in the abdomen and broke a couple of my ribs. She touched one of the dark red roses that Ted had sent me from an expensive florist. I know that she saw the card that read: “I don’t know what got into me. I love you so much. I would die if you left me. Ted”

The woman sat down in the chair next to my bed and looked me straight in the eye. She didn’t say good morning; she didn’t say, “How are you feeling?” She just looked at me without smiling.

“If you don’t leave him, you will die.”

And then, there was the memorable occasion that I talked with Miss Thelma, one of the elders at my church. She clucked her tongue at me.

“Honey, there ain’t no problem with that man. Now he’s got a good job at the auto plant and he brings home good money. You-all have that nice house over there on the east side and you got your own car. You ain’t got nothin’ to complain about. What’s the matter with you?”

Well, that was no advice at all.

I was afraid to leave Ted. And I was afraid to stay.

I left him four times. And I came back four times. I called the police so often that they knew me by my first name: “Opal, are you going to let us lock him up?”

And I did a few times.

Ted called me from jail: “Are you gonna come and get me out? I’ll kick your ass if you don’t.” Ted wasn’t charming anymore.

I pretty much lost everything.

The few friends I’d made stopped calling because I always canceled lunch and girls’ night out at the last minute. And I wouldn’t return their telephone calls. I didn’t want to hear what they were telling me.

I missed the sermons and the music at church that gave me so much comfort. I stopped going to church because I dropped out of the choir. And I dropped out of the choir because I missed too many rehearsals. I missed too many rehearsals because I was ashamed. I didn’t want God to see my black eyes, bruises, and swollen lips. I didn’t want him to know.

Except for work and the grocery store, I became a recluse. I hardly saw anyone. I learned, well, sort of, what set Ted off. I could walk on eggshells in high heels. I was good. I could sense an electricity in the air; I could tell from the set of his jaw or the look in his eye. Sometimes I could tell whether I was going to be slapped or kicked. Or both. I should have used that ESP on better things.

It’s true that you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. I call it the ruby slippers syndrome: you can wear those shoes all over the place, but until you click your heels together and chant the magic words, nothing will happen.

I eventually made up with my mother and my parents offered me sanctuary. They knew what was going on. But I wouldn’t take it.

My brother, JT, threatened to just show up one day with a U-Haul to take me, Imani, and all of our furniture and other belongings away. I refused to go.

Even my cats left. There was a time, some years ago, when Ted would come home after he’d been drinking and pick up one of them and throw him against the wall to see if cats would bounce.

They don’t.

You don’t have to tell cats anything twice.

By the time Imani was ten, she knew that her mommy and daddy weren’t like other mommies and daddies or like the ones that she saw on TV. The households of her friends may have been noisy and hectic, but the muffled sounds of shrieks, screams, and banging furniture were absent. The mothers of her girlfriends didn’t have bruises or black eyes. My daughter is a smart kid. She never brought her friends home with her.

And I was stupid and blind enough to believe that because Imani was a child, she didn’t notice what was happening in her home.

“Mommy, did Daddy hurt you?”

Imani asked this question again and again over the years until it became more of a statement than an inquiry.

“No,” I lied. “Daddy was just a little upset.” My eyes were puffy because Daddy was “a little upset.” The kitchen chair was a pile of sticks because Daddy was “a little upset.”

Who was I kidding?

Certainly not my daughter. I became a “shadow” mommy, there but not there, lurking around the edges of my daughter’s life.

Imani left for college when she was eighteen, and she hasn’t really been home since. She spent the holidays with my parents. Ted got worse after she left. Once she was gone, there was no more need for me to bite my lip to keep from screaming. There was no one to hear.

And still, I stayed.

I must have been waiting for a sign from God. It fi- nally came.

Ted and I went to Kmart. I think we were looking for a lawn mower or some yard tools or something, I don’t really remember now what it was. We didn’t find the lawn mower, but we picked up a few other things, moved at a snail’s pace through the checkout line, then headed home.

Ted was quiet in the car.

I knew then.

The automatic garage door hadn’t finished its descent before he started in on me.

“Think you’re pretty slick, don’t you?”

My stomach began to churn.

“Ted, what are you talking about?”

His voice got louder and he clenched and unclenched his fists.

“I saw you looking at that man in the white shirt. I saw him looking at you! Who is he?”

The first punch caught me on the back of my head. The second one grazed my right eye. I saw stars and dropped to the floor.

“What man?”

“Bitch! I am tired of this shit! Do you think that you can sneak around on me!”

He kicked me in the ribs and in the stomach. My head was ringing and I remember thinking that now I knew how a football felt. A stupid thought, really, when you’re being beaten. But my mind was desperately trying to separate itself from the pain and the fear. I tried to open my eyes and look at Ted as I defended myself. But my left eye was bleary from the tears. And my right eye was swollen shut.

“I don’t know who—”

“You’re my goddamn wife and don’t you forget it!” he bellowed as he dragged me up from the floor by the collar of my shirt. “I’ll take care of this shit right now!”

He threw me against the wall and stormed off into the family room. I thought for a moment that he was going to get a gun and shoot me, but Ted doesn’t have a gun. His fists and feet have always been lethal-enough weapons. I just pressed against the wall where he had thrown me, stuck there like a piece of gum. My legs were so wobbly that I could barely stand up. And my vision was so blurred that I couldn’t see to run.

But I saw him approaching, his form dark and ominous. In his hand was a lighted cigarette.

“I’ll take care of this right now,” he repeated. “Your lover boy will know that you’re my wife. And you, you stupid bitch, you’ll know, too.”

He burned me in three places with that cigarette.

Ted left me in a heap on the floor of the foyer whimpering and moaning, my right eye cut and bleeding, my ribs sore, my kidneys bruised, and my arm and neck burned from the small glowing tip of a cigarette.

He went out to meet some friends for drinks at a sports bar.

I didn’t leave him that night.

I didn’t even leave him the next night.

To this day, I don’t remember a white-shirted man in Kmart who gave a hippy, tired-looking middle-aged woman the eye.

I slept in the same bed with Ted for two more nights.

On the third night, the straw broke the camel’s back.

I was brushing my teeth.

It was late and Ted wasn’t home yet. I was tired and had to work the next day, but I knew that I would probably be up all night because he would come home drunk and we would fight about God knows what. I turned off the faucet and caught a glimpse of the woman in the mirror.

I didn’t know who she was.

I hadn’t studied myself in the mirror for years. I usually did just enough to get my hair combed and put my glasses on straight.

My hair was white at the temples and there were pouches under my eyes. My right eye was a mess, completely black-and-blue and still huge. My nose was crooked (it had been broken twice) and there were deep gorges in my cheeks like the Grand Canyon. My complexion was gray. There was a welt on my neck that was several weeks old, but it wasn’t healing right. I’d have an ugly scar there no matter what I did.

And there were small circular sores on my arm and neck where Ted had burned me with the cigarette. I had been putting salve on them, but they still looked raw and nasty.

I looked like an old crack head.

I stared at that woman for a long time. And she stared back with sad, tired eyes.

My mind was confused. The Opal that it remembered was a caramel-colored woman with hair the same color and brown eyes. It remembered a woman with dimples in her cheeks when she smiled and a pointed nose and a little more meat on her bones. Where was the woman who liked fusion jazz, Latin American literature, and Egyptian mythology? The one who dreamed of studying art in Paris and living in a loft? What happened to the Opal who wanted to wear a beret on top of her Afro and find out what was so great about Whistler’s Mother?

“What is this shit?” Ted would ask, looking over my shoulder when I was painting. When he was sober and mean (as opposed to being drunk and mean) he said nothing at all. I’m not sure which was worse.

When Ted began to take out his frustrations on my canvasses, I only painted when he wasn’t home, hiding the pieces in the basement behind the furnace. I pulled them out once a week, then once a month, and then I stopped pulling them out at all. As I looked into the eyes of the defeated-looking woman in the mirror, I realized that I hadn’t looked at those canvasses in over ten years.

Hey! Didn’t you used to be Opal Sullivan? Didn’t you used to be her?

I didn’t know the woman in the mirror and I wasn’t sure that I wanted to. She was the scariest thing I’d seen in years. And she was me.

Then I noticed the ugly red burn on my upper arm.

Over the past fifteen or so years, I had been punched, slapped, backhanded, beaten with a belt, and kicked. I had been belittled and ridiculed. I had been “restrained” (a polite word to use when you have been locked in a closet) and almost choked. I had been smacked and pinched.

But I had never been branded.

And that’s just what Ted had done. He had branded me just like they used to brand slaves.

What was next? Would he stick pins in my feet? Tie me down and put wet bamboo sticks under my fingernails? Would he kill me?

The woman inside me had an answer to that question. The social worker’s words came back: “If you don’t leave him, you will die.”

Ted had his own litany: “If you try to leave me, bitch, I’ll fucking kill you.”

Well, maybe he would and maybe he wouldn’t. I might end up dead.

But I’d be free.

The woman in the mirror was so angry that her face almost split open.

I would be a lot of things in this life, but I would be damned in hell if I’d be branded like a steer.

I left with the clothes on my back and my purse.

I wasn’t sure what to do next.

My parents lived in Florida, and Pam, the only friend I had left that Ted hadn’t run off, was out of town. I was too embarrassed to call anyone else or go to a neighbor’s. With shaking fingers I leafed through the phone book until I found the number that I was looking for.

“Women’s Crisis Center, LaDonna speaking.”

“I, uh . . . I need a place to stay. Just for a few days.”

LaDonna’s voice was calm. “What’s your name, dear?”

“O-Opal Hearn.”

“Are you in a public place, Opal?” she asked.

I told her that I was.

“Is he around?”

“No, no, he’s gone. I’m in my car. At a gas station.”

“Good. You have transportation. All right, here’s what I want you to do. . . .”

The directions were crystal clear. I parked in the small lot behind the innocuous-looking apartment building. A woman holding a flashlight stood in the middle of the lot. She waved me over like she was directing an airplane on landing.

“I’m LaDonna,” she said, smiling. “Come on; let’s get you settled.”

She was petite and wore her waist-length bleached blond hair teased up in a style that I hadn’t even seen on a country and western singer in twenty years. At least two layers of makeup covered her fifty-plus-year-old face. She was dressed in blue jeans, cowboy boots, and a fringed Western-style shirt. Her earrings were almost as big as she was. She looked like Dale Evans on acid. But LaDonna wasn’t singing “Happy Trails.” There was a no-nonsense tone in her voice. This was a woman who was used to giving orders and having them obeyed. A small frown darkened her features. She touched my chin gently and turned my face to the side.

“Has anyone looked at your eye?”

I could barely talk. I shook my head.

She smiled sympathetically and passed me a handful of tissues.

“We’ll take care of it,” she said confidently. She took me by the arm and led me toward a taupe-colored door that was discreetly set in the recessed entryway. “You don’t want to go blind in that eye.”

“Opal R. . . . what’s the R stand for?” LaDonna asked as she filled out a form.

“Renee,” I told her, still blowing my nose.

“Nice name,” she commented. “Just sign here.”

I scribbled something that looked like my signature.

“I’m going to recommend that you not go to work tomorrow. You need a thorough medical exam. I’ll ask Christine, that’s the nurse-practitioner, to look at your eye tonight. But you should see a doctor just to make sure it’s nothing serious,” LaDonna said. “I’ll call your supervisor in the morning and—”

“No!” I shouted, suddenly getting my voice back. “No! Please . . . I’ll . . . I’ll just call in . . . sick or take a vacation day or something.” A lump was forming in my throat. I started crying again. “I—I don’t want them to know. . . .”

LaDonna’s expression was warm, but her words were as sharp as razor blades: “Opal, they know already.”

The humiliation and embarrassment swept over me like a tidal wave.

Of course they knew. I have had black eyes and bruises that paint and plaster couldn’t cover up. I wanted to crawl under LaDonna’s desk and hide.

She smiled and patted me on the arm. “It’s a form of denial, Opal; we’ve all been through it. It’s the work-ethic shit. We are raised from the cradle to get over it. Suck it up! Ignore it,” she said matter-of-factly. “The son of a bitch that I was married to was six feet, five inches tall and weighed over three hundred pounds. I’m barely five feet tall and weigh one hundred pounds. He threw me against a wall once and cracked my pelvis. I went to work the next day with a cane telling everyone that I was hav- ing trouble with my arthritis! Who was I kidding? Only myself.”

My ribs hurt when I laughed. So I cried instead.

Christine’s fingers were cool and firm. Her blue eyes were nearly unblinking as she listened to my heart and probed my abdomen and back.

“Does this hurt? This?”

I shook my head.

“Let me have a look at that eye again.” She turned her head slightly to the left as she studied me. “Good. I don’t think anything is broken. Bruised ribs, that’s all. I want a specialist to check out your eye, though.” She wrote something on a notepad, tore off the top sheet, and handed it to me. “Here’s the name of an ophthalmologist. She’ll see you without an appointment; just tell her receptionist that you’re a client of the Center.”

“OK,” I said. “Thank you.”

“No problem,” the nurse replied. “Just be sure that you go see the doctor. You can’t take black eyes for granted. I should know. The last one I got nearly blinded me. I’ll never be able to see more than shadows out of my right eye.”

I must have gasped, because the nurse smiled at me and folded her arms across her chest.

“I know. I don’t look like ‘the type.’ ” Christine sighed dramatically, then flashed me an impish grin. “I get that a lot. But there are all types, Opal, and that’s what you have to understand. This can happen to anyone. Unfortunately, our society has insulated itself with an antiquated image of a battering husband. They don’t all wear T-shirts and dirty blue jeans and guzzle beer all day. They are mayors, ministers, corporate types, and teachers. They are policemen, believe it or not. They are your coworkers and your funeral director. They are everywhere.” She bandaged my forehead.

“My boyfriend was a medical student. He came from a ‘nice home,’ whatever that is. And went to ‘nice schools’ and lived in an ‘upscale neighborhood.’ ” She paused for a moment and looked at me.

I noticed then that one of her eyes didn’t move in sync with the other one.

“He was so ‘nice’ that he tortured cats and squirrels when he was a kid. I found out later that he had punched his prom date and broke her jaw when he was seventeen. When he grew up, he graduated from small animals and prom dates to girlfriends.” She smirked. “And I wanted to be a doctor’s wife. Can you imagine?” Then she gave me an engaging grin. “After I spent two weeks in the hospital after he tried to kill me because I was leaving him, I decided that I would rather be a doctor myself. I’m going to medical school in the fall.”

LaDonna settled me into a small room with three beds.

“We’re under capacity tonight, so you’ll be on your own. The room across the hall and the room next to yours are occupied, but I don’t think you’ll be disturbed. Oh, and just ignore any clanging you hear from the basement. We had a broken pipe scare and the maintenance man is finishing up down there.”

She set an extra pillow on the bed and patted me on the shoulder.

“Sleep well, Opal. You’re safe now.”

...

I sat in the corner of the TV room by myself.

The woman in the room next to mine walked in on bare feet and got a Coke out of the vending machine. She nodded at me and padded out. I heard the maintenance man coming up the basement steps with the gait of King Kong. The basement door creaked when it closed and he clomped down the hall and stepped into the TV room, setting his toolbox on the floor. He, too, went to the vending machine to get a can of soda.

“Oh! Excuse me; I didn’t know that anyone was in here,” he said apologetically when he noticed me.

I turned my face away from his and scooted the chair quickly into a shadow. I wasn’t ready to face anyone else with a fat lip and one eye that was swollen and multi- colored.

“It’s OK,” I told him. “I was just sitting here.”

He paused for a moment. “Do you want me to turn on more lights for you?”

I shook my head. “No, thank you.”

“Then I’ll let you get back to it,” he said, giving me a nod and a quick smile. He had a nice face. And then he was gone. I heard his footsteps as he moved down the hall.

I smiled. He was trying to walk quietly on tiptoe in his heavy work boots with his huge feet. He wasn’t having much luck with it. He still sounded like King Kong.

It was now after eleven o’clock in the evening. With shaking fingers I smoked a cigarette, something I had not done since college. I still had the jitters. According to LaDonna, the “point of separation,” the phrase coined to describe the transitional period when women leave their abusers, is the most dangerous time of your life. I had tensed up my muscles so much that they hurt. My shoulders felt as if they were resting at the bottom of my ears. I exhaled and blew the smoke into a cloud in front of my face.

Through the window, I watched the lights in the apartment building across the street go out one by one. I tried to imagine the lives behind the drawn shades and closed curtains.

The late-night TV shows were about to come on. Work clothes for the next day were laid out; showers had been taken. People with normal lives checked the locks on the front door before they went to bed. They had walked the dog. They fluffed the pillows and set the alarm clock. People with normal lives clicked off the lamp on the nightstand. People with normal lives.

Normal lives.

What was a normal life?

I was a woman with a college degree, my name on a mortgage, one car note, a Sears bill, and a “good job.” Wasn’t that “normal”? And here I sat with three cigarette burns, bruised ribs, scratched knuckles, and a swollen eye.

“Sleep well, Opal. You’re safe now.” LaDonna’s words echoed in my head.

For years I slept curled up in a ball on the edge of the bed with one eye open. How in the world had I ever thought that I had a normal life?

I would try to have one now.

That night I stretched out in the little bed and buried my face into the pillow. And slept. Well.

Notă biografică

Sheila Williams