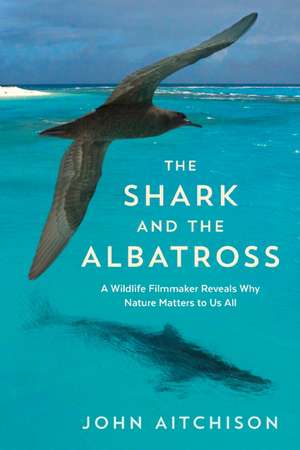

The Shark and the Albatross: A Wildlife Filmmaker Reveals Why Nature Matters to Us All

Autor John Aitchison Cuvânt înainte de Carl Safinaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 mai 2016

For twenty years John Aitchison has been traveling the world to film wildlife for a variety of international TV shows, taking him to far-away places on every continent. The Shark and the Albatross is the story of these journeys of discovery, of his encounters with animals and occasional enterprising individuals in remote and sometimes dangerous places. His destinations include the far north and the far south, from Svalbard, Alaska, the remote Atlantic island of South Georgia, and the Antarctic, to the wild places of India, China, and the United States. In all he finds and describes key moments in the lives of animals, among them polar bears and penguins, seals and whales, sharks and birds, and wolves and lynxes.

John Aitchison reveals what happens behind the scenes and beyond the camera. He explains the practicalities and challenges of the filming process, and the problems of survival in perilous places. He records touching moments and dramatic incidents, some ending in success, others desperately sad. There are times when a hunted animal triumphs against the odds, and others when, in spite of preparation for every outcome, disaster strikes. And, as the author shows in several incidents that combine nail-biting tension with hair-raising hilarity, disaster can strike for film-makers too.

John Aitchison reveals what happens behind the scenes and beyond the camera. He explains the practicalities and challenges of the filming process, and the problems of survival in perilous places. He records touching moments and dramatic incidents, some ending in success, others desperately sad. There are times when a hunted animal triumphs against the odds, and others when, in spite of preparation for every outcome, disaster strikes. And, as the author shows in several incidents that combine nail-biting tension with hair-raising hilarity, disaster can strike for film-makers too.

Preț: 157.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 236

Preț estimativ în valută:

30.14€ • 31.66$ • 25.33£

30.14€ • 31.66$ • 25.33£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781771642187

ISBN-10: 1771642181

Pagini: 246

Ilustrații: 28 color photos, Maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Greystone Books

Locul publicării:Canada

ISBN-10: 1771642181

Pagini: 246

Ilustrații: 28 color photos, Maps

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Greystone Books

Locul publicării:Canada

Recenzii

"Aitchison's great hope is that the rest of us, looking at his images, reading his tales, will love these animals as he does. That we will be moved. I was. You will be."

—Virginia Morell, Author of Animal Wise: How We Know Animals Think and Feel

"Through words and photos, Aitchison transports readers to far-flung corners of the earth and displays, vividly, why we should care about our natural world."

—Paul Nicklen

"This is a lovely book, vividly written, giving us a fascinating insight into the world of wild life photography. It is a must for all those who enjoy insights into the natural world."

— Alexander McCall Smith

—Virginia Morell, Author of Animal Wise: How We Know Animals Think and Feel

"Through words and photos, Aitchison transports readers to far-flung corners of the earth and displays, vividly, why we should care about our natural world."

—Paul Nicklen

"This is a lovely book, vividly written, giving us a fascinating insight into the world of wild life photography. It is a must for all those who enjoy insights into the natural world."

— Alexander McCall Smith

Notă biografică

John Aitchison is an Emmy and BAFTA Award–winning wildlife filmmaker. He has worked with National Geographic, PBS, the Discovery Channel and the BBC on series including Frozen Planet, Life, Big Cat Diary, Springwatch and Yellowstone. He lives in Scotland.

Carl Safina is the author of seven books, founding president of the not-for-profit Safina Center, and a winner of the Orion Award and a MacArthur Prize, among others. His most recent book is Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel.

Carl Safina is the author of seven books, founding president of the not-for-profit Safina Center, and a winner of the Orion Award and a MacArthur Prize, among others. His most recent book is Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel.

Extras

Foreword by Carl Safina

I’m a big-picture guy, and John Aitchison has given us a big-picture book. The shark, the albatross, falcons streaking high overhead, penguins flying down into the icy blue. And more.

Many people behind the camera, frankly, aren’t the best with words; their art is in the seeing and their lens does the talking. And that is usually how it should be. We all talk too much and we can often learn more by quieting down and just watching. Through their lenses, we have acquired our impressions of much of the world. It’s hard to overstate the importance of that.

But Aitchison is unusual because in addition to being a fine cinematographer, he is good with words. He writes gracefully, insightfully, modestly. He is straightforward. He is evocative. Years of seeing detail through the lens has imbued him with the rare skill of painting with words.

Words, especially written words, are completely illusory. To wield them well one has to be a bit of a magician. Yet Aitchison pieces written words together in a way that makes us see and feel. That is the best thing a mere writer can do.

In these pages Aitchison is aware that he is a visitor, and privileged to be where he is, observing what he is seeing. Cinematographers and writers often have opportunities to see what few people can see. Even the best wildlife researchers, tied as they are to their own special species and specific field sites, seldom glimpse as much firsthand as has John Aitchison. His job is to help us see it with him, and he takes the task seriously and he delivers, solidly.

What I most like about Aitchison’s approach is that, implicitly, he views the living world as sacred. He ventures out as though he is stepping into a cathedral of planetary proportions—which indeed he is. “I can think of little worse than coming here to film bears and having to shoot one instead,” he writes, “but it is a possibility we have to face because they are formidable animals.” Two things here: he forebears (no pun intended) twice in the same sentence. Usually, guns change the balance of power between humans and the Living World, but not in Aitchison’s mind; he hates the idea. Second, he calls the bears “formidable,” which in itself is restrained. A polar bear is in fact very dangerous to an unarmed human. The only thing more dangerous—is an armed human.

This book has few pretentions. We are merely treated to a view of the world at a special point in history. Ours is the time when we remain on Earth in the company of the great creatures: wolves, whales, falcons—. We can still look overhead to see scarves of geese flowing along ancient annual migration routes in the skies. Great fishes still swim beneath the sea, and penguins—perhaps the strangest birds in all the world—continue to weave themselves through the sea surface and plunge into swarms of krill.

We have changed the world greatly, and in diminishing the living world we have diminished ourselves. “It is impossible to travel widely,” Aitchison ventures, “without seeing that many wild animals are struggling.”

Yet these are not pages of doom. They reflect the energies with which all life around us strives to stay alive—and beautifully so.

From Chapter 2: Hunting with Wolves

Yellowstone is the only place in the United States where bison have lived continuously since prehistoric times, but by 1903 there were just twenty-three of them left in the park and they were not breeding successfully. The continent’s once vast herds had already been shot to oblivion. A few captive survivors were brought to join the small wild herd here and they made a crucial difference. Since then Yellowstone’s bison have slowly recovered.

The wolves had an even harder time. There were once more than a million grey wolves in North America and they killed animals from the settlers’ herds as readily as they hunted elk or bison. Killing wolves to protect cattle was seen as a matter of pride and necessity for ranchers and the Government. Even living in a National Park was no protection. When the Secretary of the Interior protected most of the park’s animals from hunting, in 1883, the regulations did not apply to wolves and everyone shot them, including the Army. The last two wolves in Yellowstone were killed in 1926 and, with their main predators gone, the park’s elk boomed. They overgrazed the plants, suppressing other herbivores, such as beavers. To redress the balance and amid great controversy, in 1995 and 1996 a Government agency brought thirty-one wolves here from Canada and released them in the Lamar Valley, close to Druid Peak.

Our journey takes us past this mountain, which gave its name to the first pack of wolves to live in its shadow in seventy years. The Druid Peak wolves thrived here, among the naïve herds of elk. In time the elk numbers started to fall, of course, but there are still plenty here and this morning we can see their tracks in the snow, as though they have been writing their stories on a page: stories about their search for food and shelter during the night, about their urge to seek safety with others and sometimes even the story of their death. All the valley’s recent history is laid out for anyone to read, until the next snowfall wipes it clean. Most of the female elk and their calves are high on the hillside, digging with their front feet to expose sparse dry grasses. Perhaps they feel safer up there, where the snow is not too deep to run away. Even so they are barely scratching a living, becoming weaker every day and a little easier to catch. By the end of the winter some of them will have consumed the marrow in their own bones.

A raven passes overhead, flying high and direct. We follow its line across the river and it leads us to the wolves. The whole Druid pack is gathered in a clearing on the forest edge. We watch them intently, studying how each wolf fits into its extended family. Some are curled up asleep. One stands off to the side, leaping again and again, trying to bite a dangling pinecone from a tree. When it succeeds it immediately drops the cone and starts to chase its own tail. A dark wolf, clearly subordinate, greets the palest one, wagging his tail and squirming as low as he can, to lick her muzzle. This is how the hierarchy works, each pack member is in its own place below the pale wolf and her mate: the alpha pair. It’s fascinating to see this played out, but there are sixteen wolves to keep track of and there’s half a mile between us. To the naked eye they are not much more than dots and, in order to film them closer, we will need to find and follow them every day. In just a few hours wolves can travel enormous distances and for two thirds of our time here it is going to be dark.

*

Every year since the wolves were reintroduced, scientists have fitted some of them with collars which produce radio signals. Rick McIntyre is a Biological Technician for the Yellowstone Wolf Project. His job is to monitor the radio-collars in this part of the park and record as much as he can about the behaviour of the Druid Peak wolves, and several other packs too. We find him by the roadside, surrounded by a large group of people with telescopes on tripods. Rick is staring through his own telescope and patiently describing exactly where the wolves are, using rocks and trees as landmarks, so the visitors can find them too. He raises an aerial, turns it this way and that, while listening for the collars’ beeps, then changes the orientation and listens again. He speaks into a pocket recorder:

“569 is there right now and so is 480. 302 is out of sight somewhere to the right.”

On their way here, other people have seen different wolves. Like Rick’s, their descriptions are a mixture of numbers and nicknames. Nathan and I meet Laurie, a visitor who has spent years watching Yellowstone’s wolves. She explains to us how to tell the sixteen Druid wolves apart. Eight of them are black and eight are “grey” (actually a sandy and dark mixture, quite like a pale German Shepherd dog). Four are collared and known by numbers: 569F is the beautiful alpha female, so pale she is almost white, her mate, 480M, is the black alpha male and his brother is 302M. The other collared wolf is a younger male. Laurie says male wolves are collared more often than females because, instead of making straight for the trees, they stop to look back at the helicopter which is carrying a biologist with a dart gun. Once they are collared the scientists move the unconscious wolves to the centre of their territory and revive them together. It’s safer than waking up alone, feeling groggy, with another potentially hostile pack nearby.

Laurie carries on listing the Druids. It’s a dizzying mass of information: There are six yearlings, some with marks on their fronts and sides, like the grey bars which separate the black wolves, “Light-bar” and “Dull-bar.” Most of these yearlings are the alpha pair’s pups from two summers ago, which the whole pack helped to raise. They are all female. There are seven younger wolves too, the most recent pups, now fully-grown. None of them have names and they are hard to tell apart. Laurie recognises this group by the ruffs on their necks, which look like raised hackles, and because they behave like pups too: it was probably one of these we saw jumping for the pinecone. Identifying the wolves is the vital first stage in predicting what they might do. It could make all the difference between being in the right place or the wrong one when it comes to filming. There’s a lot to learn and we have a month in which to do it.

The visitors have come from a wide range of countries. Many have seen and been captivated by these wolves on television or on the Internet: the Druids are the most famous wolf pack in the world and the most watched. 302 is everyone’s favourite. He was sometimes called Casanova when he was young, for the daring liaisons he had with females from other packs, under the noses of their own males. He even has his own blog, run by someone in Florida. Since the demise of the Plains Indian tribes, a century or more ago, people have rarely connected so strongly with wild wolves. Such empathy is only possible because Rick, Laurie and many others, have spent an immense amount of time coming to knowing individual wolves and their stories. Rick alone has clocked up more than four thousand days. For the last four and a half years he has been here seven days a week but, when Laurie introduces us, he hides his dedication with a joke: “I once caught a cold in 1997 but I came in anyway.”

He welcomes us and explains that the pack usually moves every few days, but this year the heavy snow has kept them in the Lamar Valley for an unprecedented six weeks. Although they have often been visible from the road so far, they could decide to leave at any time.

*

There was a fight last night in one of Cooke City’s bars. Afterwards we could hear some boys from Idaho playing chicken with their huge snowmobiles on the icy main street. We’d had an early night, not to avoid the fighting, but because we had to be up at 4:30 and ready to drive into the park before first light.

Inter canem et lupum (between the dog and the wolf) meant twilight in the Roman world, when wolves were common everywhere. A dog barks as we leave town. Cooke City’s dogs must be early risers, because there is not a hint of light in the sky as we drive towards the park entrance. Dark mountains crowd close to the road: Abiathar Peak, Mount Norris and the Thunderer. There is nowhere in Yellowstone lower than the top of Britain’s highest summit and these mountains are more than twice that high. Through gaps in the trees we glimpse snow-covered prairies, where streams trickle between hummocks as smooth and white as iced cakes. How should we search for a single pack of wolves in so much space? As we near the Lamar Valley the light comes up and we stop to search for wolf-shapes moving on the snow, studying the elk closely, looking where they are looking. The elk seem relaxed and nothing moves, so we drive on and try again. In each place we listen and finally we hear the Druids howl.

America’s early settlers described wolf howls as mournful or blood-curdling, a projection of their own fears onto the sounds which wolves make to keep their packs together and their neighbours away. For a wolf pack to thrive they need the exclusive use of a large territory with plenty of prey. Advertising their numbers by howling together is a show of strength. To us, without any livestock to lose, the sound is beautiful, like a choir singing in close-harmony. Each wolf joins in with the others at a different pitch, to give the impression of a stronger pack: one to leave alone. Their voices carry astonishingly far, echoing from the face of the Thunderer and sustained by the distance, long after they have lowered their muzzles. It is wild music I do not want to end.

*

We find Rick at a place called Round Prairie, checking the signals from the radio collars. He says there are wolves close by, somewhere in the trees, so we set up the camera and wait, hoping they will show themselves. There are seven bull elk in the meadow: enormous deer, weighing perhaps half a tonne each, with pointed antlers, spanning more than a metre on either side. They seem very wary, eyeing the shadows. Perhaps the wolves are just checking them, staying out of sight rather than facing one down, as Rick says they sometimes do, to test its resolve, daring it to make the first move.

The signals fade. The wolves are moving away down the valley, hidden by the trees. We follow along the road until they appear on the far side of the river, trotting in a line: first the alpha pair then 302 and a few of the others. While the adults have been away another wolf has used their absence to introduce himself to the younger pack members. He’s a lone grey male. The yearling females are particularly pleased to see him and there is a great deal of sniffing and tail wagging. The lone male knows he is taking a risk and when he’s spotted by the returning brothers, 480 and 302, he immediately break into a run. They give chase but the alpha male soon stops. 302 runs on. He has more to lose because he’ll be able to mate with the young females in his pack, as long as he sees off the competition. The interloper runs in a loop, knowing his pursuer will follow his trail by scent rather than cutting the corner, which allows him to check whether he is still being followed. He is and 302 chases him into the distance.

I’m a big-picture guy, and John Aitchison has given us a big-picture book. The shark, the albatross, falcons streaking high overhead, penguins flying down into the icy blue. And more.

Many people behind the camera, frankly, aren’t the best with words; their art is in the seeing and their lens does the talking. And that is usually how it should be. We all talk too much and we can often learn more by quieting down and just watching. Through their lenses, we have acquired our impressions of much of the world. It’s hard to overstate the importance of that.

But Aitchison is unusual because in addition to being a fine cinematographer, he is good with words. He writes gracefully, insightfully, modestly. He is straightforward. He is evocative. Years of seeing detail through the lens has imbued him with the rare skill of painting with words.

Words, especially written words, are completely illusory. To wield them well one has to be a bit of a magician. Yet Aitchison pieces written words together in a way that makes us see and feel. That is the best thing a mere writer can do.

In these pages Aitchison is aware that he is a visitor, and privileged to be where he is, observing what he is seeing. Cinematographers and writers often have opportunities to see what few people can see. Even the best wildlife researchers, tied as they are to their own special species and specific field sites, seldom glimpse as much firsthand as has John Aitchison. His job is to help us see it with him, and he takes the task seriously and he delivers, solidly.

What I most like about Aitchison’s approach is that, implicitly, he views the living world as sacred. He ventures out as though he is stepping into a cathedral of planetary proportions—which indeed he is. “I can think of little worse than coming here to film bears and having to shoot one instead,” he writes, “but it is a possibility we have to face because they are formidable animals.” Two things here: he forebears (no pun intended) twice in the same sentence. Usually, guns change the balance of power between humans and the Living World, but not in Aitchison’s mind; he hates the idea. Second, he calls the bears “formidable,” which in itself is restrained. A polar bear is in fact very dangerous to an unarmed human. The only thing more dangerous—is an armed human.

This book has few pretentions. We are merely treated to a view of the world at a special point in history. Ours is the time when we remain on Earth in the company of the great creatures: wolves, whales, falcons—. We can still look overhead to see scarves of geese flowing along ancient annual migration routes in the skies. Great fishes still swim beneath the sea, and penguins—perhaps the strangest birds in all the world—continue to weave themselves through the sea surface and plunge into swarms of krill.

We have changed the world greatly, and in diminishing the living world we have diminished ourselves. “It is impossible to travel widely,” Aitchison ventures, “without seeing that many wild animals are struggling.”

Yet these are not pages of doom. They reflect the energies with which all life around us strives to stay alive—and beautifully so.

From Chapter 2: Hunting with Wolves

Yellowstone is the only place in the United States where bison have lived continuously since prehistoric times, but by 1903 there were just twenty-three of them left in the park and they were not breeding successfully. The continent’s once vast herds had already been shot to oblivion. A few captive survivors were brought to join the small wild herd here and they made a crucial difference. Since then Yellowstone’s bison have slowly recovered.

The wolves had an even harder time. There were once more than a million grey wolves in North America and they killed animals from the settlers’ herds as readily as they hunted elk or bison. Killing wolves to protect cattle was seen as a matter of pride and necessity for ranchers and the Government. Even living in a National Park was no protection. When the Secretary of the Interior protected most of the park’s animals from hunting, in 1883, the regulations did not apply to wolves and everyone shot them, including the Army. The last two wolves in Yellowstone were killed in 1926 and, with their main predators gone, the park’s elk boomed. They overgrazed the plants, suppressing other herbivores, such as beavers. To redress the balance and amid great controversy, in 1995 and 1996 a Government agency brought thirty-one wolves here from Canada and released them in the Lamar Valley, close to Druid Peak.

Our journey takes us past this mountain, which gave its name to the first pack of wolves to live in its shadow in seventy years. The Druid Peak wolves thrived here, among the naïve herds of elk. In time the elk numbers started to fall, of course, but there are still plenty here and this morning we can see their tracks in the snow, as though they have been writing their stories on a page: stories about their search for food and shelter during the night, about their urge to seek safety with others and sometimes even the story of their death. All the valley’s recent history is laid out for anyone to read, until the next snowfall wipes it clean. Most of the female elk and their calves are high on the hillside, digging with their front feet to expose sparse dry grasses. Perhaps they feel safer up there, where the snow is not too deep to run away. Even so they are barely scratching a living, becoming weaker every day and a little easier to catch. By the end of the winter some of them will have consumed the marrow in their own bones.

A raven passes overhead, flying high and direct. We follow its line across the river and it leads us to the wolves. The whole Druid pack is gathered in a clearing on the forest edge. We watch them intently, studying how each wolf fits into its extended family. Some are curled up asleep. One stands off to the side, leaping again and again, trying to bite a dangling pinecone from a tree. When it succeeds it immediately drops the cone and starts to chase its own tail. A dark wolf, clearly subordinate, greets the palest one, wagging his tail and squirming as low as he can, to lick her muzzle. This is how the hierarchy works, each pack member is in its own place below the pale wolf and her mate: the alpha pair. It’s fascinating to see this played out, but there are sixteen wolves to keep track of and there’s half a mile between us. To the naked eye they are not much more than dots and, in order to film them closer, we will need to find and follow them every day. In just a few hours wolves can travel enormous distances and for two thirds of our time here it is going to be dark.

*

Every year since the wolves were reintroduced, scientists have fitted some of them with collars which produce radio signals. Rick McIntyre is a Biological Technician for the Yellowstone Wolf Project. His job is to monitor the radio-collars in this part of the park and record as much as he can about the behaviour of the Druid Peak wolves, and several other packs too. We find him by the roadside, surrounded by a large group of people with telescopes on tripods. Rick is staring through his own telescope and patiently describing exactly where the wolves are, using rocks and trees as landmarks, so the visitors can find them too. He raises an aerial, turns it this way and that, while listening for the collars’ beeps, then changes the orientation and listens again. He speaks into a pocket recorder:

“569 is there right now and so is 480. 302 is out of sight somewhere to the right.”

On their way here, other people have seen different wolves. Like Rick’s, their descriptions are a mixture of numbers and nicknames. Nathan and I meet Laurie, a visitor who has spent years watching Yellowstone’s wolves. She explains to us how to tell the sixteen Druid wolves apart. Eight of them are black and eight are “grey” (actually a sandy and dark mixture, quite like a pale German Shepherd dog). Four are collared and known by numbers: 569F is the beautiful alpha female, so pale she is almost white, her mate, 480M, is the black alpha male and his brother is 302M. The other collared wolf is a younger male. Laurie says male wolves are collared more often than females because, instead of making straight for the trees, they stop to look back at the helicopter which is carrying a biologist with a dart gun. Once they are collared the scientists move the unconscious wolves to the centre of their territory and revive them together. It’s safer than waking up alone, feeling groggy, with another potentially hostile pack nearby.

Laurie carries on listing the Druids. It’s a dizzying mass of information: There are six yearlings, some with marks on their fronts and sides, like the grey bars which separate the black wolves, “Light-bar” and “Dull-bar.” Most of these yearlings are the alpha pair’s pups from two summers ago, which the whole pack helped to raise. They are all female. There are seven younger wolves too, the most recent pups, now fully-grown. None of them have names and they are hard to tell apart. Laurie recognises this group by the ruffs on their necks, which look like raised hackles, and because they behave like pups too: it was probably one of these we saw jumping for the pinecone. Identifying the wolves is the vital first stage in predicting what they might do. It could make all the difference between being in the right place or the wrong one when it comes to filming. There’s a lot to learn and we have a month in which to do it.

The visitors have come from a wide range of countries. Many have seen and been captivated by these wolves on television or on the Internet: the Druids are the most famous wolf pack in the world and the most watched. 302 is everyone’s favourite. He was sometimes called Casanova when he was young, for the daring liaisons he had with females from other packs, under the noses of their own males. He even has his own blog, run by someone in Florida. Since the demise of the Plains Indian tribes, a century or more ago, people have rarely connected so strongly with wild wolves. Such empathy is only possible because Rick, Laurie and many others, have spent an immense amount of time coming to knowing individual wolves and their stories. Rick alone has clocked up more than four thousand days. For the last four and a half years he has been here seven days a week but, when Laurie introduces us, he hides his dedication with a joke: “I once caught a cold in 1997 but I came in anyway.”

He welcomes us and explains that the pack usually moves every few days, but this year the heavy snow has kept them in the Lamar Valley for an unprecedented six weeks. Although they have often been visible from the road so far, they could decide to leave at any time.

*

There was a fight last night in one of Cooke City’s bars. Afterwards we could hear some boys from Idaho playing chicken with their huge snowmobiles on the icy main street. We’d had an early night, not to avoid the fighting, but because we had to be up at 4:30 and ready to drive into the park before first light.

Inter canem et lupum (between the dog and the wolf) meant twilight in the Roman world, when wolves were common everywhere. A dog barks as we leave town. Cooke City’s dogs must be early risers, because there is not a hint of light in the sky as we drive towards the park entrance. Dark mountains crowd close to the road: Abiathar Peak, Mount Norris and the Thunderer. There is nowhere in Yellowstone lower than the top of Britain’s highest summit and these mountains are more than twice that high. Through gaps in the trees we glimpse snow-covered prairies, where streams trickle between hummocks as smooth and white as iced cakes. How should we search for a single pack of wolves in so much space? As we near the Lamar Valley the light comes up and we stop to search for wolf-shapes moving on the snow, studying the elk closely, looking where they are looking. The elk seem relaxed and nothing moves, so we drive on and try again. In each place we listen and finally we hear the Druids howl.

America’s early settlers described wolf howls as mournful or blood-curdling, a projection of their own fears onto the sounds which wolves make to keep their packs together and their neighbours away. For a wolf pack to thrive they need the exclusive use of a large territory with plenty of prey. Advertising their numbers by howling together is a show of strength. To us, without any livestock to lose, the sound is beautiful, like a choir singing in close-harmony. Each wolf joins in with the others at a different pitch, to give the impression of a stronger pack: one to leave alone. Their voices carry astonishingly far, echoing from the face of the Thunderer and sustained by the distance, long after they have lowered their muzzles. It is wild music I do not want to end.

*

We find Rick at a place called Round Prairie, checking the signals from the radio collars. He says there are wolves close by, somewhere in the trees, so we set up the camera and wait, hoping they will show themselves. There are seven bull elk in the meadow: enormous deer, weighing perhaps half a tonne each, with pointed antlers, spanning more than a metre on either side. They seem very wary, eyeing the shadows. Perhaps the wolves are just checking them, staying out of sight rather than facing one down, as Rick says they sometimes do, to test its resolve, daring it to make the first move.

The signals fade. The wolves are moving away down the valley, hidden by the trees. We follow along the road until they appear on the far side of the river, trotting in a line: first the alpha pair then 302 and a few of the others. While the adults have been away another wolf has used their absence to introduce himself to the younger pack members. He’s a lone grey male. The yearling females are particularly pleased to see him and there is a great deal of sniffing and tail wagging. The lone male knows he is taking a risk and when he’s spotted by the returning brothers, 480 and 302, he immediately break into a run. They give chase but the alpha male soon stops. 302 runs on. He has more to lose because he’ll be able to mate with the young females in his pack, as long as he sees off the competition. The interloper runs in a loop, knowing his pursuer will follow his trail by scent rather than cutting the corner, which allows him to check whether he is still being followed. He is and 302 chases him into the distance.